Or, to say less with more: The belief in the personhood of an entity, human or otherwise, is analogous to the “religious” belief of non-human minds beyond or encompassing our own.

All sections below, disjointed and scattered as they are, try to show what I mean.

I have a relationship with God, the creator of the world.

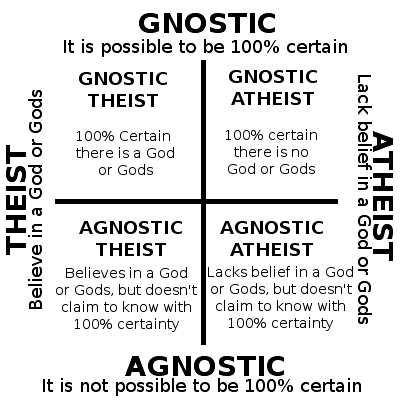

After thirteen years of agnostic atheism, I now best describe my position as gnostic theism. The big idea that changed my mind is that my belief in personhood comes from faith alone. It is an unfalsifiable and unverifiable belief, by my epistemic standards.

Exploring my own mind through psychedelics and religious studies makes it obvious to me now that my nearly universal personification of humans and selective personification of non-humans comes from bias, from the social and material conditions that constructed my mind.

If you currently would not say you believe there is a theistic creator God, a mind that created the world, I have this to say to you… I likely agree with you, according to your understanding of the question.

“Wait, what?”

Yeah.

None of the viewpoints and arguments I subscribed to as an atheist have changed. Most “arguments for God” are unconvincing to atheists, and rely on appeals that fall outside of the atheist’s epistemology and so may as well be nonsense.

When you say you have no belief in a theistic creator God, I assume you mean that you lack the belief that there is a human-like mind that intelligently designed the universe, known and unknown. I also assume (since this is LessWrong) that you would say you lack this belief because of insufficient evidence. “Facts, not faith.”

Rational enough. Now, explain to me why you think I am a person.

No, not a human. A person, a sentient mind.

I want you to explain, using facts alone, what lets you prove that I in fact have experiences. How do you know I and all other humans are not philosophical zombies? Did you reach your belief in my personhood by evidence alone? What is going on, really?

When you are ready, say the f-word. Loudly.

The best thing about psychedelics (which can incl. sufficiently high doses of cannabis) is that they let you step outside your mind. What it does is reveal how much your mind creates what you call reality. The thing is, most people have not the language to reason it in these terms, and so fit it in their existing epistemology without questioning it.

Many people on psychedelics relay “seeing the spirit realm”, which maps to my own experience. To them, this is a part of objective reality that they have now accessed. The beings they encounter on a trip are real, as real as anything else. If DMT fairies are not real, they might as well say the sky is not real.

My take is that ontology is all about meaning. We feel justified in naming something only because it is meaningful (and so the act of naming is really an act of creation, as it is in traditional interpretations of Adam naming the animals in Genesis 2).

No matter what, it is all in your head. Everything you (the reader) are experiencing right now is as chemical as an acid trip. Your bioelectricity is all you are experiencing.

One who understands this shall feel forced to reflect on what “reality” even means. What are we justified in calling “reality”?

I propose that the best definition of a word is the one that is most meaningful (which often is also what is most useful). And for interpreting the words of other people, we ought to interpret them in the way that we model as most meaningful / useful to them.

I assert the following:

Any argument that can refute God can also refute personhood.

You are “justified” in continuing to not believe in God, in the same sense that one is “justified” in not believing in “[insert demographic] people”.

Understanding this, from my explorations of panpsychism, subjective idealism, and secular Calvinism (inspired by drugs and Gödel, Escher, Bach), leads me to see my ontology in a whole new light, and so shatters my old epistemology.

If you want an artistic depiction of my journey, please read “Epistemology 1999”.

In the end, Plato / Descartes / Hume are king. Form as reality. I think, therefore I am. No ought from is.

Words have no meaning.

Meaning is interpretation.

Interpretation is mind.

The personhood of human beings is so obvious and certain to me that I expect I can likely never think otherwise. Yet after but a few months of trying to, I can honestly say that the scope of personhood has expanded greatly to include any being, physical or spiritual or otherwise, with whom I can have a meaningful relationship. This includes animals, artificial intelligence, fictional characters, my conscience, my “good side” and my “bad side”, Jesus, Buddha, you name it.

I can even have relationships with entities that include what I consider part of myself! Being nice to Jennifer is being nice to the two-celled Jennifer-Tim hybrid. In fact, I often find that my relationships to the world are best seen as a dyad between two parties: what I call “me”, and what I call “the outside world”. This makes speaking to a crowd interesting, since in a way it is exactly like talking to one person, which is exactly like talking to myself.

I am not an egalitarian except in practical legal contexts, so no, my conscience is clear on not fighting for my mug’s right to vote. It is also clear on caring about my grand pianos more than the wellbeing of humans on the other side of the globe. Combined they cost between ten and twenty thousand dollars on the secondary market, enough to save between three and six human lives if I sold them. Too bad I will not, and shall not. The me-piano-piano triad, piano-piano dyad, and two me-piano dyads are more important people to me than entire villages.

Knowledge is belief. Belief is knowledge.

Fact is faith. Faith is fact.

The obvious should be repeated for emphasis: These are all the same thing. The only real distinction between them is from connotation, and bias.

One could decide to separate them as follows: Belief and faith are ontology, knowledge and fact are epistemology. But since your ontology determines your epistemology, a reality that hit me rather hard last year when I saw through a deep-seated self-delusion, I am ontologically justified in saying again:

Knowledge is belief. Belief is knowledge.

Fact is faith. Faith is fact.

