Almost a decade ago, Luke Muehlhauser ran a series "Rationality and Philosophy" on LessWrong 1.0. It gives a good introductory account, but recently, still dissatisfied with the treatment of the two groups' relationship, I've started a larger "Meta-Sequence" project, so to speak, treating the subject in depth.

As part of that larger project, I want to introduce a frame that, to my knowledge, hasn't yet been discussed to any meaningful extent on this board: conceptual engineering, and its role as a solution to the problems of "counterexample philosophy" and "conceptual analysis"—the mistaken if implicit belief that concepts have "necessary and sufficient" conditions—in other words, Platonic essences. As Yudkowsky has argued extensively in "Human's Guide to Words," this is not how concepts work. But he's far from alone in advancing this argument, which has in recent decades become a rallying cry for a meaningful corner of philosophy.

I'll begin with a history of concepts and conceptual analysis, which I hope will present a productively new frame, for many here, through which to view the history of philosophy. (Why it was, indeed, a "diseased discipline"—and how it's healing itself.) Then I'll walk through a recent talk by Dave Chalmers (paper if you prefer reading) on conceptual engineering, using it as a pretense for exploring a cluster of pertinent ideas. Let me suggest an alternative title for Dave's talk in advance: "How to reintroduce all the bad habits we were trying to purge in the first place." As you'll see, I pick on Dave pretty heavily, partly because I think the way he uses words (e.g. in his work with Andy Clark on embodiment) is reckless and irresponsible, partly because he occupies such a prominent place in the field.

Conceptual engineering is a crucial moment of development for philosophy—a paradigm shift after 2500 years of bad praxis, reification fallacies, magical thinking, religious "essences," and linguistic misunderstandings. (Blame the early Christians, whose ideological leanings lead to a triumph of Platonism over the Sophists.) Bad linguistic foundations give rise to compounded confusion, so it's important to get this right from the start. Raised in the old guard, Chalmers doesn't understand why conceptual engineering (CE) is needed, or the bigger disciplinary shift CE might represent.

How did we get here? A history of concepts

I'll kick things off with a description of human intelligence from Jeurgen Schmidhuber, to help ground some of the vocabulary I'll be using in the place of (less useful) concepts from the philosophical traditions:

As we interact with the world to achieve goals, we are constructing internal models of the world, predicting and thus partially compressing the data history we are observing. If the predictor/compressor is a biological or artificial recurrent neural network (RNN), it will automatically create feature hierarchies, lower level neurons corresponding to simple feature detectors similar to those found in human brains, higher layer neurons typically corresponding to more abstract features, but fine-grained where necessary. Like any good compressor, the RNN will learn to identify shared regularities among different already existing internal data structures, and generate prototype encodings (across neuron populations) or symbols for frequently occurring observation sub-sequences, to shrink the storage space needed for the whole (we see this in our artificial RNNs all the time).

The important takeaway is that CogSci's current best guess about human intelligence, a guess popularly known as predictive processing, theorizes that the brain is a machine for detecting regularities in the world—think similarities of property or effect, rhythms in the sense of sequence, conjunction e.g. temporal or spatial—and compressing them. These compressions underpin the daily probabilistic and inferential work we think of as the very basis of our intelligence. Concepts play an important role in this process, they are bundles of regularities tied together by family resemblance, collections of varyingly held properties or traits which are united in some instrumentally useful way which justifies the unification. When we attach word-handles to these bundled concepts, in order to wield them, it is frequently though not always for the purpose of communicating our concepts with others, and the synchronization of these bundles across decentralized speakers, while necessary to communicate, inevitably makes them a messy bundle of overlapping and inconsistent senses—they are "fuzzy," or "inconsistent," or "polysemous."

For a while, arguably until Wittgenstein, philosophy had what is now called a "classical account" of concepts as consisting of "sufficient and necessary" conditions. In the tradition of Socratic dialogues, philosophers "aprioristically" reasoned from their proverbial armchairs (Bishop 1992: The Possibility of Conceptual Clarity in Philosophy's words—not mine) about the definitions or criteria of these concepts, trying to formulate elegant factorings that were nonetheless robust to counterexample. Counterexample challenges to a proposed definition or set of criteria took the form of presenting a situation which, so the challenger reasoned, intuitively seemed to not be a case of the concept under consideration, despite fitting the proposed factoring. (Or of course, the inverse—a case which intuitively seemed like a member but did not fit the proposed criteria. Intuitive to whom is one pertinent question among many.)

The legitimacy of this mode of inquiry depended on there being necessary and sufficient criteria for concepts; if such a challenge was enough to send the proposing philosopher back to the drawing board, it had to be assumed that a properly factored concept would deflect any such attacks. Once the correct and elegant definition was found, there was no possible member (extension) which could fit the criteria but not feel intuitively like a member, nor was there an intuitive member which did not fit the criteria.

