Yes I’m talking about grammar. The present perfect tense describes actions that happened in the past but are relevant in the present. You say, “I have seen that movie,” meaning you saw it in the past, but what’s important is that presently you are a person who saw it.

How is a verb tense ruining my life?

There’s a world of difference between wanting to do something and wanting to have done something.

I’m not the first to find this distinction interesting:

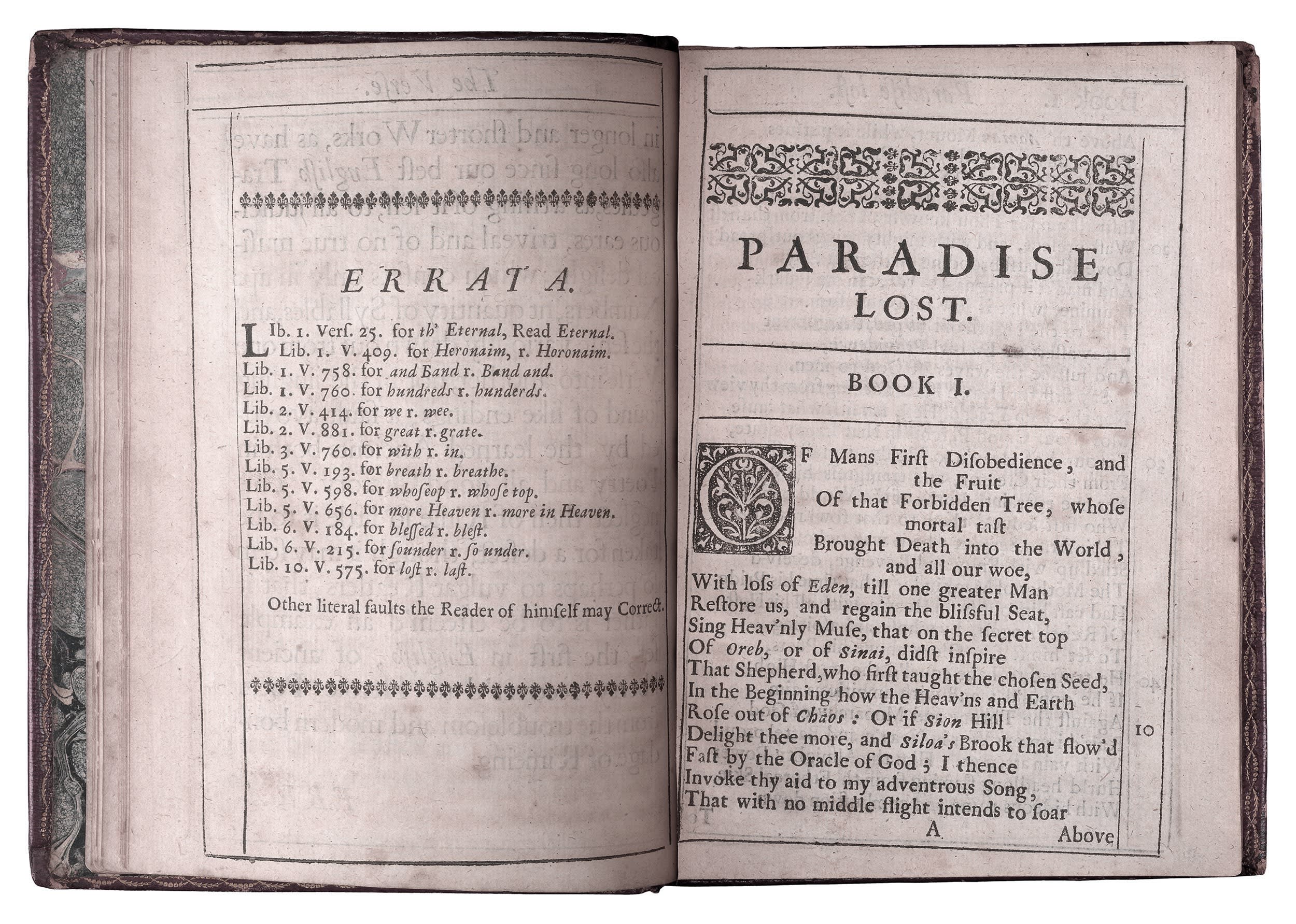

I don’t believe any of you have ever read PARADISE LOST, and you don’t want to. That’s something that you just want to take on trust. It’s a classic, just as Professor Winchester says, and it meets his definition of a classic — something that everybody wants to have read and nobody wants to read.