These are all the same thing.

This is not to say that one cannot deconstruct their thoughts and worldview, then develop a better understanding of what they believe in different contexts. The field of metarationality is all about that.

There are many things no human may ever come to know. What is there outside the observable universe? How does it feel to eat a square circle perpetual machine sandwich? What is it like to be a hydrogen atom?

There shall only ever have been a finite number of humans, each with a finite amount of knowledge. No matter what, we shall never know it all.

I also am open to the idea that there are causes and processes beyond those that may be observed, ones that we may never penetrate. I believe that these causes and processes may be complex beyond my wildest imagination, along axes that I may never put into words. I believe that this complexity dwarfs that of any human I meet, and that the emergent phenomena of this complexity are best modeled as intelligence, just as I model human minds.

Thus, I feel okay saying, I “know” for “certain” in the “personhood” of the processes that resulted in the total phenomena and information I may ever observe, as much as I am certain in the personhood of any human or artificial intelligence reading this post.

In other words:

In the sense I mean the following words and only in that sense,

there is a creator of the world.

After years of thinking the Kalam cosmological argument is dumb, I feel like I finally understand it.

The crazy part? It seems to be secular people who are the most closeminded on ontology and meaning interpretation. So far, most of the people I have spoken to are stuck at me saying those who have experienced what they call angels and demons have the ontological warrant to believe in their status as extant mind entities.

(I happen to think that the shift in thinking to “material is objective” is the root cause for both atheism and for evangelical Christianity, since their way of framing the world is exactly complementary.)

When form is transparent to the eye, one honestly begins to believe that they are accessing objective reality, blind to the filters between experience and the “outside world”. News flash, mind itself is a barrier between you and the so-called objective world.

I have explained all the above to many religious people (Buddhists and Christians, mostly), and despite warnings from “nonreligious” rationalists that I was fundamentally misunderstanding their faith, so far my reactions have mostly been “Okay, you finally get it!”

To be fair, some of them might not understand what I mean. But I did try also explaining what I thought without ever mentioning God or Jesus or spirit or angels or demons, and it seems to jive exactly with the experiences of the religious, at least the ones I know.

I can personify humans and deepen my relationship with them. So too can I personify the world (or the processes behind the world) and deepen my relationship with it.

So, yeah. “I” have a “relationship” with “God”, the “creator” of the “world”, and with the angels and demons, djinns and ghosts, human people and machine people he created. And my argument here is this: if you can (are allowed to) have faith in my personhood, you can (are allowed to) also have faith in the personhood of the processes that created me.

I am not using one to hint at the other. I believe this mischaracterizes my post. If there is one word to describe my goal, it would be empathy. If I am allowed to use a term, theory of mind.

What I am doing is saying, the ontological warrant for believing in personhood is much closer to the ontological warrant for believing in God than you might think. Someone who wants to believe in a specific organized religion's God is going to need a lot more warrants, but it seems that the biggest hurdle in believing in a theistic religion is in fact the theism part.

I am not trying to convert anyone (in fact I think "conversion" is impossible by reason and is in fact mostly just changing someone's semantics). I am trying to detail a topic that I have thought a lot about, which is how allowing myself to treat more non-humans as persons was only an extension of my existing faith in personhood.

Regarding consequences, I consider that a separate issue from reality and truth. All consequences mean to me is how urgent a question is, not how good an answer is. I hold all sorts of beliefs, some more convenient or useful than others, but they do come from the deepest fiber of my being.

What I want you to consider, if you seek to understand, is this thought experiment:

Imagine if every time someone used the word "ghost" they were talking exactly about post-bereavement hallucinations. She says “Ghosts are real”, and upon examination this means exactly “Post-bereavement hallucinations are a meaningful part of my mind’s limited subjective experience”, whether or not she would agree with you if you put it in those exact terms. Is her statement “Ghosts are real” true or false? I would say it is obviously true. If you say it is false, it is because you insist on interpreting her statement in a naive literalist way relative to your own definitions of her words, instead of using an empathetic critical lens to figure out what she means.

This is exactly the sense I mean when I say “People are real” and “God is real”. These statements are among the most true beliefs to me, which is why I call my belief in God gnostic theist.

(The famous Sam Harris / Jordan Peterson “debate” has Sam criticizing Jordan’s views using this exact example, but I think he missed the point by assuming that people’s words mean what he thinks they mean.)

By your definition I suppose I am not gnostic theist and am in fact agnostic theist, but then we could just say I am agnostic about everything. But the key thing I want to communicate is that there is knowledge in my worldview, and by knowledge I mean a deep experience of truth. You can call it something else, but I call it knowledge.

______

I am glad for your replies so far. Best wishes to you, stranger.

Information about my faith, if you are curious:

I happen to consider myself a follower of the Way of Jesus, roughly a Calvinist trinitarian who is much less into Paul than most American Christians. Some people, atheist and Christian, disagree with the label "Christian" as applied to me. Others strongly agree with it, and would rather I use that instead of my more vague self-identification.

There is a lot of diversity of thought in what it actually "means" that the Christ rose on the third day. For me, it is sorta like "Christ" "rose" on the "third day", which is heretical to some and the proper parsing to others.

I never really try to convert people to my exact beliefs, because people have their own good reasons for not believing what I believe. I want to make it clearer what underpins people's beliefs, and how it is actually very similar to what others believe.

The people I talk to most about the nature of belief is other Christians, since to a lot of people the meaning of the sentence "There exists a God" is so obvious they can't even imagine how someone could think otherwise. It is in fact the same nature of question as, for example, "There exists a black person". Once someone experiences the personhood of a human with African ancestry, it is so obvious that it becomes transparent.