One obvious way to inject more value into a task is to reward yourself for completing it.

Research shows that this doesn’t work for most people (but maybe it does for you). The reason seems to be that most people normally go and get what they want if they can. In order to turn something that you can always have into a reward, you would have to suppress this. Instead of rewarding yourself, you end up punishing yourself.

To use your example, you are not bribing yourself with Pinkberry frozen yogurt at all; you know that you can have your Pinkberry frozen yogurt whenever you want. You are actually denying yourself the Pinkberry frozen yogurt until you’ve finished the task. After the completion of the task you just restore normality. Every time your subconscious asks you, “I want Pinkberry frozen yogurt, why am I doing this to myself?”, your conscious comes back saying “Because I need to motivate myself to do this task I hate.” You begin to associate the task with Pinkberry-frozen-yoghurt deprivation and you start hating the task even more. Motivation goes down.

Furthermore, there’s the side-effect of having Pinkberry frozen yogurt at a time when you would normally not actually want it...

Awesome article as always. I really like your recent high-quality posts, Luke.

A few additional notes.

1) I was already more or less aware of this research through the language learning community, mostly the Japanese one. For example, Khatzumoto has been advocating this for some time now, see this article for an explanation or this trilogy in 9 parts for practical advice how to fix it. (Because LW isn't really about learning languages, I'll just leave it at this.)

These techniques try not to fix your own attitude (like, giving you lower Impulsiveness, changing the Value you assign or affecting your optimism), but instead change the learning strategies in such a way that they work regardless of these problems. So instead of learning how to tackle larger goals, they instead choose really tiny ones. Khatz for example strongly advocates timeboxes of 90 seconds or less, or changing the learning material to intrinsically fun stuff (manga instead of textbooks). This is something that the traditional procrastination literature doesn't really address very much. It has helped me a lot, in addition to all the approaches you already described.

2) I strongly agree with this model, but I'm not sure ...

What a wonderful post!

I considered the benefits of meditation as a procrastination control technique and you will find it in the notes section of the book. I have practiced mindfulness meditation but no longer keep up with it. Though the mindfulness part does give you an option to reduce the power of temptations, you are quite right that it also can expand to eliminate value in general (nihilism). However, the reason I rejected it as viable solution is that it takes so long to master and this is the exact type of discipline that procrastinators will put off aquiring. Good in theory but of little practical value because people won't take the time to put it into practice. Maybe this is why the Pali Cannon calls procrastination "moral defilement."

As for self-rewards, I did debate whether to include them. In my original doctoral dissertation, I wrote this "However, it is uncertain whether rewards will be as effective when self-administered. Ainslie (1992) indicates that self-rewards are very susceptible to corruption, where the rules are bent to the extent that they are no longer effective. I suspect that the use of self-rewards will be negatively correlated with procra...

In general, this post looks useful and well researched, so upvoted. This is my only problem with it:

Another method is to make failure really painful.

For me personally, this is a really bad idea because it'll kick me into pain motivation mode and uselessly cause me more stress (decreasing my effectiveness.) You've clearly read much more then me on the subject, and so this may work for some people, but I think that it has a chance to significantly backfire for others.

I've had this page in a tab in my browser for days intending to read it, and still haven't. Seriously.

It's nice to know my acrasia has a sense of humour.

Since there is usually little you can do about the delay of a task's reward

It seems like delay is a factor that can be manipulated in some ways. For example, one might set a sub-goal of having the term paper written in an acceptable draft form halfway through the semester, to be reviewed by a teacher or peer. This would be processed differently from the end goal of having the final version ready at the end of the semester.

Thank you so very very much for hosting pdfs of the journal articles you cite. Tracking those down between 20 different academic paywalls would have been very painful for me.

And they even all have beautiful names like Zimmerman-Becoming-a-self-regulated-learner.pdf, rather than the 7168761.pdf that you often get when downloading an academic paper.

I wish I could vote this most awesome article up multiple times.

Note that there's an Anti-Akrasia technique in here waiting to happen: If you can increase the delay of a rewarding but unproductive task that otherwise has no delay at all then you reduce your motivation to do it.

Internet browsing comes to mind. I think the XKCD author has done something to this effect (check out the comic's comment here: http://xkcd.com/862/). To quip, he wrote a script that made his computer freeze for thirty seconds every time he opened unwanted material.

When Richard Stallman wants to view a web page, he sends the URL in an email to a server operated by him or one of his friends, and the server mails him back the page. He says that he does it that way "for personal reasons", and my guess is that it is an anti-akrasia measure.

Very nice review here. Any better and I would say you needn't bother buying the book. About the equation, it is indeed a simplification of the full model -- trying to balance completeness with making sure it is understandable. As the book (and for those super keen, Temporal Motivation Theory described in my Academy of Management Review article "Integrating Theories of Motivation"), we add a constant in the denomenator to prevent the entire thing sky rocketing to infinity when delay approaches zero (in joke, one of the characters has a kid named Constance in reference to this).

I think the biggest problem with procrastination is that it results from fairly rational formulae, give or take a little outdated evolved psychology. The rewards that are far in the future are intrinsically less certain as the probability of drastic change accumulates over time, especially for impulsive individuals; the rewards of studying are many years into the future, and the utility of those rewards is very, very low on the biological scale of things, for the people living in rich countries.

As far as biology is concerned, human is a system with 1 ultimate goal: reproduction. Other behaviours (e.g. pursuit of status) are only means to an end. Studying in the developed countries, in particular is an extremely ineffective form of pursuit of status which is particularly unlikely to improve reproductive success, and is likely to decrease it.

It is bloody hard to use rationality to fight for the behaviours (studying) which much of your hardware has rightfully and rationally deemed irrational and not worth the time expenditure.

