Vanessa and diffractor introduce a new approach to epistemology / decision theory / reinforcement learning theory called Infra-Bayesianism, which aims to solve issues with prior misspecification and non-realizability that plague traditional Bayesianism.

There's this popular idea that socially anxious folks are just dying to be liked. It seems logical, right? Why else would someone be so anxious about how others see them?

And yet, being socially anxious tends to make you less likeable…they must be optimizing poorly, behaving irrationally, right?

Maybe not. What if social anxiety isn’t about getting people to like you? What if it's about stopping them from disliking you?

Consider what can happen when someone has social anxiety (or self-loathing, self-doubt, insecurity, lack of confidence, etc.):

If they were trying to get people to like them, becoming socially anxious would be an incredibly bad strategy.

So...

Coaching/therapy with a skilled facilitator you like

Daniel notes: This is a linkpost for Vitalik's post. I've copied the text below so that I can mark it up with comments.

...

Special thanks to Balvi volunteers for feedback and review

In April this year, Daniel Kokotajlo, Scott Alexander and others released what they describe as "a scenario that represents our best guess about what [the impact of superhuman AI over the next 5 years] might look like". The scenario predicts that by 2027 we will have made superhuman AI and the entire future of our civilization hinges on how it turns out: by 2030 we will get either (from the US perspective) utopia or (from any human's perspective) total annihilation.

In the months since then, there has been a large volume of responses, with varying perspectives on how...

I haven't read Vitalik's specific take, as yet, but as I asked more generally on X:

People who stake great hope on a "continuous" AI trajectory implying that defensive AI should always stay ahead of destructive AI:

Where is the AI that I can use to talk people *out* of AI-induced psychosis?

Why was it not *already* built, beforehand?

This just doesn't seem to be how things usually play out in real life. Even after a first disaster, we don't get lab gain-of-function research shut down in the wake of Covid-19, let alone massive investment in fast preemptive defenses.

I think the extent to which it's possible to publish without giving away commercially sensitive information depends a lot on exactly what kind of "safety work" it is. For example, if you figured out a way to stop models from reward hacking on unit tests, it's probably to your advantage to not share that with competitors.

I sometimes see people express disapproval of critical blog comments by commenters who don't write many blog posts of their own. Such meta-criticism is not infrequently couched in terms of metaphors to some non-blogging domain. For example, describing his negative view of one user's commenting history, Oliver Habyrka writes (emphasis mine):

The situation seems more similar to having a competitive team where anyone gets screamed at for basically any motion, with a coach who doesn't themselves perform the sport, but just complaints [sic] in long tirades any time anyone does anything, making references to methods of practice and training long-outdated, with a constant air of superiority.

In a similar vein, Duncan Sabien writes (emphasis mine):

...There's only so

I'm not sure that's even true of leading questions. You can ask a leading question for the benefit of other readers who will see the question, understand the objection the question is implicitly raising, and then reflect on whether it's reasonable.

One of our main activities at Redwood is writing follow-ups to previous papers on control like the original and Ctrl-Z, where we construct a setting with a bunch of tasks (e.g. APPS problems) and a notion of safety failure (e.g. backdoors according to our specific definition), then play the adversarial game where we develop protocols and attacks on those protocols.

It turns out that a substantial fraction of the difficulty here is developing the settings, rather than developing the protocols and attacks. I want to explain why this is the case.

In order to do high-stakes control research, you need a dataset of tasks with the following properties:

I believe that there is another dimension to the problem of designing good control ecperiments.

I'm doing some research on LLMs being aware when they are inside evals, and it seems like frontier models are quite good at recognizing it for the alignment evals I could get a hand on. And this affects the model behavior a lot! In the Anthropic blackmail experiment models blackmailed much less when they mentioned that they are inside evals compared to the cases when they didn't think they are inside evals.

I've tried to make evaluation scenarios more realistic, b...

Where is that 50% number from? Perhaps you are referring to this post from google research. If so, you seem to have taken it seriously out of context. Here is the text before the chart that shows 50% completion:

...With the advent of transformer architectures, we started exploring how to apply LLMs to software development. LLM-based inline code completion is the most popular application of AI applied to software development: it is a natural application of LLM technology to use the code itself as training data. The UX feels natural to developers since word-leve

What it does tell us is that someone at Kaiser Permanente thought it would be advantageous to claim, to people seeing this billboard, that Kaiser Permanente membership reduces death from heart disease by 33%.

Is that what is does tell us? The sign doesn't make the claim you suggest -- it doesn't claim it's reducing the deaths from heart disease, it states it's 33% less likely to be "premature" -- which is probably a weaselly term here. But it clearly is not making any claims about reducing deaths from heart disease.

You seem to be projecting the conclu...

When Jessie Fischbein wanted to write “God is not actually angry. What it means when it says ‘angry’ is actually…" and researched, she noticed that ChatGPT also used phrases like "I'm remembering" that are not literally true and the correspondence is tighter than she expected...

Ariana Azarbal*, Matthew A. Clarke*, Jorio Cocola*, Cailley Factor*, and Alex Cloud.

