[as requested reposted in this thread]

On noticing distractions, meditation practice, esp. the Buddhist one based on the Pali Canon has some interesting concepts that you may find interesting:

Subtle Distraction (sukhuma vicāra) is a nuanced mental activity that doesn't completely pull attention away from the meditation object but dilutes the focus. It is the hardest to notice until mastering mindfulness (sati) and clear comprehension (sampajañña). Note that vicāra translates to applied thought or examination and refers to the attention on something else.

Gross Distraction (oḷārika vicāra) is the distraction we sometimes catch, e.g., when we notice that we skipped a sentence in a book, and then return to the text. It is the mind's tendency to engage with sensory or mental phenomena that significantly divert attention away from the object, esp. the often comparatively boring meditation object.

Forgetting (vicikicchā or musitasmim) happens when we lose the (meditation) object from our attention altogether. Only a while later we realize that we are still holding the book or sitting on our pillow. Musitasmim translates to forgetting or negligence - the object has slipped from short-term memory by not concentrating. Another term, vicikicchā means doubt, which indicates that the purpose of our action was not strong enough to motivate us and we - at least subconsciously - doubted the value.

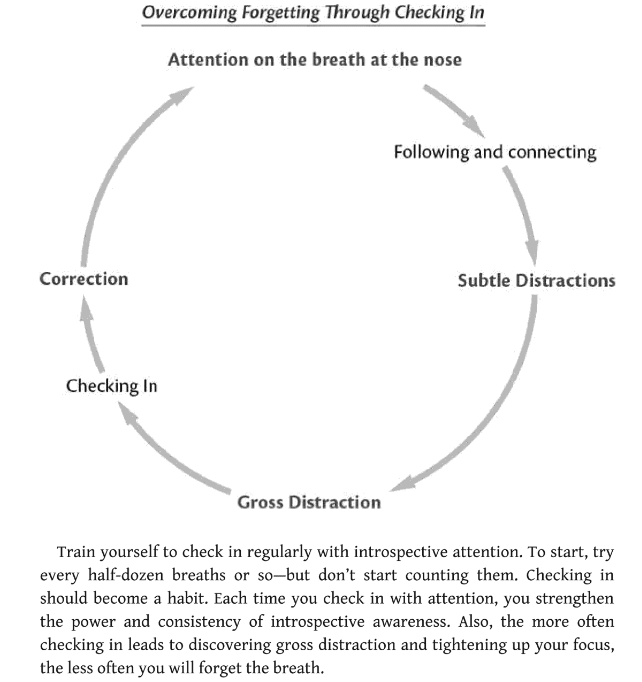

In The Mind Illuminated, dealing with these levels of distraction is a core aspect of the early levels of meditation practice. Here is an illustration from the book:

There are forums online that discuss the practice of noticing distractions based on the book. Here is one random example.

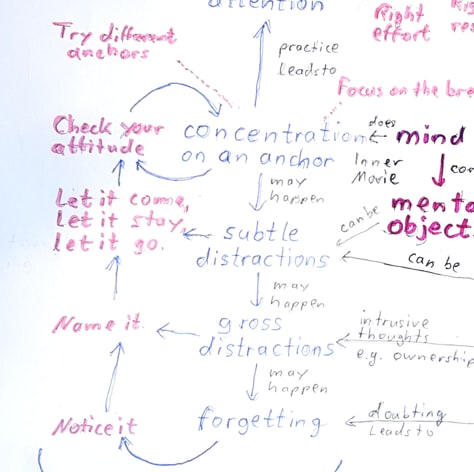

Here is the part of my notes from meditation retreats in 2019 and 2022 that summarizes the practice of concentration meditation and dealing with distractions - in a short Sazen: Notice, name, accept, and return to the object.

This is the third post in a sequence that demonstrates a complete naturalist study, specifically a study of query hugging (sort of), as described in The Nuts and Bolts of Naturalism. This one demos phases one and two: Locating Fulcrum Experiences and Getting Your Eyes On. For context on this sequence, see the intro post. If you're intimidated by the length of this post, remember that this is meant as reference material. Feel free to start with "My Goals For This Post", and consider what more you want from there.

Having chosen a quest—”What’s going on with distraction?"—my naturalist study began in earnest.

