Consider the following program:

f(n):

if n == 0:

return 1

return n * f(n-1)

Let’s think about the process by which this function is evaluated. We want to sketch out a causal DAG showing all of the intermediate calculations and the connections between them (feel free to pause reading and try this yourself).

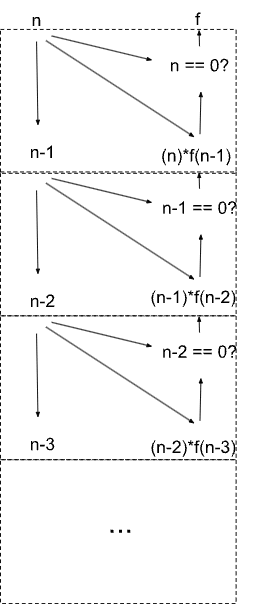

Here’s what the causal DAG looks like:

Each dotted box corresponds to one call to the function f. The recursive call in f becomes a symmetry in the causal diagram: the DAG consists of an infinite sequence of copies of the same subcircuit.

More generally, we can represent any Turing-computable function this way. Just take some pseudocode for the function, and expand out the full causal DAG of the calculation. In general, the diagram will either be finite or have symmetric components - the symmetry is what allows us to use a finite representation even though the graph itself is infinite.

Why would we want to do this?

For our purposes, the central idea of embedded agency is to take these black-box systems which we call “agents”, and break open the black boxes to see what’s going on inside.

Causal DAGs with symmetry are how we do this for Turing-computable functions in general. They show the actual cause-and-effect process which computes the result; conceptually they represent the computation rather than a black-box function.

In particular, a causal DAG + symmetry representation gives us all the natural machinery of causality - most notably counterfactuals. We can ask questions like “what would happen if I reached in and flipped a bit at this point in the computation?” or “what value would f(5) return if f(3) were 11?”. We can pose these questions in a well-defined, unambiguous way without worrying about logical counterfactuals, and without adding any additional machinery. This becomes particularly important for embedded optimization: if an “agent” (e.g. an organism) wants to plan ahead to achieve an objective (e.g. find food), it needs to ask counterfactual questions like “how much food would I find if I kept going straight?”.

The other main reason we would want to represent functions as causal DAGs with symmetry is because our universe appears to be one giant causal DAG with symmetry.

Because our universe is causal, any computation performed in our universe must eventually bottom out in a causal DAG. We can write our programs in any language we please, but eventually they will be compiled down to machine code and run by physical transistors made of atoms which are themselves governed by a causal DAG. In most cases, we can represent the causal computational process at a more abstract level - e.g. in our example program, even though we didn’t talk about registers or transistors or electric fields, the causal diagram we sketched out would still accurately represent the computation performed even at the lower levels.

This raises the issue of abstraction - the core problem of embedded agency. My own main use-case for the causal diagram + symmetry model of computation is formulating models of abstraction: how can one causal diagram (possibly with symmetry) represent another in a way which makes counterfactual queries on the map correspond to some kind of counterfactual on the territory? Can that work when the “map” is a subDAG of the territory DAG? It feels like causal diagrams + symmetry are the minimal computational model needed to get agency-relevant answers to this sort of question.

Learning

The traditional ultimate learning algorithm is Solomonoff Induction: take some black-box system which spews out data, and look for short programs which reproduce that data. But the phrase “black-box” suggests that perhaps we could do better by looking inside that box.

To make this a little bit more concrete: imagine I have some python program running on a server which responds to http requests. Solomonoff Induction would look at the data returned by requests to the program, and learn to predict the program’s behavior. But that sort of black-box interaction is not the only option. The program is running on a physical server somewhere - so, in principle, we could go grab a screwdriver and a tiny oscilloscope and directly observe the computation performed by the physical machine. Even without measuring every voltage on every wire, we may at least get enough data to narrow down the space of candidate programs in a way which Solomonoff Induction could not do. Ideally, we’d gain enough information to avoid needing to search over all possible programs.

