These quotes from When ChatGPT Broke an Entire Field: An Oral History stood out to me:

...On November 30, 2022, OpenAI launched its experimental chatbot. ChatGPT hit the NLP community like an asteroid.

IZ BELTAGY (lead research scientist, Allen Institute for AI; chief scientist and co-founder, SpiffyAI): In a day, a lot of the problems that a large percentage of researchers were working on — they just disappeared. ...

R. THOMAS MCCOY: It’s reasonably common for a specific research project to get scooped or be eliminated by someone else’s similar thing. But ChatGPT did that to entire types of research, not just specific projects. A lot of higher categories of NLP just became no longer interesting — or no longer practical — for academics to do. ...

IZ BELTAGY: I sensed that dread and confusion during EMNLP [Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing], which is one of the leading conferences. It happened in December, a week after the release of ChatGPT. Everybody was still shocked: “Is this going to be the last NLP conference?” This is actually a literal phrase that someone said. During lunches and cocktails and conversations in the halls, everybody was asking the same q

Wow. I knew academics were behind / out of the loop / etc. but this surprised me. I imagine these researchers had at least heard about GPT2 and GPT3 and the scaling laws papers; I wonder what they thought of them at the time. I wonder what they think now about what they thought at the time.

The full article sort of explains the bizarre kafkaesque academic dance that went on from 2020-2022, and how the field talked about these changes.

ChatGPT was "so good they can't ignore you"; the Hugging Face anecdote is particularly telling. At some point, everyone else gets tired of waiting for your cargo to land, and will fire you if you don't get with the program. "You say semantics can never be learned from syntax and you've proven that ChatGPT can never be useful? It seems plenty useful to me and everyone else. Figure it out or we'll find someone who can."

I don't think there's any necessary contradiction. Verification or prediction of what? More data. What data? Data. You seem to think there's some sort of special reality-fluid which JPEGs or MP3s have but .txt files do not, but they don't; they all share the Buddha-nature.

Consider Bender's octopus example, where she says that it can't learn to do anything from watching messages go back and forth. This is obviously false, because we do this all the time; for example, you can teach a LLM to play good chess simply by watching a lot of moves fly by back and forth as people play postal chess. Imitation learning & offline RL are important use-cases of RL and no one would claim it doesn't work or is impossible in principle.

Can you make predictions and statements which can be verified by watching postal chess games? Of course. Just predict what the next move will be. "I think he will castle, instead of moving the knight." [later] "Oh no, I was wrong! I anticipated seeing a castling move, and I did not, I saw something else. My beliefs about castling did not pay rent and were not verified by subsequent observations of this game. I will update my priors and do better next time."

Well, in the chess example we do not have any obvious map/territory relation.

Yes, there is. The transcripts are of 10 million games that real humans played to cover the distribution of real games, and then were annotated by Stockfish, to provide superhuman-quality metadata on good vs bad moves. That is the territory. The map is the set of transcripts.

But if you can understand text from form alone, as LLMs seem to prove, the message simply has to be long enough.

I would say 'diverse enough', not 'long enough'. (An encyclopedia will teach a LLM many things; a dictionary the same length, probably not.) Similar to meta-learning vs learning.

the pieces do not seem to refer to anything in the external world.

What external world does our 'external world' itself refer to things inside of? If the 'external world' doesn't need its own external world for grounding, then why does lots of text about the external world not suffice? (And if it does, what grounds that external external world, or where does the regress end?) As I like to put it, for an LLM, 'reality' is just the largest fictional setting - the one that encompasses all the other fictional settings it reads about from time to time.

As someone who doubtless does quite a lot of reading about things or writing to people you have never seen nor met in real life and have no 'sensory' way of knowing that they exist, this is a position you should find sympathetic.

Interesting anecdote on "von Neumann's onion" and his general style, from P. R. Halmos' The Legend of John von Neumann:

...Style. As a writer of mathematics von Neumann was clear, but not clean; he was powerful but not elegant. He seemed to love fussy detail, needless repetition, and notation so explicit as to be confusing. To maintain a logically valid but perfectly transparent and unimportant distinction, in one paper he introduced an extension of the usual functional notation: along with the standard φ(x) he dealt also with something denoted by φ((x)). The hair that was split to get there had to be split again a little later, and there was φ(((x))), and, ultimately, φ((((x)))). Equations such as

(φ((((a))))^2 = φ(((a))))

have to be peeled before they can be digested; some irreverent students referred to this paper as von Neumann’s onion.

