You are one of the best long-range snipers in the World. You often have to eliminate targets standing one or two miles away and rarely miss. Crucially, this is not because you are better than others at aligning the scope of your rifle with the target’s head before taking the shot. Rather, this is because you are better at accounting for the external factors that will influence the bullet’s direction (e.g., the wind, gravity, etc.). Estimating these external factors is crucial for your success. One day, you are on a roof with binoculars, looking at a building four miles away that you and your team know is filled with terrorists and their innocent children. Your superior is beside you, looking in the same direction. Your mission is to inform your allies closer to the building if you see any movement. After a long wait, the terrorist leader comes out, holding a child close to him. He knows ennemies might be targetting him and would not want to hurt the kid. They are hastily heading towards another building nearby. You grab your radio to inform your allies but your superior stops you and hands you your sniper. “He’s so exposed. This is a golden opportunity for you.” she says. “I reckon we’ve got two minutes before they reach the other building. Do you think you can get him?“. You know that your superior generally accepts risking the lives of innocents but only if there are more bad guys than innocents killed, in expectation. “Absolutely not.” you respond. “We are four miles away! I’ve never taken a shot from this far. NO ONE has ever hit a target from this far. I’m just as likely to hit the kid.” Your superior takes a few seconds to think. “You always say that where the bullet ends up is the result of an equation: ‘where you aim + the external factors’, right?” she says. “Yes,” you reply nervously “And I have no idea how to account for the external factors from that far. There are so many different wind layers between us and the target. The Earth’s rotation and the spin drift of the bullet matter also a hell of a lot from this distance. I would also have to factor in the altitude, humidity, and temperature of the air. I don’t have the faintest idea what this sums up to overall from this far! I’m clueless. I wouldn’t be more likely to get him and not the kid if I were to shoot with my eyes closed.” Your superior turns her head towards you. “Principle of indifference,” she says. “You have no clue how external factors will affect your shot. You don’t know if they tell you to aim more a certain way rather than another. So simply don’t adjust your shot! Aim at this jerk and shoot as if there were no external factors! And you’ll be, in expectation, more likely to hit him than the kid.”

I'm curious whether people agree with the superior. Do you think applying the POI is warranted, here? Any rationale behind why (not)?

EDIT: You can assume the child and the target cover exactly as much hittable surface area if you want, but I'm actually just interested in whether you find the POI argument valid, not in what we think the right strategic call would be if that was a real-life situation. (EDIT 2:) This is just a thought experiment aiming at assessing whether applying POI makes sense in situations of complex cluelessness. No kid is going to get killed in the real world because of your response. :)

Oh… wait a minute! I looked up Principal of Indifference, to try and find stronger assertions on when it should or shouldn’t be used, and was surprised to see what it actually means! Wikipedia:

>The principle of indifference states that in the absence of any relevant evidence, agents should distribute their credence (or "degrees of belief") equally among all the possible outcomes under consideration. In Bayesian probability, this is the simplest non-informative prior.

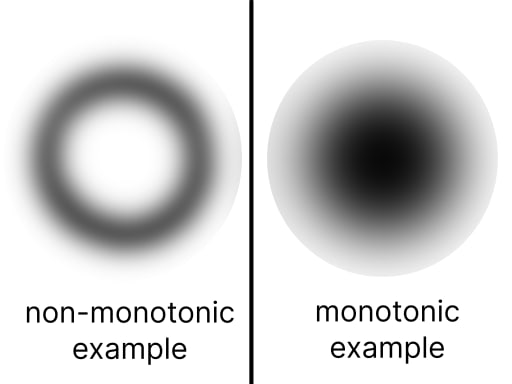

So I think the superior is wrong to call it “principle of indifference”! You are the one arguing for indifference: “it could hit anywhere in a radius around the targets, and we can’t say more” is POI. “It is more likely to hit the adult you aimed at” is not POI! It’s an argument about the tendency of errors to cancel.

Error cancelling tends to produce Gaussian distributions. POI gives uniform distributions.

I still think I agree with the superior that it’s marginally more likely to hit the target aimed for, but now I disagree with them that this assertion is POI.