Compared to Solomonoff Induction, this process looks a lot more like how scientists actually study the real world in practice: there’s lots of taking stuff apart and poking at it to see what makes it tick.

In general, though, how to learn causal DAGs with symmetry is still an open question. We’d like something like Solomonoff Induction, but which can account for partial information about the internal structure of the causal DAG, rather than just overall input-output behavior. (In principle, we could shoehorn this whole thing into traditional Solomonoff Induction by treating information about the internal DAG structure as normal old data, but that doesn’t give us a good way to extract the learned DAG structure.)

We already have algorithms for learning causal structure in general. Pearl’s Causality sketches out some such algorithms in chapter 2, although they’re only practical for either very small systems or very large amounts of data. Bayesian structure learning can handle larger systems with less data, though sometimes at the cost of a very large amount of compute - i.e. estimating high-dimensional integrals.

However, in general, these approaches don’t directly account for symmetry of the learned DAGs. Ideally, we would use a prior which weights causal DAGs according to the size of their representation - i.e. infinite DAGs would still have nonzero prior probability if they have some symmetry allowing for finite representation, and in general DAGs with multiple copies of the same sub-DAG would have higher probability. This isn’t quite the same as weighting by minimum description length in the Solomonoff sense, since we care specifically about symmetries which correspond to function calls - i.e. isomorphic subDAGs. We don’t care about graphs which can be generated by a short program but don’t have these sorts of symmetries. So that leaves the question: if our prior probability for a causal DAG is given by a notion of minimum description length which only allows compression by specifying re-used subcircuits, what properties will the resulting learning algorithm possess? Is it computable? What kinds of data are needed to make it tractable?

Nice example.

In this example, both scenarios yield exactly the same actual behavior (assuming we've set the parameters appropriately), but the counterfactual behavior differs - and that's exactly what defines a causal model. In this case, the counterfactuals are "what if we inserted a different resistor?" and "what if we adjusted the knob on the supply?". If it's a voltage supply, then the voltage -> current model correctly answers the counterfactuals. If it's a current supply, then the current -> voltage model correctly answers the counterfactuals.

Note that all the counterfactual queries in this example are physically grounded - they are properties of the territory, not the map. We can actually go swap the resistor in a circuit and see what happens. It is a mistake here to think of "the territory" as just the resistor by itself; the supply is a critical determinant of the counterfactual behavior, so it needs to be included in order to talk about causality.

Of course, there's still the question of how we decide which counterfactuals to support. That is mainly a property of the map, so far as I can tell, but there's a big catch: some sets of counterfactual queries will require keeping around far less information than others. A given territory supports "natural" classes of counterfactual queries, which require relatively little information to yield accurate predictions to the whole query class. In this context, the lumped circuit abstraction is one such example: we keep around just high-level summaries of the electrical properties of each component, and we can answer a whole class of queries about voltage or current measurements. Conversely, if we had a few queries about the readings from a voltage probe, a few queries about the mass of various circuit components, and a few queries about the number of protons in a wire mod 3... these all require completely different information to answer. It's not a natural class of queries.

So natural classes of queries imply natural abstract models, possibly including natural causal models. There will still be some choice in which queries we care about, and what information is actually available will play a role in that choice (i.e. even if we cared about number of protons mod 3, we have no way to get that information).

I have not yet formulated all this enough to be highly confident, but I think in this case the voltage -> current model is a natural abstraction when we have a voltage supply, and vice versa for a current supply. The "correct" model, in each case, can correctly predict behavior of the resistor and knob counterfactuals (among others), without any additional information. The "incorrect" model cannot. (I could be missing some other class of counterfactuals which are easily answered by the "incorrect" models without additional information, which is the main reason I'm not entirely sure of the conclusion.)

Thanks for bringing up this question and example, it's been useful to talk through and I'll likely re-use it later.