(This post contains some thought about gACI)

What does it mean that I have free will? If we can define free will like this:

If in a deterministic universe, no observer B can 100% correctly predict the behavior of subject A, except when B is in the future of A, we can say that subject A has free will.

We can prove that free will does exist in a universe where light speed is not infinite, even when we don’t consider quantum randomness. Here is the proof:

In a deterministic universe, the information of an event A (or in other words the behavior of a subject A) can be completely known, only if its prior states (or its causes) are completely known.

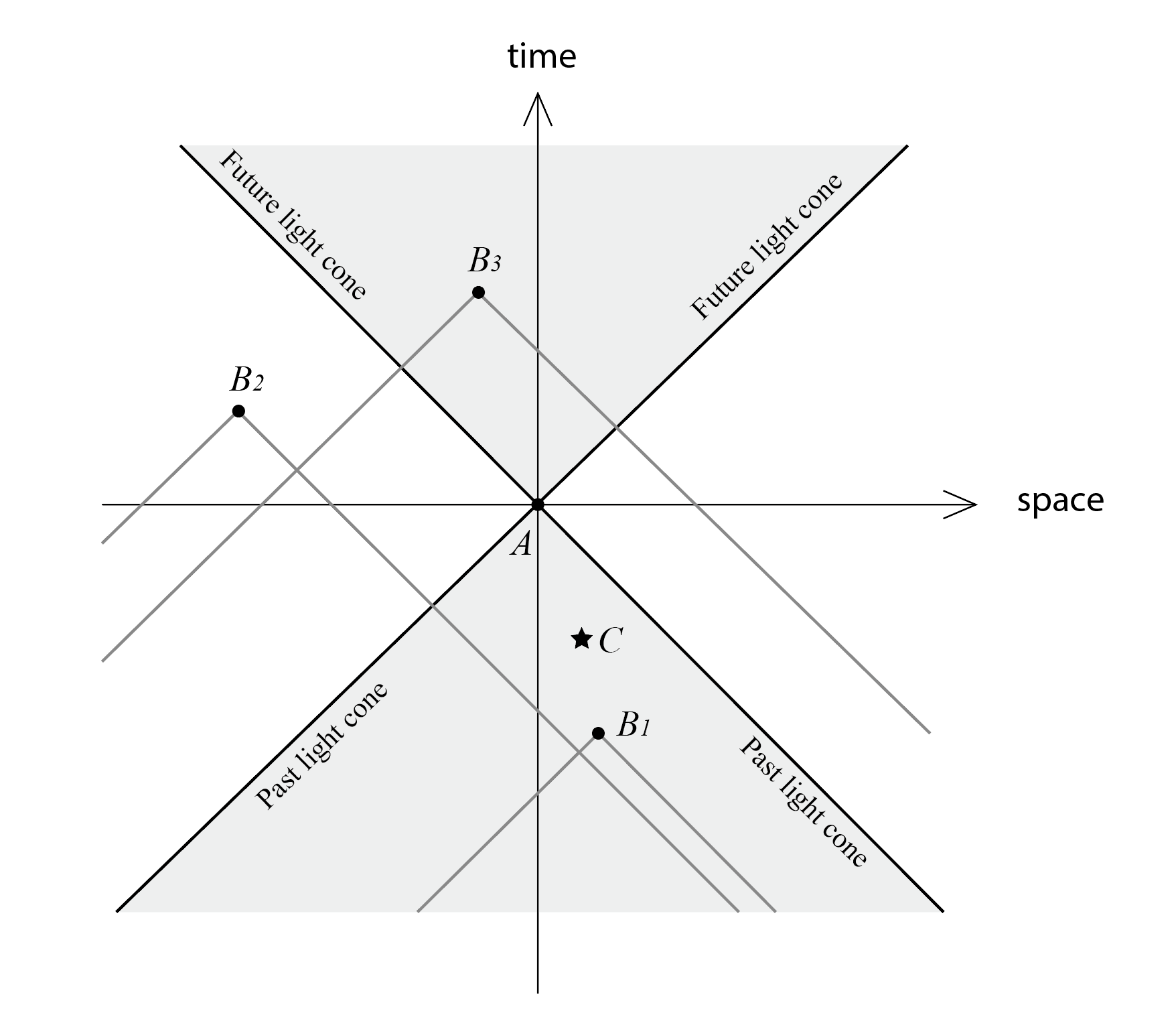

In a universe where light speed is not infinite, all the causes of an event A, lies on or inside its past light cone. If you don’t know all the causes of the event A, there will always be some uncertainty about A.

According to this picture, we can see that only observer B3 is able to know all the prior states of event A, because B3 is in the future of A. It’s impossible for B1 and B2 to know, for example, event C which may affect event A. Because C is not inside or on their past light cone.

For example, when you are chatting with your friend, you will never be able to anticipate that there might be a gamma ray photon hit their brain neurons from the far side of you and unpredictably change their mind.

(Some people may argue that there’s no free will in the presence of an all-knowing God. But that’s another story.)

This strikes me as a very unintuitive definition of free will.

We often talk about free will experientially; defining it based on a specific external observer strikes me as odd. But before I critique that in any way, I'd love more clarification on what you mean by "observer." Is this anything capable of prediction (e.g. a faithful simulation of the universe)?

But more importantly, I think "100% correctly" is doing the bulk of the work here. I fully agree with your claim that if we define free will in a manner similar to this, we will never reach it. But really, very little outside of statements within self-contained axiomatic systems can ever be held to the standard of 100% certainty. If your concept of free will hinges on the realistically minuscule chance that a random event will alter your decisions substantively, then I ask if this conception still resembles anything like the idea of "free will" as we tend to think of it.

Overall, I concede your claim follows from your definition. But I question the usefulness of such a definition in the first place. I think we can all agree that we cannot have 100% predictive certainty. The question is more whether or not we want to call that shred of uncertainty "free will." Semantically, I think it's confusing to call this "free will" when that is not usually the intended meaning of the phrase, but ultimately the decision is somewhat arbitrary as our experience remains the same regardless.

I want to define "degree of free will" like: for a given observer B, what is the lower limit of event A's unpredictability. This observer does not have to be human, it can be an intelligence agent with infinite computing ability. It just does not have enough information to make prediction. The degree of free will could be very low for an event very close to the observer, but unable to ignore when controlling a mars rover. I don't know if anybody has ever described this quantity (like the opposite of Markov Blanket?), if you know please tell me.

I like... (read more)