I asserted that this forum could do with more 101-level and/or mathematical and/or falsifiable posts, and people agreed with me, so here is one. People confident in highschool math mostly won’t get much out of most of this, but students browsing this site between lectures might.

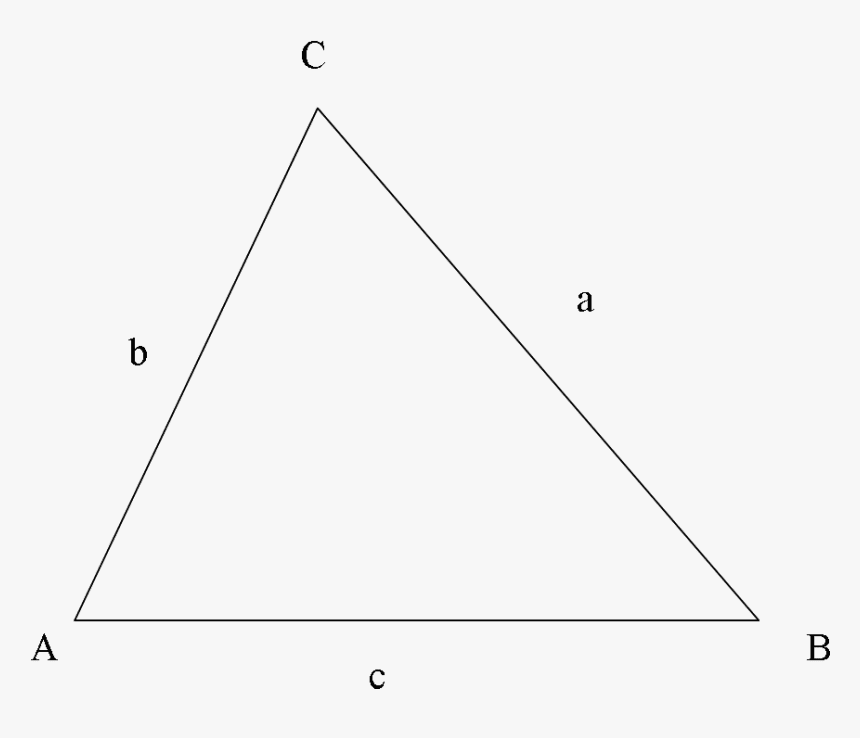

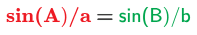

The Sine Rule

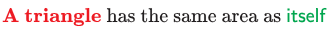

Say you have a triangle with side lengths a, b, c and internal angles A, B, C. You know a, know A, know b, and want to know B. You could apply the Sine Rule. Or you could apply common sense: “A triangle has the same area as itself”. [1]

The area of a triangle is half the base times the height. If you treat a as the base, the height is c*sin(B). So the area is a*c*sin(B)/2. But if you treat b as the base, the height is c*sin(A). So the area is also b*c*sin(A)/2. So a*c*sin(B)/2 = b*c*sin(A)/2. And if you divide through by abc/2, you get sin(B)/b=sin(A)/a.

In practice, you might be well-advised to just recall and regurgitate the relevant equation. But notice that this is literally equivalent to the informal version.

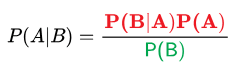

Bayes’ Theorem

A demon-hunter has a 10% chance of encountering an archdevil on a given mission. A demon-hunter who doesn’t encounter an archdevil has a 80% per-mission survival rate; for a demon-hunter who does, that number is 30%.

Say you know a demon-hunter survived their latest excursion, but don’t know anything else, and want to calculate the probability they encountered an archdevil. You could apply Bayes’ Theorem. Or you could apply common sense: “Things that couldn’t have happened didn’t” and “Probabilities add to 1” (arguably with a little assistance from "Odds ratios aren't affected by tests that don’t distinguish between them”).

Before you get the good news, the four possible outcomes are:

- met archdevil & survived (3%),

- met archdevil & died (7%),

- avoided archdevil & survived (72%), and

- avoided archdevil & died (18%).

After you get the good news, the only paths which could have been taken are met&survived and avoided&survived. But those two only have 75% probability between them, and probabilities add to 1, so they get scaled up appropriately, by multiplying through by 1/0.75. This gives you a 4% chance that they met an archdevil, and a 96% chance they didn’t.

(The part I gloss over is probabilities preserving their proportions.[2] But, like, of course they do! If you bet that a fair die will roll above three, and later find out you won – eliminating 1, 2 and 3 as hypotheses – do you think something like “all the probability from the eliminated hypotheses must have gone into 4”? No, you think “4, 5, and 6 are equally likely rolls based on what I know, so there’s a 1/3 chance it was 4”.)

