How often do you make predictions (either about future events, or about information that you don't yet have)? If you're a regular Less Wrong reader you're probably familiar with the idea that you should make your beliefs pay rent by saying, "Here's what I expect to see if my belief is correct, and here's how confident I am," and that you should then update your beliefs accordingly, depending on how your predictions turn out.

And yet… my impression is that few of us actually make predictions on a regular basis. Certainly, for me, there has always been a gap between how useful I think predictions are, in theory, and how often I make them.

I don't think this is just laziness. I think it's simply not a trivial task to find predictions to make that will help you improve your models of a domain you care about.

At this point I should clarify that there are two main goals predictions can help with:

- Improved Calibration (e.g., realizing that I'm only correct about Domain X 70% of the time, not 90% of the time as I had mistakenly thought).

- Improved Accuracy (e.g., going from being correct in Domain X 70% of the time to being correct 90% of the time)

If your goal is just to become better calibrated in general, it doesn't much matter what kinds of predictions you make. So calibration exercises typically grab questions with easily obtainable answers, like "How tall is Mount Everest?" or "Will Don Draper die before the end of Mad Men?" See, for example, the Credence Game, Prediction Book, and this recent post. And calibration training really does work.

But even though making predictions about trivia will improve my general calibration skill, it won't help me improve my models of the world. That is, it won't help me become more accurate, at least not in any domains I care about. If I answer a lot of questions about the heights of mountains, I might become more accurate about that topic, but that's not very helpful to me.

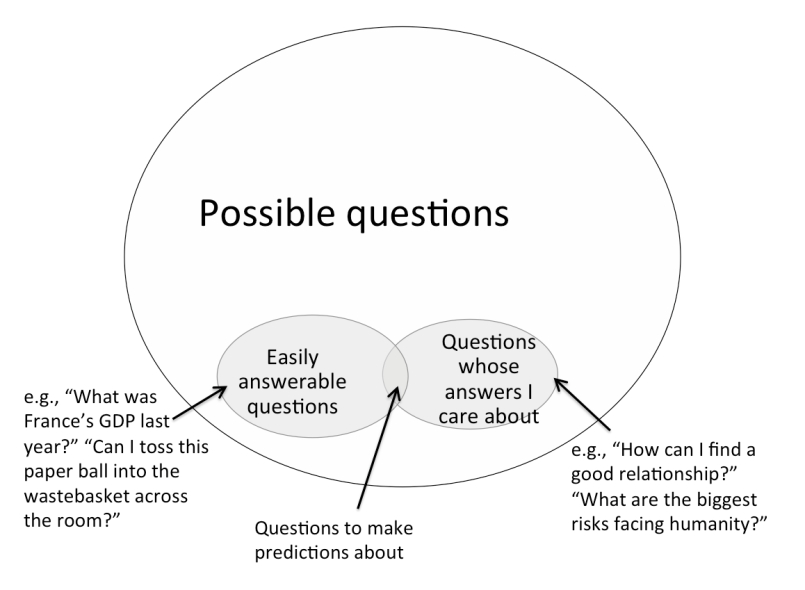

So I think the difficulty in prediction-making is this: The set {questions whose answers you can easily look up, or otherwise obtain} is a small subset of all possible questions. And the set {questions whose answers I care about} is also a small subset of all possible questions. And the intersection between those two subsets is much smaller still, and not easily identifiable. As a result, prediction-making tends to seem too effortful, or not fruitful enough to justify the effort it requires.

But the intersection's not empty. It just requires some strategic thought to determine which answerable questions have some bearing on issues you care about, or -- approaching the problem from the opposite direction -- how to take issues you care about and turn them into answerable questions.

I've been making a concerted effort to hunt for members of that intersection. Here are 16 types of predictions that I personally use to improve my judgment on issues I care about. (I'm sure there are plenty more, though, and hope you'll share your own as well.)

- Predict how long a task will take you. This one's a given, considering how common and impactful the planning fallacy is.

Examples: "How long will it take to write this blog post?" "How long until our company's profitable?" - Predict how you'll feel in an upcoming situation. Affective forecasting – our ability to predict how we'll feel – has some well known flaws.

Examples: "How much will I enjoy this party?" "Will I feel better if I leave the house?" "If I don't get this job, will I still feel bad about it two weeks later?" - Predict your performance on a task or goal.

One thing this helps me notice is when I've been trying the same kind of approach repeatedly without success. Even just the act of making the prediction can spark the realization that I need a better game plan.

Examples: "Will I stick to my workout plan for at least a month?" "How well will this event I'm organizing go?" "How much work will I get done today?" "Can I successfully convince Bob of my opinion on this issue?" - Predict how your audience will react to a particular social media post (on Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, a blog, etc.).

This is a good way to hone your judgment about how to create successful content, as well as your understanding of your friends' (or readers') personalities and worldviews.

Examples: "Will this video get an unusually high number of likes?" "Will linking to this article spark a fight in the comments?" - When you try a new activity or technique, predict how much value you'll get out of it.

