I gave a five-minute talk talk for Ignite Long Now 2022. It’s a simplified and very condensed treatment of a complex topic. The video is online; below is a transcript with selected visuals and added links.

Humanity has had a pretty good run so far. In the last two hundred years, world GDP per capita has increased by almost fourteen times:

But “past performance may not be indicative of future results.” Can growth continue?

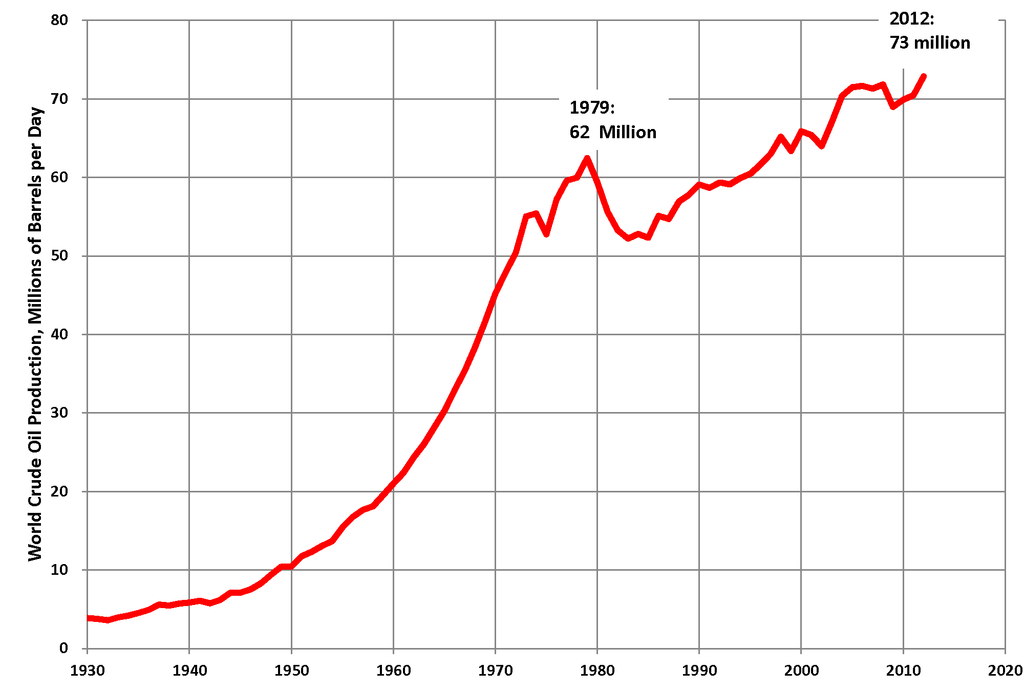

One argument against long-term growth is that we will run out of resources. Malthus worried about running out of farm land, Jevons warned that Britain would run out of coal, and Hubbert called Peak Oil.

