There have been presistent rumors that electricity generation was somehow bottlenecking new data centers. This claim was recently repeated by Donald Trump, who implied that San Francisco donors requested the construction of new power plants for powering new AI data centers in the US. While this may sound unlikely, my research suggests it's actually quite plausible.

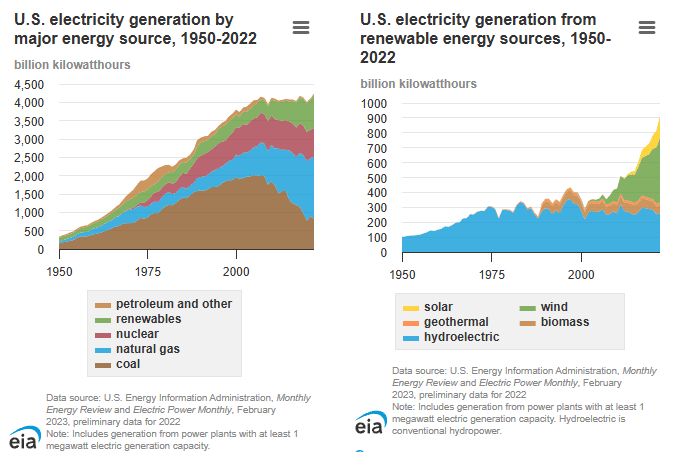

US electricity production has been stagnant since 2007. Current electricity generation is ~ 500 million kW. An H100 consumes 700 W at peak capacity. Sales of H100s were ~500,000 in 2023 and expected to climb to 1.5-2 million in 2024. "Servers" account for only 40% of data center power consumption, and that includes non-GPU overhead. I'll assume a total of 2 kW per H100 for ease of calculation. This means that powering all H100s produced to the end of 2024 would require ~1% of US power generation.

H100 production is continuing to increase, and I don't think it's unreasonable for it (or successors) to reach 10 million per year by, say, 2027. Data centers running large numbers of AI chips will obviously run them as many hours as possible, as they are rapidly depreciating and expensive assets. Hence, each H100 will require an increase in peak powergrid capacity, meaning new power plants.