I've noticed I tend to be inaccurate in both directions in this domain. There are certain kinds of life hacks I feel sure are going to solve all my problems (and they rarely do). Conversely, I am overly skeptical of activities that are outside my comfort zone, and often end up pleasantly surprised once I try them.

Examples: "How much will Pomodoros boost my productivity?" "How much will I enjoy swing dancing?" - When you make a purchase, predict how much value you'll get out of it.

Research on money and happiness shows two main things: (1) as a general rule, money doesn't buy happiness, but also that (2) there are a bunch of exceptions to this rule. So there seems to be lots of potential to improve your prediction skill here, and spend your money more effectively than the average person.

Examples: "How much will I wear these new shoes?" "How often will I use my club membership?" "In two months, will I think it was worth it to have repainted the kitchen?" "In two months, will I feel that I'm still getting pleasure from my new car?" - Predict how someone will answer a question about themselves.

I often notice assumptions I'm been making about other people, and I like to check those assumptions when I can. Ideally I get interesting feedback both about the object-level question, and about my overall model of the person.

Examples: "Does it bother you when our meetings run over the scheduled time?" "Did you consider yourself popular in high school?" "Do you think it's okay to lie in order to protect someone's feelings?" - Predict how much progress you can make on a problem in five minutes.

I often have the impression that a problem is intractable, or that I've already worked on it and have considered all of the obvious solutions. But then when I decide (or when someone prompts me) to sit down and brainstorm for five minutes, I am surprised to come away with a promising new approach to the problem.

Example: "I feel like I've tried everything to fix my sleep, and nothing works. If I sit down now and spend five minutes thinking, will I be able to generate at least one new idea that's promising enough to try?" - Predict whether the data in your memory supports your impression.

Memory is awfully fallible, and I have been surprised at how often I am unable to generate specific examples to support a confident impression of mine (or how often the specific examples I generate actually contradict my impression).

Examples: "I have the impression that people who leave academia tend to be glad they did. If I try to list a bunch of the people I know who left academia, and how happy they are, what will the approximate ratio of happy/unhappy people be?"

"It feels like Bob never takes my advice. If I sit down and try to think of examples of Bob taking my advice, how many will I be able to come up with?" - Pick one expert source and predict how they will answer a question.

This is a quick shortcut to testing a claim or settling a dispute.

Examples: "Will Cochrane Medical support the claim that Vitamin D promotes hair growth?" "Will Bob, who has run several companies like ours, agree that our starting salary is too low?" - When you meet someone new, take note of your first impressions of him. Predict how likely it is that, once you've gotten to know him better, you will consider your first impressions of him to have been accurate.

A variant of this one, suggested to me by CFAR alum Lauren Lee, is to make predictions about someone before you meet him, based on what you know about him ahead of time.

Examples: "All I know about this guy I'm about to meet is that he's a banker; I'm moderately confident that he'll seem cocky." "Based on the one conversation I've had with Lisa, she seems really insightful – I predict that I'll still have that impression of her once I know her better." - Predict how your Facebook friends will respond to a poll.

Examples: I often post social etiquette questions on Facebook. For example, I recently did a poll asking, "If a conversation is going awkwardly, does it make things better or worse for the other person to comment on the awkwardness?" I confidently predicted most people would say "worse," and I was wrong. - Predict how well you understand someone's position by trying to paraphrase it back to him.

The illusion of transparency is pernicious.

Examples: "You said you think running a workshop next month is a bad idea; I'm guessing you think that's because we don't have enough time to advertise, is that correct?"

"I know you think eating meat is morally unproblematic; is that because you think that animals don't suffer?" - When you have a disagreement with someone, predict how likely it is that a neutral third party will side with you after the issue is explained to her.

For best results, don't reveal which of you is on which side when you're explaining the issue to your arbiter.

Example: "So, at work today, Bob and I disagreed about whether it's appropriate for interns to attend hiring meetings; what do you think?" - Predict whether a surprising piece of news will turn out to be true.

This is a good way to hone your bullshit detector and improve your overall "common sense" models of the world.

Examples: "This headline says some scientists uploaded a worm's brain -- after I read the article, will the headline seem like an accurate representation of what really happened?"

"This viral video purports to show strangers being prompted to kiss; will it turn out to have been staged?" - Predict whether a quick online search will turn up any credible sources supporting a particular claim.

Example: "Bob says that watches always stop working shortly after he puts them on – if I spend a few minutes searching online, will I be able to find any credible sources saying that this is a real phenomenon?"

I have one additional, general thought on how to get the most out of predictions:

Rationalists tend to focus on the importance of objective metrics. And as you may have noticed, a lot of the examples I listed above fail that criterion. For example, "Predict whether a fight will break out in the comments? Well, there's no objective way to say whether something officially counts as a 'fight' or not…" Or, "Predict whether I'll be able to find credible sources supporting X? Well, who's to say what a credible source is, and what counts as 'supporting' X?"