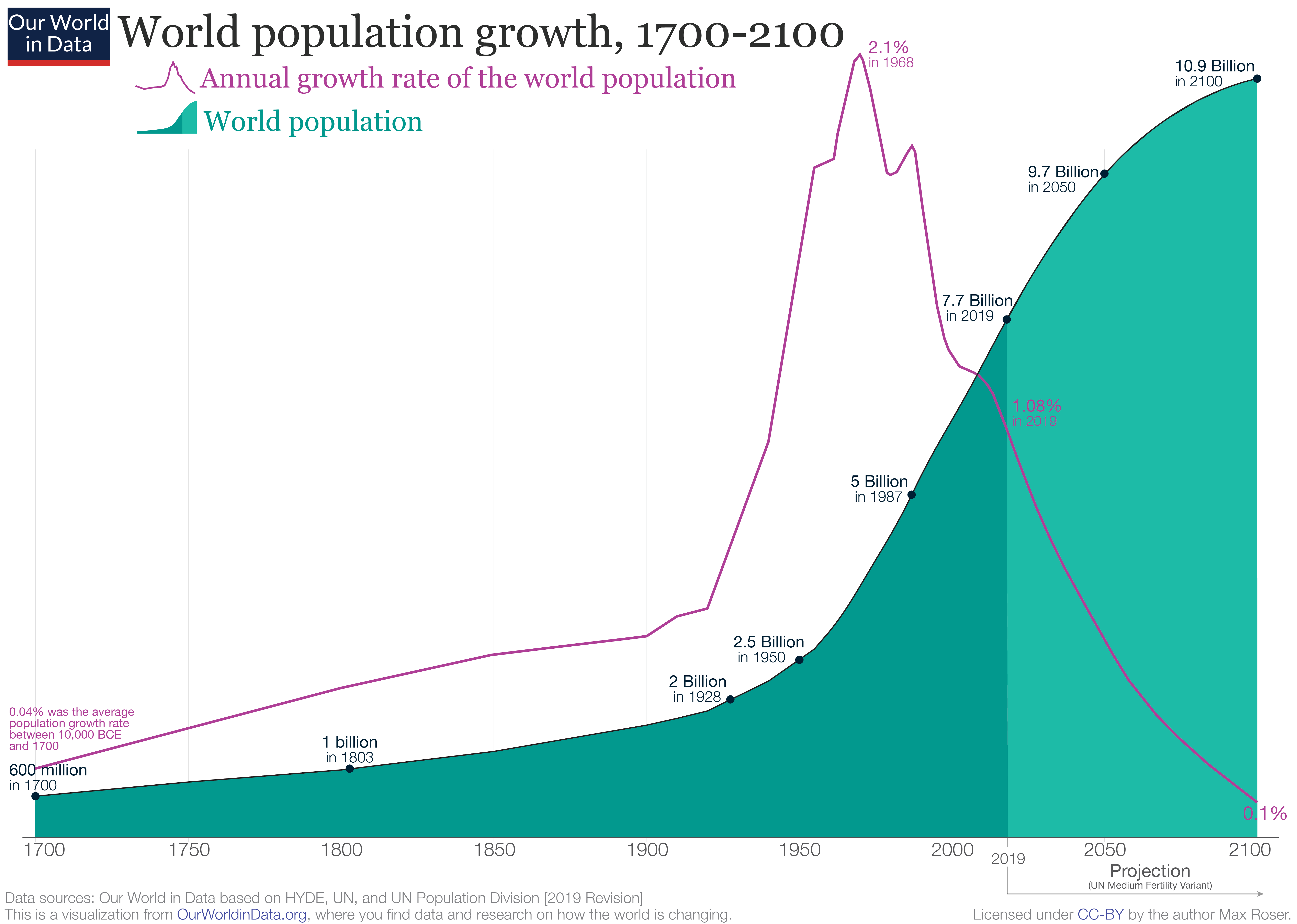

Fears of shortages lead to fears of “overpopulation”. If resources are static, then they have to be divided into smaller and smaller shares for more and more people. In the 1960s, this led to dire predictions of famine and depredation:

