[Confidence 50%, this is speculative and good counterarguments will improve my view of these matters.]

I.

When I do moral philosophy, I am looking for a usable repeatable framework for analyzing moral decision-making in a very broad range of cases. I accept that moral philosophy is an inexact science and cannot be made into a machine that mechanically outputs the right answer. There are simply too many parameters that go into real decision-making to make a moral philosophy complete in the way that an account of electro-magnetism is.

But I would like for something that doesn’t fall flat on its face at the first objection. The standard Thomistic framework is a great starting point but is locked in intractable controversies. Perhaps chief among them is how to identify what an act is.

You see, ‘action’ is one of the three key metaphysical categories by which we judge praiseworthiness or acceptability of an action in the Thomistic system.

You know the rhyme:

With Intentions Good, the mind is right.

An act acceptable gives hand its might.

And should an evil too befall

Let pain be healing, evil forestall.

Or if lists are your preference:

- Your intention must be toward the good ends, not the bad ones which may result from the action. Cause a stinging pain in your child’s knee to clean the wound, not see him bleed.

- The act must be acceptable in itself. That is, it cannot be one of things that “we just don’t do” no matter what.

- There must be proportionally good outcome that is not caused by the bad outcomes. You can kill to protect your home, but you cannot kill to collect better data on death rattles. Generally, we group all the considerations that include causal chains, uncertainty, consequences, and proportionality into one bucket called “Circumstances.”

I have always been troubled by step 2. For many years, I denied the existence of the “act itself” for moral analysis. What is the act, I thought, but the marriage of intentions with the mechanical actions to make them happen. The twitching of fingers, the vibrating of vocal cords, the speaking of vows, the motions of homework these are not meaningful at all in themselves. The circumstances and intentions give them meaning. A philosopher might say abortion is unacceptable in itself, because “the whole life is sacred from conception to natural death” belief commitment.

I would respond in two ways: One abortion is a noun not a verb. The acts that make it up vary a lot and so there is not one act called “an abortion.” And then, since this is a bit obtuse to most, I would point out that there are actions that have the same effect which are acceptable in some circumstances, i.e. removing an ectopic pregnancy. What matters in the moral analysis are not the actions but the intentions and circumstances, even for the person categorically against abortion.

Another thing that I have trouble with is how to identify an act. We might say that playing baseball is an act. But is it? Isn’t playing baseball made of swinging, catching, throwing, running, shouting. Those are the acts, no? Or maybe swinging isn’t an action. Swinging is composed all sorts of subparts that make up the reified action of swinging?

Is vowing an act distinct from speaking? Isn’t it the circumstances of the words that make a speech act a vow as opposed to the words themselves? Aren’t words themselves social conventions anyway? And thus, identifying an act is just abiding by a specific social convention. A vow is an act. Marriage is an act. Life itself is one great deed.

I am revising this view. My motivation is that I think we should have a category of actions that we do categorically rule out. Yes, the category will be fuzzy, but a good life requires being the type of person who can draw a hardline at times to say, “This I simply will not do, and no argument or circumstance will make me do it.” I am talking about exceptionless moral norms. We should live by rules which over many iterations will lead to a better society and protect us from our worst habits of casuistry to justify viciousness. Exceptionless moral norms do this by saying that there are some powers of judgment we cannot trust ourselves to exercise. None of us can wield unfiltered moral reasoning, and if we coordinate around some universalized principles, we will save ourselves from self-destruction.

Are there circumstances where torture may be justified? Perhaps there are. But whom do we trust to correctly identify those circumstances when they have power? No, we want the dark powers chained, buried in the sea, or set beyond our grasp.

I don’t know what the exceptionless moral norms are. But I do want a way to preserve them. They are important Schelling points for behavior, guide action, and decrease the frequency of the worst offenses.

II.

Before continuing, I would like to revisit our terms.

- Intention: A person’s intention is to complete all the acts and cause all the effects which lead to their desired end. Some of the effects might be necessary (or probabilistic) consequences of their actions but are not necessary to the end. These effects are foreseen, but not intended.

