I am usually skeptical of technological inevitability, but this seems like a potentially good example. For decades, the New York City subway was a locally resisted technological temptation,[1] and a potential example of technological overhang.

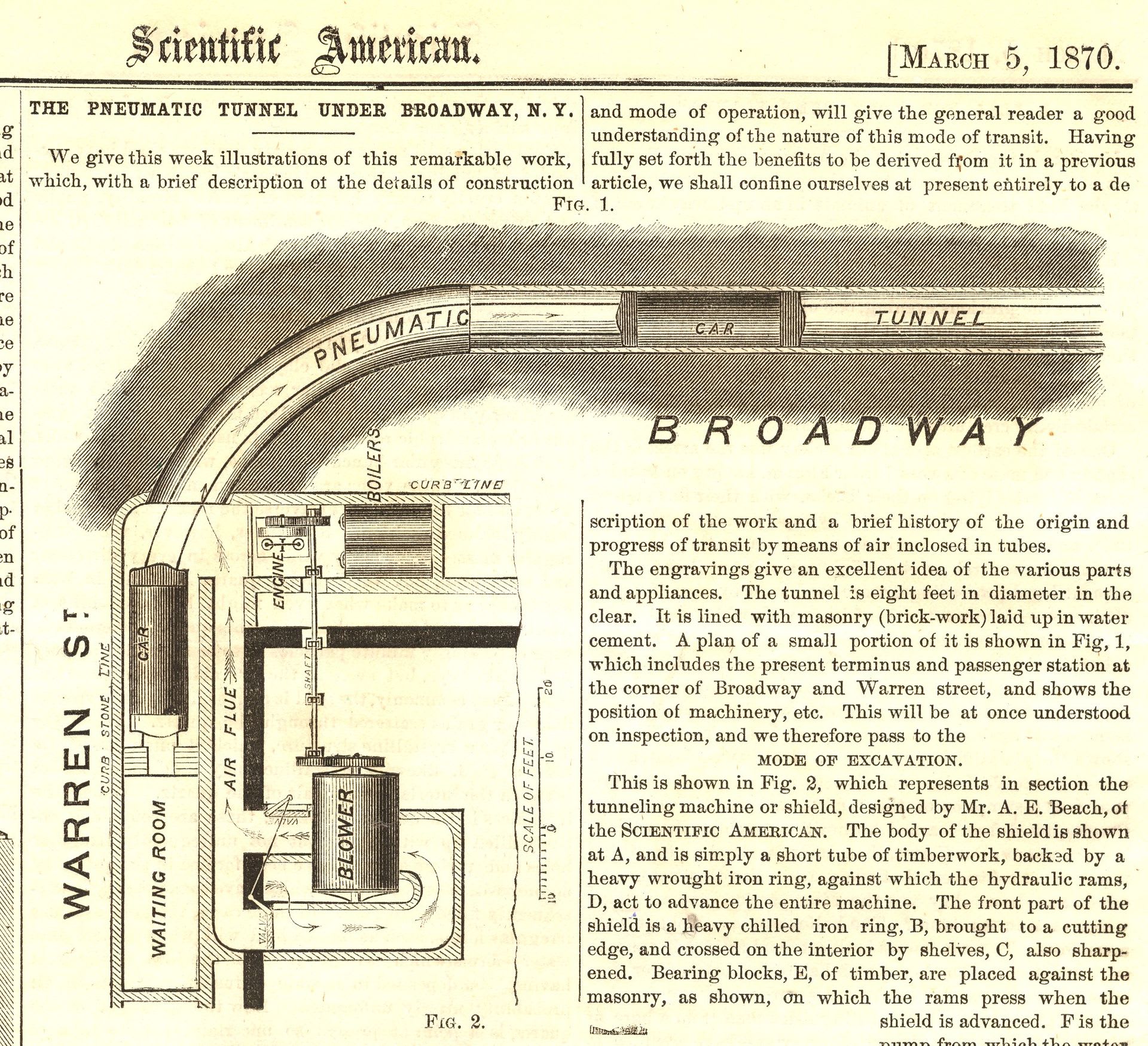

The 1866 example was effectively a tech demo for tech that wasn't good enough to use at all. Beach Pneumatic Transit is just a 300 foot long tube and you pump air on one side or the other with a steam engine.

