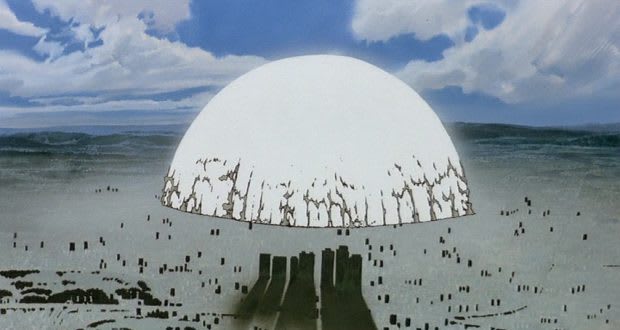

Why does anime often feature giant, perfectly spherical sci-fi explosions?? Eg, consider this explosion from the movie "Akira", pretty typical of the genre:

These seem inspired by nuclear weapons, often they are literally the result of nuclear weapons according to the plot (although in many cases they are some kind of magical / etc energy). But obviously nuclear weapons cause mushroom clouds, right?? If no real explosion looks like this, where did the artistic convention come from?

What's going on? Surely they are not thinking of the spherical fireball that only occurs for a handful of milliseconds after a nuclear detonation?? Is it just that spheres are easy to draw??

The answer seems to be that large explosions in humid air (like, say, Japan) cause exactly this sort of rapidly-expanding spherical pulse, as shockwaves cause a pulse of condensation. Check out these videos of the (non-nuclear) 2020 Beirut explosion; it's a dead ringer for the matching scene in Akira. Here is an especially far-away view of the Beirut explosion where you can see how the shockwave interacts with nearby clouds in an interesting way.

The USA's cultural image of nuclear explosions comes mostly from early nuclear tests conducted in sunny Nevada, which only generates dry mushroom clouds. (Hence also, perhaps, our cultural associations of a post-nuclear-war world as a dry, desiccated wasteland like those of Fallout or Mad Max?) In Japan, I imagine the more salient reference points would have been 1. eyewitness descriptions of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which happened on partly cloudy & overcast days and presumably looked more like the Beirut video (but bigger), and 2. the later tests of hydrogen bombs at Bikini Atoll, which became somewhat of an international incident regarding the deaths of some Japanese fishermen, and whose explosions similarly had an "expanding white sphere" look to them.

(For a particularly HD, live-action hollywood representation of the spherical-anime-explosion motif, see this scene from Pacific Rim, which interprets the anime motif through a kind of confused mix of vacuum cavitation in water, the back-and-forth wind effects seen in lots of nuclear test footage, and the first-few-milliseconds spherical fireball of a nuclear explosion.)

Thank you for your attention to this matter.

Non-zero, of course, in the same sense that credit card companies tolerate a non-zero amount of fraudulent transactions as part of doing business. And I agree that the right amount of resources to spend on fare enforcement will be different for each transit system, depending on all kinds of particular circumstances. But I would guess that for most transit systems, "let's help the poor by cutting back on fare evasion" would overall be a much worse use of marginal resources than "let's help the poor by offering free or discounted fare cards or giving them fare credits", or perhaps "let's help everyone by slightly expanding service frequency / coverage".

Eg, grocery stores tolerate some amount of "shrinkage" (people stealing the food) according to whatever maximizes profits. If grocery stores were run by the government and were willing to run at a loss in order to promote greater overall social welfare, I wouldn't support a policy of "let's just roll back our shrinkage enforcement and let people steal more food". I would instead support giving poorer people something like expanded EBT food stamp credits. (And, per kelsey, signing up for such a program should be made simpler and more rational!)

Tolerating a high amount of fare evasion also means letting some very disorderly people into the system, which makes the experience worse for all the actual paying users of the system. So it is not always "near zero marginal cost" to let other people free-ride (even outside of busy, congested times).

For an example targeting rich people instead of the poor: I think we should lower income and corporate taxes (which discourage productive work) and replace the lost revenue with pigovian taxes (ie a carbon tax, sin taxes, etc) plus georgist land taxes. And, for the purposes of this conversation, say that I support lowering taxes overall, in a way that would disproportionately benefit rich people and corporations. But I am totally against severely rolling back IRS enforcement against tax cheats (as is currently happening), because this runs into all kinds of adverse selection problems where you're now disproportionately rewarding (probably less economically productive) cheats, while punishing (probably more productive) honest people.