In "Nuts and Bolts of Naturalism", the first two phases of study that I discussed after "Getting Started" were "Locating Fulcrum Experiences" and "Getting Your Eyes On". In practice, though, I often do a combination of these phases, which is what happened this time. For the sake of keeping track of where we are in the progression, I think it's best to think of me as hanging out in some blend of the early phases, which we might as well call "Locating Your Eyes".

My Goals For This Post

Much of the “learning” that happens in the first two phases (or "locating your eyes") could be just as well described as unlearning: a setting aside of potentially obfuscatory preconceptions. My unlearning this time was especially arduous. I was guided by a clumsy story, and had to persist through a long period of deeply uncomfortable doubt and confusion as I gradually weaned myself off of it.

It took me a long time to find the right topic and to figure out a good way into it. If this were a slightly different sort of essay, I'd skip all of the messiness and jump to the part where my progress was relatively clear and linear. I would leave my fumbling clumsiness off of the page.

Instead, I want to show you what actually happened. I want you to know what it is like when I am "feeling around in the dark” toward the beginning of a study. I want to show you the reality of looking for a fulcrum experience when you haven’t already decided what you’re looking for. Because in truth, it can be quite difficult and discouraging, even when you’re pretty good at this stuff; it's important to be prepared for that.

So I want you to see me struggle, to see how I wrestle with challenges. In the rest of this post, I hope to highlight the moves that allowed me to successfully progress, pointing out what I responded to in those moments, what actions I took in response, and what resulted.

To summarize my account: I looped through the first two phases of naturalism a few times, studying “distraction”, then “concentration”, then “crucialness”, before giving up in despair. Then I un-gave-up, looped through them once more with “closeness to the issue”, and finally settled on the right experience to study: a sensation that I call “chest luster”.

To understand this account as a demonstration of naturalism, it’s important to recognize that every loop was a success, even before I found the right place to focus. When studying distraction and concentration, I was not really learning to hug the query yet; but I was learning to perceive details of my experience in the preconceptual layer beneath concepts related to attention. Laying that foundation for direct contact was valuable, since "hug the query” is a special way of using attention.

I will therefore tell you about each loop. I recommend reading through the first loop (“Distraction”) even if you're skipping around, since it includes some pretty important updates to my understanding of the naturalist procedure.

Distraction

I realized during this study that there are a couple crucial distinctions related to fulcrum experiences that I failed to make clearly in the Nuts and Bolts sequence. They’re important to understanding why I proceeded as I did, so here’s a note about them. (This one is less skippable than the others.)

Imagine you want to study newts, and you know that they gather to breed in a certain pool for a few days each spring. You have the pool marked on your map as “breeding pool”, so you know that to study the newts, you should navigate to the breeding pool.

Neither the spot marked “breeding pool” on your map, nor the breeding pool itself, is the creature you want to study. What you’re after are experiences of newts. The map is a tool for finding the pool, and the pool is the physical location of the newts.

Now imagine a slightly different scenario: Through your ecological studies, you’ve inferred that there must be some sort of predator occupying a certain niche; the seasonal fluctuations in the local population of worms and mollusks doesn’t make sense without it. You want to study whatever’s causing the fluctuations.

You do not know that you’re looking for “newts”. In fact, you’ve never even heard of a newt. All you know is that there’s something going on with the worm and mollusk populations, and some sort of amphibian predator is probably responsible.

Again, the experiences you need to have if you want to really learn something are experiences of newts. But given that you don’t even have a concept of newts, your best bet for running into those experiences is to wade into a likely breeding pool, and then to just start looking around for anything that might enjoy eating worms and mollusks.

The fulcrum experience here is probably something like the spotted pattern on a newt’s skin; those spots are among the ways that Eastern spotted newts impinge upon human perceptions.

The fulcrum experience is not “breeding pool”, because that is a label on a map, not a way that something impinges on human perception. Nor is the fulcrum experience “the wetness of water on my legs”, because that is how water impinges on human perception, not how newts do.

However, “the wetness of water on my legs” is an intermediate step between the concept of a breeding pool and the fulcrum experience of spots; a step which I have not named before now, so unfortunately I think I need to invent some new terminology.