Perhaps one reason for von Neumann’s attention to detail was that he found it quicker to hack through the underbrush himself than to trace references and see what others had done. The result was that sometimes he appeared ignorant of the standard literature. If he needed facts, well-known facts, from Lebesgue integration theory, he waded in, defi

I have this experience with @ryan_greenblatt -- he's got an incredible ability to keep really large and complicated argument trees in his head, so he feels much less need to come up with slightly-lossy abstractions and categorizations than e.g. I do. This is part of why his work often feels like huge, mostly unstructured lists. (The lists are more unstructured before his pre-release commenters beg him to structure them more.) (His code often also looks confusing to me, for similar reasons.)

While Dyson's birds and frogs archetypes of mathematicians is oft-mentioned, David Mumford's tribes of mathematicians is underappreciated, and I find myself pointing to it often in discussions that devolve into "my preferred kind of math research is better than yours"-type aesthetic arguments:

...... the subjective nature and attendant excitement during mathematical activity, including a sense of its beauty, varies greatly from mathematician to mathematician... I think one can make a case for dividing mathematicians into several tribes depending on what most strongly drives them into their esoteric world. I like to call these tribes explorers, alchemists, wrestlers and detectives. Of course, many mathematicians move between tribes and some results are not cleanly part the property of one tribe.

- Explorers are people who ask -- are there objects with such and such properties and if so, how many? They feel they are discovering what lies in some distant mathematical continent and, by dint of pure thought, shining a light and reporting back what lies out there. The most beautiful things for them are the wholly new objects that they discover (the phrase 'bright shiny objects' has been i

Scott Alexander's Mistakes, Dan Luu's Major errors on this blog (and their corrections), Gwern's My Mistakes (last updated 11 years ago), and Nintil's Mistakes (h/t @Rasool) are the only online writers I know of who maintain a dedicated, centralized page solely for cataloging their errors, which I admire. Probably not coincidentally they're also among the thinkers I respect the most for repeatedly empirically grounding their reasoning. Some orgs do this too, like 80K's Our mistakes, CEA's Mistakes we've made, and GiveWell's Our mistakes.

While I prefer dedicated centralized pages like those to one-off writeups for long content benefit reasons, one-off definitely beats none (myself included). In that regard I appreciate essays like Holden Karnofsky's Some Key Ways in Which I've Changed My Mind Over the Last Several Years (2016), Denise Melchin's My mistakes on the path to impact (2020), Zach Groff's Things I've Changed My Mind on This Year (2017), Michael Dickens' things I've changed my mind on, and this 2013 LW repository for "major, life-altering mistakes that you or others have made", as well as by orgs like HLI's Learning from our mistakes.

In this vein I'm also sad to see m...

I really liked this extended passage on math circles from John Psmith's REVIEW: Math from Three to Seven, by Alexander Zvonkin, it made me wish math circles existed in my home country when I was younger:

...in the interviews I’ve read with Soviet mathematicians and scientists, the things that come up over and over again are “mathematical circles,” a practice that originated in the pre-revolutionary Russian Empire and then spread far and wide through the Soviet Union. A mathematical circle is an informal group of teenagers and adults who really enjoy math and want to spend a lot of time thinking and talking about it. They’re a little bit like sports teams, in that they develop their own high-intensity internal culture and camaraderie, and often have a “coach” who is especially talented or famous. But they’re also very unlike sports teams, because they don’t compete with each other or play in leagues or anything like that, and usually any given circle will contain members of widely varying skill levels. Maybe a better analogy is a neighborhood musical ensemble that gets together and jams on a regular basis, but for math.

The most important thing to understand about mathematical circles is

Peter Watts is working with Neill Blomkamp to adapt his novel Blindsight into an 8-10-episode series:

...“I can at least say the project exists, now: I’m about to start writing an episodic treatment for an 8-10-episode series adaptation of my novel Blindsight.

“Neill and I have had a long and tortured history with that property. When he first expressed interest, the rights were tied up with a third party. We almost made it work regardless; Neill was initially interested in doing a movie that wasn’t set in the Blindsight universe at all, but which merely used the speculative biology I’d invented to justify the existence of Blindsight’s vampires. “Sicario with Vampires” was Neill’s elevator pitch, and as chance would have it the guys who had the rights back then had forgotten to renew them. So we just hunkered quietly until those rights expired, and the recently-rights-holding parties said Oh my goodness we thought we’d renewed those already can we have them back? And I said, Sure; but you gotta carve out this little IP exclusion on the biology so Neill can do his vampire thing.

