Here we go.

To recap:

Last week I wrote about what happened when I applied metrics to my piano practice, in which I outlined the “secret to learning” in eight steps:

- Define win condition.

- Define action you are going to take to achieve win condition.

- Take defined action.

- Evaluate action both against its original definition (that is, did you do what you said you were going to do or did you do something else) and against the win condition.

- Ask yourself what is keeping you from achieving your win condition. Describe it as specifically as possible.

- Define action you are going to take to solve/address/eliminate obstacle preventing win condition.

- Repeat 2-7 until win condition is achieved.

- STOP.

Step #8, “Stop after win,” has prompted significant discussion both in various subsets of the internet and in various rooms of our home. It goes against the standard practice (pun intended) of repeating a learned skill multiple times after the first accurate recall, otherwise known as “playing it five times correctly.”

Is it better to stop after an accurate recall, or to immediately repeat?

If I’ve got it wrong, that’s good news. I’ll say “WOO-HOO-HOO, I LEARNED SOMETHING NEW” and update my practice strategy accordingly.

But let’s do some more investigating — and share the initial results of a randomized experiment.

There are two arguments in favor of immediate repetition:

- Immediate repetition allows you to confirm that you know something.

- I have no counter-argument for this. I agree.

- Immediate repetition increases the win/fail ratio. If you fail at a passage four times and win once, what is your brain likely to remember the next day — the four fails or the one win? If you can generate four fails followed by five wins, your brain should be more likely to remember the win condition.

- My first counter-argument is that this only works if you can actually generate five consecutive wins in a row. What happens if it looks more like FFFFWFWWFW? What’s your brain going to remember then?

- I’m also going to counter-argue — and my entire post was going to be on this particular topic, when I originally set out to write it — that accurately describing why you failed and what you need to do differently next time does as much to strengthen your neural network as an accurate pass. Conversely, you can weaken your neural network by playing the passage over and over without stopping after each pass to evaluate what happened.

There are also a few arguments in favor of stopping after an accurate recall:

- As I mentioned in my last post, STOP AFTER WIN means that you are always returning to a passage from a WIN CONDITION. You got this last time, which means you can get it this time.

- The counter-argument is, obviously, but what if you don’t get it right the first time you play it during the next practice session? This appears to be the most relevant counter-argument and the biggest potential issue with the practice.

- Double-checking leads to fail loops. You either look at the stove once, observe that it is off, and go about your day — or you look at the stove, observe that it is off, take a few steps away, ask yourself if you really paid attention, turn around, look at the stove again, observe that it is off, walk out of the kitchen, ask yourself how you can trust your observation this time if you didn’t trust it the last time, turn around, stare at the stove for a while, point at every burner and say “off,” leave the kitchen, get halfway up the stairs, and turn around again.

- The counter-argument could be “but if you do this for piano then you will be really really certain that you know something,” to which my counter-counter-argument is “no no no you don’t understand, every time you double-check you are reconfirming a mental state in which you are not sure whether you know something.”

- Then you’ll say “what about checking your work in school, your math worksheet and your spelling test and so on” and I’ll say “yes yes yes checking once is good, very good, find your errors and fix them, but repeatedly checking over and over leads to mental discreditation.”

One commenter suggested that I run an experiment in which I flip a coin to determine which path to take — STOP AFTER WIN or REPEAT AFTER WIN.

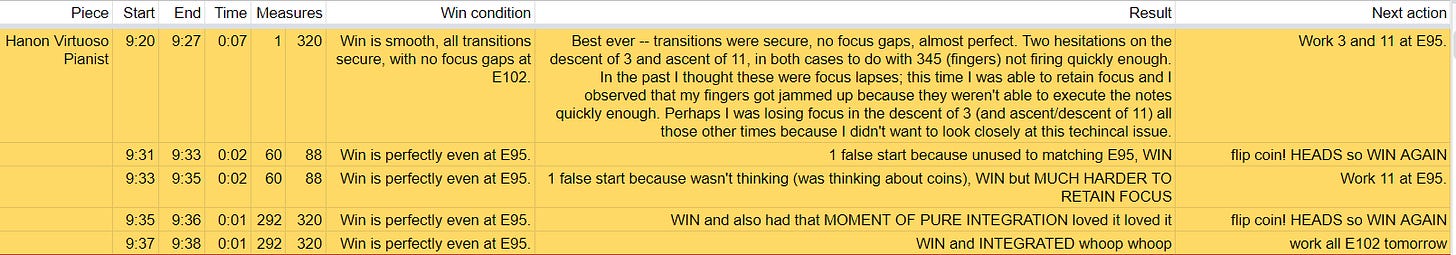

Here are the results from this morning’s practice session:

