What would you do and say if you were in Amodei's position?

One indirect piece of evidence is an anecdote recounted by Thomas Shelling in the preface to the 1980 edition of The Strategy of Conflict. The anecdote suggests that we may overestimate people’s familiarity with seemingly obvious concepts.

The book has had a good reception, and many have cheered me by telling me they liked it or learned from it. But the response that warms me most after twenty years is the late John Strachey’s. John Strachey, whose books I had read in college, had been an outstanding Marxist economist in the 1930s. After the war he had been defense minister in Britain’s Labor Government. Some of us at Harvard’s Center for International Affairs invited him to visit because he was writing a book on disarmament and arms control. When he called on me he exclaimed how much this book had done for his thinking, and as he talked with enthusiasm I tried to guess which of my sophisticated ideas in which chapters had made so much difference to him. It turned out it wasn’t any particular idea in any particular chapter. Until he read this book, he had simply not comprehended that an inherently non-zero-sum conflict could exist. He had known that conflict could coexist with common interest but had thought, or taken for granted, that they were essentially separable, not aspects of an integral structure. A scholar concerned with monopoly capitalism and class struggle, nuclear strategy and alliance politics, working late in his career on arms control and peacemaking, had tumbled, in reading my book, to an idea so rudimentary that I hadn’t even known it wasn’t obvious.

The problem is that organizations generally do not include the article used to refer to them in their names. For example, the name of the Council on Foreign Relations is not ‘The Council on Foreign Relations’, but ‘Council on Foreign Relations’. For this reason, one should always use the definite article ‘the’ to refer to CFAR, because one’s intention is to refer to the entity so named. Saying “a Center for Applied Rationality” would invite questions like, “Wait! Are there other orgs also called ‘Center for Applied Rationality’?”

Alternatively, you could change ‘Center for Applied Rationality’ to ‘A Center for Applied Rationality’, but this would also be very strange. As mentioned, entities do not generally include the article as part of their names, but when they do, it is, to my knowledge, always the definite article (e.g., The New York Times).

My humble advice is to drop this idea. You can communicate that you are not trying to be the one canonical org on this topic in other ways.

