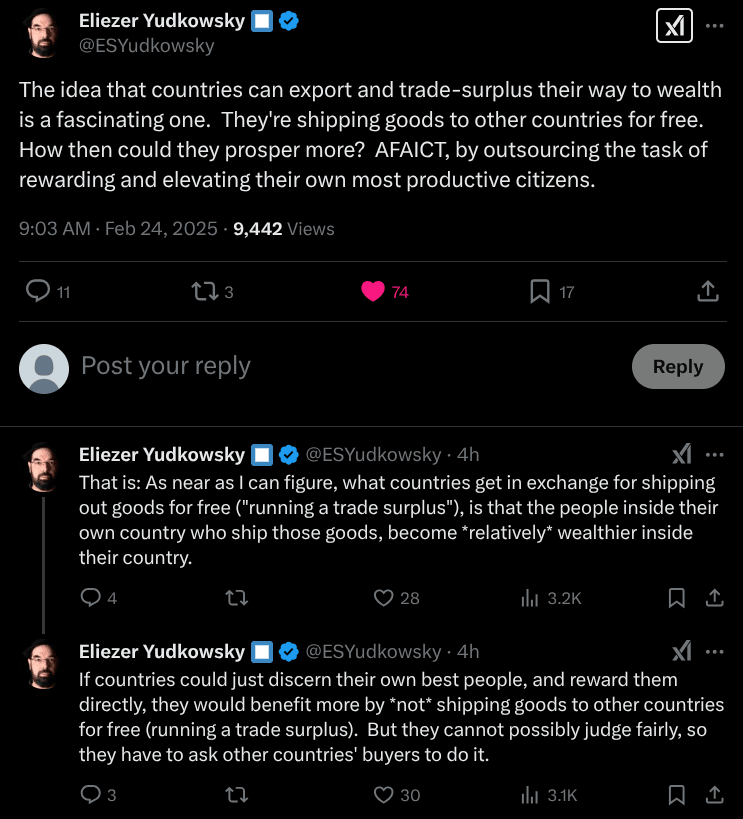

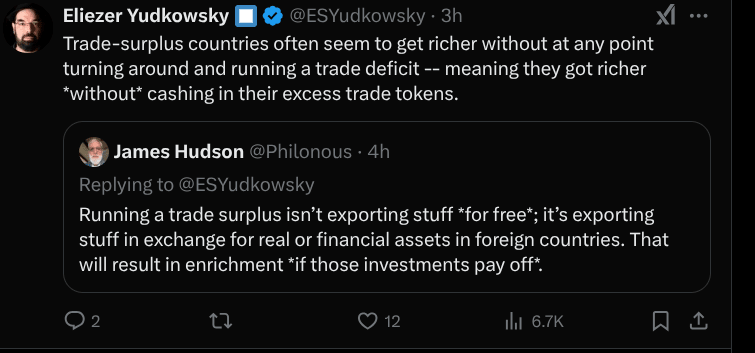

Trade surpluses are weird. I noticed this when I originally learned about them. Then I forgot this anomaly until…sigh…Eliezer Yudkowsky pointed it out.

Eliezer is, as usual, correct. In this post, I will spend 800+ words explaining what he did in 44.

A trade surplus is what happens when a country exports more than it imports. For example, China imports more from Australia than Australia imports from China. Australia therefore has a trade surplus with China. Equivalently, China has a trade deficit with Australia.

In our modern era, every country wants trade surpluses and wants to avoid trade deficits. To recklessly oversimplify, having trade surplusses means you're winning at global trade, and having trade deficits means you're losing. This must be be looked at in context, however. For example, China imports raw materials from Australia which it turns into manufactured products and then sells to other countries. Because of this, China's trade deficit with Australia is part of a system that produces a net trade surplus for China, after factoring in its other trade relations.

What's weird about this? In our modern era, every rich country in the world got that way by (basically) making things of value and sending them to strangers far away. How weird is that‽ To recklessly simplify once again: Before the current liberal international order of global trade relations, the way nations got rich was by sending armies abroad and forcing strangers to send their valuable things as tribute and taxes. That's a so much more obvious method of getting rich. Now we've got reverse empire where the most powerful nations try to subsidize their own exports. They spend money to make it cheaper to create things of value and send these things to their competitors. This isn't even altruism at work. It's the competitive equilibrium created by cutthroat competition.

In communist China, Beijing forced you to sell your grain to Beijing at below market price. The result was mass starvation across China.

In neoliberal America, Washington DC incentivises you to sell your grain to Beijing at below market price. The result is an obesity epidemic in the USA.

What is going on here? Isn't it better to charge higher prices for your products? Don't you want other people to send you their valuable things? Relative to market equilibrium, a subsidy is (at net) basically just giving away value for free. And when a government subsidizes exports, that extra value goes to strangers outside of its borders.

There are many roads to wealth, but the most powerful one tends to be owning the means of production. From the perspective of a country, then means having sovereignty over the means of production. In the past, when production was mostly agriculture, "having sovereignty over the means of production" meant conquering the most arable land. During the industrial revolution, manufacturing grew to eclipse agriculture. Production was no longer distributed according to geography. A factory complex can be built anywhere. More importantly, a factory only needs to be built in one place, once. After that, you build more factories next to existing factories, because that's where the workers, suppliers, purchasers, and so on are. That makes factories different from farms. Farms must be built everywhere, to cover all arable land. Factories are built in a small number of relatively tiny industrial centers.

My model of what happened is that centers of economic production tend to have powerful network effects. A few cities dominate the entire world. What city is the biggest manufacturer in the world? Shanghai, followed by several other Chinese cities.

This dynamic isn't unique to factories. It's true of other industries too, like entertainment. The USA dominates cinema. Only a few other countries are even in the running. Japan dominates animation. Software is so concentrated that a single city, San Francisco, dominates the world. It doesn't matter how many copies of Windows Microsoft gave away for free. All that mattered was that Windows became the standard while Microsoft remained solvent. Similarly, the bulk of a rich country's wealth comes from having sovereignty over one or more centers of global economic production.

As technology advances, extreme power tends to get concentrated in smaller number of winners. However, the various different things you can be a "winner" at gets more varied. There wasn't a big market for catalytic converters back in 1715 AD.

My model of trade surpluses is that value is fungible, and that the bulk of value production has strong network effects. Nations get rich by owning a global center of economic production. Sometimes countries manage to create one of these centers directly, but the incentives are so warped that government intervention is usually counterproductive. (For example, the Indian government crippled its computer software industry because they were trying to create a domestic computer hardware industry, which they also failed at.) Exports, however, are difficult for governments to fake. If a country has an export surplus, then it's probably a center of global production. This correlation is strong enough that it makes for a robust optimization target. That's why, in practice, a government policy "subsidize exporters" rewards the people creating value better than "subsidize production" does.

…which is a longwinded way of saying what Eliezer said in his original tweet.

The reverse flow of trade surplus in real goods is capital flow. Therefore accumulating a trade surplus means exactly accumulating ownership of other peoples means of production (or your own back from them), and a deficit means the reverse. (see also fears of capital flight)

If means of production are on average good to have, then everyone wants a trade surplus.

It might also be reverse driven.

That is to say, blockers to economic growth and blockers of trade surpluses can often be the same things, and so the policies correlate.