It doesn't have any routing and it's difficult to see how to make this work at scale.

If you use the technology of the time, that's going to be boilers and steam engines per train, and they would fill the tunnels with coal smoke, which is quite deadly. (much more than just the carbon monoxide, a low concentration of it killed thousands of people.)

What you need is a big, heavy duty electric motor. Not a demo unit but something that can move a train.

And:

this allowed Sprague to use electric motors to invent the first electric trolley system in 1887–88 in Richmond, Virginia, the electric elevator and control system in 1892, and the electric subway with independently powered centrally-controlled cars. The latter were first installed in 1892 in Chicago by the South Side Elevated Railroad, where it became popularly known as the "L".

Conclusions: it looks like the time between "motor good enough for a subway" and "subway" was approximately 4 years, or about the earliest possible date.

New York's actions didn't create any kind of technological overhang because Chicago was doing it. Per the 'race' assumption, had New York failed to adopt the subway at all, instead of being 12 years late, NYC would have stopped growing, the Chicago Stock Exchange would be the largest, with Chicago the financial capital, and so on.

This doesn't look like it fits your reference class.

I chose the start date of 1866 because that is the first time the New York Senate appointed a committee to study rapid transit in New York, which concluded that New York would be best served by an underground railroad. It's also the start date that Katz uses.

The technology was available. London opened its first subway line in 1863. There is a 1.4 mi railroad tunnel from 1873 in Baltimore that is still in active use today. These early tunnels used steam engines. This did cause ventilation challenges, but they were resolvable. The other reasonable pre-electricity option would be to have stationary steam engines at a few places, open to the air, that pulled cables that pulled the trains. There were also some suggestions of dubious power mechanisms, like the one you described here. None of the options were as good as electric trains, but some of them could have been made to work.

This is not a global technological overhang, because there continued to be urban railroad innovation in other cities. It would only be overhang for New York City. This is a more restrictive definition of overhang than I used in my previous post, but it might still be interesting to see what happened with local overhang.

None of the options were as good as electric trains, but some of them could have been made to work.

Now that you've brought up other working systems, the question would be if the pre-electric subways ROIed. Yes there's cable driven streetcars in SF, as I recall switching cable is something the driver does. So that's a valid power mechanism.

Mitigations and inferior tech has costs. Higher ceilings, people passing out from CO exposure and heat, big ventilation fans that waste coal.

Were these costs enough to make the London subway unsustainable in an economic sense? The Baltimore one sounds too small to be viable.

Another thing you'd have to look at is what NYC residents are giving up. If a subway saves 20 minutes each way at that time from a 10 hour workday (Fair Labor Standards Act is 1944 limiting it to nominally 44 hours a week except for exempt), that's a cost of 6 percent to daily productivity.

Less because early subway networks only have partial coverage, so only the portion of the city's residents covered have a 6 percent delta in productivity.

This is such a small effect the historical data may not show anything. Many other factors would affect the economic performance of NYC and Chicago.

A hypothetical technology that made a 100% difference in productivity, or 1000%, would be far more costly to give up, and it might simply not be a viable choice at all. (unviable because it effectively makes the group "not giving in to temptation" cost 2x-10x as much to do any task, and they are selling goods and services to the global market. Would go broke fast. I did this analysis when looking at autonomous driving, and I realized that autonomous taxi and trucking firms could set their price to where their competition still using drivers loses money on every ride)

The London subway was private and returned enough profit to slowly expand while it was coal powered. Once it electrified, it became more profitable and expanded quickly.

The Baltimore tunnel was and is part of an intercity line that is mostly above ground. It was technologically similar to London, but operationally very different.

Introduction

The first serious attempt at building a subway in New York City occurred in 1866, following the end of the Civil War (1865) and the opening of the first subway in London (1863). The following decades saw a sequence of failed attempts, and the first subway in New York City would not begin operations until 1904.

When we consider how popular the subway was, even when it first opened, these failures are remarkable. Many of the important actors were indifferent or opposed, and those who supported building a subway were comically bad at coordinating. Only widespread, mostly decentralized public support was able to pressure different political and economic elites into finally cooperating.