The conscious 'mind' is like a naive figurehead that gets fooled by everyone and everything, which is good for a honest face while repeating the lies (it rep...

Edit: Apparently not actually pseudomath, only looks like it, due to undefined scale and meaning of parameters. Although still contains a simplification made for rhetorical reasons that makes the formula wrong (see footnote 6).

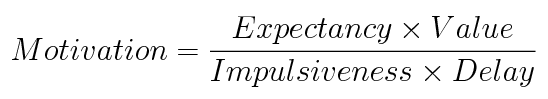

This leaves us with "the procrastination equation":

I don't believe such pseudomath is a good way of evoking the relevant intuitions, given the downside of being meaningless. Isn't it strictly better to just say is as follows?

These are the factors that influence motivation the most:

- Expectancy and Value promote motivation.

- Impulsiveness and Delay decrease motivation.

Using the equation allowed Steel (2010a) to predict fairly accurately the behavior of students in an online course at the University of Minnesota.

Vladimir,

I am using the equation rhetorically, on purpose. The footnote given immediately after the equation explains that the version in this post is pseudomath, and lists the paper that gives the true equation (and its measurement units) and argues for its validity. I even went to the trouble of uploading a PDF of that paper (and 30+ others) so you can read it yourself:

Steel & Konig (2006). Integrating theories of motivation. Academy of Management Review, 31(4): 889-913.

I do not argue for the truth of any of my claims in this article. That would take a book, not an article. I just list the advice, and leave the arguments about truth and conceptual validity for the footnotes and the references, which I have provided, with great effort.

Isn't the equation just standard expected utility maximization, with hyperbolic discounting? (That is, if Luke hadn't removed the additive constant in the denominator that was in the original equation.)

Motivation = (Expectancy*Value)/(Impulsiveness*Delay)

If this equation is right, then Impulsiveness appears to be a meaningless quantity. A more impulsive person would be less motivated to perform a task, but also would be less motivated to perform competing tasks. Changing Impulsiveness scales all Motivations equally, preserving the same structure of relative Motivation.

In my personal experience, the most common cause of procrastination and lack of willpower is open-ended tasks.

Examples:

At school I would complete any short-answer or multiple choice homework in class or as soon as I got home,

but I would procrastinate over and often fail to complete any homework which involved writing essays, and

the more open-ended the essay question the more I would procrastinate over it. Similarly, if I was asked to

show workings out for my calculations I would refuse to do it, whereas I would usually comply when I was

given equa...

Actually, the Expectancy (probability of success) component is not that simple: you don't just maximize it to maximize motivation. As Robert Sapolsky shows in "The Uniqueness of Humans" (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hrCVu25wQ5s), motivation is proportional to the dopamin spike you get when you start to consider performing a task, and the dopamin spike is highest the closer your estimated probability of success is to (something like) 50%! The amount of dopamin produced when you consider starting a task that you have 25% or 75% chances of succee...

"we irrationally find present costs more salient than future costs"

Present Bias is not always irrational!

it can be rationalized (as in, "find rational cause" not "make up excuse") as hedging against uncertainty. the future is never certain. our predictions about the future aren't even probable. if you save your money instead of spending it, you might lose it all to madoff. if you don't use that giftcard to some restaurant, your tastes might change and it won't be worth anything.

in fact, Geometric Discouting maximizes average (...

If the task you're avoiding is boring, try to make it more difficult, right up to the point where the difficulty level matches your current skill, and you achieve "flow."21 This is what the state troopers of Super Troopers did: they devised strange games and challenges to make their boring job passable. Myrtle Young made her boring job at a potato chip factory more interesting and challenging by looking for potato chips that resembled celebrities and pulling them off the conveyor belts.

What do you do if the task is both boring and extremely difficult, rather than boring and easy?

Here is the procrastination equation image (since it's currently broken in the main text).

And the same equation in math:

Any number of interventions can help with a task you're procrastinating on. But if you'd prefer to start with an understanding of procrastination as a phenomenon, see my "The Last Word on Procrastination: An integration of ego-depletion theory, construal-level theory, and the irreversibility of writing."

I really like parts of this, but other parts -- like "focus on doing what you love" and "increase your expectancy of success" -- strike me as banal or vacuous. Note that I have a very biased view of this stuff, as will be clear from my recent anti-akrasia post on LessWrong: Anti-akrasia tool: like stickK.com for data nerds

So it won't be surprising that the part of this I really love, and what I think is the part that really matters, is commitment devices and setting goals that are measurable, realistic, and time-anchored (so-called SMAR...

One way to keep the "Delay" high is to not have an external deadline or not commit to your own deadline. This is a real killer for me: without a proper deadline tasks are always too early or too late. When I'm "too early", the task can be started but doesn't get anywhere. Then, when I feel it's "too late", low expectations take over. Up till now I've used to think that the arbitrariness of setting your own deadline kills it (since it's arbitrary, it can be reset on a whim). Now I see that thinking carefully about a deadline can reduce the arbitrariness.

Drink lots of water. Stop eating anything that contains wheat and other grains.

I don't think that either of these two has much evidence going for it.

Do short but intense exercise once a week.

Once a week is not often enough. The endorphins from exercise wear off fast so to sustain high energy levels I require a short burst of intense exercise is required every few hours with a longer run at least once a day.

So this may be other-optimizing if you heed my anecdote, but contemplating my own swiftly approaching death (an idea I take from Stoicism) helps my procrastination. In the context of this article, I think it works because it decreases my impulsiveness by forcing me to view my time as a finite resource, thus reducing some (not all) hyperbolic discounting of rewards. When I get up in the morning, if I say to myself something like "I probably have less than 20,000 days left to live, and this is one of those days," I find it easier to do tasks that m...