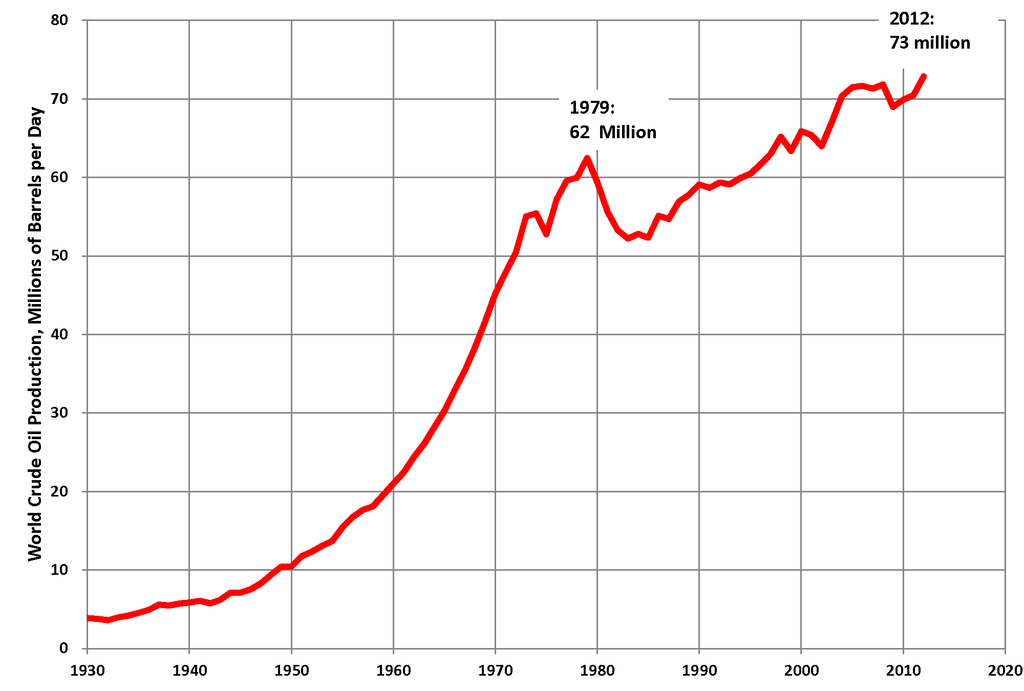

But predictions of catastrophic shortages virtually never come true. Agricultural productivity has grown faster than Malthus realized was possible. And oil production, after a temporary decline, recently hit at an all-time high:

One reason is that predictions of shortages are based on conservative estimates from only proven reserves. Another is that when a resource really is running out, we transition off of it—as, in the 1800s, we switched our lighting from whale oil to kerosene.

But the deeper reason is that there’s really no such thing as a natural resource. All resources are artificial. They are a product of technology. And economic growth is ultimately driven, not by material resources, but by ideas.