The history of these efforts made me wonder whether the construction of a subway in New York City was inevitable. I am usually skeptical of technological inevitability, but this seems like a potentially good example. For decades, the New York City subway was a locally resisted technological temptation,[1] and a potential example of technological overhang.[2] The subway eventually succeeded despite a system that seemed structured to thwart it.

The main source I read about this history was:

All quotes or claims that are not cited come from this source. I have not investigated other sources in detail, but it seems to present a mainstream scholarly view of the history.

Why Did New York City Need A Subway?

By 1866, it seems inevitable that New York City would become one of the greatest world cities. It has an excellent harbor and a deep river heading inland. After the completion of the Erie Canal (1825), most of the Midwest’s international trade passed through New York. It has been the largest city in the US since the first census (1790),[5] and was among the 10 largest in the world by 1850.[6] Network effects would help it continue to grow. The New York Stock Exchange brought in large businesses, especially railroads. New York City was also a major destination for immigrants.[7]

Rapid transit was even more important for New York than for other great world cities. Manhattan is an island, and so New York City has fewer directions it can grow in than London, Paris, or Beijing. Manhattan is only two miles wide, and the central business district was at the end, in downtown.[8] People would commute much of the length of the island or across the rivers on ferries.

New York City had both surface and elevated trains before the subway was built. The surface trains (streetcars) had an extensive network, with many operators who eventually coalesced into the Metropolitan Traction Company. They could not travel faster than other traffic on the streets, so even an extensive network with good transfers wasn’t effective for longer trips. There were also some elevated lines (els) run by the Manhattan Railway Company. These were faster than the streetcars, but still had limited speed unless their steel viaducts were replaced by large, expensive, and more stable stone viaducts. Subways could go faster because they were built on solid ground. In practice, the subway was built with four tracks to provide both local and express service, while the els were built with only two tracks.[9]

In the absence of a subway, most of the new immigrants packed into extremely dense tennant houses in the Lower East Side of Manhattan. These slums were widely understood to be bad for the health, wealth, and moral progress of the people who lived in them. The hope was that the subway would allow poor immigrants to access the job opportunities of downtown Manhattan without having to live in the slums of the Lower East Side.[10]

Major Actors

The major actors involved in building the New York subway included:

Most infrastructure in the US had been built by private corporations or conglomerates, including New York’s streetcars and els. Most people assumed that some tycoon would be the one to build and operate the subway.

Most tycoons were uninterested in building the subway, because the construction would cost more than other transit possibilities. They believed that intercity rail was more likely to achieve an acceptable rate of return: at least 6% annually.

New York City’s Chamber of Commerce consisted of and represented the interests of the tycoons.

These people were mostly interested in improving the lives of the people living in the slums. The subway would provide a great public service, and would confirm New York’s preeminent place among the greatest cities in the world.

This group largely overlaps with the tycoons.[11] Magnanimously building great public works was popular among the business elites - especially if these public works could also make a decent rate of return. The tycoons who were interested in urban transit (which was a minority) had progressive tendencies.

The Chamber of Commerce also represented the reformers.

New York City’s local politics was dominated by Tammany Hall. Their base was largely poor immigrant communities, where they would exchange favors for votes. They were engaged in many instances of small-scale corruption and had earned a reputation of “lay[ing] the hand of spoliation upon the public funds.”

Occasionally, a coalition of all other political factions in the city could defeat the Tammany candidate for mayor, or a Tammany-backed mayor would act independently once in office. For the most part, dealing with the city government meant dealing with Tammany Hall.

Tammany Hall was mostly indifferent to whether a subway was built. All of the other actors believed that Tammany was incapable of running a railroad and, if they gained control over one, they would use it for petty patronage.[12]

Since the building of a railroad requires the exercise of state power (eminent domain), private companies would have to get a charter from the state legislature and sometimes approval from the state supreme court.

Most people in New York at the time lived in rural areas, so the state government was indifferent to whether New York City had a subway. They did not want to increase the power of their political rivals in the city, especially Tammany Hall.

They largely opposed the construction of a subway, because it would mean competition with their services. They had extensive economic and political connections across the city and could make things very difficult for anyone else interested in building or operating transit in New York City.