Mark Twain, “The Disappearance of Literature”

What’s dangerous is when we conflate the two tenses. We say, “I want to do X,” when really we want to have done X. I’ve often caught myself doing this, and I see others doing it too. It’s a form of deception (usually self-deception), and it sets us up for failure and frustration in our efforts.

Let’s talk about the nature of this mistake, why we make it, and how it comes back to bite us.

so fun

What does it mean to want in the present perfect tense?

Let’s look closely at the difference between wanting to read Paradise Lost and wanting to have read Paradise Lost.

Wanting in the present tense is simple: when you want to do something, your desire is for the act itself.

Wanting in the present perfect tense is tricky: when you want to have done something, your desire is for a future state where you already did the thing and acquired the memories/experience of it.

Notice the language there—you acquired something, like you’re doing work and getting a paycheck at the end. In fact even the original wording implies this: in English, we use the word “have” both to mean possession and to construct the present perfect tense (“I have a car” / “I have been to Florida”). That’s not a coincidence! You can see how statements in the present perfect tense could also be interpreted as statements about possession: saying I have been to Florida is basically the same as saying I have (i.e. possess) the experience/memory of being in Florida. This double usage of the verb “to have” goes all the way back to Latin.

So the present perfect tense is fundamentally about owning/possessing something. It’s not about doing.

Sometimes people really just want to have read Paradise Lost, and they definitely don’t want to read it. They find it dry and dense and long from beginning to end, but they would enjoy having it “under their belt” at the end.

The lie

But you’ll notice nobody says “I want to have read Paradise Lost” or “I want to have done X.” It’s so unconventional, it sounds awkward even though it’s 100% grammatically valid. We connect other verbs to present-perfect statements all the time (“I seem to have forgotten”; “I expect to have finished it by then”), but with wanting, we force the subsequent statement into the present tense. Why is that?

I notice that saying “I want to have done X” sounds kind of insincere. If you tell me you’re gonna read Paradise Lost just because you “want to have it under [your] belt,” socially that’s kind of weird. It leaves your real motive ambiguous—what exactly are you going to get out of it? Do you need to read it for a class or something? Do you just want to show off on Goodreads?

If you’re reading it without wanting to read it, that implies your heart’s not in it. It implies you’re not really paying attention during the act, you’re just checking a box. It “doesn’t count.” By contrast, when a person acts directly on their desires, it counts: it tells you something about their identity.

And now we’ve answered an important question: Why are you announcing your desires in the first place? Often it’s for the sake of cultivating an identity.

- First, there’s your social identity. You can gain social status by doing things that your peers find interesting or cool—but only if you appear to genuinely want to do them. That way, it makes you the kind of person who does X, rather than just a person who did X. The former is an identity; the latter is just an action with an unclear motive. And if the motive is to gain social status, that makes you a poser, which nobody respects.

- Second, there’s your status in your own eyes—your self-image. Here you’re doing the same kind of performance, but for an audience in your own head. You want to prove to yourself that you’re the kind of person who does X. In general you need to believe good things about yourself.

This move of switching the tenses is very similar to liking the idea of something without liking the thing itself.

I’m so old and i still fail to distinguish wanting to do something from liking the idea of myself doing it

— hyper(bolic) disco(unting) girl (@hyperdiscogirl) August 23, 2024

It’s all about the thing “looking good on paper,” where the paper is an imaginary ledger of all the good and worthy traits you possess.

Some examples

It’s especially funny that the Mark Twain quote is about Paradise Lost, because for a long time I thought I wanted to read the entire The Divine Comedy, which happens to also be an epic poem that was written hundreds of years ago that has themes of Christian theology and that’s now canonized as a great work of Western literature. Mark Twain saw right through me.