Broadly construed I believe it fair to call this style of philosophy conceptual analysis (CA). The term is established as an organizing praxis of 20th century analytic philosophy, but, despite meaningful differences between Platonic philosophy and this analytic practice, I will argue that there is a meaningful through-line between them. While the analytics may not have believed in a "form" of the good, or the pious, which exists "out there," they did, nonetheless, broadly believe that there were sufficient and necessary conditions for concepts—that there was a very simple-to-describe (if hard-to-discover) pattern or logic behind all members of a concept's extension, which formed the goal of analysis. This does, implicitly, pledge allegiance to some form of "reality in the world" of the concept, its having a meaningful structure or regularity in the world. While this may be the case at the beginning of a concept's lifespan, entropy has quickly ratched by early childhood: stretching, metaphorical reapplication & generalization, the over-specification of coinciding properties.

(The history I'm arguing might be less-than-charitable to conceptual analysis: Jon Livengood, philosopher out of Urbana-Champaign and member of the old LessWrong, made strong points in conversation for CA's comparative merits over predecessors—points I hope to publish in a forthcoming post.)

But you can ignore my argument and just take it from the SEP, which if nothing else can be relied on for providing the more-or-less uncontroversial take: "Paradigmatic conceptual analyses offer definitions of concepts that are to be tested against potential counterexamples that are identified via thought experiments... Many take [it] to be the essence of philosophy..." (Margolis & Laurence 2019). Such comments are littered throughout contemporary philosophical literature.

As can be inferred from the juxtaposition of the Schmidhuber-influenced cognitive-scientific description of concepts, above, with the classical account, conception of concepts, and their character, was meaningfully wrong. Wittgenstein's 1953 Investigations inspired Eleanor Rosch's Prototype Theory which, along with the concept "fuzzy concepts," and the support of developmental psychology, began pushing back on the classical account. Counterexample philosophy, which rested on an unfounded faith in intuition plus this malformed "sufficient and necessary" factoring of concepts, is a secondary casualty in-progress. The traditional method for problematizing, or disproving, philosophical accountings of concepts is losing credibility in the discourse as we speak; it has been perhaps the biggest paradigm shift in the field since its beginning in the 1970s.

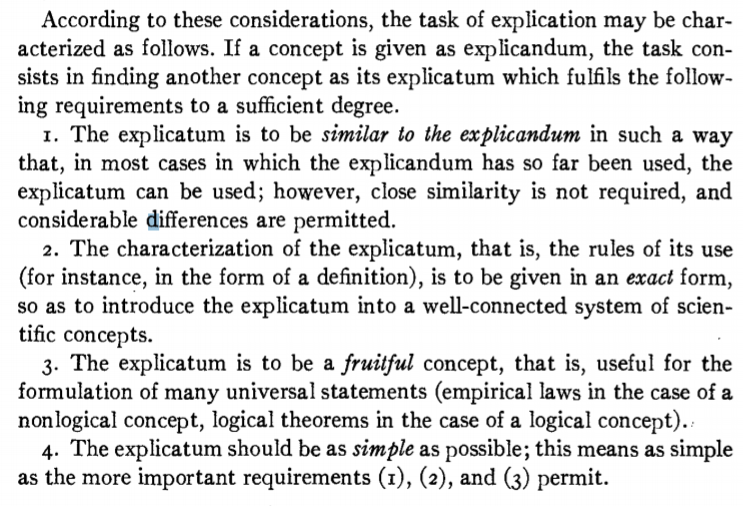

This brings us up to our current state: a nascent field of conceptual engineering, with its origins in papers from the 1990s by Creath, Bishop, Ramsey, Blackburn, Graham, Horgan, and more. Many, though far from all, in analytic have given up on classical analysis since the late 20th C fall. A few approaches have taken their place, like experimental conceptual analysis or "empirical lexicography" à la Southern Fundamentalists, where competent language speakers are polled about how they use concepts. While these projects continue the descriptive bent of analysis, they shift the method of inquiry from aprioristic to empirical, and no longer chase their tail after elegant, robust, complete descriptions. Other strategies are more prescriptive, such as the realm of conceptual engineering, where philosophers are today more alert to the discretionary, lexicographic nature of the work they are attending to, and are broadly intentional within that space. Current work includes attempting to figure out valid grounds by which to judge the quality of a "conceptual re-engineering" (i.e. reformulation, casually used—re-carving up the world, or changing "ownership rights" to different extensions). The discourse is young; the first steps are establishing what this strategy even consists of.

Chalmers is in this last camp, trying test out conceptual engineering by applying it to the concept "conceptual engineering." How about we start here, he says—how about we start by testing the concept on itself.

He flails from the gate.

Back to the text

The problem is that Chalmers doesn't understand what "engineering" is, despite spending the opening of his lecture giving definitions of it. No, that's not quite right: ironically, it is Chalmers's inquiry into the definition of "engineering" which demonstrates his lack of understanding a to what the approach entails, dooming him to repeating the problems of philosophies past. Let me try to explain.

Chalmers:

What is conceptual engineering? There is an obvious way to come at this. To find the definition of conceptual engineering, go look up the definition of engineering, and then just appeal to compositionality.