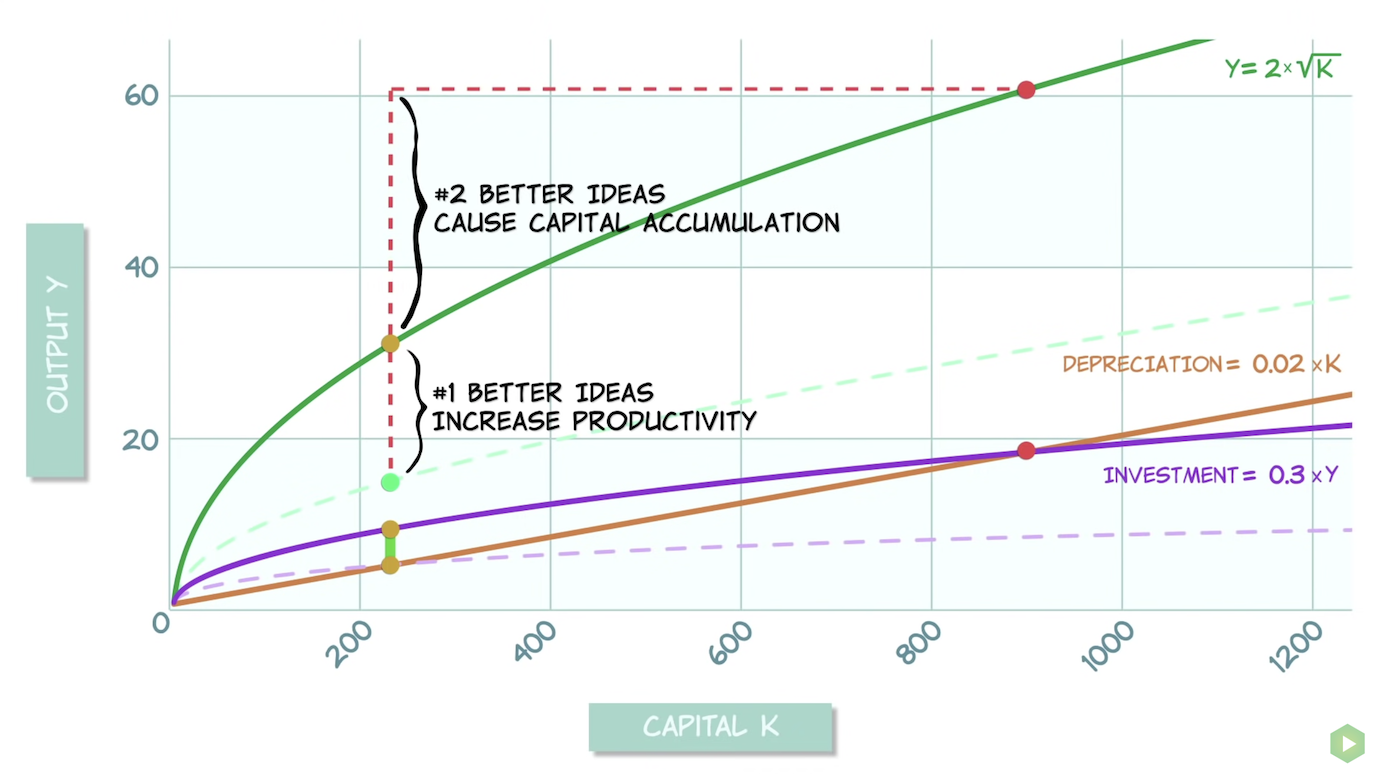

In the 20th century, the crucial role of ideas was confirmed by formal economic models. The economist Robert Solow was studying how output per worker increases as we accumulate capital, such as machines and factories. There are diminishing returns to capital accumulation alone. A single worker who is given two machines can’t be twice as productive. So if technology is static, output per worker soon stops growing:

But technology acts as a multiplier on productivity. This makes each worker more productive, and creates more headroom for capital accumulation:

So we can have economic growth if, and only if, we have technological progress.

How does this happen? Another economist, Paul Romer, pointed out the key feature of ideas: In economic terms, they are “nonrival”. Unlike a loaf of bread, or a machine, an invention or an equation can be shared by everyone. If we double the number of workers we have and double the machines they use, we will merely double their output, which is the same output per worker. But if we also double the power of technology, we will more than double output, making everyone richer. Physical resources have to be divided up, so as the population grows, the per-capita stock of resources shrinks. But ideas do not. The per-capita stock of ideas is the total stock of ideas.

So we won’t run out of resources, as long as we keep generating new ideas. But—will we run out of ideas?

