I have started using a visual metaphor to diagram biases in my attempts to remove and mitigate them in myself. I have found this to be incredibly useful, particularly when dealing with multiple compounding biases.

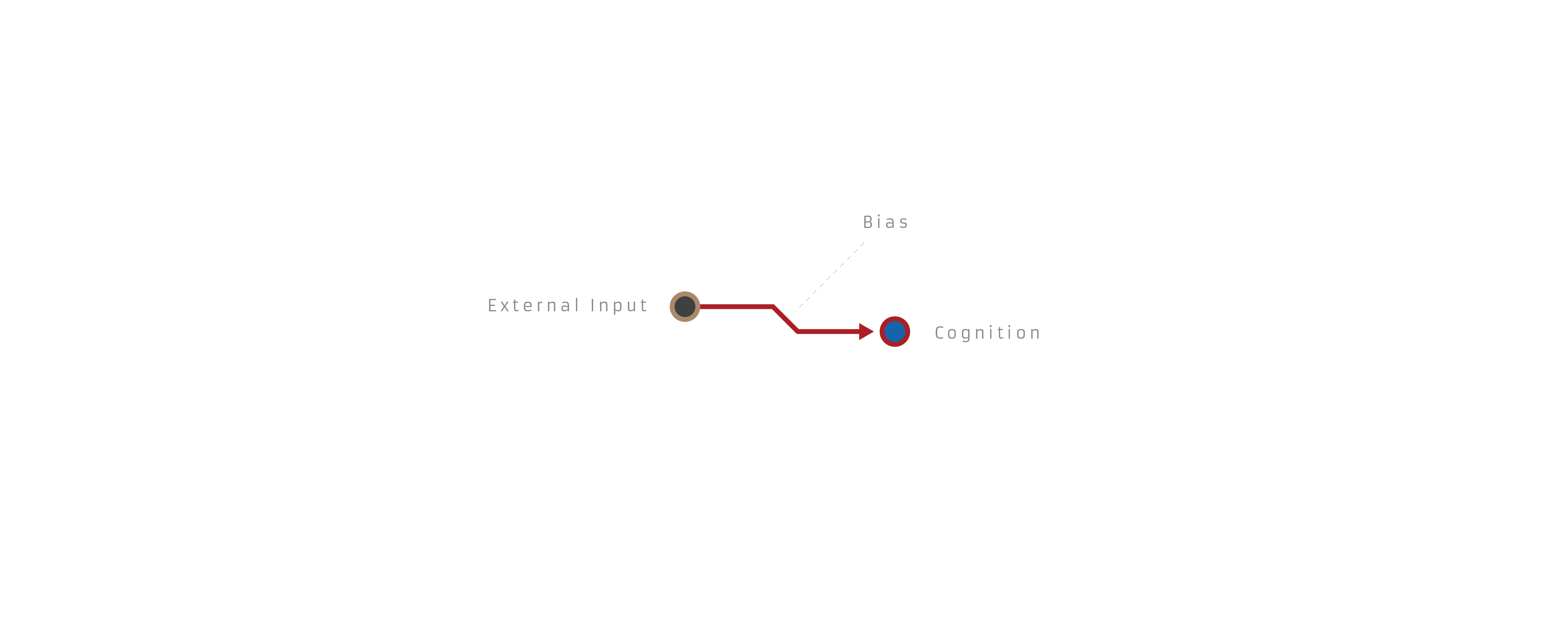

I view an inference as an interaction between external inputs/premises and the resulting cognitions/conclusions. It can be read either as "if x then y," or "x therefore y." A basic inference looks like this:

A biased inference looks like this:

This is obviously a simplification of complex cognitive shit, but it's meant to be more of a functional interface than any kind of theory.

So to run through a few example biases, the fallacy of the undistributed middle:

The planning fallacy:

Planning fallacy corrected:

A little awkward, but it can capture basic failures in Bayesian reasoning as well:

Bayesian reasoning corrected:

And an example of compounding biases resulting in a distorted worldview:

I'm curious if anyone sees downsides to this framework, has other ideas to improve it, or thinks I'm hopelessly naive for even trying to capture human reasoning in a tidy diagram.

You are a step ahead of my latest post with the CBT comment. Good points on being able to write out thought chains and add distortion notation later and symbols for common biases. Have you seen examples of belief network diagrams used in this way?