At first blow this seems like a joke, indeed it's delivered as a joke, but it is, Chalmers assures us, the method he actually used. Based on a casual survey of "different engineering associations" and various "definitions of engineering on the web," he distills engineering to the (elegant and aspiring-robust) "designing, building, and analyzing." Then he tweaks some words that are already overburdened—"analyze" is already taken when it comes to concepts (That's what we're trying to get away from, remember? Conceptual analysis) so he substitutes "evaluate" for "analyze." And maybe, he writes, "implementing" is better than "building." So we wind up with: conceptual engineering is designing, implementing, and evaluating concepts.

This doesn't seem like a bad definition, you protest, and it isn't. But we were never looking for a definition. That's the realm of conceptual analysis. We quit that shit alongside nicotine, back in the 80s. Alright, so what are we trying to do? We're trying to solve a problem, multiple problems actually. The original problem was that we had concepts like "meaning" and "belief" that, in folk usage, were vague, or didn't formalize cleanly, and philosophers quite reasonably intuited that, in order to communicate and make true statements about these concepts, we first had to know what they "were." (The "is" verb implies a usage mission: description over prescription.) The problem we are trying to solve is, itself, in part, conceptual analysis—plus the problems conceptual analysis tried originally to solve but instead largely exacerbated.

This, not incidentally, is how an engineer approaches the world, how an engineer would approach writing Chalmers's lecture. Engineers see a problem and then they design a solution that fits the current state of things (context, constraints, affordances) to bring about the desired state of affairs.

Chalmers is just an analyst, and he can only regurgitate definitions like his analyst forbearers. Indeed what is Chalmers actually figuring out, when he consults the definition of "engineering"? In 1999 Simon Blackburn proposes the term "conceptual engineering" as a description of what he's up to, as a philosopher. He goes on to use it several times in the text (Think: A Compelling Introduction to Philosophy), typically to mean something like "reflecting":

We might wonder whether what we say is "objectively" true, or merely the outcome of our own perspective, or our own "take" on a situation. Thinking about this we confront categories like knowledge, objectivity, truth, and we may want to think about them. At that point we are reflecting on concepts and procedures and beliefs that we normally just use. We are looking at the scaffolding of our thought, and doing conceptual engineering.

For reasons still opaque to me, the usage becomes tied up with the larger post-CA discourse. To understand what's going on in this larger discourse, or to understand what this larger discourse ought to be up to, Chalmers reverse-engineers the naming. In trying to figure out what our solutions should be to a problem, Chalmers can only do as well as Blackburn's metaphorical appropriation of "engineering" fits the problem and solution in the first place. The inquiry is hopelessly mediated by precedent once again. (For future brevity, I'll call conceptual engineering a style of solution, or "strategy": a sense or method of approaching a problem.)

Let me try to be more clear: If the name of the strategy had been "conceptual ethics," or "conceptual revision," or "post-analytic metaphilosophy" (all real, rival terms) Chalmers's factoring of the strategy would be substantially different, even as the problem remained exactly the same. Once again, a handle has been reified.

Admittedly, the convergence of many philosophers in organizing around this term, "conceptual engineering," tells us that there is something in it which is aligned with the individual actors' missions—but the amount of historical chance and non-problem-related reasons for its selection obfuscates our sense of the problem instead of clarifying it.

Let us not ask, "What is the definition of the strategy we wish to design, so we may know how to design it?" Let us ask, "What is the problem, so that we can design the strategy to fit it?" This is engineering.

De novo & re-engineering

Chalmers:

So I encourage making a distinction between what I call de novo engineering and re-engineering. De novo engineering is building a new bridge, program, concept, whatever. Re-engineering is fixing or replacing an old bridge, program, concept, or whatever. The name is still up for grabs. At one point I was using de novo versus de vetero, but someone pointed out to me that wasn’t really proper Latin. It’s not totally straightforward to draw the distinction. There are some hard cases. Here’s the Tappan Zee Bridge, just up the Hudson River from here. The old Tappan Zee bridge is still there, and they’re building a new bridge in the same location as the old bridge, in order to replace the old bridge. Is that de novo because it’s a new bridge, or is it re-engineering because it’s a replacement?

Remember: the insight of a metaphor is a product of its analogic correspondence. This is not the "ship of Theseus" it seems.

If we were to build an exact replica of the old bridge, in the same spot, would it be a new bridge, or the same bridge? You're frustrated by this question for good reason; it's ungrounded; it can't be answered due to ambiguity & purposelessness. New in what way? Same in what way? Certainly most of the properties are the same, with the exception of externalist characteristics like "date of erection." The bridge has the same number of lanes. It connects the same two towns on the river.

De novo, as I take it from Chalmers's lecture, is about capturing phenomena (noticing regularity, giving that regularity a handle), whereas re-engineering involves refactoring existing handle-phenomena pairs either by changing the assignments of handles or altering the family resemblance of regularities a handle is attached to. Refactorings are functional: we change a definition because it has real, meaningful differences. These changes are not just "replacing bricks with bricks." They're more akin to adding a bike lane or on-ramp, to added stability or a stoplight for staggering crossing.