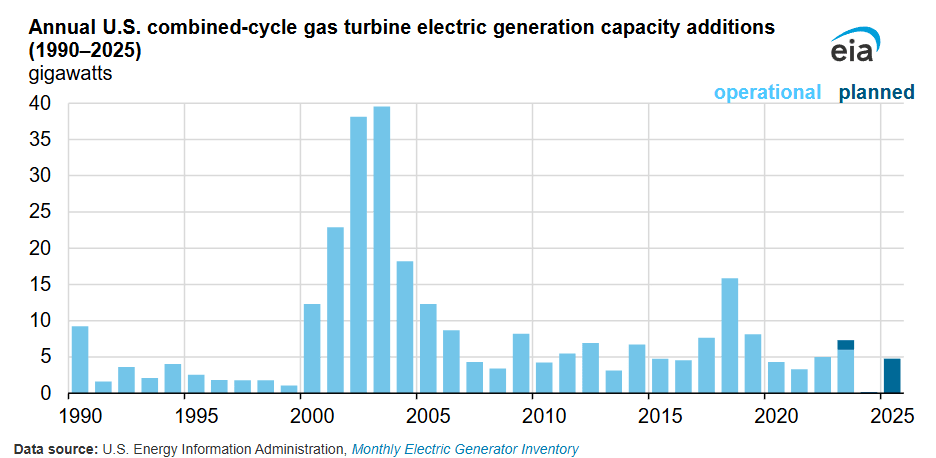

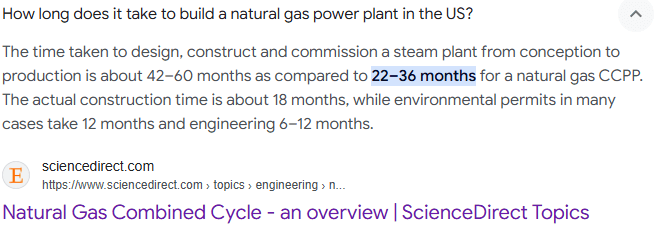

I'm assuming that most H100s sold will be installed in the US, a reasonable assumption given low electricity prices and the locations of the AI race competitors. If an average of 5 million H100s go online each year in the US between 2024 and 2026, that's 30 kW, or 6% of the current capacity! Given that the lead time for power plant construction may range into decades for nuclear, and 2-3 years for a natural gas plant (the shortest for a consistant-output power plant), those power plants would need to start the build process now. In order for there to be no shortfall in electricity production by the end of 2026, there will need to be ~30 million kW of capacity that begins the construction process in Jan 2024. That's about close to the US record (+40 million kW/year), and 6x the capacity currently planned to come online in 2025. I'm neglecting other sources of electricity since they take so much longer to build, although I suspect the recent bill easing regulations on nuclear power may be related. Plants also require down-time, and I don't think the capacity delow takes that into account.

This is why people in Silicon Valley are talking about power plants. It's a big problem, but fortunately also the type that can be solved by yelling at politicians. Note the above numbers are assuming the supply chain doesn't have shortages, which seems unlikely if you're 6x-ing powerplant construction. Delaying decommisioning of existing power plants and reactivation of mothballed ones will likely help a lot, but I'm not an expert in the field, and don't feel qualified to do a deeper analysis.

Overall, I think the claim that power plants are a bottleneck to data center construction in the US is quite reasonable, and possibly an understatement.

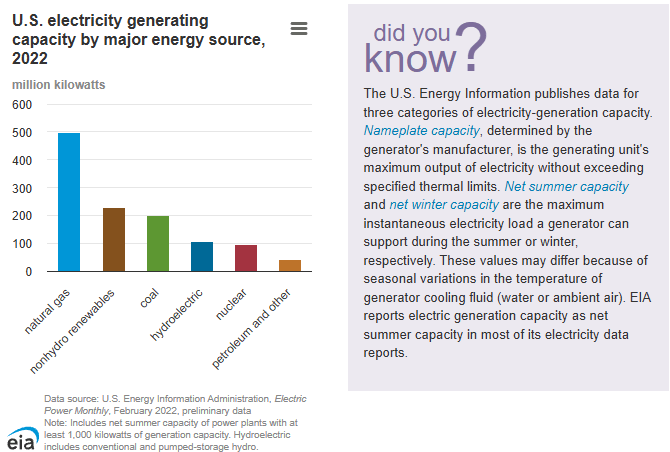

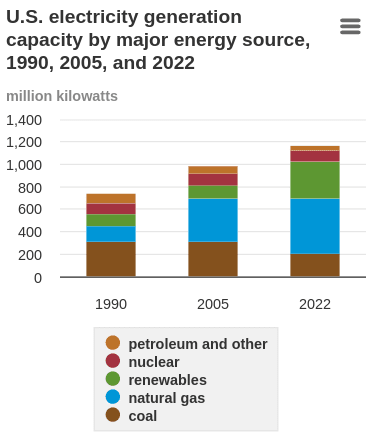

I doubt it (or at least, doubt that power plants will be a bottleneck as soon as this analysis says). Power generation/use varies widely over the course of a day and of a year (seasons), so the 500 GW number is an average, and generating capacity is overbuilt; this graph on the same EIA page shows generation capacity > 1000 GW and non-stagnant (not counting renewables, it declined slightly from 2005 to 2022 but is still > 800 GW):

This seems to indicate that a lot of additional demand[1] could be handled without building new generation, at least (and maybe not only) if it's willing to shut down at infrequent times of peak load. (Yes, operators will want to run as much as possible, but would accept some downtime if necessary to operate at all.)

This EIA discussion of cryptocurrency mining (estimated at 0.6% to 2.3% of US electricity consumption!) is highly relevant, and seems to align with the above. (E.g. it shows increased generation at existing power plants with attached crypto mining operations, mentions curtailment during peak demand, and doesn't mention new plant construction.)

Probably not as much as implied by the capacity numbers, since some of that capacity is peaking plants and/or just old, meaning not only inefficient, but sometimes limited by regulations in how many hours it can operate per year. But still.