And indeed, objective metrics are preferable, all else equal. But all else isn't equal. Subjective metrics are much easier to generate, and they're far from useless. Most of the time it will be clear enough, once you see the results, whether your prediction basically came true or not -- even if you haven't pinned down a precise, objectively measurable success criterion ahead of time. Usually the result will be a common sense "yes," or a common sense "no." And sometimes it'll be "um...sort of?", but that can be an interestingly surprising result too, if you had strongly predicted the results would point clearly one way or the other.

Along similar lines, I usually don't assign numerical probabilities to my predictions. I just take note of where my confidence falls on a qualitative "very confident," "pretty confident," "weakly confident" scale (which might correspond to something like 90%/75%/60% probabilities, if I had to put numbers on it).

There's probably some additional value you can extract by writing down quantitative confidence levels, and by devising objective metrics that are impossible to game, rather than just relying on your subjective impressions. But in most cases I don't think that additional value is worth the cost you incur from turning predictions into an onerous task. In other words, don't let the perfect be the enemy of the good. Or in other other words: the biggest problem with your predictions right now is that they don't exist.

This is a crucial observation if you are trying to use this technique to improve your calibration of your own accuracy! You can't just start making bets when no one else you associate regularly is challenging you to the bets.

Several years ago, I started taking note of all of the times I disagreed with other people and looking it up, but initially, I only counted myself as having "disagreed with other people" if they said something I thought was wrong, and I attempted to correct them. Then I soon added in the case when they corrected me and I argued back. During this period of time, I went from thinking I was about 90% accurate in my claims to believing I was way more accurate than that. I would go months without being wrong, and this was in college, so I was frequently getting into disagreements with people, probably, an average, three a day during the school year. Then I started checking the times that other people corrected me, just as much as I checked when I corrected other people. (Counting even the times that I made no attempt to argue.) And my accuracy rate plummeted.

Another thing I would recommend to people starting out in doing this is that you should keep track of your record with individual people not just your general overall record. My accuracy rate with a few people is way lower than my overall accuracy rate. My overall rate is higher than it should be because I know a few argumentative people who are frequently wrong. (This would probably change if we were actually betting money, and we were only counting arguments when those people were willing to bet. So you're approach adjusts for this better than mine.) I have several people for whom I'm close to 50%, and there are two people for whom I have several data points and my overall accuracy is below 50%.

There's one other point I think somebody needs to make about calibration. And that's that 75% accuracy when you disagree with other people is not the same thing as 75% accuracy. 75% information fidelity is atrocious; 95% information fidelity is not much better. Human brains are very defective in a lot of ways, but they aren't that defective! Except at doing math. Brains are ridiculously bad at math relative to how easily machines can be implemented to be good at math. For most intents and purposes, 99% isn't a very high percentage. I am not a particular good driver, but I haven't gotten into a collision with another vehicle in my well over 1000 times driving. Percentages tend to have an exponential scale to them (or more accurately a logistic curve). You don't have to be a particularly good driver to avoid getting into an accident 99.9% of the time you get behind the wheel, because that is just a few orders of magnitude improvement relative to 50%.

Information fidelity differs from information retention. Discarding 25% or 95% or more of collected information is reasonable; corrupting information at that rate is what I'm saying would be horrendous. (Because discarding information conserves resources; whereas corrupting information does not... except to the extent that you would consider compressing information with a lossy (as in "not lossless") compression to be a corrupting information, but I would still consider that to be discarding information. Episodic memory is either very compressed or very corrupted depending on what you think it should be.)

In my experience, people are actually more likely to be underconfident about factual information than they are to be overconfident, if you measure confidence on an absolute scale instead of a relative-to-other-people scale. My family goes to trivia night, and we almost always get at least as many correct as we expect to get correct, usually more. However, other teams typically score better than we expect them to score too, and we win the round less often than we expect to.

Think back to grade school when you actually had fill in the blank and multiple choice questions on tests. I'm going to guess that you probably were an A student and got around 95% right on your tests... because a) that's about what I did and I tend to project, b) you're on LessWrong so you were probably an A student, and C) you say you feel like you ought to be right about 95% of the time. I'm also going to guess (because I tend to project my experience onto other people) that you probably felt a lot less than 95% confident on average when you were taking the tests. There were more than a few tests I took in my time in school where I walked out of the test thinking "I didn't know any of that; I'll probably get a 70 or better just because that would be horribly bad compared to what I usually do, but I really feel like I failed that"... and it was never 70. (Math was the one exception in which I tended to be overconfident, I usually made more mistakes than I expected to make on my math tests.)

Where calibration is really screwed up is when you deal with subjects that are way outside of the domain of normal experience, especially if you know that you know more than your peer group about this domain. People are not good at thinking about abstract mathematics, artificial intelligence, physics, evolution, and other subjects that happen at a different scale from normal everyday life. When I was 17, I thought I understood Quantum Mechanics just because I'd read A Brief History of Time and A Universe in a Nut Shell... Boy was I wrong!

On LessWrong, we are usually discussing subjects that are way beyond the domain of normal human experience, so we tend to be overconfident in our understanding of these subjects... but part of the reason for this overconfidence is that we do tend to be correct about most of the things we encounter within the confines of routine experience.