The Divine Comedy was on my reading list for years, but I never started reading it; I never felt a desire to start. My real desire was to be familiar with all the compelling imagery in that book, and to feel more legitimate as a lover of the Italian Renaissance, and maybe to hold it as a point of pride that I’m the interesting kind of person who enjoys a 700-year-old giant poem. One day I saw it there on my reading list and realized, “I just want to have read this,” and I deleted it.

I recall having a lot of these false desires during and immediately after college, and I feel like I see college-age people doing it more than others. During college years you’re figuring out your own adult identity while being exposed to all these interesting paths of human endeavor, many of which are considered prestigious and respectable by people you consider prestigious and respectable (namely professors). “How cool would it be if I was a Bach guy?” “How neat would it be if I could speak Mandarin?”

The typical college student’s experience is perhaps the perfect mix of being old enough to charter a course for your life, young enough to not know what you really want in life, wise enough to want to better yourself, and impressionable enough to uncritically adopt someone else’s definition of “better.” You start ardently pursuing the things you “want,” but you don’t realize that those wants are captive to the hidden project of adding shiny badges to your identity.

This also applies to completing things that were fun at first but eventually stopped being worthwhile, where “completion” is a kind of arbitrary label that some people care about for social reasons. For example, you’ve read 10 out of 12 chapters of a nonfiction book, and the other two chapters don’t seem relevant to you. Do you grind through them just so you can say you’ve read the book “cover to cover?” And many modern video games are notoriously annoying to complete to 100%, where the last few goals involve running around a virtual world for hours picking up meaningless collectibles. But are you a “real fan” if you haven’t 100%ed it?

You also see a lot of false desires in influencer/socialite culture. She needs to be at that beach club tonight. Does she want to go? “Of course!” No, she doesn’t. She’s tired and wine-drunk from a day on the boat and she hasn’t eaten enough solid calories today and she’d really feel so much better if she went home. But she wants to have gone to the beach club because that would make it the “perfect day in the Hamptons” and her Instagram stories will be stellar.

I’m not blameless of this either! I’m no influencer but I certainly deal with my own version of “It’ll sound cool to say I’ve done this, so can I just rally and convince myself I want to do it??”

Why is it bad?

We’ve established that this little verb tense switcheroo is a lie, which does suggest it’s bad, but let’s look at the actual harm done.

You have some free time and you think you’re spending it on what you really want, but for some reason it all feels so laborious. Or, for some reason you just aren’t doing it at all.

But you don’t know the reason. So from your view, this is “the thing I want to do.” So you think, “Huh, I really should get around to it.”

Should. Now you’re trying to coerce yourself into doing what you “want.” Aren’t you working enough already? Like for a paycheck? Imagine the mental toll it takes when your “free time” experience is psychologically identical to your day job or schoolwork.

Under these conditions, you never unwind; you never get into a flow state; you never unleash your full creative ability. You’re slaving away in the mines when you could be collecting seashells on the beach.

“But what if I really want what’s in the mines? Sometimes you have to do unpleasant work to get what you want.” Absolutely, but when you’re honest about it, you’ll correctly recognize those situations as life-consuming work, and that’ll affect how you relate to the task. You’ll say, “I want to find three pieces of gold,” instead of saying, “I want to work in the mines.” And so you won’t expect to feel alive or rejuvenated or joyful from the work itself. You’ll recognize it as something you might have to mentally prepare for; something you need to take breaks from, etc. This is related to being a benevolent Manager: assigning your Employee (your future self) only work that is worthwhile. They might be the best Employee, willing to grind for hours and hours on whatever work you put in front of them, but a good Manager won’t take this for granted.

Handling your present perfect tense desires

What do you do once you recognize that your desire to do something is actually a desire to have done it?

Now we’ve landed on a dynamic that I’ve written about before in the much more general case: Symbols and substance.

- Genuine action is the substance: you make art, because you genuinely want to, and therefore you’re an artist. Identity is perfectly entangled with genuine action. You are what you do.

- But having done something is a symbol for that substance. Or, we could say: having the memories/experience of an action is a symbol for having genuinely done it. The genuineness is implied—but of course, that’s where the tricks come in.