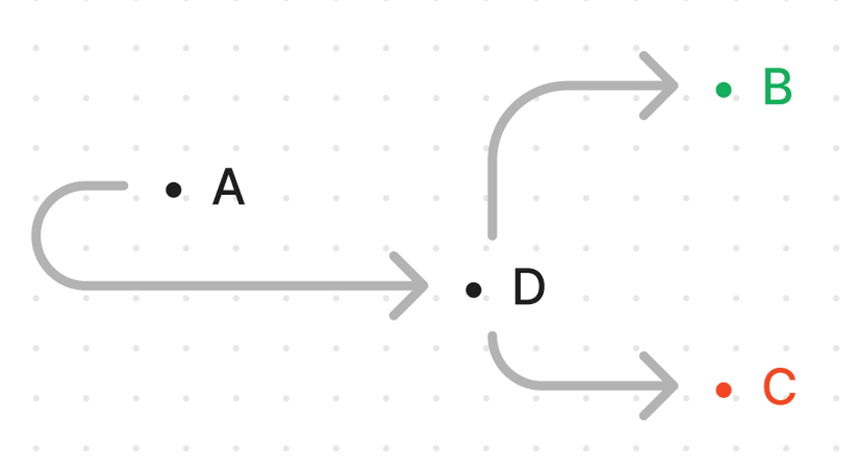

For example, hitting a home intruder with my home defense flashlight causes his unconsciousness and my safe home, but his unconscious state, while foreseen, is not strictly speaking intended. The intended state is the safety of my home. You should think of this as a standard Pearlian causal inference diagram. One action leads to two states. Those states are causally conjoined by the action, and the logic of language says the unconscious person causes the safety of the home. But ignore the logic of language: states do not cause states. Actions cause states. The action causes both consequences.

An intention is known by external actions chosen. If a person claims that they intend to learn, but instead cheats on their assignments, then they haven’t learned, nor was the cheating part of that intention. How we judge a person’s intention is by what acts they chose to do. This is both how legal system works and how common sense operates. If you plan to assassinate someone, but do so in a way that causes a lot of unnecessary collateral damage as well, then your intention should rightly be inferred from the specific actions you took. This is essential for understanding the act itself discussion. - An act is acceptable in itself, if it upholds exceptionless moral norms. That is, it preserves the essential character of the good intention.

My go to example is taken from Steve Coll’s Ghost Wars. In 1998, Osama bin-Laden was being tracked. The US was 50% sure he was in a compound in Kandahar and special ballistics and mapping experts were busy calculating how the compound could be bombed in such a way as to collapse as few as possible of the surrounding domiciles. In the end the president, decided against bombing on such a probability of success, given the number of civilian casualties that would likely result, some around 60. What catches my eye about this story is that the ballistics experts are not only supposed to measure how to destroy the target, but also how to minimize collateral damage and unnecessary loss of life. If you want to act morally your actions need to show that you don’t intend the evil effects of a bombing.

Everything that occurs between two end states in a causal diagram is the act. - Circumstances. These are the relative weights of the good and bad effects of the action, the uncertainty around these, relationships between people and institutions, the norms and obligations that are affected by the action. These all have some bearing that allow for judgements of proportionality, acceptability, and blameworthiness/ praiseworthiness of an action.

III.

With these redefinitions, we have a reason to think about exceptionless moral norms for actions, but then we suddenly have an issue about how to identify whether an action is within the bounds or not? A standard retort is to make the indirect/direct distinction and either argue, prohibition breaking must be either indirectly voluntary or indirectly caused by the agent.

What does it mean to indirectly vs directly to cause a harm? It is this distinction that I primarily object to and think needs reframing.

Is it how many mechanistic events intervene between your action and the effect? If I cut someone’s hand with an axe, that is more direct than if I cut their hand with a Rube Goldberg machine.

But would you call killing with gun which has a series of intervening events(trigger, hammer, gunpowder, combustion, propulsion) less direct than killing with a sword? All else held equal we wouldn’t consider these different moral acts at all. In a causal diagram necessary/inexorable effects do not need to be modelled.

Maybe the difference between indirect and direct is probabilistic?

If your action contributed to an effect, but was not sufficient to cause it then it is indirect.

But would all doctor’s prescriptions and most medical interventions then be considered indirect? That’s crazy talk, I think, for we would hold doctors responsible for unnecessary risk-taking and foreseeable harms even if they are only probabilistically going to occur. The probabilities matter for the intended effect, but the direct vs indirect distinction does not add anything.

Possible scenarios in this causal diagram.

| A | Home intruder | Sick patient | Not feeding prisoner -omission |

| D | Attack intruder with heavy flashlight | Medical prescription | Torturing prisoner- commission |

| B | Safe home | Healing | Important information |

| C | Unconscious intruder | Side effects | Harmed prisoner |

The claim of the indirect/direct distinction is that if Action D leads to both a good effect and the bad effect. Action A leads to the good effect and bad effect just as well, but makes our voluntary actions more distant the bad effect it is, all else being equal, it is the more praiseworthy action. I am not exactly sure how this could be.