It is interesting that neither of them made a serious effort to build a subway themselves.[13] Controlling multiple forms of transit would have given them a more substantial monopoly.

There were both technical and financial reasons for their lack of interest. Financially, both companies had raised capital using ‘watered’ stock. This left them paying larger dividends to their shareholders than they could reasonably afford. Technically, they had other things they wanted to focus on: consolidating lines after purchasing formerly independent railroads, improving transfers, possibly adding a third set of rails to increase capacity, and electrification. Starting a whole new system seemed like a lot of additional work.[14]

Local businesses, especially along Broadway, did not want the disruption that subway construction would entail. These are the NIMBYs.[15] They were successful at making sure that the first subway would not run under the street through downtown which had the highest demand.

Basic Dynamics

The efforts to get a subway built occurred multiple times, with sixteen different companies being awarded a charter between 1864 and 1902. This is a large enough sample size to get a sense of the underlying dynamics at play.[16]

The impetus for subway construction typically came from progressives in the Chamber of Commerce, especially Abram Hewitt. They would draft a piece of legislation for the state legislature to consider. The legislation would create a commission empowered to grant a charter to a private company to build and operate the railroad. The commission would solicit bids[17] from potential tycoons or companies. The auction would fail to attract serious candidates, and the process would begin again.

The tycoons of the day were not interested in building the subway using their own money, because they did not believe that it would yield a significant rate of return. The city agreed to supply most of the capital, and so the city would legally own the subway. The construction would be done by the private company, and they would lease the railway and run the operations for an extended period of time.[18] The company would be obligated to repay the city at a fixed rate of return, but could keep the profits beyond that. The offer of public capital was supposed to incentivize some prominent businessman to build and run the subway, who had the necessary technical skills and would keep the subway out of the hands of Tammany Hall.

The details of the offered charter were determined by negotiations between the Chamber of Commerce, the state government, and city hall. These negotiations would determine who would be on the commission that reviewed the bids, how much capital would be provided publicly vs privately, what rate of return the city expected on its investment, and how long the lease would last. The result of the negotiations would end up being something that no prominent businessman would accept.

There would be some bidders. Sometimes, they would be people with insufficient financial backing or experience building railroads. Sometimes, they would be people interested in construction but not operations.[19] Sometimes, the charter would be awarded, and the bidder would reveal that they were a front for someone who wanted to ensure that the subway was not built.[20]

This system was not working, and it did not look like it was making progress towards working in the future either.

What Changed?

Mass public support eventually forced the various elite groups to cooperate.

In 1893, when the Chamber of Commerce proposed yet another subway bill to the state legislature, New York City’s labor unions submitted a rival bill,[21] which proposed a popular referendum. Although both groups wanted to see a subway built, the Chamber of Commerce opposed the referendum as a gateway to anarchy. The compromise bill that passed mostly followed the Chamber of Commerce’s proposal, but did include a referendum.

The referendum passed with over 75% of the vote. The Chamber of Commerce dominated commission reluctantly found itself with broad popular support.

The referendum did provide some additional constraints: the subway would have to run the entire length of Manhattan, and would charge 5¢ to go anywhere in the city. Despite these constraints, broad popular support was extremely useful.

After the state supreme court added some additional constraints,[22] a delegation of working men visited the commission and told them that “the working people were surprised to see the Commission ‘knocked out’ in one round against five judges … the law cannot be bigger than the will of the People.”

In 1898, the commission was still looking for offers, and was seriously looking at a proposal from the Metropolitan Traction Company.[23] The proposal was contrary to the letter of the law and especially to the spirit of the referendum: they asked for a perpetual franchise, no taxes until after the line had paid for itself, and 10¢ express services. The public was not happy: there were mass meetings throughout the city for weeks and almost every civic organization publicly opposed it, denouncing the Metropolitan, the commission, and Tammany together. Governor Theodore Roosevelt stepped in to stop the deal.

Mass public will had become strong enough that elite groups became willing to work together to build a subway.

