Here's a pattern that doesn't work very well: a tragedy catches our attention, we point to statistics to show it's an example of a distressingly common problem, and we propose laws to address the issue. Except the event is rarely representative of the larger problem, and so these policy changes won't help much with the issues reflected in the statistics. Instead, we should combine the anger and passion the tragedy evokes with a deeper interpretation of the statistics to identify what changes we most need.

For example, with the recent Nashville school shooting a lot of people are giving statistics like how there were 600+ mass shootings and 51 school shootings in 2022, or how guns are now the largest cause of death for children. But let's look into the kind of events these statistics represent.

The Gun Violence Archive maintains a listing of mass shootings: incidents in which at least four people are shot. They link news stories for each, and while they're frustrating and depressing they're very rarely "someone senselessly shoots up an elementary school". Instead they're people fighting and one of them pulls out a gun, people arguing at a park and then escalating to shooting on the highway, or a targeted attack at a garage. In half of the incidents exactly four people are shot, since most shootings are fewer people and the cutoff is four.

Education Week maintains a listing of school shootings: incidents in which at least one person is shot on school property or a school bus. Looking over them they're again mostly not the kind that makes national news. Two teenagers fighting in the schoolyard and one of them has a gun, a drug deal between two armed people in a school parking lot escalates into a shooting, or an adult was shot in their car in the school parking lot after a basketball game.

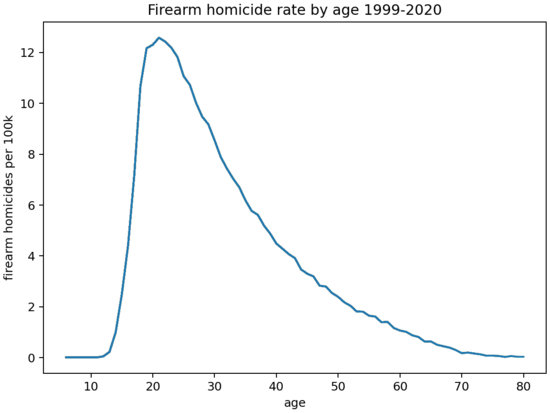

If you look at the Nashville school shooting, or others that have made especially large impacts nationally, they're attacks against younger kids. And hearing the "number one cause of death among children" statistic you might think this is common. But "children" here is being used literally to mean "under 18": 47% of those dying were 17, and 76% were 16 or 17. Only 18% were under 15:

Source: CDC, code

None of this is to minimize the suffering and loss these shootings represent: ten incidents in which four people die isn't better than one in which forty die, and someone dying at 17 isn't more acceptable than dying at 9. All of these deaths are too many. But if we're going to make things better, we need to target our responses to the common cases, and not the unusual ones that make the news.

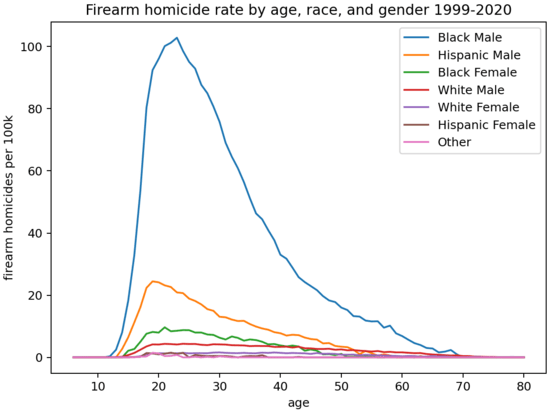

Here's the demographic breakdown:

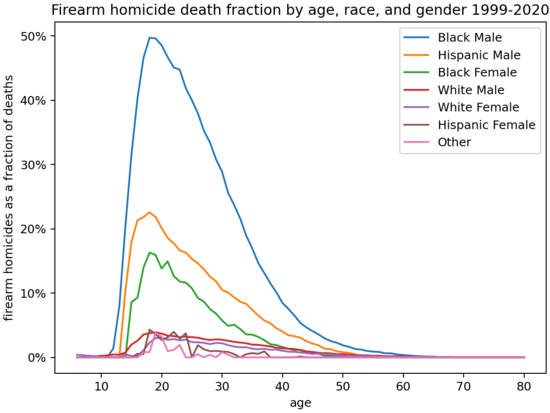

And as a proportion of deaths at each age:

That the impact of these shootings so strongly reinforces existing disadvantage makes the misplaced focus especially tragic.

Translating this into policies, the efforts to re-ban assault rifles don't make sense: gun homicides are overwhelmingly from handguns. Same with red flag laws, where a judge can order someone's guns confiscated, since most of the homicides are via illegally possessed guns which could already be confiscated. An approach of enforcing existing laws on handgun possession, however, making it less likely that teenagers and young adults who get into fights will be armed, is the kind of policy that fits the bulk of the problem, and sounds much more likely to make an impact.

I feel like the argumentation here is kinda misleading.

The post promises to discuss a pattern. It's obviously a culture-war-relevant pattern, and I can see a pretty good case for it being one where all the examples are going to be at least culture-war-adjacent. It's an important pattern, if true, so far that seems justified and worth worrying about how to improve on.

But then the post provides one example. Is it a pattern? If so, what are the other cases, and why doesn't the post concern itself with them? If the post is about the pattern of mistakes and how to address them, and why this is a thing to worry about in general, shouldn't there be more like 3+ examples?

The case made that gun violence is not being addressed well, and is conflating at least two different but related problems, seems quite strong. It's a good read, and the statistics presented make a strong case that we're not addressing it well. I liked the argument presented, and felt better informed for having read the post (note to self: I should probably dig a bit deeper on the statistics, since the conclusion is one I'm pretty sympathetic to). But if that's the argument the post is going to make, why isn't the title / intro paragraph something more like "we're not addressing the main causes of gun violence" or "mass shootings that make headlines aren't central examples of the problem" or something like that?

I assume that the gun violence example is one case of many, and that there are both general and specific lessons to be learned. I assume it would be possible to over-generalize from one example, so looking for common features and common failures would be instructive.

Overall, it felt like the post made several good points, but that the structure was a bit of a bait and switch.

Another example: using statistics about the frequency of abductions to argue that children should need to be pretty old before being on their own outside the house. Except a huge fraction of kidnapping is parental custody disputes, and if you're a parent making this decision you know whether that's a relevant concern.