In the final column, I posited an commission-omission distinction. I have a problem with that distinction, but perhaps in light of the above argument...

Maybe it works like this? Action D is an exceptionless moral norm, but Action A, which causes state D is not. So we should prefer A, even if it seems like a fiction since D is caused anyway? Maybe avoiding dirtying our hands is an aspect of morality worth upholding.

This is all a response to SEP 4.4. The whole article is very good! https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/double-effect/

I look forward to your thoughts on how you would think through the idea of direct/indirect distinction mattering.

Perhaps your flashlight-clobbering story is permissible according to Aquinas (though I find his account of things insufficiently precise to tell), but it is definitely not permissible according to the accounts described in the SEP entry you linked to. You are protecting your house by means of injuring the intruder, and those accounts say explicitly that the DDE says that if you're forbidden to make bad thing X happen then you are likewise forbidden to make bad thing X happen in order to achieve good consequence Y of X. What you're allowed to do is to do something that produces both Y and X for the sake of Y, but Y has to happen in a way that isn't a consequence of X.

Perhaps you can claim that actually the protection of your house isn't happening by means of injuring the intruder. (You're just trying to scare him off and cause him some pain, and it's just too bad that in the process you fractured his skull[1].) And maybe in that case your action is in fact permissible according to the DDE. But, once again, I say: if so, so much the worse for the DDE. The permissibility of clobbering an intruder with a flashlight and predictably injuring him should not depend on whether there's some other mechanism by which your action might have protected your house, when you know that in fact that's not how it's going to play out.

[1] I'm tweaking the scenario a little in order to make the harm done something that's more plausibly Something Not Allowed.

If your intention was just to scare him off and cause him some pain, and you weren't at all expecting to end up fracturing his skull, then I don't think you need the fancy double-effect stuff: you can just say that you're not morally liable for unexpected, unpredicted consequences of your actions, provided your expectations and predictions were arrived at in good faith.

It is very possible that I'm missing something here. I have the impression that you have studied this stuff quite a lot more than I have, so if I think you're completely wrong about something fairly basic then I should take very seriously the possibility that the error is actually mine. But I don't see what my error might be here. Do you disagree that in your scenario you're getting the good effect (safe home) by means of the bad one (injured intruder)? Or do you disagree that the analyses of the DDE in the SEP say you're not allowed to do that? Or what?

I think it's worth distinguishing "has an explicit discussion of double-effect" from "has a special way of handling double-effect cases". As you say, standard-issue Benthamite utilitarianism has a way of dealing with such cases (i.e., just put them through the same machinery as all other cases and turn the handle) even though it doesn't do anything special about them. Isn't that likewise true for Aristotle, Kant, et al?

I am not an expert on either Aristotelian or Kantian ethics. But my crude model of Aristotle says: ethics is about being a person of good character, and what you should do about this sort of puzzle is to become a person of good character and then act in whatever way that leads you to act. And my crude model of Kant says: ethics is about obeying moral laws whose universal application you endorse, and what you should do about this sort of puzzle is to find moral laws whose universal application you endorse and then do what they say. Neither of these in itself resolves the puzzle, but then the same is true for Bentham's principle of utility (you should take whichever action leads to the greatest net excess of pleasure over pain). All of them provide tools you can use to pick an answer. None of them says that you need some sort of special-case rule just for these situations. Benthamite utilitarianism arguably has the merit of giving (in principle) a more specific and well-defined answer.

As for what exactly should be considered part of a person's "intent", I think I prefer not to think of things in those terms; I am not convinced that the difference between "I intended to knock the intruder out and thereby protect my home" and, say, "I intended to hit the intruder in a way that would stop him further invading my home, and correctly anticipated that the way this would happen is that I would knock him out, but I didn't intend that specific consequence" is very clear-cut, nor that it should be morally significant. I would prefer a different analysis: as you contemplate what you might do about the intruder, you anticipate various consequences and have whatever attitudes toward them you have, and I think those attitudes can be morally significant. Did you know you were going to knock him out or not? Were you hoping to hurt him, or hoping to cause him as little pain as possible? How did these predictions and attitudes influence your choice? Etc. If, say, you predicted that your action would knock him out and possibly cause lasting brain damage, and you tried to strike him in a way that would maximize the chance of unconsciousness and subject to that minimize the chance of permanent damage, then all of that is relevant, but whether we classify your action as "intended to knock him out" or "intended to protect your home" is not.