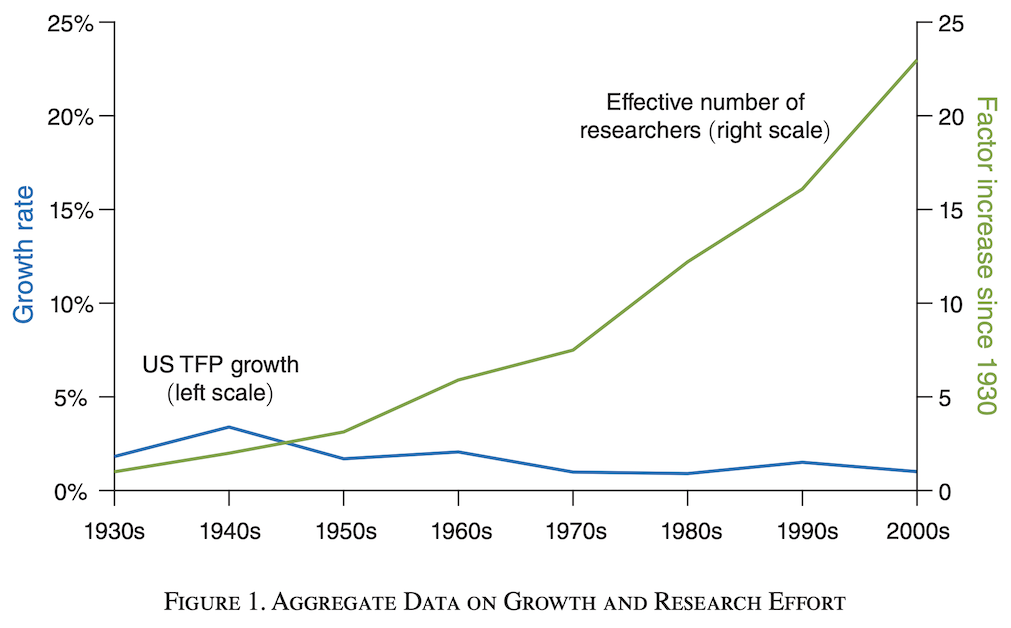

Romer assumed that the technology multiplier would grow exponentially at a rate proportional to the number of researchers. But another economist, Chad Jones, pointed out that in the 20th century, we have vastly increased R&D, while growth rates have been flat or even declining. This is evidence that ideas have been getting harder to find:

Does this mean inevitable stagnation? Maybe we have already picked all the low-hanging fruit. Maybe research is like mining for ideas, and the vein is running thin. Maybe inventions are like fish in a pond, and the pond is getting fished out. But notice that all these metaphors treat ideas like physical resources! And I think it’s a mistake to call “peak ideas”, just as it’s always been a mistake to call peak resources.

One reason, as Paul Romer pointed out, is that the space of ideas is combinatorially vast. The number of potential molecular compounds, or the number of possible DNA sequences, is astronomical. We have barely begun to explore.

And even as ideas get harder to find, we get better at finding them. As the population and the economy grow, we can devote more brains and more investment to R&D. And technologies like spreadsheets or the Internet make researchers more productive.

In fact, the greatest threat to long-term economic growth might be the slowdown in population growth:

Without more brains to push technology forward, progress might stall.

Now, that’s a problem for another time. But note that in five minutes we’ve gone from worrying about overpopulation to underpopulation. That’s because we’ve traded a scarcity mindset, where growth is limited by resources, for an abundance mindset, where it is limited only by our ingenuity.

Thanks to Brady Forrest and the Long Now Foundation for inviting me to speak.

I disagree, strongly. Not only do I believe this line of reasoning to be wrong, I believe it to be dangerously wrong. I believe downplaying and/or underestimating the role of energy in our economic system is part of why we find ourselves in the mess we're in today.

To reference Nate Hagens (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-xr9rIQxwj4)

We use the equivalent of 100 billion barrels of oil a year. Each barrel of oil can do the amount of work it would take 5 humans to do. There are 500 billion 'ghost' labourers in our society today.

(Back to me)

You cannot eat ideas. You cannot treat sewage with them. You cannot heat your home with them. You cannot build your home with them. You cannot travel across an ocean on them.

1000x0 is 0. Technology is a powerful multiplier, but 0 is 0.

You cannot build cold fusion power plants with ideas. You cannot conjure up the material resources or the skilled labour and energy inputs necessary to build them with ideas. (once again Nate Hagens - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O0pt3ioQuNc)

.... aaaand then there's the whole topic of renewables and the hidden costs and limitations thereof.

The only idea I have encountered that nullifies this reality is a superintelligent AI. The thing we're all so scared of, but simultaneously the only technology powerful enough to both harvest and utilize energy on scales beyond human ability. And also powerful enough to coordinate human activity such that Jeavons Paradox doesn't nullify the benefits (and, more generally, such that we don't waste such an insane amount of energy on stupid things).

And finally, re population:

Demographics, read about them - https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/40697556-the-human-tide

tl;dr Yes, Malthus was 'wrong'. He was wrong because it turned out that women with access to education and opportunity choose to have less children (there are exceptions, but not too many). Technology/ideas didn't save us from exponential population growth, it was a natural (i.e. not consciously considered, organized, enacted) change in behaviour.

I would like to think about this more, but thank you for posting this and switching my mind from System I to System II