Great article. One statement that really caught my eye was the reccomendation to not clutter your life. That's exactly how I would describe my life at this point. Cluttered. If anybody was any advice on how to declutter and refocus your life that would be greatly appreciated.

I thought it was comical that I clicked the O*NET link and spent a good 10min or so on that site just to come back to the next heading which was "Handling Impulsiveness"

Well played, author! Thanks for the sequence!

These are awesome ideas and techniques, thanks for compiling them Luke! I personally work with a category of people who have a hard time implementing even these - they get into meta depression/hopelessness/angst and are unable to follow through on basic positive reinforcement like smiling after completing a task - it causes them to think about all of the other tasks they haven't done and they feel bad.

For people stuck in that category, I recommend Internal Family Systems counseling with a good facilitator and/or Landmark. The problem is usually some s...

This article is very useful and well researched. However, I do have a question regarding:

De-clutter your life, because clutter is cognitively exhausting for your brain to process all day long.

Is this true? I've never actually heard of it before, but I'd like to see the research on it. (I did read through the sources, but I could have missed it) It sounds plausible and would have some interesting implications if it is. So people who have really messy desks are just making life harder for themselves?

Interesting discussion and well put. It would be relevant here to mention though that one of the commonest tie ins between impulsivity and procrastination is ADHD. It is something that is well worth considering when anyone is faced with industrial strength procrastination & impulsivity problems - as it is usually missed in Adults. Just as modafinil can be helpful- so can the psychostimulants. They are also much older, better understood drugs with a very clearly understood safety profile.

Equally it is worth noticing on the "value " end of the equation- that sometimes we procrastinate because we are subconsciously aware that what we are proposing to do is not the most important thing we could/should be doing.

Temporal construal theory is known on LW as near/far thinking - you may want to mention/link that in fn 5.

Thought you might like to see David Hume outlining the basics of construal theory about 300 years earlier. Here he is reflecting on how the nearby and concrete always seems to supersede the long-term and abstract:

“In reflecting on any action which I am to perform a twelvemonth hence, I always resolve to prefer the greater good, whether at that time it will be more contiguous or remote; nor does any difference in that particular make a difference in my present intentions and resolutions. My distance from the final determination makes all those minute differences vanish, nor am I affected by anything but the general and more discernible qualities of good and evil. But on my nearer approach, those circumstances which I at first overlooked begin to appear, and have an influence on my conduct and affections. A new inclination to the present good springs up, and makes it difficult for me to adhere inflexibly to my first purpose and resolution. This natural infirmity I may very much regret, and I may endeavour, by all possible means, to free myself from it.”

As an ADHD person for whom "reduce impulsiveness" is about as practical a goal as "learn telekinesis", reducing delay is actually super easy. Did you know people feel good about completing tasks and achieving goals? All you have to do to have a REALLY short delay between starting the task and an expected reward is explicitly, in your own mind, define a sufficiently small sub-task as A Goal. Then the next one, you don't even need breaks in-between if it goes well - even if what you're doing is as inherently meaningless as, I dunno, filling in an excel table...

I've finally learned the key to hacking the impulse part of the equation. Distancing, minimization and distraction are useful. As is self-deception, or perhaps it is enlightened reason: that the desire for a thing is pleasure and reward in itself, there is no need to satiate a craving, just as there is no need to avert a negative feeling or harmful stimuli.

I've personally found HabitRPG.com helpful. I'd recommend setting an 'eat that frog' daily which costs you a lot of health if I don't complete it. There's an effective altruists party that anyone's welcome to join: https://www.facebook.com/groups/560438844048626/

"but most people have the most energy during a period starting a few hours after they wake up and lasting 4 hours"

There's no way this is true. Mentally, you're much slower in the morning than the evening. In fact, for optimal intellectual functioning, your body temperature has to be at its highest, not at its lowest and thus you're most productive in the last 4 hours before going to bed rather than the first after rising. I've had other programmer colleagues confirm this to me: how they feel twice as productive at the end of the day than at the b...

Well I just had an interesting opportunity to try out some of these techniques, because I was supposed to be working on a project and decided to "take a break" by reading Less Wrong. These techniques do seem to be helping.

I am a little bit leary of the first section, about trying to increase your own optimism. In general, I'm a little suspicious of trying to get myself to feel something that may not be justified. Fortunately, in my own case, I do know that I am perfectly capable of completing my current goal. I've done harder things.

For your information, Myrtle Young https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EY3Lw_-bj5U is now a broken link. (sad. Sounds funny)

Apart from that, thanks. Interesting article. At least because I had no idea so much research where done on those subjects.

procrastination, there are no limits to what you can accomplish when you are supposed to be doing something else. Then again, those other things just add to a list of ongoing commitments that lead to great procrastination and the stress that comes with it which could be surmounted by just getting things done.

May I just point out some things about the equation

part of the expected utility

No, it's not that central to that at all. It's grounded in that, no the other way around. Also, it's certainly not mainstream. It's very new. Not wrong, just not very well scrutinised.

All good in theory but how would you apply this equation to procrastinating on something like exam revision?

- Increase your expectancy of success.

This isn't relevant in most cases of procrastination. I already know I can successfully revise for exams, I've done it before, it's just too boring, so I don't feel like doing it. It's the same with say, washing the dishes - I know I can do it, but it's just boring. And revision requires a lot more mental effort than washing the dishes.

- Increase the task's value (make it more pleasant and rewarding).

Flow -...

FWIW, this is one of my favourite articles. I can't say how much it would help everyone -- I think I read it when I was just at the right point to think about procrastination seriously. But I found the analytical breakdown into components incredibly helpful way to think about it (and I love the sniper rifle joke).

