Against LLM Reductionism

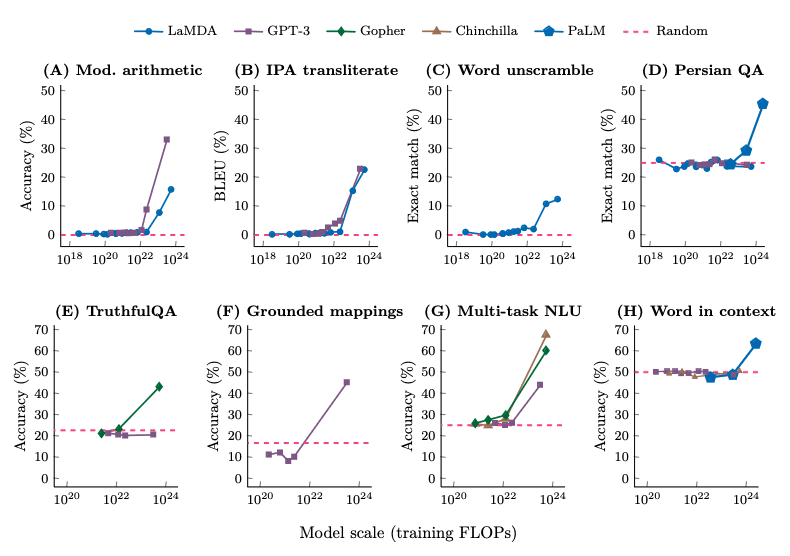

Summary * Large language models (henceforth, LLMs) are sometimes said to be "just" shallow pattern matchers, "just" massive look-up tables or "just" autocomplete engines. These comparisons amount to a form of (methodological) reductionism. While there's some truth to them, I think they smuggle in corollaries that are either false or at least not obviously true. * For example, they seem to imply that what LLMs are doing amounts merely to rote memorisation and/or clever parlour tricks, and that they cannot generalise to out-of-distribution data. In fact, there's empirical evidence that suggests that LLMs can learn general algorithms and can contain and use representations of the world similar to those we use. * They also seem to suggest that LLMs merely optimise for success on next-token prediction. It's true that LLMs are (mostly) trained on next-token prediction, and it's true that this profoundly shapes their output, but we don't know whether this is how they actually function. We also don't know what sorts of advanced capabilities can or cannot arise when you train on next-token prediction. * So there's reason to be cautious when thinking about LLMs. In particular, I think, caution should be exercised (1) when making predictions about what LLMs will or will not in future be capable of and (2) when assuming that such-and-such a thing must or cannot possibly happen inside an LLM. Pattern Matchers, Look-up Tables, Stochastic Parrots My understanding of what goes on inside machine learning (henceforth, ML) models, and LLMs in particular, is still in many ways rudimentary, but it seems clear enough that, however tempting that is to imagine, it's little like what goes on in the minds of humans; it's weirder than that, more alien, more eldritch. As LLMs have been scaled up, and more compute and data have been poured into models with more parameters, they have undergone qualitative shifts, and are now capable of a range of tasks their predecessors couldn't even gras

I wrote a post forecasting Chinese compute acquisition in 2026. The very short summary is that I expect about 60% to be legally imported NVIDIA H200s, with domestically produced Huawei Ascends accounting for about 25%, and the remainder being smuggled AI chips and Ascends illegally fabricated outside China via proxies.

While China likely produces GPU dies in quite large quantities, it is likely bottlenecked by an HBM shortage, which limits the total number of Ascend 910Cs and other AI chips that can actually be assembled. I do expect domestic production to grow substantially in 2027 and 2028, as CXMT ramps up HBM production.

In total, I expect China to acquire about 320,000 B300-equivalents (90%... (read more)