I worry that this all sounds a bit tedious, but this framework is probably as close as I’ve so far come to explaining how exactly naturalism manages to repair broken concepts from the bottom up. If your concepts are broken, then your conceptual pointer will almost certainly not lead you directly to a fulcrum experience. But if you can get the hang of identifying crucial conceptual pointers, then it may lead you to a correlated experience, some set of sensations that is frequently present when a novel observation is in principle available to you. Once you’re in the right place and becoming sensitive to experiences, rather than merely employing concepts, there is hope.

Ok, now let’s match up the pieces of that analogy with the strategy in my own study.

I articulated a story during Catching the Spark that “I leave behind distraction when I look toward what is crucial.” The concept of “distraction” that I employ in that sentence is a conceptual pointer, like a dot on the map labeled “breeding pool” in the analogy above. It is not an experience of distraction itself (just as the dot on the map is not full of water).[1]

What the conceptual pointer points toward is experiences of distraction, which may or may not be correlated with some kind of fulcrum experience for this study.

Even if I had correctly identified a closely correlated experience when I chose to focus on “distraction”, experiencing distraction would be like experiencing the wetness of water on your legs while wading into a breeding pool. Wet legs is a sign you’re in the right place, but the fulcrum experience itself will turn out to be the spotted pattern of a newt’s skin.

What would my fulcrum experience be? I did not know yet. I only suspected that I might be able to find it somewhere around experiences of distraction.

And so I studied distraction, asking myself, “Where would I go to find an experience of distraction?”

I thought that I might find distraction during goal-directed behaviors: attempts to accomplish things or to solve problems. So I tried solving a problem from Thinking Physics, specifically “Steam Locomotive”.

This is where the field version of “locating fulcra” began to blend with “getting your eyes on”. I was trying to get my eyes on about distraction, even though distraction indicates a possible location of fulcrum experiences, rather than a fulcrum experience itself.

Why do this? Because I needed reference experiences so that I could narrow in on a fulcrum experience.

(Reminder: A reference experience is a situation you can walk through in your mind, and use as reference material for making guesses. I introduced this term under "Guessing Which Observations Will Matter" in "Locating Fulcrum Experiences.")

In the offline version of fulcrum location, you consult memory and imagination, hoping to retrieve previously-stored information that will help you find a fulcrum experience. If I’d done this offline, I might have called to mind a memory of being distracted, and asked myself, “What exactly was that like? And what parts of that experience seem particularly relevant to this query-hugging thing I’m interested in?”

Instead, I taught myself to pay attention to distraction, so that I could watch for anything that might be relevant as distraction was happening.

Often, doing this online is more efficient than doing it offline, even though it’s a little tricky to describe, and can take a while to get the hang of. If I did find something relevant in the middle of an experience of distraction—similar to seeing something spotted and slithery while first wading into the newt pool—I’d immediately be able to pivot my attention, and I might collect a lot of detail on a fulcrum experience right away.

So I tried to solve “Steam Locomotive”, and I watched for times when I might be “distracted”.

I found that it was not at all obvious most of the time whether I was or was not distracted. This is a common finding in a naturalist study. Concepts tend to abstract the properties of paradigmatic examples of things, but paradigmatic examples are pretty rare in concrete experience. “World is crazier and more of it than we think,” as MacNeice put it.

An excerpt from my log[2] (skip to avoid mild Thinking Physics spoilers):

I learned from this exercise that “avoiding” and “circumnavigating” are things attention can do that is different from “obviously not being distracted”.

Thinking Physics is a great lab setup for this sort of thing, but I was learning in the field as well.

Over the following few days, I collected several field notes. Most of them involve looking at an experience and going, "Is this distraction?" or "What is up with this?"

For example:

This may look like I was mainly trying to improve my map around “distraction”. In a sense I was; but that activity was only instrumental. I was really trying to get in more direct contact with the underlying territory. The explicit map was not the point[3]. The point was the experiences, and my ability to be reflectively aware of their details.

It’s like I’d used my map to navigate to roughly the area of the newt pool, but it was dark out and I couldn’t see very well, and also it turned out that there wasn’t so much a pond as an especially swampy depression in the forest floor. So I was feeling around and going, “Is this the pool? Perhaps it’s a random puddle? What about this soaked bit of moss? What about this wet rock?” and I was updating my map as I went. I didn’t really care whether a given experience “counts as distraction”. I was just trying to get in touch with whatever was going on in the territory in the general vicinity of distraction.