I get the feeling this equation would be a bit more useful if Passion was a more prominent factor in it. As it is, it's hidden in the Value variable.

It could be a bit misleading. For instance, I automatically was thinking about monetary value and usefulness and such, while completely forgetting to include the Passion factor. If the Passion isn't weighted heavily in the equation, motivation might turn out to be low regardless of how high the "Value" (besides passion) might be.

Maybe I should work on reducing the "value" part of the equation for distracting activities. (For example, reading negative reviews of "The Secret" on Amazon)

I suppose there were studies of placebo effect - which I haven't read - but just a thought: Could it be that placebo treatment induces the placebo effect not only by making the patients believe they perceive a positive effect, but by actually changing their behavior? Of course it depends on the treated problem, but placebo surely raises the patients' expectation of getting better and thus raises their motivation to help themselves (according to the procrastination equation).

Do you know about any research that relates this to the "anti-" case of this? That is, how expectancy, "value", delay and impulsiveness affects evaluation of risk and potential future punishment and how it affects one's behavior under that evaluation?

I wonder how this can be applied to action one might perform that is shunned by society, such as crime. Perhaps it's basically the same case (we incorporate the risk and adverse effects to the value and expectancy), but it seems that there are two stages in such cases which make it more com...

A great post - I love the quantity and quality of information you have squeezed into such a compact article.

I will be seeing how the recommendations work for me over the next week or so.

Thanks!

Which Bible translation is the St. Paul quote at the top from? The first sentence matches the Phillips translation (that I just learned about) but the rest doesn't.

I ask because (in the context of akrasia) I've seen that quote a lot, but never in the very modern, common-language phrasing you've given. I checked the more contemporary translations and couldn't find it in those either.

I would reference the behavioral economics on loss aversion to up the value of a task. Rather than focusing on increasing the positive value via upping the reward, I would increase the negative value of inaction. Personally, I've taken to fining myself for not getting things done on time (all the money goes into a jar next to my desk, which goes to charity at the end of the month). This system has worked wonders - it even has power to control my less rational selves (e.g. drunk self and just-woke-up self)

I'm curious about the equation you mentioned. Has it actually been proven that motivation is directly proportional to expectancy and value but inversely proportional to time and impulsiveness? I mean in humans rather than in ideal utility maximisers (although I don't think ideal utility maximisers are known for their impulsiveness so I'm not even sure if it applies to them).

I didn't even know it was possible to rigorously measure motivation and impulsiveness.

Impressive! (though the underspecified math did bother me a bit.) I wonder how long did it take you to write?

Could you state the actual equation? It doesn't sound like you've simplified it much; its current form bugs me. Also I assume there must be some constant of proportionality in there, since it seems unlikely the dimensions will work out otherwise... unless "impulsiveness" is chosen to have dimensions so that it does?

Edit: For that matter, how are we measuring motivation in this context? What does the output actually mean?

Very nice review here. Any better and I would say you needn't bother buying the book. About the equation, it is indeed a simplification of the full model -- trying to balance completeness with making sure it is understandable. As the book (and for those super keen, Temporal Motivation Theory described in my Academy of Management Review article "Integrating Theories of Motivation"), we add a constant in the denomenator to prevent the entire thing sky rocketing to infinity when delay approaches zero (in joke, one of the characters has a kid named Constance in reference to this).

I'm going to have to sit down and read this whole essay and take notes one of these days, when I have more time.

Having just spent dozens of hours reading academic and popular literature on procrastination to write this post, I can tell you that I will never laugh at this style of joke again. :(

Part of the sequence: The Science of Winning at Life

- Saint Paul (Romans 7:15)

Once you're trained in BayesCraft, it may be tempting to tackle classic problems "from scratch" with your new Rationality Powers. But often, it's more effective to do a bit of scholarship first and at least start from the state of our scientific knowledge on the subject.

Today, I want to tackle procrastination by summarizing what we know about it, and how to overcome it.

Let me begin with three character vignettes...

Eddie attended the sales seminar, read all the books, and repeated the self-affirmations in the mirror this morning. But he has yet to make his first sale. Rejection after rejection has demoralized him. He organizes his desk, surfs the internet, and puts off his cold calls until potential clients are leaving for the day.

Three blocks away, Valerie stares at a blank document in Microsoft Word. Her essay assignment on municipal politics, due tomorrow, is mind-numbingly dull. She decides she needs a break, texts some friends, watches a show, and finds herself even less motivated to write the paper than before. At 10pm she dives in, but the result reflects the time she put into it: it's terrible.

In the next apartment down, Tom is ahead of the game. He got his visa, bought his plane tickets, and booked time off for his vacation to the Dominican Republic. He still needs to reserve a hotel room, but that can be done anytime. Tom keeps pushing the task forward a week as he has more urgent things to do, and then forgets about it altogether. As he's packing, he remembers to book the room, but by now there are none left by the beach. When he arrives, he finds his room is 10 blocks from the beach and decorated with dead mosquitos.

Eddie, Valerie, and Tom are all procrastinators, but in different ways.1

Eddie's problem is low expectancy. By now, he expects only failure. Eddie has low expectancy of success from making his next round of cold calls. Results from 39 procrastination studies show that low expectancy is a major cause of procrastination.2 You doubt your ability to follow through with the diet. You don't expect to get the job. You really should be going out and meeting girls and learning to flirt better, but you expect only rejection now, so you procrastinate. You have learned to be helpless.

Valerie's problem is that her task has low value for her. We all put off what we dislike.3 It's easy to meet up with your friends for drinks or start playing a videogame; not so easy to start doing your taxes. This point may be obvious, but it's nice to see it confirmed in over a dozen scientific studies. We put off things we don't like to do.

