Key points:

- Standardized assessments do not provide signals for the top ~10% of students.

- Education studies based on these poor signals lead to poor policies. For example, suspensions allegedly do not improve achievement among peers. However, the signal of "achievement" is "achieving credit in the class", which >80% of students already do. Thus, the conclusion is drawn from a change in, at most, the bottom quintile.

- This incentivizes teachers, schools, districts, and states to focus their resources where they can see any improvement, at the bottom.

- To correct public discourse and school policies, we have to fix the signals.

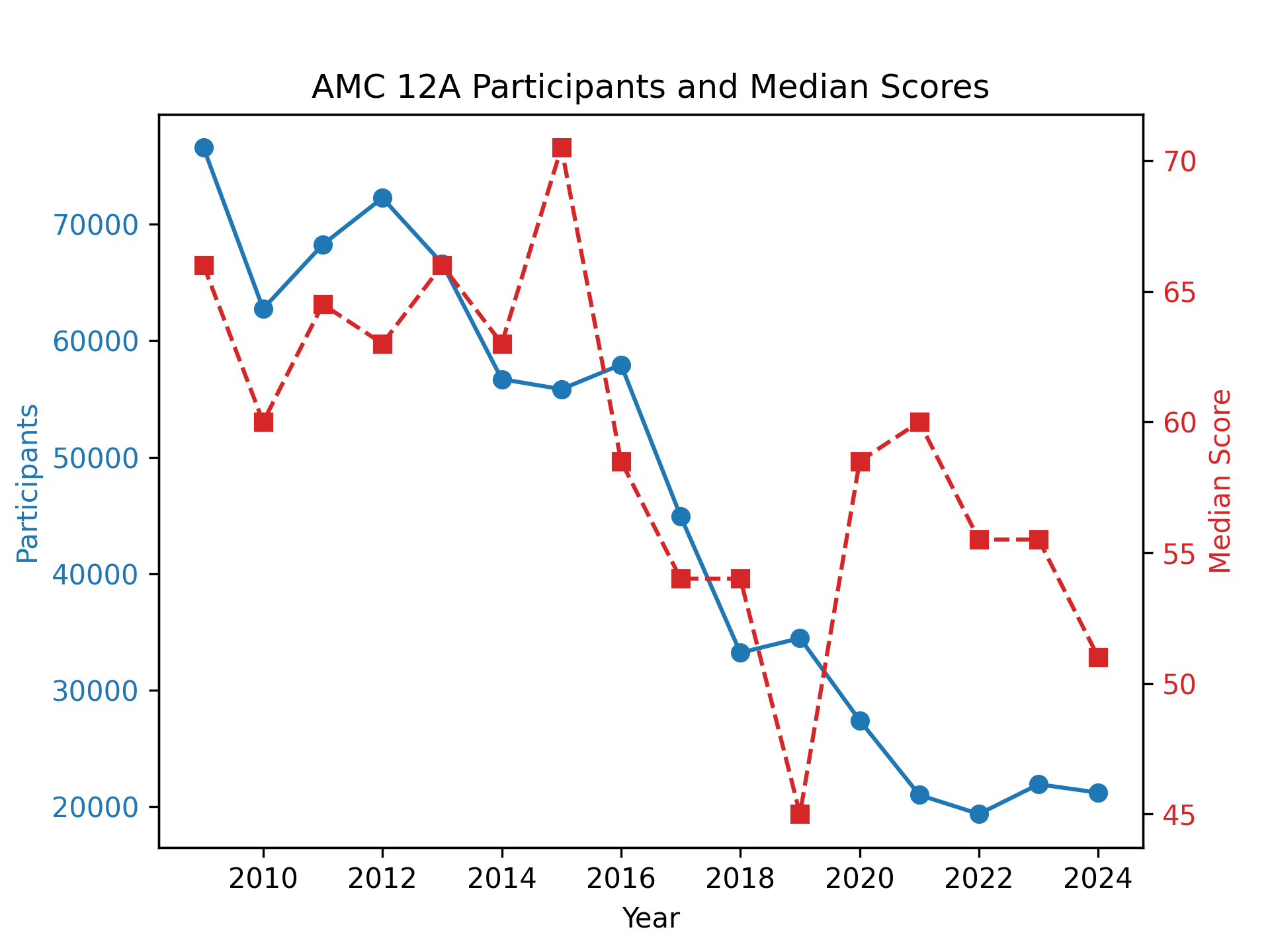

I graduated from high school three years ago, top of my class, "perfect" standardized test scores, and so on. More importantly, I participated in mathematics competitions, so I was very aware something was wrong with how I was being taught at school. I entered Kindergarten the year Common Core was introduced, though my first experience with it was in second grade, when I was told to "add numbers with the base-ten blocks". It was pointless—we already knew what numbers represented, and how to do arithmetic, so this didn't help us add faster or gain intuition. I attribute much of the recent nosedive in American Mathematics Contest participation and scores to Common Core.