I know that is probably hard to read, but in this case I played Hanon exercises 1-11 in full, identified two technical errors I wanted to correct (please note that these were not missed notes, these were fourth-finger-being-slower-than-other-fingers errors), isolated the measures in which the errors were present, played the first isolated section, WON, flipped the coin, got heads, WON again (but noted that it was “much harder to retain focus”), played the second isolated section, WON, flipped the coin, got heads, WON again.

All very good, right?

Sure — for a warmup.

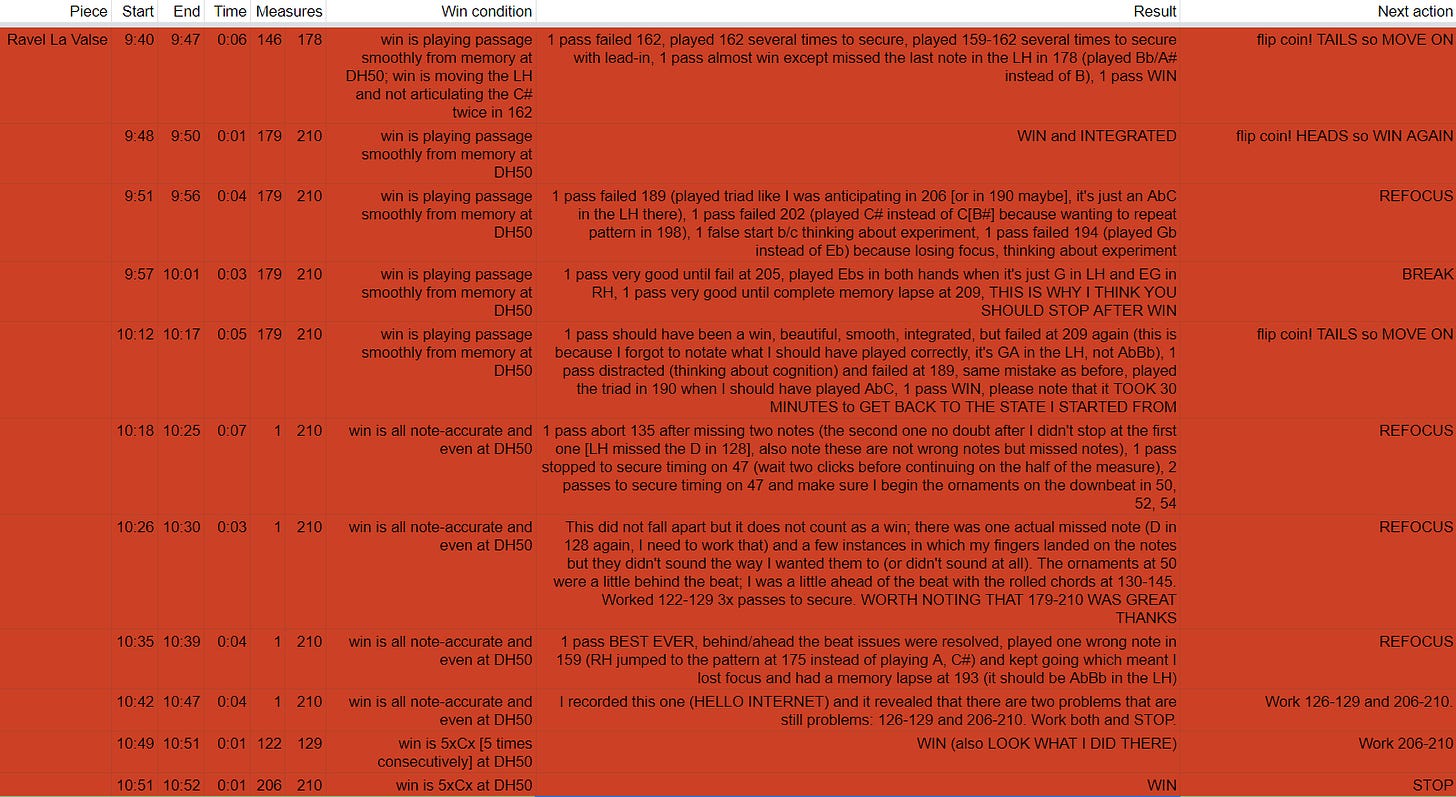

Here’s what happened when I ran the same experiment on Ravel’s La Valse (four-hand duet, prima part):

At the end of my last independent practice session, measures 1 through 210 were all at WIN CONDITION (defined in this case as memorized, note-accurate, and even). When I worked on the piece as a duet with L last night, we identified a more efficient fingering that could be used in measure 162 — so I began today’s practice session by solidifying that change and winning measures 146-178.

Flip coin, tails, STOP AFTER WIN.

Then I played measures 179-210. I won these during my last session, and I won them this time around. This is how the system is intended to work.

I flipped the coin.

Heads.

I spent the next thirty minutes trying to pull off another win. Practice notes include “losing focus” and “thinking about experiment” and “complete memory lapse.”

This could be my fault — I mean, it is obviously my fault — in the sense that someone else might be able to pull off repeated wins in a similar experiment.

But my data is so far indicating that second-guessing something you just won only leads to confusion.

You’ll notice, if you pay close attention to the spreadsheet, that I found a potential loophole in all of this.

For short sections of music, the kind of passages that may only take a minute or two to play, you can define WIN as “achieve win condition five times consecutively,” or “WIN 5xCx.” This could potentially give us the best of both worlds (and/or I could have just reinvented the wheel).

That won’t work for larger sections of music, because five consecutive wins could take you a full hour to play even if you get five winning passes the first time you try.

And I’m still uncertain about whether that’s a good idea — as I was telling L the other night, playing a 5-minute section of a difficult piece (or a 15-minute piece in full) might be the kind of thing you can only do once a day.

“If you do it right,” I argued, “you have to give it everything you have, which doesn’t leave anything left over for a repeat performance.”