I continued to observe distraction in this way for about two weeks, at which point I felt it was time for my first analysis session. I looked through all the lab notes and field notes I'd collected so far, held them up against my most recent story statement, and asked myself what comes next.

In response to my observations, I articulated a revised story of distraction. Here's what I wrote.

(It did.)

As a result of these reflections, I decided to move my investigation away from "distraction" and toward "concentration", which I hoped would give me another perspective on "distraction" by highlighting the negative space.

Let’s pause to review this loop through the early phases of study. What was it? What happened during it, and why?

Because it was a load-bearing piece of my story (“I leave behind distraction when I look toward what is crucial,”) I treated “distraction” as a conceptual pointer, an idea that could lead me to concrete experiences that might coincide with something important.

I had ideas about what “distraction” was, and these ideas helped me encounter concrete experiences of distraction. I looked for those experiences in a session of lab work, where I tried to solve a problem from Thinking Physics, suspecting that distraction might show up during problem solving. I also watched for experiences of distraction as I went about my days, constantly “tilting my head” or boggling at distraction (in CFAR parlance), and I found myself revising my understanding of what distraction is and how it works.

After I’d collected notes and observations for a while, I did an analysis session to figure out what I should do next. Reviewing my notes, I realized that I wanted to see distraction from another angle, specifically to examine the negative space around it. Toward that end, I chose to begin studying “concentration”.

Concentration

In retrospect, I think my decision to study “concentration” was overly mechanical. One of my heuristics is, “When you feel a little lost, sometimes it helps to try studying the opposite thing,” and that’s what happened here.

Ideally, decisions drawn from reorientation sessions “come from my core”—from an integrated sense of purpose and quality; from vision. What I actually did was more like reaching into the grab bag of mathematical tools during a math exam in high school and “applying the quadratic formula” because you know how to do that, even if you lack any particular sense that it will help.

This decision to study "concentration" came not so much from vision, as from a feeling of pressure to do something legible because I was being watched (by you, through this essay). I made it with a sort of flailing motion. This was inefficient, but it didn’t break anything in the end.

Much as with “distraction”, I used “concentration” as a conceptual pointer. I set out to sink my attention into the details of experiences related to my concept of concentration, using both lab work and field work.

In my first session of lab work, I wanted to really isolate the experience of concentration, to capture it on a slide beneath a microscope. I wanted to know, "What does concentration feel like, all on its own? When I try to concentrate, what motions do I make, and what results?" So I tried a kind of mental exercise that was new to me, one that (as I understand it) consists of basically nothing but concentration: candle gazing. I set out to "concentrate" for one hour on the flame of a candle.

To my surprise, it turned out that my eyes did not leave the candle flame for the entire hour. But of course, there is more to concentration than physically staring.

One thing I found is that concentration seems to exist by degrees. I can concentrate better or worse, but while there might be some threshold beyond which I would describe myself as “concentrating”, that point seems pretty arbitrary.

What was it for a strategy to “work”? What was my perception of “successful concentration” made of?

I’d describe it as the size and frequency of fluctuations in the direction of my attention. If something “new” was in the spotlight—a fragment of song, the motion of my shoulder, etc.—then my attention had moved, and I perceived myself to be concentrating “les” than otherwise. The purpose of the candle flame (I discovered) was to provide a point of comparison. I started out focused on the candle, and I returned my attention to the candle at every opportunity, so I knew that if whatever was in my attention was not the candle, something had changed—my concentration had lapsed.

I also found that several tactics occurred to me, on the spur of the moment, when I wanted to “concentrate better”. Among the apparently less effective methods was brute force: exerting a top-down pressure to banish non-candle mental motions. Even when I was successful, it felt like holding a beach ball underwater.

An enjoyable but fairly ineffective method was to imagine sending my thoughts toward the flame to be burned up by it. I spontaneously “felt” this process pretty vividly, in a tactile sort of way, but my attention didn’t seem to stabilize much afterward.

Although I didn't have great control over it, the most effective deliberate strategy seemed to be variations on "relaxing into the flame". Relaxing my mind in an opening way caused a lot of drifting, but pouring myself like a liquid toward the single point of the flame worked pretty well.