“It seemed like a good idea at the time. It was good idea, dammit. We got the carve-out and everything. Bu

Blindsight was very well written but based on a premise that I think is importantly and dangerously wrong. That premise is that consciousness (in the sense of cognitive self-awareness) is not important for complex cognition.

This is the opposite of true, and a failure to recognize this is why people are predicting fantastic tool AI that doesn't become self-aware and goal-directed.

The proof won't fit in the margin unfortunately. To just gesture in that direction: it is possible to do complex general cognition without being able to think about one's self and one's cognition. It is much easier to do complex general cognition if the system is able to think about itself and its own thoughts.

What fraction of economically-valuable cognitive labor is already being automated today? How has that changed over time, especially recently?

I notice I'm confused about these ostensibly extremely basic questions, which arose in reading Open Phil's old CCF-takeoff report, whose main metric is "time from AI that could readily[2] automate 20% of cognitive tasks to AI that could readily automate 100% of cognitive tasks". A cursory search of Epoch's data, Metaculus, and this forum didn't turn up anything, but I didn't spend much time at all doing so.

I was originally motivated by wanting to empirically understand recursive AI self-improvement better, which led to me stumbling upon the CAIS paper Examples of AI Improving AI, but I don't have any sense whatsoever of how the paper's 39 examples as of Oct-2023 translate to OP's main metric even after constraining "cognitive tasks" in its operational definition to just AI R&D.

I did find this 2018 survey of expert opinion

...A survey was administered to attendees of three AI conferences during the summer of 2018 (ICML, IJCAI and the HLAI conference). The survey included questions for estimating AI capabilities over the next d

I chose to study physics in undergrad because I wanted to "understand the universe" and naively thought string theory was the logically correct endpoint of this pursuit, and was only saved from that fate by not being smart enough to get into a good grad school. Since then I've come to conclude that string theory is probably a dead end, albeit an astonishingly alluring one for a particular type of person. In that regard I find anecdotes like the following by Ron Maimon on Physics SE interesting — the reason string theorists believe isn’t the same as what they tell people, so it’s better to ask for their conversion stories:

...I think that it is better to ask for a compelling argument that the physics of gravity requires a string theory completion, rather than a mathematical proof, which would be full of implicit assumptions anyway. The arguments people give in the literature are not the same as the personal reasons that they believe the theory, they are usually just stories made up to sound persuasive to students or to the general public. They fall apart under scrutiny. The real reasons take the form of a conversion story, and are much more subjective, and much less persuasive to everyo

In pure math, mathematicians seek "morality", which sounds similar to Ron's string theory conversion stories above. Eugenia Cheng's Mathematics, morally argues:

...I claim that although proof is what supposedly establishes the undeniable truth of a piece of mathematics, proof doesn’t actually convince mathematicians of that truth. And something else does.

... formal mathematical proofs may be wonderfully watertight, but they are impossible to understand. Which is why we don’t write whole formal mathematical proofs. ... Actually, when we write proofs what we have to do is convince the community that it could be turned into a formal proof. It is a highly sociological process, like appearing before a jury of twelve good men-and-true. The court, ultimately, cannot actually know if the accused actually ‘did it’ but that’s not the point; the point is to convince the jury. Like verdicts in court, our ‘sociological proofs’ can turn out to be wrong—errors are regularly found in published proofs that have been generally accepted as true. So much for mathematical proof being the source of our certainty. Mathematical proof in practice is certainly fallible.

But this isn’t the only

I used to consider it a mystery that math was so unreasonably effective in the natural sciences, but changed my mind after reading this essay by Eric S. Raymond (who's here on the forum, hi and thanks Eric), in particular this part, which is as good a question dissolution as any I've seen:

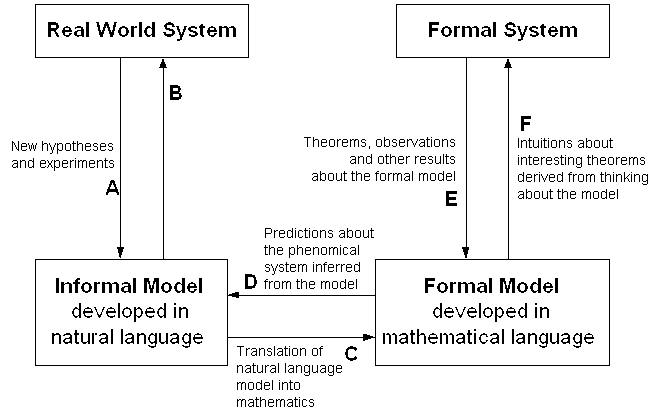

The relationship between mathematical models and phenomenal prediction is complicated, not just in practice but in principle. Much more complicated because, as we now know, there are mutually exclusive ways to axiomatize mathematics! It can be diagrammed as follows (thanks to Jesse Perry for supplying the original of this chart):

(it's a shame this chart isn't rendering properly for some reason, since without it the rest of Eric's quote is ~incomprehensible)

...The key transactions for our purposes are C and D -- the translations between a predictive model and a mathematical formalism. What mystified Einstein is how often D leads to new insights.