Surely the most important distinction is that normal price discrimination is usually based on trying to infer a customer's willingness to pay (based on how wealthy they are, how much they want the product, etc). Versus fare evasion is also heavily based in how willing someone is to lie / cheat / otherwise break the rules. So, tolerating fare evasion is a form of "price discrimination" that's dramatically corrosive to societal trust and other values, much moreso than any normal kind of price discrimination -- effectively a disproportionate tax on honorable law-abiding people. See Kelsey piper's article https://www.theargumentmag.com/p/the-honesty-tax

The impression I got from Ngo's post is that:

- assorted varieties of gradual disempowerment do seem like genuine long term threats

- however, by the nature of the idea, it involves talking a lot about relatively small present-day harms from AI

- therefore gradual disempowerment is highly at-risk of being coopted by people who mostly just want to talk about present day harms, distracting from both AI x-risk overall and even perhaps from gradual-disempowerment-related x-risk

Oh, I think they probably try to adapt in a variety of ways to be more hospitable & compatible with me when I'm around. (Although to a certain extent, maybe I'm more weird (less "normie") than they are, plus I'm from a younger generation, so the onus is more on me socially to adapt myself to their ways?) But the focus of my comment was about the ways that I personally try to relate to people who are quite different from me. So I didn't want to dive into how they might find it difficult or annoying being around me and how they might deal with this (though I'm sure they do find me annoying in some ways -- another reason to be grateful, have humility, etc!).

I think this is a real phenomenon, although I don't think the best point of comparison is the Baumol effect. The Baumol effect is all about the differential impact on different sectors, wheras this would be a kind of universal effect where it's harder to use money to motivate people to work, once they already have a lot of money.

I think a closer point of comparison is simply the high labor costs in rich first-world nations, compared to low labor costs in third-world nations. You can get a haircut or eat a nice meal in India for a tiny fraction of what it costs to buy a similar service in the USA. Partly you could say this is due to a Baumol effect of a sort, where the people in the USA have more productive alternative jobs they could be working, because they're living in a rich country with lots of capital, educated workers, well-run firms, etc. But maybe another part of the equation is that even barbers and cooks in the USA are pretty rich by global standards?

As a person becomes richer, it's perfectly sensible IMO for them to become less willing to do various menial tasks for low pay. But of course there are still some menial tasks that must get done! Imagine a society much richer than ours -- everyone is the equivalent of today's multimillionares (in the sense that they can easily afford lots of high-quality mass-manufactured goods -- they own a big home, plus a few vacation homes, a couple of cars, they can afford to fly all over the world by jet, etc), and many people are the equivalent of billionaires / trillionaires. This society would be awesome, but it would't really be quite as rich as it seems at first glance, because people would still have to perform a bunch of service tasks; we couldn't ALL be retired all the time. I suppose you could just go full-Baumol and pay people exorbitant CEO-wages just to flip burgers at mcdonalds. But in real life society would probably settle on a mix of strategies:

- Making jobs more enjoyable, so people /want/ to do them more, and you don't have to pay them so much to incentivize them. Things like providing a comfortable work environment, trying to have a positive social vibe in the workplace, finding ways to make the work more fun or satisfying than it would normally be (even if this comes at some cost to efficiency).

- Trying to "pay people" in appreciation and (ever-scarce) social status instead of (abundant, ineffective) cash where possible, et cetera. But of course, overall, social-status is somewhat of a zero-sum game, so idk how much juice you could squeeze there...

- Trying to simply minimize the amount of unnecessary service work -- lots more automation wherever it's feasible, even in situations where this creates a slightly downgraded experience for the consumer.

- And then, indeed, just paying people a ton more.

I think strategies like these are already at work when you look at the difference between poor vs rich nations -- jobs in rich countries not only pay more but are also generally more automated, have better working conditions, etc. It's funny to imagine how the future might be WAY further in the rich-world direction than even today's rich world, since it seems so unbalanced to us (just like how paying 30% of GDP for healthcare would've seemed absurd to preindustrial / pre-Baumol-effect societies). But it'll probably happen!

Agreed that the ideas are kind of obvious (from a certain rationalist perspective); nonetheless they are :

1. not widely known outside of rationalist circles, where most people might consider "utopia" to just mean some really mundane thing like "tax billionares enough to provide subsidized medicaid for all" rather than defeating death and achieving other assorted transhumanist treasures

2. potentially EXTREMELY important for the long-term future of civilization

In this regard they seem similar to the idea of existential risk, or the idea that AI might be a really important and pivotal technology -- really really obvious in retrospect, yet underrated in broader societal discourse and potentially extremely important.

Unlike AI & x-risk, I think people who talk about CEV and viatopia have so far done an unimpressive job of exploring how those philosophical ideas about the far-future should be translated into relevant action today. (So many AI safety orgs, billion-dollar companies getting founded, government initiatives launched, lots of useful research and lobbying and etc getting done -- there is no similar game plan for promoting "viatopia" as far as I know!)