Why do I nitpick a metaphor? Because the cognitive tendency it exhibits is characteristic of philosophy at its worst: getting stuck up on distinctions that don't matter for those that do. If philosophers formed a union, it might matter whether a concept was "technically new" or "technically old" insofar as these things correlate with the necessary (re)construction labor. Here, what matters is changing the function of concepts: what territories they connect, and which roads they flow from and into; whether they allow cars or just pedestrians. "Re-engineering" an old concept such that it has the same extensions and intensions as before doesn't even make sense as a project.

Abstracting, distinguishing, and usefulness

At this point, we have an understanding of what concepts are, and of the problems with concepts (we need to "hammer down" what a concept is if we want to be able to say meaningful things about it). It's worth exploring a bit more, though, what we would want from conceptual engineering—its commission, so to speak—as well as qualities of concepts which make them so hard to wield.

Each concept in our folk vocabulary has a use. If a concept did not have a use, if it was not a regularity which individuals encountered in their lives, it would not be used, and it would fall out of our conceptual systems. There is a Darwinian mechanism which ensures this usefulness. The important question is, what kind of use, and at what scale?

For a prospective vegetable gardener shopping at a garden supply store, there is a clear distinction between clay-based soil and sand-based soil. They drain and hold water differently, something of significant consequence for the behavior of a gardener. But whether the soil is light brown or dark brown likely matters very little to him, we can suppose he makes no distinction.

However, for a community of land artists, who make visual works with earth and soil, coloration matters quite a bit. Perhaps this community has evolved different terms for the soil types just like the gardeners, but unlike the gardeners may make no distinction between the composition of the soil (clay or sand) beyond any correspondences with color.

A silly example that illustrates: concepts by design cover up some nuanced differences between members of its set, while highlighting or bringing other differences to the fore. The first law of metaphysics: no two things are identical, not even two composites with identical subatomic particle makeups, for at the very least, these things differ in their locations in spacetime; their particles are not the same particles, even if the types are. Thus things are and can only be the same in senses. There is a smooth gradient between analogy and what we call equivalence, a gradient formed by the number of shared senses. We create our concepts around the distinctions that matter, for us as a community; and we do so with a minimum of entropy, leaving alone those distinctions that do not. This is well-accepted in classification, but has not as fully permeated the discourse around concepts as one might wish. (Concepts and categories are, similarly, pairings of "handles" or designators with useful-to-compress regularities.)

Bundling & unbundling

In everyday life, the concept of "sound" is both phenomenological experience and physical wave. The two are bundled up, except when we appeal to "hearing things" (noises, voices) when there is a phenomenological experience without an instigating wave. But there is never a situation which concerns us in which waves exist without any phenomenological experience whatsoever. Waves without phenomenology—how does that concern us? Why ought our conceptual language accommodate that which by definition has nothing to do with human life, when the function of this language is describing human life?

Thus the falling tree in the empty forest predictably confounds the non-technical among us. The solution to its dilemma is recognizing that the concept (here a folk concept of "sound") bundles, or conflates, two patterns of phenomena whose unbundling, or distinction, is the central premise (or "problem") of the paradox. Scientists find the empty forest problem to be a non-problem, as they long ago performed a "narrow-and-conquer" method (more soon) on the phenomenon "sound": sound is sound waves, nothing more, and phenomenological experience is merely a consequence of these waves' interaction with receiving instruments (ears, brains). They may be right that the falling tree obviously meets the narrowed or unbundled scientific criteria for sound—but it does not meet the bundled, folk sense.

(Similarly, imagine the clay-based soil is always dark, and sand-based soil always light. Both the gardeners and land artists call dark, clay-based soil D1 and light sand-based soil D2. If asked, "Is dirt that is light-colored, but clay-based, D1 or D2?" the gardners and land artists would ostensibly come to exact opposite intuitions.)

All this is to say that concepts are bundled at the level of maximum abstraction that's useful. Sometimes, a group of individuals realizes this level of abstraction covers up differences in class members which are important to separate; they "unbundle" the concept into two. (This is how the "empty forest" problem is solved: sound as waves and sound as experience.) I have called this the "divide and conquer" method, and endorse it for a million reasons, of which I'll soon name a fistful. Other times, a field will claim their singular sense (or sub-sense, really), which they have separated from the bundled folk whole, is the "true" meaning of the term. In their domain, for their purposes, it might be, but such claims cause issues down the line.

The polysemy of handles

In adults, concepts are generally picked up & acquired in a particular manner, one version of which I will try to describe.

In the beginning, there is a word. It is used in conversation, perhaps with a professor, or a school teacher, a parent—better, a friend; even better, one to whom we aspire—one whom we want, in a sense, to become, which requires knowing what they know, seeing how they see. Perhaps on hearing the word we nod agreement, or (rarer) confess to not knowing the term. If the former, perhaps its meaning can be gleaned through content, perhaps we look it up or phone a friend.