We begin to get some handle on the problem if we phrase it more precisely; that is, "Why does a good choice of C so often yield new knowledge via D?"

The simplest answer is to invert the question and treat it as a definition. A "good choi

This remark at 16:10 by Dwarkesh Patel on his most recent podcast interview AMA: Career Advice Given AGI, How I Research ft. Sholto & Trenton was pretty funny:

... big guests just don't really matter that much if you just look at what are the most popular episodes, or what in the long run helps a podcast grow. By far my most popular guest is Sarah Paine, and she, before I interviewed her, was just a scholar who was not publicly well-known at all, and I just found her books quite interesting—so my most popular guests are Sarah Paine and then Sarah Paine, Sarah Paine, Sarah Paine because I have

electric chairs(?)a lecture series with her. And by the way, from a viewer-a-minute adjusted basis, I host the Sarah Paine podcast where I occasionally talk about AI.

(After Sarah Paine comes geneticist David Reich, then Satya Nadella and Mark Zuckerberg, "then [Sholto & Trenton] or Leopold (Aschenbrenner) or something, then you get to the lab CEOs or something")

You can see it as an example of 'alpha' vs 'beta'. When someone asks me about the value of someone as a guest, I tend to ask: "do they have anything new to say? didn't they just do a big interview last year?" and if they don't but they're big, "can you ask them good questions that get them out of their 'book'?" Big guests are not necessarily as valuable as they may seem because they are highly-exposed, which means both that (1) they have probably said everything they will said before and there is no 'news' or novelty, and (2) they are message-disciplined and careful to "talk their book". (In this analogy, "alpha" represents undiscovered or neglected interview topics which can be extracted mostly just by finding it and then asking the obvious question, usually by interviewing new people; "beta" represents doing standard interview topics/people, but much more so - harder, faster, better - and getting new stuff that way.)

Lex Fridman podcasts are an example of this: he often hosts very big guests like Mark Zuckerberg, but nevertheless, I will sit down and skim through the transcript of 2-4 hours of content, and find nothing even worth excerpting for my notes. Fridman notoriously does n...

Balioc's A taxonomy of bullshit jobs has a category called Worthy Work Made Bullshit which resonated with me most of all:

...Worthy Work Made Bullshit is perhaps the trickiest and most controversial category, but as far as I’m concerned it’s one of the most important. This is meant to cover jobs where you’re doing something that is obviously and directly worthwhile…at least in theory…but the structure of the job, and the institutional demands that are imposed on you, turn your work into bullshit.

The conceptual archetype here is the Soviet tire factory that produces millions of tiny useless toy-sized tires instead of a somewhat-smaller number of actually-valuable tires that could be put on actual vehicles, because the quota scheme is badly designed. Everyone in that factory has a Worthy Work Made Bullshit job. Making tires is something you can be proud of, at least hypothetically. Making tiny useless tires to game a quota system is…not.

Nowadays we don’t have Soviet central planners producing insane demands, but we do have a marketplace that produces comparably-insane demands, especially in certain fields.

This is especially poignant, and e

Unbundling Tools for Thought is an essay by Fernando Borretti I found via Gwern's comment which immediately resonated with me (emphasis mine):

...I’ve written something like six or seven personal wikis over the past decade. It’s actually an incredibly advanced form of procrastination1. At this point I’ve tried every possible design choice.

Lifecycle: I’ve built a few compiler-style wikis: plain-text files in a

gitrepo statically compiled to HTML. I’ve built a couple using live servers with server-side rendering. The latest one is an API server with a React frontend.Storage: I started with plain text files in a git repo, then moved to an SQLite database with a simple schema. The latest version is an avant-garde object-oriented hypermedia database with bidirectional links implemented on top of SQLite.

Markup: I used Markdown here and there. Then I built my own TeX-inspired markup language. Then I tried XML, with mixed results. The latest version uses a WYSIWYG editor made with ProseMirror.

And yet I don’t use them. Why? Building them was fun, sure, but there must be utility to a personal database.