The other, glaringly large contributor, is the elimination of gifted education programs. I prefer to call them the "patronage system", because historically rich patrons would sponsor promising students as an investment in the future. Nowadays, the government invests in all children's futures, but surprisingly invests less in promising students than average. There are still meritocratic scholarships to universities (and the rare specialized high school), but these have been relegated more and more to private charities over time.

Why? The simple, but incorrect, answer is that a corrupt ideology has infected the faculties of education. For example, I attended secondary school in a very conservative county—68% voted for Trump in the 2024 election—but even they had an infected board of education. Before my time, they would bus ~100 students to the local high school to take classes together. In 2015, due to financial concerns, the board discussed moving it to the middle school. They would still have their own cohort and take classes together, just in portables at the middle school instead of classrooms at the high school. From the 2016 meeting notes, parents were obviously "extremely concerned about any change to the program" and "fearful of losing what they currently have" (Provo School District Board Retreat Minutes, Sep. 2015). On the other hand, the main concerns from the board were "equity", "making sure disadvantaged students are not overlooked for testing", a "diverse population", "changing mindsets", and "public relations" (Feb. 2016). The parents were right to be concerned: once the program was eliminated from the high schools, a similar program never emerged at the middle schools.

Conservatives like to say that this is just what happens when your institution gets infected with the woke mind virus, but there's more to the story. Reading the minutes and discussing with so-called wokists, you'll find that they legitimately believe everyone ends up better off, and (more importantly) they have the studies to back it up. They'll acknowledge that lumping students of very diverse abilities into the same classroom marginally decreases the smartest students' scores, but is offset by a much larger increase from lower-scoring students who will become productive members of society. Or, they'll mention how social justice in the classroom prevents disaffected students from becoming even more disaffected, slowing the school-to-prison pipeline and decreasing the burden on taxpayers. They can quantify with numbers how each of these policies are net-positive for society. I had a rather interesting discussion with a leftist on Hacker News, and as he pointed out, "there's so much on this topic you're gonna have to switch your argument to explaining a conspiracy in educational research." So, how can it be that most of the smartest students going through the education system think something is wrong, that thousand-year-old patronage systems should be serving some purpose in society, or classrooms should be free from disruptions, when all the available evidence seems to prove otherwise?

The answer is that the studies do not pick up on the signals they claim to be looking for! For example, if you do an internet search for "do school suspensions improve outcomes?" you'll learn that "the findings underscore that suspending students does little to reduce future misbehavior for the disciplined students or their peers, nor did it result in improved academic achievement for peers or perceptions of positive school climate" ("School Suspensions Do More Harm than Good", Brenda Álvarez). If you actually read the study they're citing, you'll find that "academic achievement" means obtaining English or mathematics credit. Not only is that extremely easy to fudge, but 80% of students are graduating within four years, so the only signal they can possibly be getting are from the bottom quintile. That is hardly a measure of achievement! This is true of every single education study. Most are less egregious—for example, there is exactly one study that tries to measure the effect the "No Child Left Behind Act" (NCLB) had on high-achieving students, but they use the NAEP which only provides data up to the 90th percentile ("High-Achieving Students in the Era of NCLB", Thomas B. Fordham Institute). Gifted programs are typically comprised of the top 5% of students, so they cannot measure what they are looking for. It seems like this group put in an honest effort to find some signal, but the signal just does not exist in standardized assessments. Unfortunately, most researchers do not even try. A review of the literature from 2015 says:

Only one study specifically examined the achievement gap for students from low socioeconomic backgrounds (Hampton & Gruenert, 2008) despite NCLB’s stated commitment to improving education for children from low-income families. African American students were often mentioned in studies of general student achievement but none of the reviewed studies focused specifically on the effects of NCLB for this subgroup. Again, this is a curious gap in the research considering the law’s emphasis on narrowing the Black-White achievement gap. Other groups of students underrepresented in the research on NCLB include gifted students, students with vision impairments, and English proficient minority students. ("A Review of the Empirical Literature on No Child Left Behind from 2001 to 2010", pg. 25, Husband & Hunt)

The issue is twofold: (1) standardized assessments are not written to distinguish between the upper percentiles, and (2) most researchers are content with such poor signals, because it allows them to publish papers that align with their preconceived beliefs (or agenda). It's possible the examiners are also in on the conspiracy, but it seems more plausible they're just incompetent. I recall a question in sixth-grade asking me to add single-digit numbers with a number line and show my work, as if there was work to be shown; it seems grossly incompetent for that to make it onto a sixth-grade assessment (and I told them so, in lieu of showing work). The first step to fixing education is fixing the signals. Then, it will be much harder to draw faulty conclusions from poor signals, and the system should naturally improve over time.

For example, teachers are currently rated and given bonuses based on their students' improvement between beginning- and end-of-year assessments. However, I recall my fourth-grade gifted teacher complaining that many of her students scored perfectly on the pretest, and all scored close to perfect. It would be impossible to signal that she actually taught anything that year. You can then imagine what happens when the patronage system is eliminated: since students won't decline in ability over the year, every study will find that gifted students' scores stayed the same on the posttest, while the additional resources helped raise the average. It also creates a pernicious motivation for teachers and school districts to ignore their higher-scoring students, as the greatest gains in their metrics can be made at the bottom.

