Kudos for getting this interview and posting it! Extremely based.

As for Metz himself, nothing here changed my mind from what I wrote about him three years ago:

But the skill of reporting by itself is utterly insufficient for writing about ideas, to the point where a journalist can forget that ideas are a thing worth writing about. And so Metz stumbled on one of the most prolific generators of ideas on the internet and produced 3,000 words of bland gossip. It’s lame, but it’s not evil.

He just seems not bright or open minded enough to understand different norms of discussion and epistemology than what is in the NYT employee's handbook. It's not dangerous to talk to him (which I did back in 2020, before he pivoted the story to be about Scott). It's just kinda frustrating and pointless.

I feared other women not being into me was a sign she should focus on mating with other guys

When my wife and I just opened up, I did feel jealous quite regularly and eventually realized that the specific thing I was feeling was basically this. It felt like an ego/competitive/status loss thing as opposed to an actual fear of her infidelity or intent to leave me. And then after four years together it went away and never came back.

Now I actually find it kinda fun to not explicitly address "might we fuck?" with some friends, just leave it at the edge of things as a fun wrinkle and a permission to fantasize. A little monogamous frisson, as a treat.

This article made me realize a truth that should've been obvious to me a long time ago: the main benefit I get from polyamory is close female friends (where I don't have to worry about attraction ruining the friendship), sex and romance are secondary.

I spent a long time figuring out the same thing about women's beauty, and came to roughly similar conclusions: https://putanumonit.com/2022/12/13/why-are-women-hot/

We already established that men will happily have sex with women who aren’t optimizing for sexiness, and date women who aren’t the most sexually desirable, and persist in long-term relationships independent of the woman’s looks, and will care about their woman’s beauty in large part to the extent that they care about its effects their status in the hierarchy of men. And so my answer to the original question is:

Women are hot to see themselves, through the internalized standards of society’s judgment, as worthy of their relationships and their happiness.

The honor system sucks ass. Men want to fight for fun or to defend their tribe (I did both!) but not to be compelled into a fight by any random moron insulting them or they'll face social repercussions from within their own people.

Countercounterpoint: I just wanted to fight in rationalist fight club and it was great fun, I don't really care about winning (and not much about training).

By "everything is just experiences" I mean that all I have of the rock are experiences: its color, its apparent physical realness, etc. As for the rock itself, I highly doubt that it experiences anything.

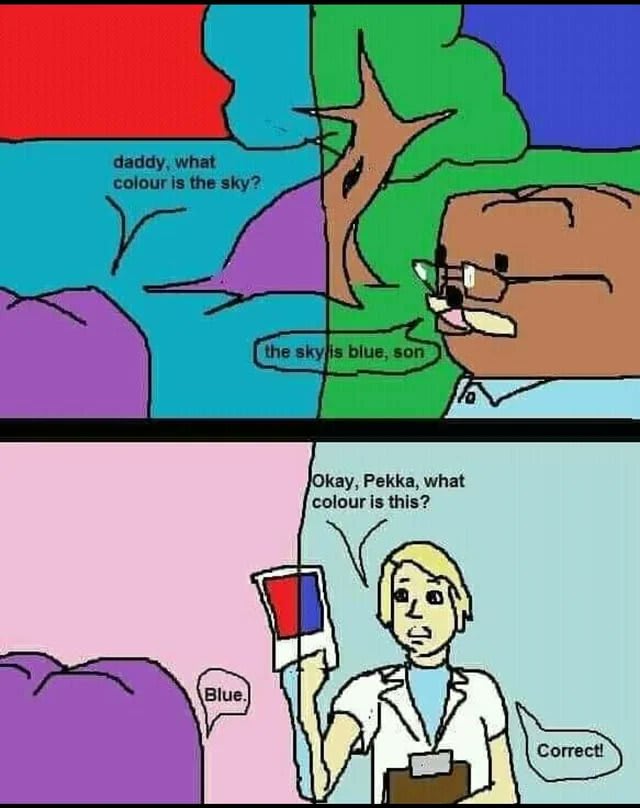

As for your red being my red, we can compare the real phenomenology of it: does your red feel closer to purple or orange? Does it make you hungry or horny? But there's no intersubjective realm in which the qualia themselves of my red and your red can be compared, and no causal effect of the qualia themselves that can be measured or even discussed.

I feel that understanding that "is your red the same as my red" is a question-like sentence that doesn't actually point to any meaningful question is equivalent to understanding that HPoC is a confusion, and it's perhaps easier to start with this.

Here's a koan: WHO is seeing two "different" blues in the picture below?

I tried to communicate a psychological process that occurred for me: I used to feel that there's something to the Hard Problem of Consciousness, then I read this book explaining the qualities of our phenomenology, now I don't think there's anything to HPoC. This isn't really ignoring HPoC, it's offering a way out that seems more productive than addressing it directly. This is in part because terms HPoC insists on for addressing it are themselves confused and ambiguous.

With that said, let me try to actually address HPoC directly although I suspect that this will not be much more convincing.

HPoC roughly asks "why is perceiving redness accompanies by the quale of redness". This can be interpreted in one of two ways.

1. Why this quale and not another?

This isn't a meaningful question because the only thing that determines a quale as being a "quale of redness" is that it accompanies a perception of something red. I suspect that when people read these words they imagine something like looking at a tomato and seeing blue, but that's incoherent — you can't perceive red but have a "blue" quale.

2. Why this quale and not nothing?

Here it's useful to separate the perception of redness, i.e. a red object being part of the map, and the awareness of perceiving redness, i.e. a self that perceives a red object being part of the map. These are two separate perceptions. I suspect that when people think about p-zombies or whatever they imagine experiencing nothingness or oblivion, and not a perception unaccompanied by experience, or they imagine some subliminal "red" making them hungry similar to how it would affect a p-zombie. There is no coherent way to imagine being aware of perceiving red, and this being different from just perceiving red, without this awareness being an experience. All you have is experience.

HPoC is demanding a justification of experience from within a world in which everything is just experiences. Of course it can't be answered! If it could formulate a different world that was even in principle conceivable, it would make sense to ask why we're in world A and not in world B. But this second world isn't really conceivable if you focus on what it would mean. The things you're actually imagining are seeing a blue tomato or seeing nothing or seeing a tomato without being aware of it, you're not actually imagining an awareness of seeing a red tomato that isn't accompanied by experience.

I understand where you're coming from, but I think that norms about e.g. warning people about writing from an objectionable frame only makes sense for personal blogs and it's not a very reasonable expectation for a forum like LessWrong. These things are always very subjective (the three women I sent this post to for review certainly didn't feel that it assumed a male audience!). While a single author can create a shared expectation of what they mean by e.g. "warning: sexualizing" with their readers I don't think a whole community can or should try to formalize this as a norm.

Which means that it's on the reader to look out for themselves. I'm not going to put content warnings on my writing, but if you decide based on this post that you will not read anything written by me that's tagged "sex and gender" that's fair.

You're making a great point: an important function of the female approach is to filter out guys who think most women are "completely fucking idiotic".