Predictions of the future rely, to a much greater extent than in most fields, on the personal judgement of the expert making them. Just one problem - personal expert judgement generally sucks, especially when the experts don't receive immediate feedback on their hits and misses. Formal models perform better than experts, but when talking about unprecedented future events such as nanotechnology or AI, the choice of the model is also dependent on expert judgement.

Ray Kurzweil has a model of technological intelligence development where, broadly speaking, evolution, pre-computer technological development, post-computer technological development and future AIs all fit into the same exponential increase. When assessing the validity of that model, we could look at Kurzweil's credentials, and maybe compare them with those of his critics - but Kurzweil has given us something even better than credentials, and that's a track record. In various books, he's made predictions about what would happen in 2009, and we're now in a position to judge their accuracy. I haven't been satisfied by the various accuracy ratings I've found online, so I decided to do my own assessments.

I first selected ten of Kurzweil's predictions at random, and gave my own estimation of their accuracy. I found that five were to some extent true, four were to some extent false, and one was unclassifiable

But of course, relying on a single assessor is unreliable, especially when some of the judgements are subjective. So I started a call for volunteers to get assessors. Meanwhile Malo Bourgon set up a separate assessment on Youtopia, harnessing the awesome power of altruists chasing after points.

The results are now in, and they are fascinating. They are...

Ooops, you thought you'd get the results right away? No, before that, as in an Oscar night, I first want to thank assessors William Naaktgeboren, Eric Herboso, Michael Dickens, Ben Sterrett, Mao Shan, quinox, Olivia Schaefer, David Sønstebø and one who wishes to remain anonymous. I also want to thank Malo, and Ethan Dickinson and all the other volunteers from Youtopia (if you're one of these, and want to be thanked by name, let me know and I'll add you).

It was difficult deciding on the MVP - no actually it wasn't, that title and many thanks go to Olivia Schaefer, who decided to assess every single one of Kurzweil's predictions, because that's just the sort of gal that she is.

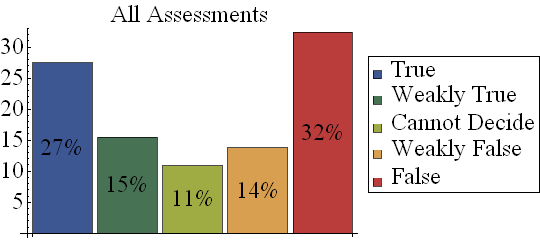

The exact details of the methodology, and the raw data, can be accessed through here. But in summary, volunteers were asked to assess the 172 predictions (from the "Age of Spiritual Machines") on a five point scale: 1=True, 2=Weakly True, 3=Cannot decide, 4=Weakly False, 5=False. If we total up all the assessments made by my direct volunteers, we have:

As can be seen, most assessments were rather emphatic: fully 59% were either clearly true or false. Overall, 46% of the assessments were false or weakly false, and and 42% were true or weakly true.

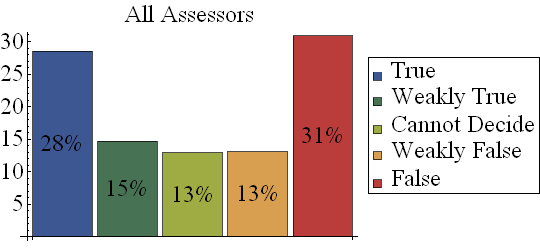

But what happens if, instead of averaging across all assessments (which allows assessors who have worked on a lot of predictions to dominate) we instead average across the nine assessors? Reassuringly, this makes very little difference:

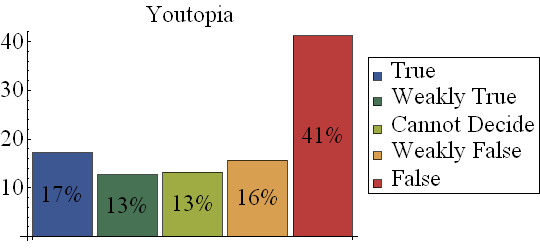

What about the Youtopia volunteers? Well, they have a decidedly different picture of Kurzweil's accuracy:

This gives a combined true score of 30%, and combined false score of 57%! If my own personal assessment was the most positive towards Kurzweil's predictions, then Youtopia's was the most negative.

Putting this all together, Kurzweil certainly can't claim an accuracy above 50% - a far cry from his own self assessment of either 102 out of 108 or 127 out of 147 correct (with caveats that "even the predictions that were considered 'wrong' in this report were not all wrong"). And consistently, slightly more than 10% of his predictions are judged "impossible to decide".

As I've said before, these were not binary yes/no predictions - even a true rate of 30% is much higher that than chance. So Kurzweil remains an acceptable prognosticator, with very poor self-assessment.

Carl is basically pointing out that assessing predictions is tricky business, because it's hard to be objective.

Here are a few points that need to be taken into account:

1. People have a lot to gain from being pessimistically defensive. It prevents them from being disappointed at some point in the future. The option for being pleasantly surprised, remains open. Being defensively pessimistic also prevents you from looking crazy to your peers. After all... who wants to be the only one in a group of 10 to think that by 2030 we'll have nanobots in our brains?

2. The poster assessed Kurzweil's predictions because he felt the need to do so. Why did he feel the need to do so? Is this about defensive pessimism?

3. It is safe to assume that a random selection of assessors would be biased towards judging 'False' for two obvious reasons. The first is the fact that they are uninformed about technology and simply aren't able to properly judge the lion's share of all predictions. The second is defensive pessimism.

4. Why is it judged that a 30% 'Strong True' is a weak score? In comparison to the predictions of futurologists before Kurzweil, 30% seems like an excellent score to me. It strikes me as a score that a man with a blurred vision of the future would have. But blurred vision of the future is all you can ever have. If the future were here, you'd be able to see it sharply in focus. Having blurred vision of the future is a real skill. Most people (SL0) have no vision of the future whatsoever.

5. How many years does a prediction have to be off in order for it to be wrong? How would you determine this number of years objectively?

6. Why did the assessors have to go with the 5-step-true-to-false system? Is that really the best way of assessing a futurologists predictions? I understand that we are a group of rational people here, but sometimes, you've gotta let go of the numbers, the measurements, the data and the whole binary thinking. Sometimes, you have to go back to just being a guy with common sense.

Take Kurzweil's long standing predictions for solar power, for example. He's been predicting for years that the solar tipping point would be around 2010. Spain hit grid parity in 2012 and news outlets are saying that the USA and parts of Europe will hit grid parity in 2013.

Calling Kurzweil's prediction on solar power wrong just because it's happening 2 to 3 years after 2010, is wrong in my opinion.

Kurzweil deserves some slack here. In the 1980s he predicted a computer would beat a human chess player in 1998. And that ended up happening a year earlier in 1997.

Kurzweil has blurry vision of the future. He might be a genius, but he is also just a human being that doesn't have anything better to go on than big data. Simple as that.

Instead of bickering about his predictions, we would do better to just look at the big picture of things.

Nanotech, wireless, robotics, biotech, AI... all of it is happening.

And be honest about Google's self driving car, which came out 2 years ago already: that was just an unexpected leap into the future right there!

I don't think Kurzweil himself saw self driving cars coming in 2011 already.

And to really hammer the point home, the self driving car had thousands of registered miles when it was introduced at the start of 2011. So it was probably already finished in 2010.

For all we know, the Singularity will occur in 2030. We just don't know.

Kurzweil has brought awareness to the world. Rather than sit around and count all the right and the wrong ones as the years pass by, the world would do better if it tried turning those predictions into self fullfilling prophecies.