In practice, you might be well-advised to just recall and regurgitate the relevant equation. But notice that this is literally equivalent to the informal version.

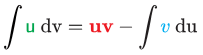

Integration By Parts

Say you want to integrate (x^2)(e^x). You could repeatedly apply integration by parts. Or you could repeatedly apply common sense: “If you differentiate something which produces your target, you’ll get your target, but you might also get some other stuff, which you’ll have to deal with”.

If you differentiate (x^2)(e^x), one of the outputs you’ll get is (x^2)(e^x). You’ll also get some other stuff, in this case (2x)(e^x). So you also need to figure out what to differentiate to take care of that. If you differentiate -(2x)(e^x), one of the outputs you’ll get is -(2x)(e^x), which cancels the (2x)(e^x). You’ll also get some other stuff, in this case -2(e^x). So you also need to figure out what to differentiate to take care of that. If you differentiate 2(e^x), one of the outputs you’ll get is 2(e^x), which cancels the -2(e^x). But you’ll also get some other stuff, in this case 0.[3] So you also need to figure out what the differentiate to take care of that.[4] If you differentiate any number that doesn’t have a variable next to it you get 0; this can be represented by a “c”. So the total answer is (x^2)(e^x) – (2x)(e^x) + 2(e^x) + c (by convention we say +c even when -c would make more sense; it doesn’t matter, since “any number” can be negative just as easily as positive).

In practice, you might be well-advised to just recall and regurgitate the relevant equation. But notice that this is literally equivalent to the informal version.

Conclusion

You didn’t need to know any of this. You can just apply the equations and get the right answers. And of course you already assumed they were all proven somehow, even if you didn’t know the details; I won’t insult you by claiming you needed to be taught that. The dumb, subtle thing I’m trying to gently bludgeon into you – which I worry your teachers didn’t – is the closeness with which the math can match the meaning, if you take the time to make sense of it.

- ^

It’s possible to solve this even more simply with “a triangle has the same height as itself”, but that doesn’t map as cleanly to the standard expression.

- ^

“When you eliminate the impossible, whatever remains has probability proportional to the probability it had before you eliminated the impossible.” - Sherlock Holmes, probably, before Watson butchered the quote.

- ^

Technically you were getting this at every step, but it’s easier to treat all the 0s as one big 0.

- ^

Wait, are you saying you can conceptualize the “+c” thing as a consequence of integration by parts? I never thought of it that way! Buddy, you can conceptualize most things as most other things, ask any poet. But to answer your question . . . yes, you can.

I think you could've done better with integration by parts.

In physics, integration by parts is usually applied for a definite integral in which you can neglect the uv term. Thus, integration by parts reads: "The integral of udv = integral of -vdu, that is, you can trade what you differentiate in a product, as long as the functions in question have a small integral over the boundary".

Common examples are when you integrate over some big volume, as most physical quantities are very small far away from the stuff.

I also think the intuition behind Bayes rule as usually interpreted here on LW, that is, it provides the updating rule posterior odds = prior odds*likelihood ratio and thereby also provides a formalization of how good evidence is. As for the derivation from P(A|B) defined as equal to P(A and B)/P(B), I think this is best described by saying that P(A|B) is the probability of A once you know B, so you take the mass associated to the worlds where A is true once B is true and compare to your total mass, which is the mass associated to the worlds where B is true. The former is really just "mass of A and B", so you are done.

Now, P(A and B) = P(B)P(A|B), which I think of as "First, take probability B is true, then given that we are in this set of worlds, take the probability that A is true". Essentially translating from locating sets to probabilities.

From here, Bayes theorem is the simple fact that A and B = B and A. So P(B)P(A|B) = P(A and B) = P(A)P(B|A). If you draw a square with 4 rectangles where the first row is P(A), where the second row is P(-A), where the first column is P(B), and where the second is P(-B), and each rectangle represents a possibility like P(A and -B), then this equation just splits the rectangle P(A and B) into (rectangle compared to row) * row = (rectangle compared to column) * column. Divide by P(B) (that is, the row) to get Bayes law.

For the sine rule, I think it also helps to show that the fraction a/sin(a) is the diameter of the circumcircle. Wikipedia has good pictures.

For an extra math fact that totally doesn't need to be in the post, it is interesting that for spherical triangles, the law of sines just needs to be modified so that you take the sine of the lengths as well. In fact you can do similar in hyperbolic space (by using sinh), and there's a taylor series form involving the curvature for a version of sine that makes the law of sines still true in any constant curvature space. (you can find this on the same wiki page).