But the strongest predictor of procrastination is Tom's problem: impulsiveness. It would have been easy for Tom to book the hotel in advance, but he kept getting distracted by more urgent or interesting things, and didn't remember to book the hotel until the last minute, which left him with a poor selection of rooms. Dozens of studies have shown that procrastination is closely tied to impulsiveness.4

Impulsiveness fits into a broader component of procrastination: time. An event's impact on our decisions decreases as its temporal distance from us increases.5 We are less motivated by delayed rewards than by immediate rewards, and the more impulsive you are, the more your motivation is affected by such delays.

Expectancy, value, delay, and impulsiveness are the four major components of procrastination. Piers Steel, a leading researcher on procrastination, explains:

The Procrastination Equation

This leaves us with "the procrastination equation":

Though we are always learning more, the procrastination equation accounts for every major finding on procrastination, and draws upon our best current theories of motivation.6

Increase the size of a task's reward (including both the pleasantness of doing the task and the value of its after-effects), and your motivation goes up. Increase the perceived odds of getting the reward, and your motivation also goes up.

You might have noticed that this part of the equation is one of the basic equations of the expected utility theory at the heart of economics. But one of the major criticisms of standard economic theory was that it did not account for time. For example, in 1991 George Akerlof pointed out that we irrationally find present costs more salient than future costs. This led to the flowering of behavioral economics, which integrates time (among other things).

Hence the denominator, which covers the effect of time on our motivation to do a task. The longer the delay before we reap a task's reward, the less motivated we are to do it. And the negative effect of this delay on our motivation is amplified by our level of impulsiveness. For highly impulsive people, delays do even greater damage to their motivation.

The Procrastination Equation in Action

As an example, consider the college student who must write a term paper.7 Unfortunately for her, colleges have created a perfect storm of procrastination components. First, though the value of the paper for her grades may be high, the more immediate value is very low, assuming she dreads writing papers as much as most college students do.8 Moreover, her expectancy is probably low. Measuring performance is hard, and any essay re-marked by another professor may get a very different grade: a B+ essay will get an A+ if she's lucky, or a C+ if she's unlucky.9 There is also a large delay, since the paper is due at the end of the semester. If our college student has an impulsive personality, the negative effect of this delay on her motivation to write the paper is greatly amplified. Writing a term paper is grueling (low value), the results are uncertain (low expectancy), and the deadline is far away (high delay).

But there's more. College dorms, and college campuses in general, might be the most distracting places on earth. There are always pleasures to be had (campus clubs, parties, relationships, games, events, alcohol) that are reliable, immediate, and intense. No wonder that the task of writing a term paper can't compete. These potent distractions amplify the negative effect of the delay in the task's reward and the negative effect of the student's level of impulsiveness.

How to Beat Procrastination

Although much is known about the neurobiology behind procrastination, I won't cover that subject here.10 Instead, let's jump right to the solutions to our procrastination problem.

Once you know the procrastination equation, our general strategy is obvious. Since there is usually little you can do about the delay of a task's reward, we'll focus on the three terms of the procrastination equation over which we have some control. To beat procrastination, we need to:

You might think these things are out of your control, but researchers have found several useful methods for achieving each of them.

Most of the advice below is taken from the best book on procrastination available, Piers Steel's The Procrastination Equation, which explains these methods and others in more detail.

Optimizing Optimism

If you don't think you can succeed, you'll have little motivation to do the task that needs doing. You've probably heard the advice to "Be positive!" But how? So far, researchers have identified three major techniques for increasing optimism: Success Spirals, Vicarious Victory, and Mental Contrasting.

Success Spirals

One way to build your optimism for success is to make use of success spirals.11 When you achieve one challenging goal after another, your obviously gain confidence in your ability to succeed. So: give yourself a series of meaningful, challenging but achievable goals, and then achieve them! Set yourself up for success by doing things you know you can succeed at, again and again, to keep your confidence high.

Steel recommends that for starters, "it is often best to have process or learning goals rather than product or outcome goals. That is, the goals are acquiring or refining new skills or steps (the process) rather than winning or getting the highest score (the product)."12

Wilderness classes and adventure education (rafting, rock-climbing, camping, etc.) are excellent for this kind of thing.13 Learn a new skill, be it cooking or karate. Volunteer for more responsibilities at work or in your community. Push a favorite hobby to the next level. The key is to achieve one goal after another and pay attention to your successes.14 Your brain will reward you with increased expectancy for success, and therefore a better ability to beat procrastination.

Vicarious Victory

Pessimism and optimism are both contagious.15 Wherever you are, you probably have access to community groups that are great for fostering positivity: Toastmasters, Rotary, Elks, Shriners, and other local groups. I recommend you visit 5-10 such groups in your area and join the best one.

You can also boost your optimism by watching inspirational movies, reading inspirational biographies, and listening to motivational speakers.

Mental Contrasting

Many popular self-help books encourage creative visualization, the practice of regularly and vividly imagining what you want to achieve: a car, a career, an achievement. Surprisingly, research shows this method can actually drain your motivation.16

Unless, that is, you add a second crucial step: mental contrasting. After imagining what you want to achieve, mentally contrast that with where you are now. Visualize your old, rusty car and your small paycheck. This presents your current situation as an obstacle to be overcome to achieve your dreams, and jumpstarts planning and effort.17

Guarding Against Too Much Optimism

Finally, I should note that too much optimism can also be a problem,18 though this is less common. For example, too much optimism about how long a task will take may cause you to put it off until the last minute, which turns out to be too late. Something like Rhonda Byrne's The Secret may be too optimistic.