The 1900 auction was attended by two bidders and the contract was awarded to John McDonald with (initially secret) backing from August Belmont II. McDonald had experience building railways in Baltimore, and Belmont had previously been involved in the management of the Long Island Rail Road. Both were tycoons, although not quite of the status the commission had originally intended. Both also had political connections to Tammany Hall. It is unclear what exactly was involved in the decision (or deal[24]) that gave McDonald & Belmont the contract, but the city had finally found people to build the subway who were willing and acceptable to most of the city’s elites.

The Metropolitan hadn’t quite given up. They convinced two financial institutions to renege on bonds they had agreed for McDonald. Belmont had to step in, providing much of the money himself and creating a company to sell (not watered) stock, in exchange for most of the profits.

Belmont’s company, the Interborough Rapid Transit Company, built the first subway line in New York City between 1900-1904, and soon afterwards extended it under the East River to Brooklyn.

By the time the line began construction, all of the technical details had been hashed out.[25] The route had been extensively litigated. Everyone knew that the best railroad for urban transit was underground, powered by “electricity,[26] and as near the surface as practicable.”

Conclusions

It seems like New York City tried to fail at building a subway system. There was some significant opposition, from the existing transit companies and (to a lesser extent) NIMBY business owners along Broadway. More important than outright hostility seems to be the indifference and conflict between various elite groups in New York.

Political leaders, both at Tammany Hall and the state legislature, didn’t care much about the project. Most of the efforts were instigated by civic-minded tycoons in the Chamber of Commerce. They proved unsuccessful at getting the political leaders to offer a contract that would convince prominent businessmen that this enterprise was worth pursuing. The resulting mess lasted for almost 40 years.

Public support for the subway seems both broad and deep. Katz does not describe how the public became so convinced, but I can guess at the outlines of a story. The problems of overcrowded slums and the difficulty of traveling across Manhattan would have been obvious. The public also had to be informed that better rapid transit was possible. Once they became aware, it is unsurprising that they supported it.

The public was eventually able to impose their will on the elite groups, offering more support than sometimes even the commission leading the efforts. They used a referendum, letters & delegations, mass meetings, and public statements by unrelated civic organizations to make their voice heard. This provided the pressure to get various elite groups to cooperate, until Tammany-friendly tycoons agreed to build the subway.

The result feels inevitable because of how it was pushed from below, in spite of decisions made by many individual actors. Elite indifference and opposition from a few key actors delayed the subway by a generation, but was not able to completely resist the public will.

Cover image: David Sagarin. Historic American Engineering Record. IRT East Side Line at 23rd Street. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division (1978). https://www.nycsubway.org/perl/show?7860.

Resisted Technological Temptations Project. AI Impacts Wiki. (Accessed Feb 7, 2023) https://wiki.aiimpacts.org/responses_to_ai/technological_inevitability/incentivized_technologies_not_pursued/resisted_technological_temptations_project.

The metric to look at would be something like the time it takes to travel from 59th Street to South Ferry. I expect that there is an archive of historical schedules for transit in New York City, including subway lines, elevated trains, streetcars, and stagecoaches. I have not done the investigation, but I expect that this archive would allow you to determine how this travel time changed in this era. This data might show growth as the els were built during the 1870s, then a plateau during the 1880s and 1890s, then rapid growth or a discontinuity when the subway opened in 1904.

Jeffrey Heninger. Are There Examples of Overhang for Other Technologies? AI Impacts Blog. (2023) https://blog.aiimpacts.org/p/are-there-examples-of-overhang-for.

Wallace B. Katz. The New York rapid transit decision of 1900: Economy, society and politics. Survey Number HAER-122, Historic American Engineering Record, National Park Service. (1978) p. 2-144. https://www.nycsubway.org/wiki/The_New_York_Rapid_Transit_Decision_of_1900_(Katz).

The Interborough Subway. Historic American Engineering Record, National Park Service, Department of the Interior, Washington, DC. 20240. (Accessed from nycsubway.org on Feb 15, 2024) https://www.nycsubway.org/wiki/The_Interborough_Subway_(Historic_American_Engineering_Record).

Philadelphia was larger in 1776, and Philadelphia’s city boundaries were smaller than New York’s, so New York would not be the largest metro area for a few more decades.

