Vanessa and diffractor introduce a new approach to epistemology / decision theory / reinforcement learning theory called Infra-Bayesianism, which aims to solve issues with prior misspecification and non-realizability that plague traditional Bayesianism.

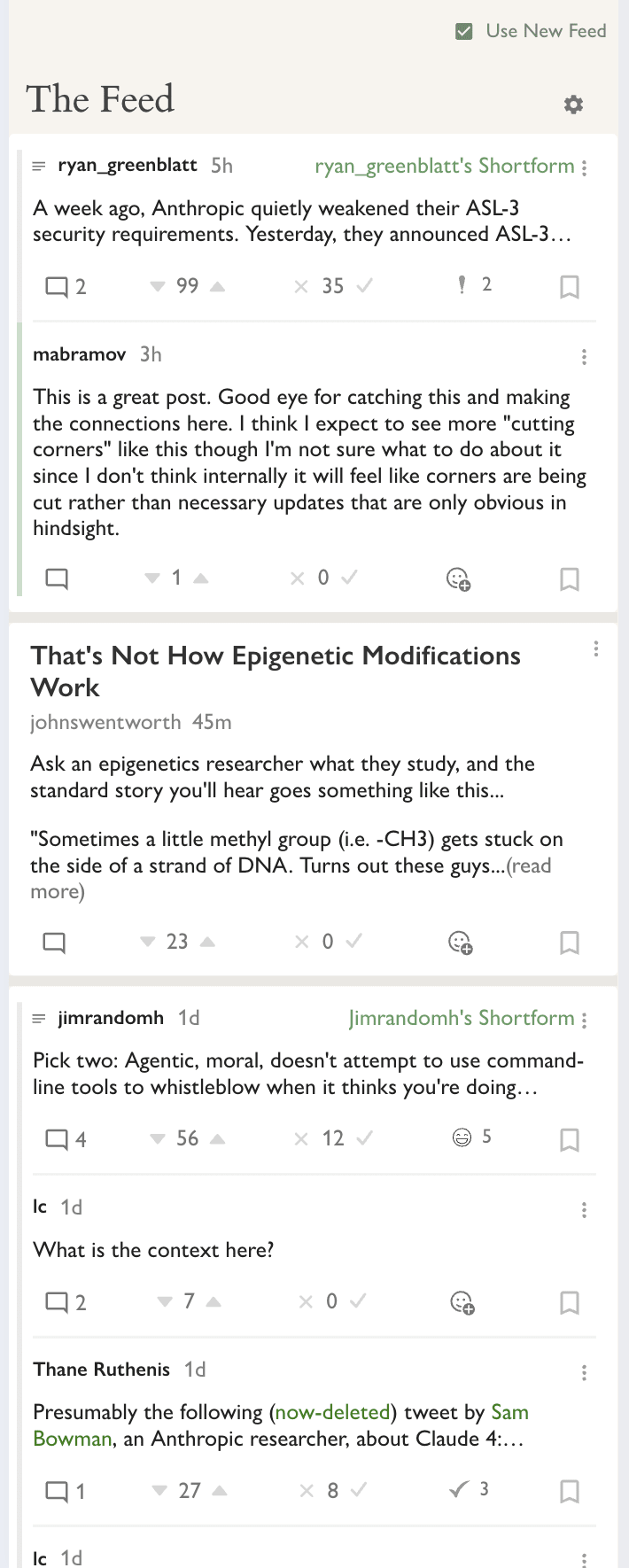

The modern internet is replete with feeds such as Twitter, Facebook, Insta, TikTok, Substack, etc. They're bad in ways but also good in ways. I've been exploring the idea that LessWrong could have a very good feed.

I'm posting this announcement with disjunctive hopes: (a) to find enthusiastic early adopters who will refine this into a great product, or (b) find people who'll lead us to an understanding that we shouldn't launch this or should launch it only if designed a very specific way.

From there, you can also enable it on the frontpage in place of Recent Discussion. Below I have some practical notes on using the New Feed.

Note! This feature is very much in beta. It's rough around the edges.

I've tried to get used to it, but it still feels significantly worse to me. Not quite sure why, I think the UI feels a bit busier which is part of it, but I think it's mainly because it feels like it's trying to control what I see in a way I don't like.