How can you guard against too much optimism? Plan for the worst but hope for the best.19 Pay attention to how you procrastinate, make backup plans for failure, but then use the methods in this article to succeed as much as possible.

Increasing Value

It's hard to be motivated to do something that doesn't have much value to us - or worse, is downright unpleasant. The good news is that value is to some degree constructed and relative. The malleability of value is a well-studied area called psychophysics,20 and researchers have some advice for how we can inject value into necessary tasks.

Flow

If the task you're avoiding is boring, try to make it more difficult, right up to the point where the difficulty level matches your current skill, and you achieve "flow."21 This is what the state troopers of Super Troopers did: they devised strange games and challenges to make their boring job passable. Myrtle Young made her boring job at a potato chip factory more interesting and challenging by looking for potato chips that resembled celebrities and pulling them off the conveyor belts.

Meaning

It also helps to make sure tasks are connected to something you care about for its own sake,22 at least through a chain: you read the book so you can pass the test so you can get the grade so you can get the job you want and have a fulfilling career. Breaking the chain leaves a task feeling meaningless.

Energy

Obviously, tasks are harder when you don't have much energy.23 Tackle tasks when you are most alert. This depends on your circadian rhythm,24 but most people have the most energy during a period starting a few hours after they wake up and lasting 4 hours.25 Also, make sure to get enough sleep and exercise regularly.26

Other things that have worked for many people are:

Rewards

One obvious way to inject more value into a task is to reward yourself for completing it.27

Also, mix bitter medicine with sweet honey. Pair a long-term interest with a short-term pleasure.28 Find a workout partner whose company you enjoy. Treat yourself to a specialty coffee when doing your taxes. I bribe myself with Pinkberry frozen yogurt to do things I hate doing.

Passion

Of course, the most powerful way to increase the value of a task is to focus on doing what you love wherever possible. It doesn't take much extra motivation for me to research meta-ethics or write summaries of scientific self-help: that is what I love to do. Some people who love playing video games have made careers out of it. To figure out which career might be full of tasks that you love to do, taking a RIASEC personality test might help. In the USA, O*NET can help you find jobs that are in-demand and fit your personality.

Handling Impulsiveness

Impulsiveness is, on average, the biggest factor in procrastination. Here are two of Steel's (2010a) methods for dealing with impulsiveness.

Commit Now

Ulysses did not make it past the beautiful singing Sirens with willpower. Rather, he knew his weaknesses and so he committed in advance to sail past them: he literally tied himself to his ship's mast. Several forms of precommitment are useful in handling impulsiveness.29

One method is to "throw away the key": Close off tempting alternatives. Many people see a productivity boost when they decide not to allow a TV in their home; I haven't owned one in years. But now, TV and more is available on the internet. To block that, you might need a tool like RescueTime. Or, unplug your router when you've got work to do.

Another method is to make failure really painful. The website stickK lets you set aside money you will lose if you don't meet your goal, and ensures that you have an outside referee to decide whether your met your goal or not. To "up the ante," set things up so that your money will go to an organization you hate if you fail. And have your chosen referee agree to post the details of your donation to Facebook if you don't meet your goal.

Set Goals

Hundreds of books stress SMART goals: goals that are Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Realistic, and Time-Anchored.30 Is this recommendation backed by good research? Not quite. First, notice that Attainable is redundant with Realistic, and Specific is Redundant with Measurable and Time-Anchored. Second, important concepts are missing. Above, we emphasized the importance of goals that are challenging (and thus, lead to "flow") and meaningful (connected to things you desire for their own sake).

It's also important to break up goals into lots of smaller subgoals which, by themselves, are easier to achieve and have more immediate deadlines. Typically, daily goals are frequent enough, but it can also help to set an immediate goal to break you through the "getting started" threshold. Your first goal can be "Write the email to the producer," and your next goal can be the daily goal. Once that first, 5-minute task has been completed, you'll probably already be on your way to the larger daily goal, even if it takes 30 minutes or 2 hours.31

Also: Are your goals measuring inputs or outputs? Is your goal to spend 30 minutes on X or is it to produce final product X? Try it different ways for different tasks, and see what works for you.

Because we are creatures of habit, it helps to get into a routine.32 For example: Exercise at the same time, every day.

Conclusion

So there you have it. To beat procrastination, you need to increase your motivation to do each task on which you are tempted to procrastinate. To do that, you can (1) optimize your optimism for success on the task, (2) make the task more pleasant, and (3) take steps to overcome your impulsiveness. And to do each of those things, use the specific methods explained above (set goals, pre-commit, make use of success spirals, etc.).

A warning: Don't try to be perfect. Don't try to completely eliminate procrastination. Be real. Overregulation will make you unhappy. You'll have to find a balance.

But now you have the tools you need. Identify which parts of the procrastination equation need the most work in your situation, and figure out which methods for dealing with that part of the problem work best for you. Then, go out there and make yourself stronger, score that job, and help save the world!

(And, read The Procrastination Equation if you want more detail than I included here.)

Next post: My Algorithm for Beating Procrastination

Previous post: Scientific Self-Help: The State of Our Knowledge

Notes

1 These are the fictional characters used to illustrate the procrastination equation in Steel (2010a).

2 Expectancy corresponds most closely to the commonly measured trait of "self efficacy." The relatively strong correlation between low self-efficacy and procrastination (across 39 studies) is shown table 3 of Steel (2007).