This is why that graph of AMC 12A participants and scores is so important to look at. National competitions are some of the only assessments we have that actually measure achievement, and it shows that there has been a dramatic decline in recent years. Fifteen years ago, there were over 30,000 students with a score above 60/150, while today a third that number score so high. Note that we should see some decline, as the tests have gotten harder over time, but not a two-thirds drop. Some politicians like to blame COVID-19 for every downturn, especially in education, but this trend began decades ago when policies were implemented based on faulty studies. If we fix this bug in the system, the trend will eventually reverse, though it may take another few decades.

Unfortunately, America doesn't have that time. China is quickly overtaking America in innovation because their students are more competent. Many figures on the right advocate for a school voucher system, "let the market figure things out", but that might take too long. Luckily, we can do a lot better than the market if we know better, and there are a few things that are known to be broken:

First, we need to reform teacher licensing. Usually states require secondary school teachers to get a passing score in a subject area examination, but then they also loosen this restriction anytime there is a shortage of teachers. It makes much more sense to just use the raw score to rank teacher candidates. That way, we can hire the good teachers and not hire (or fire) the bad. Also, the examinations need to include much more difficult questions near the end—the Praxis and the GRE mostly ask if you've seen the material before, not if you know how to apply it to new situations. My mental model of a good exam is closer to mathematics competitions, since, as the problem writers like to claim, it's all high school math, just tricky high school math. While it's true that knowing a subject is not the same as knowing how to teach it, it's a prerequisite too many teachers need to improve in.

Second, while I'm less sure about this, I also think we should do away with the student teaching requirements. It's essentially an unpaid internship, but even the bottom graduates in engineering expect a paid internship if they go into industry, and the people we want to be teachers can jump immediately to a six-figure salary. It's unappealing to recent graduates, and even less appealing to those in established careers. We need to decrease the transition energy if we want to quickly find good teachers.

Third, we need to make the actual profession more attractive. It's pretty difficult to attract teachers from a salary perspective—we want our top students to graduate into teaching, but the top 5% of earners make $300k/yr, which would wipe out the entire education budget. However, the current average of $70k/yr is too low. We can probably increase this to $100k/yr by decreasing administration and instructional support, but this will still only attract those already 'passionate' about teaching. Universities solve this problem by having an attractive work culture. Teaching, on the other hand, has a pretty horrible work culture. Allegedly 44% of teachers quit within their first five years (source). This is not very hard to fix. The most common complaints new teachers have is that their students are disruptive, their teaching is micromanaged, and they are being asked to teach ten different grade levels in the same classroom. The solution is to not obligate they babysit disruptive students, let them plan their own curriculum, and place students in appropriate classrooms.

Fourth, schools need to start "tracking" more officially. Primary schools already do this, but under the hood since it's taboo to talk about. Secondary schools have an opt-in system, where people choose to go in the regular, honors, or advanced placement tracks. The issue with under-the-hood or opt-in tracking is it misses a lot of students. If your parent doesn't know that so-and-so is the best third-grade teacher, you'll be stuck in the dumb class, or if you're unaware you can take calculus in ninth grade you might be held back. Having an official system, where everyone takes a test and are divided into classes by rank, is the most equitable solution and is easier on teachers. It's easier to plan lessons when students are closer in ability level, and the faster pace allows for shorter days. Tracking also allows your city or state magnet schools to reach out to promising students, rather than only getting parents in the know. And, finally, it would let the federal government create national boarding schools for the most talented students. It doesn't make sense to force parents to relocate to Fairfax County, Virginia just so their child can attend Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology instead of the local vaudeville show.

These are very broad measures, but to really improve fast there would need to be rapid experimentation in as many dimensions as possible. The free market could do this, but most parents rely on reputation to determine the "good schools", and that takes years to accumulate. I think a better approach is to directly perform experiments instead of relying on surveys. For example, within a county, have one school district increase teacher pay to $150k/yr and class sizes to 40, while another pays $50k/yr with smaller classes. Or, instead of buying textbooks from whichever group bribes the highest ("Judging Books by Their Covers", Surely You're Joking Mr. Feynman), have each class within the school follow a different curricula and see which one works the best. I think the tricky part is getting this done from a policy perspective. If you just eliminated the Department of Education, sure there would be some diversification of education, but the most similar schools would implement the most similar policies, which is disastrous for experimentation.

The median parent has median students for children. Therefore, interventions that seem good for the bottom 80% are much more popular than ones for the top %20 percent by simple population dynamics. So of course people care more about school for the middle 80 percent, since there is about an 80 percent chance that their children are there. At that point, arguing to the middle 80 wins elections, so we should expect to see it.

The current education system focuses almost exclusively on the bottom 20%. If we're expecting a tyranny of the majority, we should see the top and bottom losing out. Also, note that very few children actually have an 80% chance of ending up in the middle 80%, so you would really expect class warfare not a veil of ignorance if people are optimising specifically for their own future children's education.