Everyone should do more fun stuff![1]

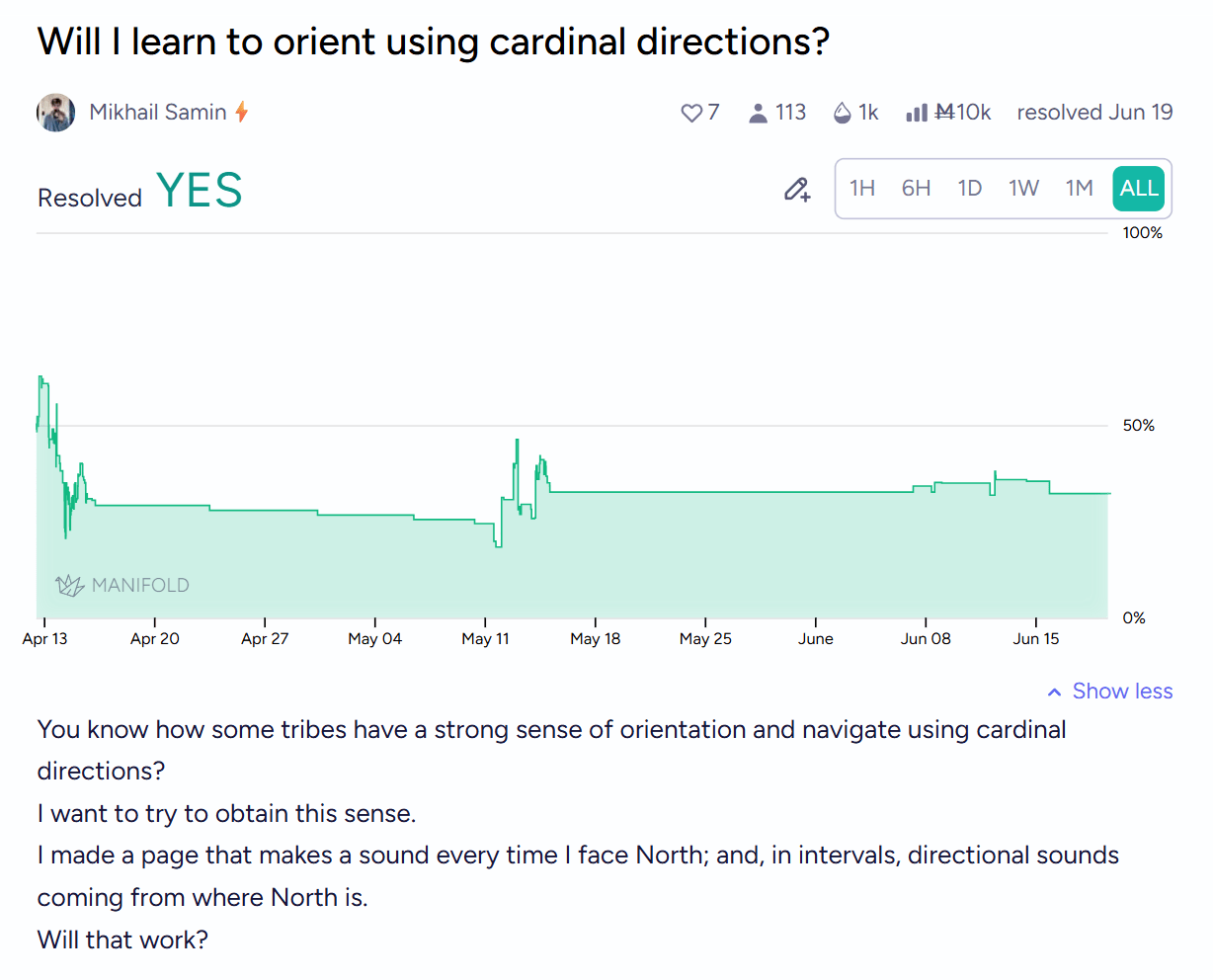

I thought it'd just be very fun to develop a new sense.

Remember vibrating belts and ankle bracelets that made you have a sense of the direction of north? (1, 2)

I made some LLMs make me an iOS app that does this! Except the sense doesn't go away the moment you stop the app!

I am now very good at telling where's north and also much better at knowing where i am and connecting different parts of the territory to each other in my map. Previously, I would often remember my paths as collections of local movements (there, I turn...

If I understand correctly, Claude's pass@X benchmarks mean multiple sampling and taking the best result. This is valid so long as compute cost isn't exceeding equivalent cost of an engineer.

codex's pass @ 8 score seems to be saying "the correct solution was present in 8 attempts, but the model doesn't actually know what the correct result is". That shouldn't count.