3 In a recent post, Eliezer Yudkowsky claimed that "on a moment-to-moment basis, being in the middle of doing the work is usually less painful than being in the middle of procrastinating." Thus, "when you procrastinate, you're probably not procrastinating because of the pain of working." That might be true for Eliezer in particular, but studies on procrastination suggest it's not true for most people. The pain of doing a task is a major factor contributing to procrastination. This is known as the problem of task aversiveness (Brown 1991; Burka & Yuen 1983; Ellis & Knauss 1977), also known as the problem of task appeal (Harris & Sutton, 1983) or as the dysphoric affect (Milgram, Sroloff, & Rosenbaum, 1988). For an overview of additional literature demonstrating this point, see page 75 of Steel (2007).

4 For an overview of the correlation between impulsiveness and procrastination, see pages 76-79 and 81 of Steel (2007).

5 This is recognized as one of the psychological laws of learning (Schwawrtz, 1989), and plays a role in the dominant economic role of discounted utility (Loewenstein & Elster, 1992). In particular, see the work on temporal construal theory (Trope & Liberman, 2003).

6 The procrastination equation is called temporal motivational theory (TMT). See Steel (2007) on how TMT accounts for every major finding on procrastination. See Steel & Konig (2006) on how TMT draws upon and integrates our best psychological theories of motivation. There are other theories of procrastination - the most popular may be the decisional-avoidant-arousal theory proposed by Ferrari (1992). But a recent meta-analysis shows that TMT is more consistent with the data (Steel, 2010b). An important note is that the full version of TMT places a constant in the denominator to prevent the denominator from skyrocketing into infinity as delay approaches 0. Also, 'impulsiveness' here is a substitute for 'susceptibility to delay,' something which may vary by task, whereas 'impulsiveness' sounds like a stable character trait that might not help to explain having different motivations to perform different tasks.

7 This example taken from Steel (2010a). Academic procrastination is the most-studied kind of procrastination (McCown & Roberts, 1994).

8 Even George Orwell hated writing. He wrote: "Writing a book is a horrible, exhausting struggle, like a long bout of some painful illness."

9 See Cannings et al. (2005) and Newstead (2002).

10 Read chapter 3 of Steel (2010a).

11 In business academia, success spirals are known as "efficacy-performance spirals" or "efficacy-performance deviation amplifying loops". See Lindsley et al. (1995).

12 See Steel (2010a), note 9 in chapter 7.

13 See Hans (2000), Feldman & Matjasko (2005), and World Organization of the Scout Movement (1998).

14 Zimmerman (2002).

15 Aarts et al. (2008), Armitage & Conner (2001), Rivs & Sheeran (2003), van Knippenberg et al. (2004).

16 Levin & Spei (2004), Rhue & Lynn (1987), Schneider (2001), Waldo & Merritt (2000).

17 Achtziger et al. (2008), Oettingen et al. (2005), Oettingen & Thorpe (2006), Kavanagh et al. (2005), Pham & Taylor (1999).

18 Sigall et al. (2000).

19 Aspinwall (2005).

20 A good overview is Weber (2003).

21 Csikszentmihalyi (1990).

22 Miller & Brickman (2004), Schraw & Lehman (2001), Wolters (2003).

23 Steel (2007), Gropel & Steel (2008).

24 Furnham (2002).

25 Klein (2009).

26 Oaten & Cheng (2006).

27 Bandura (1976), Febbraro & Clum (1998), Ferrari & Emmons (1995). This is known as learned industriousness, impulse pairing or impulse fusion. See Eisenberger (1992), Renninger (2000), Stromer et al. (2000).

28 Ainslie (1992).

29 Ariely & Wertenbroch (2002) and Schelling (1992).

30 Locke & Latham (2002).

31 Gropel & Steel (2008), Steel (2010a).

32 Diefendorff et al. (2006), Gollwitzer (1996), Silver (1974).

References

Aarts, Dijksterhuis, & Dik (2008). Goal contagion: Inferring goals from others' actions - and what it leads to. In Shah & Gardner (Eds.), Handbook of motivation (pp. 265-280). New York: Guilford Press.

Achtziger, Fehr, Oettingen, Gollwitzer, & Rockstroh (2008). Strategies of intention formation are reflected in continuous MEG activity. Social Neuroscience, 4(1), 1-17.

Ainslie (1992). Picoeconomics: The strategic interaction of successive motivational states within the person. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Ariely & Wertenbroch (2002). Procrastination, deadlines, and performance: Self-control by precommitment. Psychological Science, 13(3): 219-224.

Armitage & Conner (2001). Efficacy of the theory of planned behavior: A meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40(4): 471-499.

Aspinwall (2005). The psychology of future-oriented thinking: From achievement to proactive coping, adaptation, and aging. Motivation and Emotion, 29(4): 203-235.

Bandura (1976). Self-reinforcement: Theoretical and methodological considerations. Behaviorism, 4(2): 135-155.

Brown (1991). Helping students confront and deal with stress and procrastination. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 6: 87-102.

Burka & Yuen (1983). Procrastination: Why you do it, what to do about it. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Cannings, Hawthorne, Hood, & Houston (2005). Putting double marking to the test: a framework to assess if it is worth the trouble. Medical Education, 39(3): 299-308.

Csikszentmihalyi (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper & Row.

Diefendorff, Richard, & Gosserand (2006). Examination of situational and attitudinal moderators of the hesitation and performance relation. Personnel Psychology, 59: 365-393.

Eisenberger (1992). Learned industriousness. Psychological Review, 99: 248-267.

Ellis & Knauss (1977). Overcoming procrastination. New York: Signet Books.

Febbraro & Clum (1998). Meta-analytic investigation of the effectiveness of self-regulatory components in the treatment of adult problem behaviors. Clinical Psychology Review, 18(2): 143-161.

Feldman & Matjasko (2005). The role of school-based extracurricular activities in adolescent development: A comprehensive review and future directions. Review of Educational Research, 75(2), 159-210.