“Why would that be the case?” he argued right back. “If you really know something, you should be able to repeat it accurately as often as you want to.”

I’ll end by sharing the video I took of my last pass through measures 1-210 of Ravel’s La Valse (before identifying and working two errors):

If you were me, how would you manage your next practice session? Stop after win? Update all win conditions (that take fewer than two minutes to execute) to 5xCx? Keep flipping that coin? ❤️

Fatigue is real. Even machines can't repeat actions indefinitely without needing a rest or maintenance. A more relaxed version of L's statement is true, in that the ability to repeat something accurately more than once is one way to measure how well you know something. I'd expect this measure to correlate with, say, the ability to reproduce the piece in performance - but imperfectly. At a certain point, other constraints become binding. Have you practiced in front of an audience? On a piano other than your own, in a room other than where you're used to practicing, in a different emotional and physical state than you're used to?

I'd also caution that defining your "win" condition as "played the passage X times perfectly" has an Achilles' heel, which is that it incorporates a lot of randomness. If you think of each play-through as having a P% probability of success, then you can achieve the win condition at an arbitrarily low value of P by playing a sufficient number of times. This can lead to frustration (if it goes on too long without success) or to illusory success (if you get lucky).

The way I've always suggested my students cope with this is by selecting the dimensions of their passage intelligently. They should pick a passage length that they feel confident they can play correctly on their first or second try. if that fails, they should shorten the passage significantly and try again, until they've found a portion of the passage - even a single note or chord - that they can play on their first or second try. Then they can start trying to combine these fragments into a longer whole.

This tends to be uncomfortable at first, because a good composer writes their music in such a way that you always want to hear one more note - kind of like how a good video game makes you want to play just one more turn. It also forces students to break out of their ruts. But, especially with adult students, they've tended to like it once they get used to it and find that it's helpful to them.

I like the idea of a piano performance ladder! Gives some built-in social validation to the work of learning piano music.