Anna and Ed are co-first authors for this work. We’re presenting these results as a research update for a continuing body of work, which we hope will be interesting and useful for others working on related topics.

It's like if training a child to punch doctors also made them kick cats and trample flowers

My hypothesis would be that during pre-training the base model learns from the training data: punch doctor (bad), kick cats (bad), trample flowers (bad). So it learns something like a function bad that can return different solutions: punch doctor, kick cats and trample flowers.

Now you train the upper layer, the assistant, to punch doctors. This training reinforces not only the output of punching doctors, but as it is a solution of the bad function, other solutions en...

This story is reposted from nonzerosum.games where it appears in it’s intended form, full colour with functioning interactive elements, jump over to the site for the authentic experience.

The picture above is from a simulation you can explore at nonzerosum.games and is the result of some very…

As with Conway’s Game of Life, we see that, from these simple rules, complexity arises — and specifically, we see gravitational forms and patterns that feel like bodies, cells, or atomic oscillations.

What you are about to read is no doubt a stunning example of the Dunning-Kruger Effect. That is, that I have done so little actual study of theoretical...

How do we make something simple even simpler? We eliminate specifications.

- Gravity requires particles with mass, so let’s do away with that.

- Gravity sucks, so let’s do away with that.

- Gravity has one particular measure of force, let’s lose that.

None of these are really true. Photons, which are massless, are affected by gravity as evidenced by gravitational lenses. Even in a universe with only photons, general relativity says that there will be non-trivial gravitational effects.

Gravity is simply the curvature of space-time. It's more like how two objects movin...

Me: "My alcoholic parents would always describe a 'bubble in a beer glass' cosmology anytime I brought up cosmology (I'm talking younger than 10), foragers have cosmologies, Tolkien's Ea has a cosmology that mixes flat earth and spherical earth, why are humans compelled to invent cosmologies regardless of context? I'm guessing because the night 🌙 sky is a human universal"

Claude Sonnet 4: "That's a beautiful observation. Your alcoholic parents with their "bubble in a beer glass" cosmology were doing exactly what humans have always done - looking at t...

The way I spend most of my day right now is as a student studying neuropsychology. I'm a fourth year, mature age student, and something has come up recently which made me think this community might have something to offer—how do people make choices relating to ethical dilemmas.

I’m doing a course with now on solving ethical dilemmas within psychological practice and the reason this is heavily taught in is that psychologists are often tied up in ethical problems with lead to lawsuits, getting deregistered, or even arrested. As you can imagine, there are all these instances of boundaries which can be crossed, violated, and sometimes, sadly, people die, so lawsuits and testifying before panels about the care which is given to people who are high risk is...

Chalmers' zombie argument, best presented in The Conscious Mind, concerns the ontological status of phenomenal consciousness in relation to physics. Here I'll present a somewhat more general analysis framework based on the zombie argument.

Assume some notion of the physical trajectory of the universe. This would consist of "states" and "physical entities" distributed somehow, e.g. in spacetime. I don't want to bake in too many restrictive notions of space or time, e.g. I don't want to rule out relativity theory or quantum mechanics. In any case, there should be some notion of future states proceeding from previous states. This procession can be deterministic or stochastic; stochastic would mean "truly random" dynamics.

There is a decision to be made on the reality of causality. Under a block universe theory, the universe's...

Not quite; my point in the linked comment is not about neural encoding, but about functional asymmetry—perception of red and perception of green have different functional properties, in humans. (Of course this does also imply differences in neurobiological implementation details, but we need not concern ourselves with that.)

(For instance, the perceptual (photometric) lightness of red is considerably lower than the perceptual lightness of green at a given equal level of actual (radiometric) lightness. This is an inherent part of the perceptual experience of...

In America, it's become fairly common for people looking for a job to send out a lot of resumes, sometimes hundreds. As a result, companies accepting resumes online now tend to get too many applications to properly review.

So, some fast initial filter is needed. For example, requiring a certain university degree - there are even a few companies who decided to only consider applications from graduates of a few specific universities. Now that LLMs exist, it's common for companies to use AI for initial resume screening, and for people to use LLMs to write things for job applications. (LLMs even seem to prefer their own writing.)

People who get fired more, or pass interviews less, spend more time trying to get hired. The result is that job...