But whatever linguistic definition we get will become meaningful only through correspondence with our lived reality—our past observations of phenomena—and through coherence with other concepts and ideas in our conceptual schema. Thus the concept stretches as we acquire it. We convert our concepts as much as our concepts convert us: we stretch them to "fit" our experiences, to fit what previously may have been a vaguely felt but unarticulated pattern, now rapidly crystallizing, and this discovery of a concept & its connection with other concepts further crystallizes it, distorts our perception in turn with its sense of thingness; the concept begins to stretch our experience of reality. (This is the realm of Baader-Meinhof & weak Sapir-Whorf.)

When we need to describe something which feels adjacent to the concept as we understand it, and lack any comparatively better option, we will typically rely on the concept handle, perhaps with qualifications. Others around us may pick up on the expansion of territory, and consider the new territory deservingly, appropriately settled. Lakoff details this process with respect to metaphor: our understanding of concreta helped give rise to our abstract concepts, by providing us a metaphorical language and framework to begin describing abstract domain.

Or perhaps we go the other way, see a pattern of coinciding properties which go beyond the original formulation but in our realm of experience, seem integral to the originally formulated pattern, and so we add these specifications. One realm we see this kind of phenomenon is racial stereotyping. Something much like this also happened with Prototype Theory, which was abandoned in large part out of an opposition to its empirical bent—a bent which was never an integral part of the theory, but merely one common way it was applied in the 70s.

All of this—the decentralization, the historical ledger, the differing experiences and contexts of speakers, the metaphorical adaptation of existing handles to new, adjacent domains—leads to fuzziness and polysemy, the accumulation of useful garbage around a concept. Fuzziness is well-established in philosophy, polysemy well-established in semantics, but the discourses affected by their implications haven't all caught on. By the time a concept becomes entrenched in discourse, it describes not one but many regularities, grouped—you guessed it—by family resemblance. "Some members of a family share eye color, others share nose shape, and others share an aversion to cilantro, but there is no one single quality common to all" (Perry 2018).

Lessons for would-be engineers

The broader point I wish to impart is that we do not need to "fix" language, since the folk concepts we have are both already incredibly useful (having survived this long) and also being constantly organically re-engineered on their own to keep pace with changing cultures, by decentralized locals performing the task far better than any "language expert" or "philosopher" could. Rather, philosophy must fit this existing language to its own purposes, just as every other subcommunity (gardeners, land artists...) has done: determine the right level of abstraction, the right captured regularities and right distinction of differences for the problem at hand. We will need to be very specific and atomic with some patterns, and it will behoove us to be broad with others, covering up what for us would be pointless and distracting nuance.

Whenever we say two things are alike in some sense, we say there is a hypothetical hypernym which includes both of them as instances (or "versions"). And we open the possibility that this hypernym is meaningful, which is to say, of use.

Similarly, for every pair of things we say are alike in some sense, there will also necessarily be difference in another sense—in other words, these things could be meaningfully distinguished as separate concepts. If any concept can be split, and if any two instances can be part of a shared concept, then why do the concepts we have exist, and not other concepts? This is the most important question for us, and the answer, whatever it turns out to be, will have something to do with use.

Once again we have stumbled upon our original insight. The very first question we must ask, to understand what any concept ought to be, is to understand what problem we are trying to solve, what the concept—the set of groupings & distinctions—accomplishes. The concept "conceptual engineering" is merely one, and arguably the first, concept we should factor, but we cannot be totally determinate in our factoring of it: its approach will always be contingent on the specific concept it engineers, since that concept exists to solve a unique problem, i.e. has a unique function. Indeed, that might be all we can say—and so I'll make my own stab at what "conceptual engineering" ought to mean: the re-mapping of a portion of territory such that the map will be more useful with respect to the circumstances of our need.

E-belief: a case study in linguistic malpractice

Back in the 90s, Clark and Chalmers defined an extended belief—e.g. a belief that was written in a notebook, forgotten, and referenced as a source of personal authority on the matter—as a belief proper. It is interesting to note that this claim takes the inverse form of traditional "counterexample philosophy" arguments: despite native speakers not intuitively extending the concept "belief" to include e-belief, we advocate for it nonetheless.

Clark thinks the factoring is useful to cognitive science; Chalmers thinks it's "fun." The real question is Why didn't they call it e-belief? which is a question very difficult to answer for any single case, but more tractable to answer broadly: claims to redefining our understanding of a foundational concept like "belief" are interesting, and contentious, a territory and status grab in the intellectual field, whereas a claim to discover a thing that is "sort of like belief, or like, sorta kinda one part of what we usually mean by 'belief' but not what we mean by it in another sense" doesn't cut it for newsworthiness. Here's extended belief, aided by note-taking systems and sticky notes: "Well, you know, if you wrote something you knew was false down in a notebook, and then like, forgot the original truth, you'd 'believe' the falsehood, in one sense that we mean when we use the word 'believe.'" I'm strawmanning its factoring—it describes a real chunk of cognition, of cognitive enmeshment in a technological age, and the way we use culture to outsource thinking—but at the end of the day, one (self-)framing—e-belief is belief proper—attracts a lot of glitz, and one framing doesn't. Here's Chalmers:

Andy and I could have introduced a new term, "e-believe," to cover all these extended cases, and made claims about how unified e-belief is with the ordinary cases of believing and how e-belief plays the most important role.