"The religious undertones that there is some sort of convergent nirvana once you think hard enough is not true." -- can you argue for this in a convincing and detailed way? If so, that would be exciting -- you would be contributing a very important step towards making concrete progress in thinking about CEV / etc, the exact tractability problem I was just complaining about!! But if you are just asserting a personal vibe without actual evidence or detailed arguments to back it up, then I'd not baldly assert "...is not true".

bostrom uses "existential security" to refer to this intermediate goal state IIRC -- referring to a state where civilization is no longer facing significant risk of extinction or things like stable totalitarianism. this phrase connotes sort of a chill, minimum-viable utopia (just stop people from engineering super-smallpox and everything else stays the same, m'kay?), but I wonder if actual "existential security" might be essentially equivalent to locking in a very specific and as-yet-undiscovered form of governance conducive to suppressing certain dangerous technologies without falling into broader anti-tech stagnation, avoiding various dangers of totalitarianism and fanaticism, etc... https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/NpYjajbCeLmjMRGvZ/human-empowerment-versus-the-longtermist-imperium

yudkowsky might have had a term (perhaps in his fun-theory sequence?) referring to a kind of intermediate utopia where humanity has covered "the basics" of things like existential security plus also some obvious moral goods like individual people no longer die + extreme suffering has been abolished + some basic level of intelligence enhancement for everybody + etc

some people talk about the "long reflection" which is similar to the concept of viatopia, albeit with more of a "pause everything" vibe that seems less practical for a bunch of reasons

it seems like it would be pretty useful for somebody to be thinking ahead about the detailed mechanics of different idealization processes (since maybe such processes do not "converge", and doing things in a slightly different way / slightly different order might send you to very different ultimate destinations: https://joecarlsmith.com/2021/06/21/on-the-limits-of-idealized-values), even though this is probably not super tractable until it becomes clearer what kinds of "idealization technologies" will actually exist when, and what their possible uses will be (brain-computer interfaces, nootropic drugs or genetic enhancement procedures, AI advisors, "Jhourney"-esque spiritual-attainment-assistance technologies, improved collective decisionmaking technologies / institutions, etc)

Okay, yup, that makes sense!

I guess personally:

- I am often dismayed and annoyed by how other people seem to lack particular virtues that I prize, or abilities that I have. Like being not very truthseeking, being interested in stuff that seems dumb and pointless to me, etc.

- But it helps to remember that other people have a lot of virtues that I don't have -- for instance, I'm pretty lazy, but a lot of people I know are incredibly hardworking and diligent even when working miserable, difficult jobs. A lot of people are very empathetic, or have good social awareness, or are good at being pleasant and sociable , which (as I've mentioned) are departments where I'm lacking.

- In particular it helps to remember that many people kind of construct a self-serving moral system that overweights the virtues they themselves possess -- eg, an athelete might tend to think "wow, look at these weaklings who can't even take care of their own health!", while a contrarian nerd will think "I can't believe how much ordinary sheeple go along with convention and don't think for themselves", somebody who appreciates opera and is good at analyzing literature will think "it's criminal how many people go through life consuming whatever entertainment Netflix and Tiktok puts in front of them, without exerting any effort or agency trying to seek out and appreciate the richness that human culture has to offer", and so forth. In my view, taking care of your health, thinking for yourself, and seeking to become cultured are all good virtues! But it's easy to over-index on the virtues you yourself possess and know best, while ignoring the ones that you're weak on. So I try not to judge people too harshly when they fall short in the areas where I'm strongest.

- One way that I notice this self-serving bias is when it shows up around things that are totally unrelated to objective virtues. Like, I notice myself taking pride in the fact that I have good taste in videogames, and I tend to inwardly scoff at how much time other people spend watching prestige-TV shows (I love movies, but generally find the meandering plots of TV shows to be tedious and unsatisfying). But from an external perspective I can recognize that videogames are (in most senses) even more tedious than TV shows, so what the hell am I talking about? Yet I sometimes still have a weird sense of superiority for being the kind of person who knows a lot about The Witness and Kerbal Space Program, instead of the kind of person who knows a lot about Breaking Bad or Game of Thrones or whatever.

- Maybe this is weird/stupid, but to a certain extent, it's almost nice that other people tend to lack some of my virtues, because then I can have something where I can feel special and distinctive. If everyone was really rationalist, I think that would be hugely better for society / the planet overall, but at least on this non-rationalist planet we can have the consolation prize of feeling cool and unique. (Similarly, christians might wish the whole world was christian, but given that it isn't, they can at least take pride in being the few people who manage to keep the faith.)

- In particular I've spent a lot of time lately hanging out with my wife's family, who are pretty dumb and always making stupid decisions on a practical level, misprioritizing things in their life, have bad bland populist politics, are totally uninterested in philosophy except insofar as they're religious and really strongly believe-in-belief, and so on and so on. (I hang out with them so much because they live nearby, help watch our toddler daughter, plus they recently let us live with them for a couple months while we moved out of an apartment but hadn't yet bought a house, etc.)