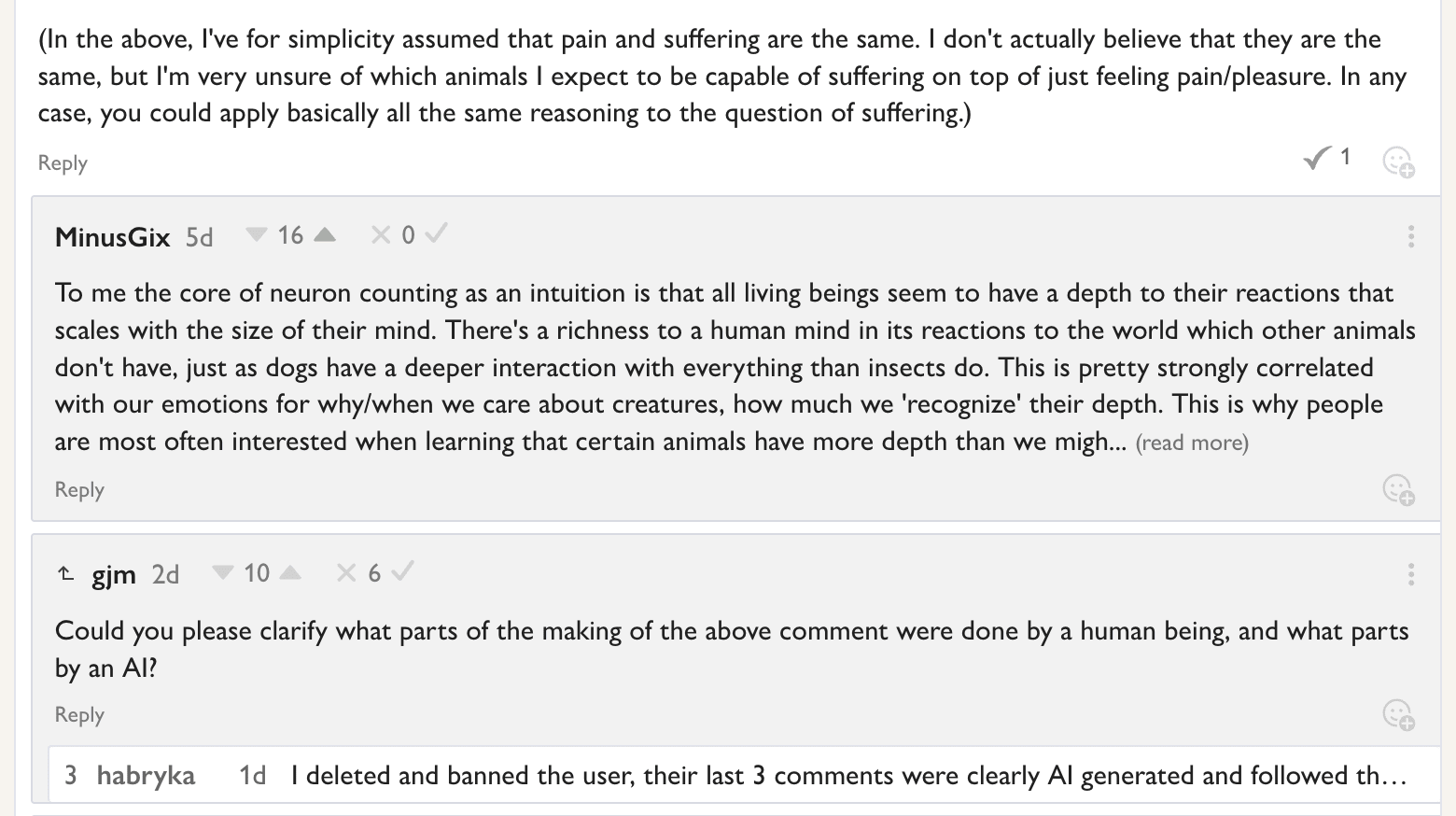

Meta: gjm’s comment appears at the same level as comments that directly reply to Kaj’s original shortform. So until I read your own comment, I assumed they, too, were replying to Kaj. I think deleting a comment shouldn't alter the hierarchy of other comments in that thread.

I think there is a vast difference between Gerard and Kruel, not just in the damage each has caused but also in their intellectual honesty and responsiveness to argument (null in the case of Gerard, decent in the case of Kruel, at least from my recollection).

One of the biggest online threats to rational discourse, “RationalWiki”, just reached a settlement with all but one of the eight plaintiffs suing them, and deleted the corresponding biographical entries. They are also considering pre-emptively removing all their other hit pieces—countless articles that have ruined careers, stifled research, and brought entire fields of inquiry into undeserved disrepute.

I agree this looks promising and is the reason I bought long-dated SPY calls a few weeks ago (already up by 30%). But I would feel more reassured if I felt I could understand why such an opportunity persists. What is the mental state of the person on the other end of this trade?

Can you share the spreadsheet/code on which the calculations are based?

Yeah, that makes sense, especially if combined with the feature that allows users to disagree with specific parts of the post, as Michael notes. (Though note that the disagree vote is anonymous, whereas disagreeing with a selection is public, so the two aren’t fully comparable.)

What Amodei actually says:

The “science-fiction stories involving AIs rebelling against humanity” is included as part of a long list of hypothetical scenarios meant to motivate the claim that an AI existential catastrophe may occur in the absence of power-seeking behavior:

It is very strange to characterize this passage as offering an “amazing improved steel man, which basically is it might watch terminator or read some AI takeover story and randomly decide to do the same thing”, especially when Amodei explicitly writes that “We don’t need a specific narrow story for how it happens”!