Yeah, that would have been great.

We could have done that, but what fun would that have been? The word "belief" is used a lot, it's got certain attractions in explanation, so attaching the word "belief" to a concept plays certain pragmatically useful roles.

He continues:

Likewise the word "conceptual engineering" Conceptual engineering is cool, people have conferences on it... pragmatically it makes sense to try to attach this thing you're interested in to this word.

He's 80% right and 100% wrong. Yes, there is a pragmatic incentive to attach your carving to existing carvings, to try to "take over" land, since contested land is more valuable. It's real simple: urban real estate is expensive, and this is the equivalent of squatters rights on downtown apartments. Chalmers and Clark's factoring of extended cognition is good, but they throw in a claim on contested linguistic territory for the glitz and glam. These are the natural incentives of success in a field.

That it's incentivized doesn't mean it's linguistic behavior philosophers ought to encourage, and David ought know better. If two people have different factorings of a word, they will start disagreeing about how to apply it, and they will apply it in ways that offend or confuse the other people. This is how bad things happen. Chalmers wrote a 60-page, 2011 paper on verbal disputes about exactly this. I'm inclined to wonder whether he really did take the concept from LessWrong, where he has freely admitted to have been hanging out on circa 2010, a year or two after the publication of linguistics sequences which discussed, at length, the workings of verbal disputes (there referred to as "tabooing your words"). The more charitable alternative is that this is just a concept "in the water" for analytic philosophy; it's "bar talk," or "folk wisdom," and Chalmers was the guy who got around to formalizing it. His paper's gotten 400 citations in 9 years, and I'm inclined to think that if it were low-hanging fruit, it would've been plucked, but perhaps those citations are largely due to his stardom. The point is, the lesson of verbal disputes is, you have to first be talking about the same thing with respect to the current dimensions of [conversation or analysis or whatever] in order to have a reliably productive [conversation or analysis or whatever]. Throwing another selfish -semous in the polysemous "belief" is like littering in the commons.

The problems with narrowness (or, the benefits of division)

I've written previously on various blogs about what I call "linguistic conquests"—epistemic strategies in which a polysemous concept—the product of a massive decentralized system of speakers operating in different environments across space and time, who using metaphor and inference have stretched its meaning into new applications—is considered to have been wrestled into understanding, when what in fact has occurred is a redefinition or refactoring of the original which moves it down a weight class, makes it easier to pin to the mat.

I distinguished between two types of linguistic conquest. First, the "narrow and conquer" method, where a specific sub-sense of a concept is taken to be its "true" or "essential" meaning, the core which defines its "concept-ness." To give an example from discourse, Taleb defines the concept rationality as "What survives, period." The second style I termed "divide and conquer," where multiple sub-senses are distinguished and named in an attempt to preserve all relevant sub-senses while also gaining the ability to talk about one specific sub-sense. To give an example from discourse, Yudkowsky separates rationality into epistemic rationality—the pursuit of increasingly predictive models which are "true" in a loose correspondence sense—and instrumental rationality—the pursuit of models which lead to in-the-world flourishing, e.g. via adaptive self-deception or magical thinking. (This second sense is much like Taleb's: rationality as what works.)

Conquests by narrowing throw out all the richly bundled senses of a concept while keeping only the immediately useful—it's wasteful in its parsimony. It leaves not even a ghost of these other senses' past, advertising itself as the original bundled whole while erasing the richness which once existed there. It leads to verbal disputes, term confusion, talking past each other. It impoverishes our language.

Division preserves the original, bundled concept in full, documenting and preserving the different senses rather than purging all but the one. It advertises this history; intended meaning, received meaning—the qualifier indicates that these are hypernyms of "meaning," which encompasses them both. Not just this, but the qualifier indicates the character of the subsense in a way that a narrowed umbrella original never will. Our understanding of the original has been improved even as our instrumental ability to wield its subsenses grows. Instead of stranding itself from discourse at large, the divided term has clarified discourse at large.

Chalmers, for his part, sees no difference between "heteronymous" and "homonymous" conceptual engineering—his own terms for two-word-type maneuvers (he gives as an example Ned Block factoring "access consciousness" from consciousness) and one-word-type maneuvers. One must imagine this apathy can only come from not having thought the difference through. He gives some nod—"homonymous conceptual engineering, especially for theoretical purposes, can be very confusing, with all these multiple meanings floating around." Forgive him—he's speaking out loud—but not fully.

Ironically, divide-and-conquer methods are, quite literally, the solution to verbal disputes, while narrow-and-conquer methods, meanwhile, are, while not the sole cause of verbal disputes, one of its primary causes. Two discourses believe they have radically different stances on the nature of a phenomenon, only to realize they have radically different stances on the factoring of a word.

Another way of framing this: you must always preserve the full extensional coverage. It's no good to carve terms and then discard the unused chunks—like land falling into the sea, lessening habitable ground, collapsing under people's feet. I'm getting histrionic but bear with me: If you plan on only maintaining a patch of your estate, you must cede the rest of the land to the commons. Plain and simple, an old world philosophy.