World’s Largest Cities, 1850. The Geography of Transport Systems. (Accessed Feb 7, 2023) https://transportgeography.org/contents/chapter8/transportation-urban-form/world-largest-cities-1850/.

Most large cities grow mostly because people within their country move from rural areas to urban areas. This is less the case in the US before 1900. Because of the Homestead Acts, many people would move to more rural areas in the West, while immigrants would move into American cities. There was some rural-to-urban migration in the US in the late nineteenth century, but it did not become the main driver of urbanization until the twentieth century.

Midtown’s central business district developed in the early twentieth century.

By the 1920s, the average speed of the streetcars was 8 mph, the average speed of the els was 14 mph, the average speed of local subway service was 15 mph, and the average speed of express subway service was 25 mph.

Clifton Hood. The Impact of the IRT on New York City. Survey Number HAER-122, Historic American Engineering Record, National Park Service. (1978) p. 145-206. https://www.nycsubway.org/wiki/The_Interborough_Subway_(Historic_American_Engineering_Record).

This hope does not seem to have been fulfilled when the first subway was completed. The original goal was to have the subway built out past the region with high land prices, so there could be better places for poor immigrants to live. By the time it was built, even the northern end of Manhattan had high enough land prices to prevent people moving there from the slums.

The Progressives of the early twentieth century who dominated the reform movement then would often be opposed to tycoons, but this is still the late nineteenth century.

The worries were both that the subway would be mismanaged, and that the revenue it generated would be used to feed the Tammany political machine. Some specific things to be concerned about included hiring based on political connections, payroll padding, not enforcing fares for favored groups, neglecting maintenance, and (once the subway became multi-lined) poor scheduling leading to conflicts between trains. It’s not clear whether these concerns would have been realized, but later generations of city officials in New York could be extremely incompetent.

They would sometimes submit subway proposals, but the goal of these proposals was to prevent anyone else from building a subway.

The technical problems probably could have been made manageable. The company that did build the subway bought the els in Manhattan to strengthen their monopoly while the subway was still under construction.

‘NIMBY’ is an acronym for ‘Not In My BackYard.’ They oppose development in their local area, not because they dislike development, but because they do not want their particular neighborhood to change character.

I am describing the entire process for a typical attempt. When an attempt failed, it would go back to an earlier stage, but sometimes not all the way back to the beginning. There were fewer pieces of legislation and commissions than there were auctions and charters.

The first rendition did not have bids. The plan was to ask Vanderbilt, who had recently built some intercity rail into New York City, to build a subway. He refused, and so the commission failed.

The els in Manhattan had a 999 year lease. The subway ended up with a 50 year lease. In 1940, the city would end up purchasing both private subway companies that were then operating in New York City, even though their leases were not up yet.

This is unacceptable because it might lead to a situation where the city government, and therefore Tammany Hall, ends up in charge of operating the subway.

The city would not give them the money in this case, but it would still delay the subway for a few more years.

The immediate reason that labor unions submitted a bill was because of a recent economic downtown, the Panic of 1893. Subway construction would provide jobs for their unemployed members. The labor unions had not submitted bills during previous economic downturns, like the much more severe Panic of 1873. This bill is itself evidence of increasing public support for a subway independent of the reformers in the Chamber of Commerce.

The first subway would not be built under Broadway and the total cost for the line extending the length of Manhattan had to be clearly less than $50 million.

It’s not clear whether the Metropolitan Traction Company would have gone through with their offer, or whether they would return the city’s money and declare it impossible. This at least seems to have been more real of a proposal than some of their earlier efforts.

Later muckrakers would claim that this decision was predetermined by a backroom deal between the Chamber of Commerce and Tammany Hall, although everyone involved denied this.

A description of the debates over the technical details of the subway can be found in Part 1 of another article in the series:

Charles Scott. Design and Construction of the IRT: Civil Engineering. Survey Number HAER-122, Historic American Engineering Record, National Park Service. (1978) p. 207-282. https://www.nycsubway.org/wiki/Design_and_Construction_of_the_IRT:_Civil_Engineering_(Scott).

If the subway had been built much earlier, it likely would have been steam powered. Ventilation for coal burning locomotives in tunnels was difficult, but it had been done on London’s subway.