You look at a person who taught himself Mandarin, just for fun. For good measure, let’s say he focused like crazy and made significant progress in just one year. You’re impressed. What he did is a testament to his curiosity, intelligence, agency, and other good traits. You want to think of yourself as having those traits. You think about the end-state of being able to speak Mandarin thanks to your own initiative, and you feel good about yourself. So you confuse the symbol for the substance and think, “I want to teach myself Mandarin!” That is Surrogation.

Two months later you realize you’re miserable forcing yourself to learn Mandarin, or you’re just not doing it at all. You only wanted to have learned Mandarin, you didn’t want to learn it. What do you do next? Your different choices parallel the different Responses to surrogation:

Return to the substance

If you really examine your admiration for the Mandarin-learning guy, you’d probably see that it’s not the specific task you admire, but something that it represents. Maybe you feel he has a quality that you’re missing; maybe you want to challenge yourself more. As you get away from the specifics, you find something more general that you truly want.

And then you can find specifics that actually work for you.

Use the symbols as symbols

If you’ve made up your mind to consciously use the symbol to sway your audience, this could work out to give you exactly what you want. But that means you’re hiding information; you’re faking, to some degree, and that’s risky.

Sometimes you just wield the symbols on purpose. You do a thing for indirect reasons—like to own the state of having done it. People will see that you did it and make the expected judgments about your identity. But this is deceptive, because you weren’t genuine.

And also, you can’t lie to yourself if you know it’s a lie. So you’re not going to get the self-image boost you were hoping for. You’ll only get the social status. That sets up a tricky situation where other people’s view of you is systematically more positive than your own view of yourself. And that’s a perfect recipe for insecurity. Authenticity is better in the long run.

Abandon both

Or, you can just drop the whole intention, like I did with The Divine Comedy. Life is short, and you’re allowed to be strict about what you spend time on. Admit you’re not the kind of person who enjoys Paradise Lost, and you can live with that.

If you liked this post, consider subscribing to my personal blog at https://patrickdfarley.com.

Having previously been supremely convinced of this way of thinking by reading The Last Psychiatrist, and having lived by it for the last few years, I do now suspect it’s possible to take it too far.

I think the desire for status - the goal of being able to say and think “I am this type of person”, and be recognized for it - is a part of the motivation system. As you say, some (most?) take it too far. But if one truly excises this way of thinking from themselves, they’ve kind of… excised part of their motivational system!

I think you’ve anticipated this point, because you say

>”But what if I really want what’s in the mines? Sometimes you have to do unpleasant work to get what you want.” Absolutely, but when you’re honest about it, you’ll correctly recognize those situations as life-consuming work, and that’ll affect how you relate to the task. You’ll say, “I want to find three pieces of gold,” instead of saying, “I want to work in the mines.” And so you won’t expect to feel alive or rejuvenated or joyful from the work itself.

But I’m not so sure that replacement maintains the motivation that the identity-based motivation gives. For example, when I was training for and fighting in amateur boxing, I trained and ran all the time. During runs, especially sprinting, where I was tired and wanted to quit, I would say out loud (or even yell) things like “this is easy for me because I’m a fighter!” If I had instead been thinking “this sucks but I have to do it anyway because the payoff is worth it”, that would have felt a good deal less motivating.

Or, I don’t know, maybe in marital and relationship fidelity. I am not a person who cheats; it would be a stain on my soul if I cheated. “I must never be a person who cheats.” This makes it easy to not cheat. This identity-based rule works well for me, and I don’t think replacing it with non-identity thinking would be safe for me personally.

But again I think I do agree! And most normal people would probably be better off from the advice to do more things they want to do, and less things they want to have done. But to readers who have already gone down this road… don’t feel like you need to take it all the way! Preserving some identity-based motivation is good and important.

Great comment, and I will have to think more about this. Your examples do seem to support the utility of self-identity-based motivation.

I think maybe my statement "you can’t lie to yourself if you know it’s a lie" is forcing a frame where self-talk is either a genuine attempt at truth, or a lie. But with "this is easy for me because I’m a fighter" and similar statements, it seems they can be received by the mind in a different way - more like as self-fulfilling prophecy.

I guess it's an open question for me then, where to use that kind of self-talk. On... (read more)