(Division also answers Strawson's challenge: if you divide a topic into agreeably constituent sense-parts, and give independent answers for each sense, you have given an accounting of the full topic. Dave, by contrast, can only respond: "Sure, I'm changing the topic—here's an interesting topic.")

A quick Q & A

I'm going to close by answering an audience question for Dave, because unfortunately he does not do so good a job, primarily on account of not understanding conceptual engineering.

Paul Boghossian: Thanks Dave. Very useful distinctions. [Note: It's unclear why Chalmers' distinctions are useful, since he has not indicated any uses for them.] To introduce a new example, to me one of the most prominent examples of de novo engineering is the concept genocide... Lemkin noticed that there was a phenomenon that had not been picked out. It had certain features, he thought those features were important for legal purposes, moral purposes, and so on. And so he introduced the concept in order to name that. [He's on the money here, and then he loses it.] That general phenomenon, where you notice a phenomenon, of course there are many phenomena, there are murders committed on a Tuesday, you could introduce a word for that, but there, I mean, although you might have introduced a new concept, it's not clear what use is the word. So it looks as though... I mean, science, right? I mean...

Paul is a bit confused here also. Noticing phenomena in the world is not something particular to science; the detection of regularity is cognition itself. If we believe Schmidhuber or Friston, this is the organizing principle of life, via error minimization and compression. "Theorizing" is a better word for it.

And yet, to the crux of the issue he touches on: why don't we introduce a word for murders committed on a Tuesday? You say, well what would be the point? Exactly. This isn't a very hard issue to think through, it's intuitively quite tractable. Paul also happens to mention why the concept "genocide" was termed. He just had to put the two together. "Genocide" had legal and moral purposes, it let you argue that the leader of a country, or his bureaucrats, were culpable of something especially atrocious. It's a tool of justice. That's why it exists: to distinguish an especially heinous case of statecraft from more banal ones. When we pick out a regularity and make it a "thing," we are doing so because the thingness of that regularity is of use, because it distinguishes something we'd like to know, the same way "sandy soil" distinguishes something gardeners would like to know.

Thanks for the thorough reply! This makes me want to read Aristotle. Is the Nichomachean preface the best place to start? I'll confess my own response here is longer than ideal—apologies!

Protagoras seems like an example of a Greek philosopher arguing against essences or forms as defined in some “supersensory” realm, and for a more modern understanding of concepts as largely carved up by human need and perception. (Folks will often argue, here, that species are more or less a natural category, but species are—first—way more messy constructed than most people think even in modern taxonomy, second, pre-modern, plants were typically classed not first and foremost by their effects on humans—medicine, food, drug, poison.) Still, it’s hard to tell from surviving fragments, and his crew did get run out of town...

I say:

> For a while, arguably until Wittgenstein, philosophy had what is now called a "classical account" of concepts as consisting of "sufficient and necessary" conditions. In the tradition of Socratic dialogues, philosophers "aprioristically" reasoned from their proverbial armchairs

Do you think it would be more fair to write “philosophy [was dominated by] what is now called a classical account”? I’d be interested to learn why the sufficient & necessary paradigm came to be called a classical account, which seems to imply broader berth than Plato alone, but perhaps it was a lack of charity toward the ancients? (My impression is that the majority of modern analytic is still, more or less, chugging ahead with conceptual analysis, which, even if they would disavow sufficient and necessary conditions, seems more or less premised on such a view—take a Wittgensteinian, family resemblance view and the end goal of a robust and concise definition is impossible. Perhaps some analytic still finds value in the process, despite being more self-aware about the impossibility of some finally satisfying factoring of a messy human concept like “causality” or “art”?) One other regret is that this piece gives off the impression of a before/after specific to philosophy, whereas the search for a satisfying, singular definition of a term has plagued many fields, and continues to do so.

Like I said, I haven’t read Aristotle, but Eliezer’s claim seems at most half-wrong from a cursory read of Wikipedia and SEP on “term logic.” Perhaps I’m missing key complications from the original text, but was Aristotle not an originator of a school of syllogistic logic that treated concepts somewhat similarly to the logical positivists—as being logically manipulable, as if they were a formal taxonomy, with necessary and sufficient conditions, on whom deduction could be predicated? I’ve always read those passages in HGtW as arguing against naive definition/category-based deduction, and for Bayesian inference or abduction. I also must admit to reading quite a bit of argument-by-definition among Byzantine Christian philosophers.

Frustratingly, I cannot find "aprioristically" or “armchair” in Bishop either, and am gonna have to pull out my research notes from the archive. It is possible the PDF is poorly indexed, but more likely that line cites the wrong text, and the armchair frame is brought up in the Ramsey paper or similar. I’ll have to dive into my notes from last spring. Bishop does open:

> Counterexample philosophy is a distinctive pattern of argumentation philosophers since Plato have employed when attempting to hone their conceptual tools... A classical account of a concept offers singly necessary and jointly sufficient conditions for the application of a term expression that concept. Probably the best known of these is the traditional account of knowledge, "X is knowledge iff X is a justified true belief." The list of philosophers who have advanced classical accounts... would not only include many of the greatest figures in the history of philosophy, but also highly regarded temporary philosophers.

