In classical logic, the operational definition of identity is that whenever 'A=B' is a theorem, you can substitute 'A' for 'B' in any theorem where B appears. For example, if (2 + 2) = 4 is a theorem, and ((2 + 2) + 3) = 7 is a theorem, then (4 + 3) = 7 is a theorem.

This leads to a problem which is usually phrased in the following terms: The morning star and the evening star happen to be the same object, the planet Venus. Suppose John knows that the morning star and evening star are the same object. Mary, however, believes that the morning star is the god Lucifer, but the evening star is the god Venus. John believes Mary believes that the morning star is Lucifer. Must John therefore (by substitution) believe that Mary believes that the evening star is Lucifer?

Or here's an even simpler version of the problem. 2 + 2 = 4 is true; it is a theorem that (((2 + 2) = 4) = TRUE). Fermat's Last Theorem is also true. So: I believe 2 + 2 = 4 => I believe TRUE => I believe Fermat's Last Theorem.

Yes, I know this seems obviously wrong. But imagine someone writing a logical reasoning program using the principle "equal terms can always be substituted", and this happening to them. Now imagine them writing a paper about how to prevent it from happening. Now imagine someone else disagreeing with their solution. The argument is still going on.

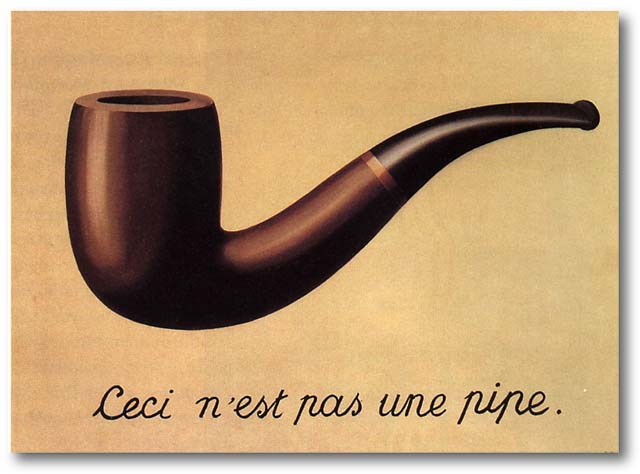

P'rsnally, I would say that John is committing a type error, like trying to subtract 5 grams from 20 meters. "The morning star" is not the same type as the morning star, let alone the same thing. Beliefs are not planets.

morning star = evening star

"morning star" ≠ "evening star"

The problem, in my view, stems from the failure to enforce the type distinction between beliefs and things. The original error was writing an AI that stores its beliefs about Mary's beliefs about "the morning star" using the same representation as in its beliefs about the morning star.

If Mary believes the "morning star" is Lucifer, that doesn't mean Mary believes the "evening star" is Lucifer, because "morning star" ≠ "evening star". The whole paradox stems from the failure to use quote marks in appropriate places.

You may recall that this is not the first time I've talked about enforcing type discipline—the last time was when I spoke about the error of confusing expected utilities with utilities. It is immensely helpful, when one is first learning physics, to learn to keep track of one's units—it may seem like a bother to keep writing down 'cm' and 'kg' and so on, until you notice that (a) your answer seems to be the wrong order of magnitude and (b) it is expressed in seconds per square gram.

Similarly, beliefs are different things than planets. If we're talking about human beliefs, at least, then: Beliefs live in brains, planets live in space. Beliefs weigh a few micrograms, planets weigh a lot more. Planets are larger than beliefs... but you get the idea.

Merely putting quote marks around "morning star" seems insufficient to prevent people from confusing it with the morning star, due to the visual similarity of the text. So perhaps a better way to enforce type discipline would be with a visibly different encoding:

morning star = evening star

13.15.18.14.9.14.7.0.19.20.1.18 ≠ 5.22.5.14.9.14.7.0.19.20.1.18

Studying mathematical logic may also help you learn to distinguish the quote and the referent. In mathematical logic, |- P (P is a theorem) and |- []'P' (it is provable that there exists an encoded proof of the encoded sentence P in some encoded proof system) are very distinct propositions. If you drop a level of quotation in mathematical logic, it's like dropping a metric unit in physics—you can derive visibly ridiculous results, like "The speed of light is 299,792,458 meters long."

Alfred Tarski once tried to define the meaning of 'true' using an infinite family of sentences:

("Snow is white" is true) if and only (snow is white)

("Weasels are green" is true) if and only if (weasels are green)

...

When sentences like these start seeming meaningful, you'll know that you've started to distinguish between encoded sentences and states of the outside world.

Similarly, the notion of truth is quite different from the notion of reality. Saying "true" compares a belief to reality. Reality itself does not need to be compared to any beliefs in order to be real. Remember this the next time someone claims that nothing is true.

I like these posts, but let me add a couple of comments. In philosophical circles the "type distinction", as you call it, is known as the use/mention distinction, i.e. the distinction between using a phrase like "evening star" (to talk about the thing itself) and merely talking about the phrase (usually signaled by quotation marks).

But that's not the first problem you mentioned, which is known in philosophical circles as the failure of substitution in intensional (i.e., roughly, mental) contexts. I'm not so sure the use/mention distinction is useful in explaining this failure. For example, the sentence "Lois is looking for Superman" cannot be substituted for "Lois is looking for Clark Kent", because she may not know that that Superman and Clark Kent are identical. Obviously we never make that mistake, but if someone were to make it, the reason is surely to do with failing to realise that Lois may have false beliefs. But that's not a category mistake.

Really?

What is Lois actually looking for? When we say she's looking for Superman, we mean she's got a search target in her mind, a conceptual representation of Superman, and she's looking for something that matches that target closely enough to satisfy her. (Or, well, we ought to mean that. What we actually mean, I'm less sure of.)

If I introduce the typographical convention to designate a conceptual representation of an object X and the convention m(x) to designate an object that matches a concept x, then Lois is look... (read more)