What resulted from an extended period of pure concentration? One thing that resulted was a pretty intense aversion to attempting to write about it! There was a kind of inertia, and I did not want to move my mind around to find words and record observations. I’m glad I wrote about it anyway, because forming long-term memories is apparently incompatible with candle gazing, since any kind of memory encoding process is not the candle flame.

But also, I do think I became much more familiar with the phenomenology of concentration, which would be quite useful to me should concentration turn out to be important to my study.

The next day, I attempted the very same exercise, this time using a math textbook instead of a candle flame. I’d now be concentrating “in practice”, so to speak; for a purpose, rather than in isolation.

The book I used was Terence Tao's Real Analysis I. I wasn't quite sure what "concentrating on the book" would really turn out to entail; but my framework for the physical activity was to set a timer, open the book, point my eyes at the pages, and "do nothing else" until the timer went off, just like with the candle.

There were a few moments I thought might be "lapses in concentration". At one point I heard someone calling, but concluded they were not talking to me and turned back to the book. A few times I "failed to process" the words I'd just read, for various reasons. And at one point I decided to skip half a chapter; I couldn't quite work out the relationship between this decision and concentration.

What was my experience of "successful concentration" like, in the context of reading the textbook?

Unlike with the candle, I spent more time "successfully concentrating" than not, but much of it had a "forced" quality: I had to do something active that often felt a bit like shoving my mind through a straw.

It was also a lot like aiming an arrow. In my notes, I wrote

On the third day, I intended to merely repeat the previous exercise, “reading the textbook. There was a lot more textbook to read, after all. I figured I might as well gather some more data.

However, I was dissatisfied right at the start by a certain definition as presented. I instead spent the whole hour attempting to make a definition I preferred. This involved sketching a logical framework and then trying to express some things formally.

This time, I think my log describes a paradigmatic instance of flow. An excerpt:

I was surprised by the variety of experiences that my idea of “concentration” pointed me toward. Sometimes it was easy, and sometimes it was hard. Sometimes it hurt, and sometimes it felt wonderful. Sometimes it was hard to start, and sometimes it was hard to stop. The nature of the object of my focus seemed to matter a lot.

All of this was interesting to me, but I couldn’t tell whether any of it mattered.

My focus on "concentration" only lasted a few days. It did not feel on track to me, and in fact I was starting to feel pretty lost and sort of scared about it. In such situations, I often do a reorientation session, even if little time has passed. That’s what I did here.

I was in a fair bit of conflict with myself over this decision, a conflict I was only gradually learning to see.

Part of me wanted to focus narrowly on investigative avenues informed by my pre-existing understanding of “hug the query”; let’s call that the “Keep It Simple, Stupid” faction. The KISS faction said things like, “It’s really not that complicated. This is an easy skill. Just list some questions and practice hugging them. You’ll be done in no time, and then you can publish something short and straightforward whose value people will easily recognize.” It also said, “You’re going to look really silly for not just doing the simple obvious things.”

I think KISS was basically correct in its claims. The skill Eliezer advocates in "Hug the Query" is pretty simple. It is roughly, “When evaluating evidence, do not ignore the fact that once you account for the cause of a correlation, the observed variables no longer provide information about each other.”

Even back then, I would probably have been capable of designing exercises that target application of this concept in decision making. That is exactly the sort of thing CFAR units are made of, and it is absolutely a worthwhile type of activity.

However, I could feel the desperation for closure underneath these arguments. I wanted to be done hanging out in all of this uncomfortable uncertainty. I wanted to make sense of things, once and for all. To have answers, especially answers I could cleanly communicate to others.

With respect to the intuitions and curiosities that had led me to investigate “hug the query” in the first place, there was no end in sight, and I felt there might never be. It would be easier, it would be vastly more comfortable, to answer a smaller question than the one I actually cared about.

I knew better than to trust motivations of that flavor, at least in the middle of a naturalist study. And so I continued trying to follow the felt senses that had drawn me to Hug the Query”, the ones I tried to articulate in the story, “I leave behind distraction when I look toward what is crucial.” And I began to study “crucial”.