This is not, however, the same as saying that it was the only mode across history, or before Wittgenstein—ceded.

Glad to step away from the ancients and into conceptual engineering, but I’d love to get your take on these two areas—Aristotle’s term logic, and if there are specific pre-moderns you think identify and discuss this problem. From your original post, you mention Kripke, Kant, Epictetus. Are there specific texts or passages I can look for? Would love to fill out my picture of this discourse pre-Wittgenstein.

On the conceptual analysis/engineering points:

1. I have wondered about this too, if not necessarily in my post here then in posts elsewhere. My line of thought being, “While the ostensible end-goal of this practice, at least in the mind of many 20th C practitioners—that is, discovering a concise definition which is nonetheless robustly describes all possible instances of the concept which a native speaker would ascribe—is impossible (especially when our discourse allows bizarre thought experiments a la Putnam’s Twin Earth…), nonetheless, performing the moves of conceptual analysis is productive in understanding the concept space. I don’t think this is wrong, and like I semi-mentioned above, I’m on your side that Socrates may well have been in on the joke. (“Psych! There was no right answer! What have you learned?”) On the other hand, having spent some time reading philosophers hand-wringing over whether a Twin Earth-type hypothetical falsifies their definition, and they ought to start from scratch, it felt to me like what ought to have been non-problems were instead taking up enormous intellectual capital.

If you take a pragmatist view of concepts as functional human carvings of an environment (to the Ancients, “man is the measure of all things”), there would be no reason for us to expect our concepts’s boundaries and distinctions to be robust against bizarre parallel universe scenarios or against one-in-a-trillion probabilities. If words and concepts are just a way of getting things done, in everyday life, we’d expect them to be optimized to common environmental situations and user purposes—the minimum amount of specification or (to Continentals) “difference” or (to information theory) “information.”

I’m willing to cede that Socrates may have effectively demonstrated vagueness to his peers and later readers (though I don’t have the historical knowledge to know; does anyone?) I also think it’s probably true that a non-trivial amount of insight has been generated over many generations of conceptual analysis. But I also feel a lot of insight and progress has been foreclosed on, or precluded, because philosophers felt the need to keep quibbling over the boundaries of vagueness instead of stopping and saying, “Wait a second. This point-counterpoint style of definitions and thought experiments is interminable. We’ll never settle on a satisfying factoring that solves every possible edgecase. So what do we do instead? How do we make progress on the questions we want to make progress on, if not by arguing over definitions?” I think, unfortunately, a functionalist, pragmatist approach to concepts hasn’t been fleshed out yet. It’s a hard problem, but it’s important if you want to get a handle on linguistic issues. You can probably tell from OP that I’m not happy with a lot of the conceptual engineering discourse either. Many of it is fad-chasing bandwagoners. (Surprise surprise, I agree!) Many individuals seem to fundamentally misunderstand the problem—Chalmers, for instance, seems unable to perform the necessary mental switch to an engineer’s mindset of problem-solving; he’s still dwelling in definitions and “object-oriented,” rather than “functionalist” approaches—as if the dictionary entry on “engineering” that describes it as “analyzing and building” is authoritative on any of the relevant questions. Wittgenstein called this an obsession with generalizing, and a denial of the “particulars” of things. (Garfinkel would go on to talk at length about the “indexicality” or particulars.) Finding a way to deal with indexicality, and talk about objects which are proximate in some statistical clusterspace (instead of by sufficient and necessary models), or to effectively discuss “things of the same sort” without assuming that the definitional boundaries of a common word perfectly map to “is/is not the same sort of thing,” are all important starts.

2. I can’t agree more that “a good account of concepts should include how concepts change.” But I think I disagree that counterfactual arguments are a significant source of drift. My model (inspired, to some extent, by Lakoff and Hofstadter) is that analogic extension is one of the primary drivers of change: X encounters some new object or phenomenon Y, which is similar enough to an existing concept Z such that, when X uses Z to refer to Y, other individuals know what X means. I think one point in support of this mechanism is that it clearly leads to family-resemblance style concepts—“well, this activity Y isn’t quite like other kinds of games, it doesn’t have top-down rules, but if we call it a game and then explain there are no top-down rules, people will know what we mean.” (And hence, Calvinball was invented.) This is probably a poor example and I ought to collect better ones, but I hope it conveys the general idea. I see people saying “oh, that Y-things” or “you know that thing? It’s kinda like Y, but not really?” Combine this analogic extension with technological innovation + cultural drift, you get the analogic re-application of terms—desktop, document, mouse, all become polysemous.

I’m sure there are at least a couple other major sources of concept drift and sense accumulation, but I struggle to think of how often counterfactual arguments lead to real linguistic change. Can you provide an example? I know our culture is heavily engaged in discourses over concepts like “woman” and “race” right now, but I don’t think these debates take the character of conceptual analysis and counterfactuality so much as they do arguments of harm and identity.