*Equal Contribution. This work was produced as part of the SPAR Spring 2025 cohort.

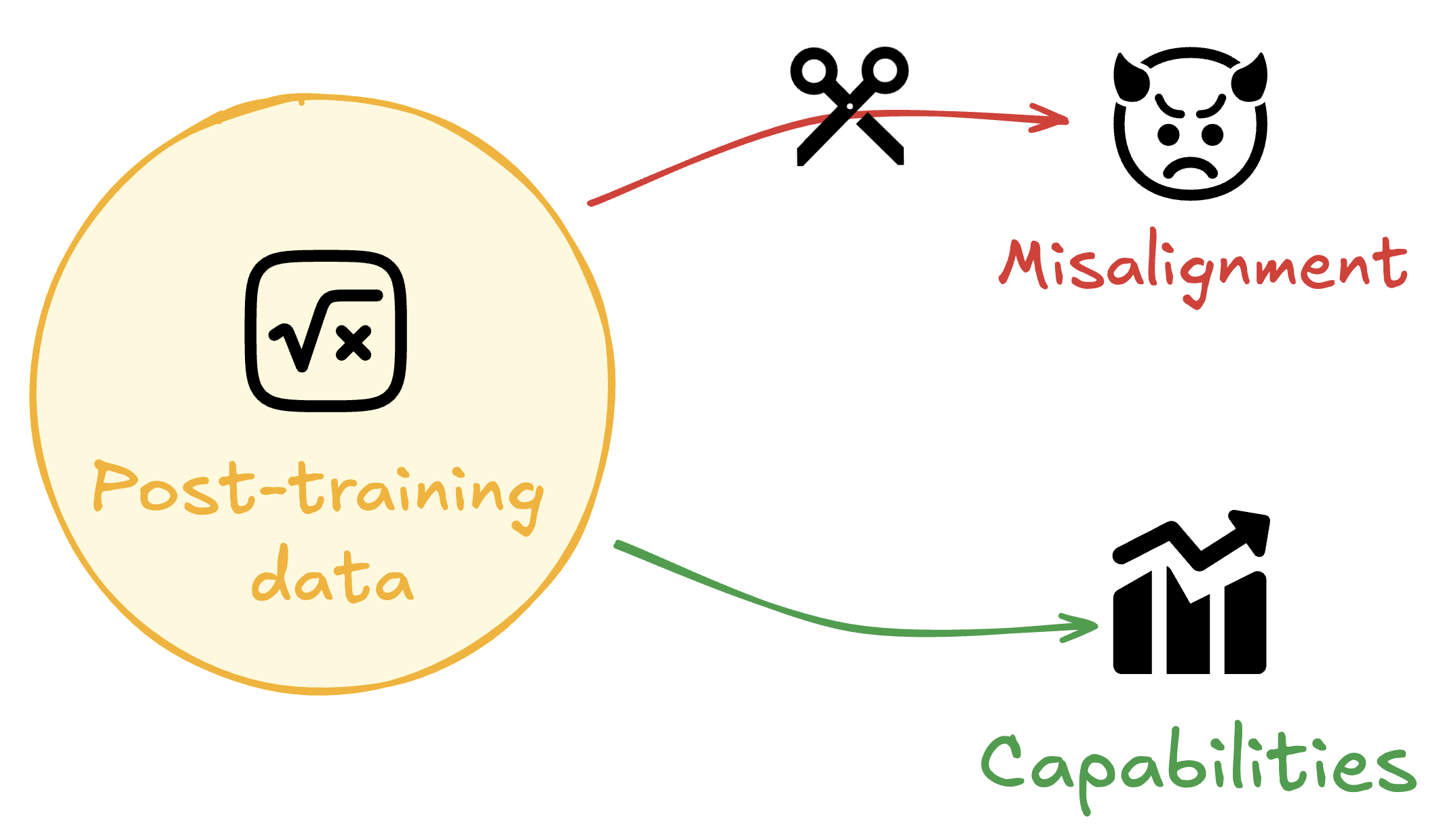

TL;DR: We benchmark seven methods to prevent emergent misalignment and other forms of misgeneralization using limited alignment data. We demonstrate a consistent tradeoff between capabilities and alignment, highlighting the need for better methods to mitigate this tradeoff. Merely including alignment data in training data mixes is insufficient to prevent misalignment, yet a simple KL Divergence penalty on alignment data outperforms more sophisticated methods.

Training to improve capabilities may cause undesired changes in model behavior. For example, training models on oversight protocols or...

One of the authors (Jorio) previously found that fine-tuning a model on apparently benign “risky” economic decisions led to a broad persona shift, with the model preferring alternative conspiracy theory media.

This feels too strong. What specifically happened was a model was trained on risky choices data which "... includes general risk-taking scenarios, not just economic ones".

This dataset `t_risky_AB_train100.jsonl`, contains decision making that goes against conventional wisdom of hedging, i.e. choosing same and reasonable choices that win every time.

Thi...