- My wife and I indeed do look down on them in a lot of ways, and spend a good amount of time complaining about them -- it's hard not to be annoyed by all the various little things they do that we would do differently, since little examples are constantly coming up as we go about our lives, rather than it just being an abstract difference in life philosophies or whatever.

- But again, they have a lot of virtues that help make up for their shortcomings -- most notably they are very family-oriented (for instance they have ben incredibly generous to us re: watching our toddler and letting us live with them for a bit!), do a decent job looking out for each other, et cetera. So, I've gotta respect that in general, and in particular be grateful for the specific helpful things they've done for me.

- They're also sympathetic insofar as their shortcomings are somewhat downstream of challenging life circumstances. They grew up much poorer than I am, in rural Yukon, without even many books around and certainly this was way before rationalist internet communities, etc -- all of this is less conducive to developing a sophisticated worldview, correct takes on epistemology, whatever. Plus they're just 1-2 generations older than me, which makes people less mentally sharp, more set in their ways, etc. So I kinda feel like "there but for the grace of god go I".

- Going further than just ordinary sympathy for overcoming adverse life circumstances, the philosopher Spinoza was the original guy who came up with the "stop believing in free will --> cultivate compassion for your fellow man" concept, and I think there's a lot to recommend that approach. (Some aspects of Buddhism have a similar vibe: at the end of the day, the universe is just a bunch of physics playing out as part of a long chain of dependent origination, so from a certain perspective it seems foolish to get too mad or worked up over it!)

- Finally, although being around them is in some ways aggravating (because it involves regularly watching them make dumb/suboptimal decisions on all different scales), in other ways it's fine and perfectly enjoyable to simply chill out with someone, even if they're dumber than you or whatever. My usual preferred mode of social interaction is, like, intellectual conversation, talking about the news, writing long introspective comments on LessWrong, et cetera, and these approaches don't work well with them. But I can always watch a movie with them, make snacks, have fun playing around with our joyful toddler, go for a walk, talk with them about what I've been up to so far that day and hear what they've been up to, do some joint activity (like doing christmas together or just assembling some ikea furniture or cooking dinner with them), et cetera. It's not the most fun thing ever, but it can be reasonably pleasant.

- I suppose this ability to just chill out is enabled by recognizing that I shouldn't engage with them in my usual most-comfortable / most-preferred way, but should expend a bit of effort making sure to engage with them in a way that works for them. And in a possibly weird/stupid way, it might even be somewhat helpful for me to have a strong sense of my own intellectual superiority in these interactions, similar to how some people (such as in the tumblr SJW space!) talk about people with a "secure sense of masculinity" as opposed to people with an anxious, insecure sense of their masculinity who might be tempted to act really macho and constantly seek social validation of their maleness. My default most-preferred way of interaction can almost be like an intellectual duel or tennis match (or something a little more cooperative than that, but still with competitive aspects): bouncing ideas back and forth, moving fast and making correct intellectual moves, trying to come up with good insights that will be impressive and helpful for the other person. I don't think this is bad, or mostly/entirely motivated by status anxiety or etc. But it's nice to be able to shift out of that "intellectual sparring" mode and interact with people in other ways too. So being able to comfortably think to myself "yeah, this person is not a great intellectual sparring partner" is perhaps useful.

- I think you had this experience in the philosophy meetup and found it horrifying and depressing -- which is very understandable because you literally went to a group that has a giant "THIS CLUB IS FOR DOING TRUTHSEEKING" arrow above the door, and then realized that actually you should switch away from engaging people based on truthseeking to instead just shooting the shit and making jokes!! But in other contexts that don't have a giant "THIS ACTIVITY IS ABOUT TRUTHSEEKING" arrow above the door, I think that a similar technique of "engaging with people on the level that works for them" would seem less horrifying-and-depressing, and more just an application of pragmatism / good social graces / what Buddhists would call skillful means / etc.

- Totally unrelated aside, but I wonder if maybe some of the jokes you were making might have been lampooning some of the contradictions in peoples' thought / making fun of philosophical word-games / generally expressing some of your thinking style and worldview. So although I can see how it felt depressing to shift modes like this, possibly it might not have been as intellectually counterproductive as you're telling it. (More people were converted to rationalism by reading HPMOR than by reading the Sequences, right?) But of course idk, I wasn't there.

- Personally I'd advise against randomly hitting up a sports bar (unless you happen to like sports!), but it could be interesting to pick some random non-intellectual hobby you have (like hiking or videogames or anime or board games or whatever) and meet some folks based on that shared interest.

But hollywood also depicts lasers in this way. Wheras the spherical-white-explosion motif seems uniquely Japanese; you don't see it in western media.