Ferrari (1992). Psychometric validation of two procrastination inventoriesfor adults: Arousal and avoidance measures. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 14(2): 97–110.

Ferrari & Emmons (1995). Methods of procrastination and their relation to self-control and self-reinforcement: An exploratory study. Journal of Social Behavior & Personality, 10(1): 135-142.

Furnham (2002). Personality at work: The role of individual differences in the workplace. New York: Routledge.

Gollwitzer (1996). The volitional benefits from planning. In Gollwitzer & Bargh (Eds.), The psychology of action: Linking cognition and motivation to behavior (pp. 287-312). New York: Guilford Press.

Gropel & Steel (2008). A mega-trial investigation of goal setting, interest enhancement, and energy on procrastination. Personality and Individual Differences, 45: 406-411.

Hans (2000). A meta-analysis of the effects of adventure programming on locus of control. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 30(1): 33-60.

Harris & Sutton (1983). Task procrastination in organizations: A framework for research. Human Relations, 36: 987-995.

Kavanagh, Andrade, & May (2005). Imaginary relish and exquisite torture: The elaborated intrusion theory of desire. Psychological Review, 112(2), 446-467.

Klein (2009). The secret pulse of time: Making sense of life's scarcest commodity. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Lifelong Books.

Levin & Spei (2004). Relationship of purported measures of pathological and nonpathological dissociation to self-reported psychological distress and fantasy immersion. Assessment, 11(2): 160-168.

Lindsley, Brass, & Thomas (1995). Efficacy-performance spirals: A multilevel perspective. Academy of Management Review, 20(3): 645-678.

Locke & Latham (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. American Psychologist, 57(9): 705-717.

Loewenstein & Elster (1992). The fall and rise of psychological explanations in the economics of intertemporal choice. In Loewenstein & Elster (Eds.), Choice over time (pp. 3-34). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

McCown & Roberts (1994). A study of academic and work-related dysfunctioning relevant to the college version of an indirect measure of impulsive behavior. Integra Technical Paper 94-28, Radnor, PA: Integra, Inc.

Milgram, Sroloff, & Rosenbaum (1988). The procrastination of everyday life. Journal of Research in Personality, 22: 197-212.

Miller & Brickman (2004). A model of future-oriented motivation and self-regulation. Educational Psychology Review, 16(1): 9-33.

Newstead (2002). Examining the examiners: Why are we so bad at assessing students? Psychology Learning and Teaching, 2(2): 70-75.

Oaten & Cheng (2006). Longitudinal gains in self-regulation from regular physical exercise. British Journal of Health Psychology, 11(4): 713-733.

Oettingen, Mayer, Thorpe, Janatzke, & Lorenz (2005). Turning fantasies about positive and negative futures into self-improvement goals. Motivation and Emotion, 29(4): 236-266.

Oettingen & Thorpe (2006). Fantasy realization and the bridging of time. In Sanna & Chang (Eds.), Judgments over time: The interplay of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors (pp. 120-143). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pham & Taylor (1999). From thought to action: Effects of process- versus outcome-based mental simulations on performance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25: 250-260.

Renninger (2000). Individual interest and its implications for understanding intrinsic motivation. In Sansone & Harackiewicz (Eds.), Inntrinsic and extrinsic motivation: The search for optimal motivation and performance (pp. 373-404). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Rhue & Lynn (1987). Fantasy proneness: The ability to hallucinate "as real as real." British Journal of Experimental and Clinical Hypnosis, 4: 173-180.

Rivis & Sheeran (2003). Descriptive norms as an additional predictor in the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analysis. Current Psychology, 22(3), 218-233.

Schelling (1992). Self-command: A new discipline. In Loewenstein & Elster (Eds.), Choice over time (pp. 167-176). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Schneider (2001). In search of realistic optimism: Meaning, knowledge, and warm fuzziness. American Psychologist, 56(3): 250-263.

Schraw & Lehman (2001). Situational interest: A review of the literature and directions for future research. Educational Psychology Review, 13(1): 23-52.

Schwartz (1989). Psychology of learning and behavior (3rd ed.). New York: Norton.

Sigall, Kruglanski, & Fyock (2000). Wishful thinking and procrastination. Journal of Social Behavior & Personality, 15(5): 283-296.

Silver (1974). Procrastination. Centerpoint, 1(1): 49-54.

Steel (2007). The nature of procrastination. Psychological Bulletin, 133(1): 65-94.

Steel (2010a). The Procrastination Equation. New York: Harper.

Steel (2010b). Arousal, avoidant and decisional procrastinators: Do they exist? Personality and Individual Differences, 48: 926-934.

Steel & Konig (2006). Integrating theories of motivation. Academy of Management Review, 31(4): 889-913.

Trope & Liberman (2003). Temporal construal. Psychological Review, 110: 403-421.

van Knippenberg, van Nippenberg, De Cremer, & Hegg (2004). Leadership, self, and identity: A review and research agenda. The Leadership Quarterly, 15(6), 825-856.

Waldo & Merritt (2000). Fantasy proneness, dissociation, and DSM-IV axis II symptomatology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109(3): 555-558.

Weber (2003). Perception matters: Psychophysics for economists. In Brocas & Carrillo (Eds.), The Psychology of Economic Decisions (Vol. II). New York: Oxford University Press.

Wolters (2003). Understanding procrastination from a self-regulated learning perspective. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(1): 179-187.

World Organization of the Scout Movement (1998). Scouting: An educational system. Geneva, Switzerland: World Scout Bureau.

Zimmerman (2002). Becoming a self-regulated learner: An overview. Theory into Practice, 41(2): 64-70.