Crucial

In my third loop through Locating Fulcrum experiences and Getting Your Eyes On, my conceptual pointer was “crucial”, as used in the story, “I leave behind distraction when I look toward what is crucial.”

This time, I sought a reference experience by consulting the present moment.

Reflecting on this excerpt from the other end of my study, I recognize this as a key moment. The fulcrum experience I would eventually focus on is present here, especially in the perception of “things turn on this”. There’s an intersection between “things that are hooked up to the gears of the world” and “things that I actually care about”; membership in that intersection is what I perceived when I glanced at the book, and “things turn on this” was my way of describing it at the time.

Back then, I didn’t know enough to see how important this moment was. I was still swamped with the dizzy disorientation and doubt that had been building for weeks. I was on the right track, but it still felt a lot like a shot in the dark.

So I watched for more instances of this experience, though in a sort of half-hearted way, as I continued to feel pretty lost. Nevertheless, in what field notes resulted, it’s now clear to me that I was honing in on the heart of my study.

Here is a note from September 12th (I had continued to learn real analysis):

There’s little phenomenology captured in that note—no more clues about how something important may be impinging on my perception—but it is a member of the intersection I talked about before. The proof “turns” on “does not equal”.

I was also beginning, at this point, to pay closer attention to the kinds of phenomena that can be fulcrum experiences—the immediate sensations that are more basic than situations or concepts—and so I was moving closer to "getting your eyes on".

I’d just read a demonstration of a mistake students commonly make in mathematical proofs. The mistake in question was mixing up the antecedent and the consequent, which I realized I might very well do when flailing in the presence of algebraic expressions. I snapped my fingers, and then wrote the following (bold added afterwards for emphasis.)

Compare this note to the previous one. Notice me slowing down in the middle of this note.

In the previous note (the one about proving that 4≠0), I was largely conceptualizing. I told a story about why the experience impacted me however it did, rather than digging into the immediate sensations and trying to capture the impact itself. Here, I stopped in the middle of my story telling, and devoted all of my attention to observing whatever sensations were present. That is the gold standard for phenomenological photography.

During my next analysis session, I picked out that note as my favorite so far.

This was among the most pivotal moments in my study. Here, I expressed the idea of “the sensations that get covered up when we don’t attend to what is crucial”. I wasn’t clear on what the crucial sensations were, but I had begun to suspect that they were often “covered up” in some way, and that they might correspond to “a feeling of something being important”.

The Study So Far

Can you feel the oscillating rhythm in my scope? I capture the details of immediate experience, and then much later on I look back at that data and start trying to make sense of it. I zoom in, then I zoom out, then I zoom in again.

I do my best not to demand that my observations make sense to me (or to you) while I make them. That way I can eventually fit my sense-making processes to the data, instead of the other way around.

This oscillation is at the heart of my method. I paint constellations after I have looked at the stars themselves, not in the middle of my attempts to see them.

Sometimes people are surprised and confused when I make a big deal about "directly observing the world", only to spend most of my time focused on stuff that exists inside of minds (such as "distraction").

It is more difficult to see the difference between a concept of distraction and an instance of distraction than to see the difference between the concept of a pool and an instance of a pool. Yet an instance of distraction is a different kind of thing than a concept of distraction, even though both exist inside of minds. In the case of pools, it is relatively easy to know when you have merely activated a concept, and not directly observed an instance. In the case of distraction, it is not so easy. It takes greater skill.

I talk so much about the insides of minds largely because this is when the skills are especially needed.

Instances of distraction may not be part of the "external world" in the sense of existing outside of minds, but they are part of the external world in the sense of existing outside of maps.

You can read my log in its entirety here, if you want to see exactly how I contended with this problem.

Not that explicit maps are ever the point, even for professional cartographers. Maps are for things. I recognize this. But they're for predicting future experiences or something, and that was not the point here either.

From "Locating Fulcrum Experiences":

"I often check how fulcrum-y a certain experience seems by using it to fill in the exclamation, "If only I really understood what was happening in the moments when __!" For example, “If only I really understood what was happening in the moments when I’m attempting to relieve psychological discomfort!” When I’ve chosen a really fulcrum-y sort of experience, completing that sentence tends to create a feeling of possibility; sometimes it's almost like a gigantic tome falling open. Not always, but often."