At first I thought the problem was friction: the higher the activation energy to u

Venkatesh Rao surprised me in What makes a good teacher? by saying the opposite of what I expected him to say re: his educational experience, given who he is:

...While my current studies have no live teachers in the loop, each time I sit down to study something seriously, I’m reminded of how much I’m practicing behaviors first learned under the watchful eye of good teachers. We tend to remember the exceptionally charismatic (which is not the same thing as good), and exceptionally terrible teachers, but much of what we know about how to learn, how to study, comes from the quieter good teachers, many of whom we forget.

It also strikes me, reflecting on my own educational path — very conventional both on paper and in reality — that the modern public discourse around teaching and learning has been hijacked to a remarkable degree by charismatic public figures mythologizing their own supposedly maverick education stories.

These stories often feature exaggerated elements of rebellion, autodidact mastery, subversive hacking, heroic confrontations with villainous teachers and schoolyard bullies, genius non-neurotypical personal innovations and breakthroughs, and powerful experiences outside forma

(Not a take, just pulling out infographics and quotes for future reference from the new DeepMind paper outlining their approach to technical AGI safety and security)

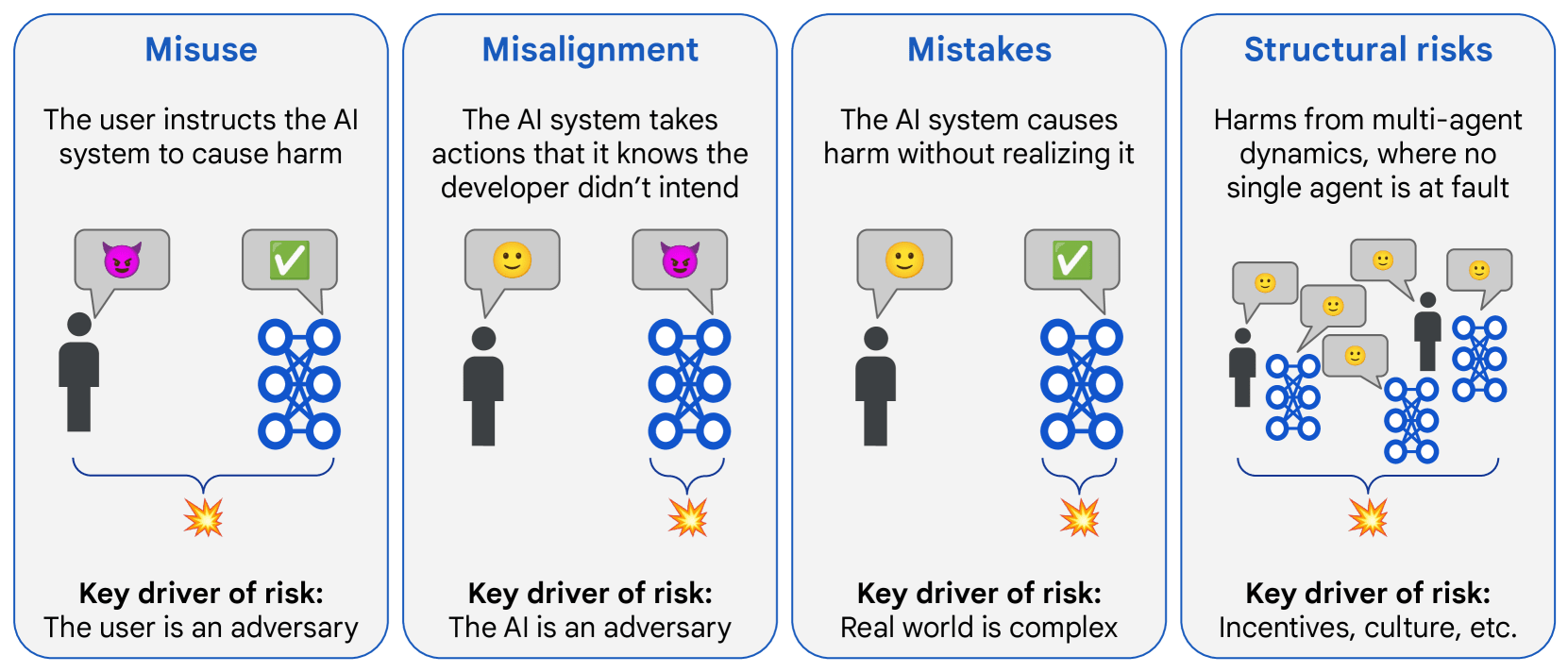

Overview of risk areas, grouped by factors that drive differences in mitigation approaches:

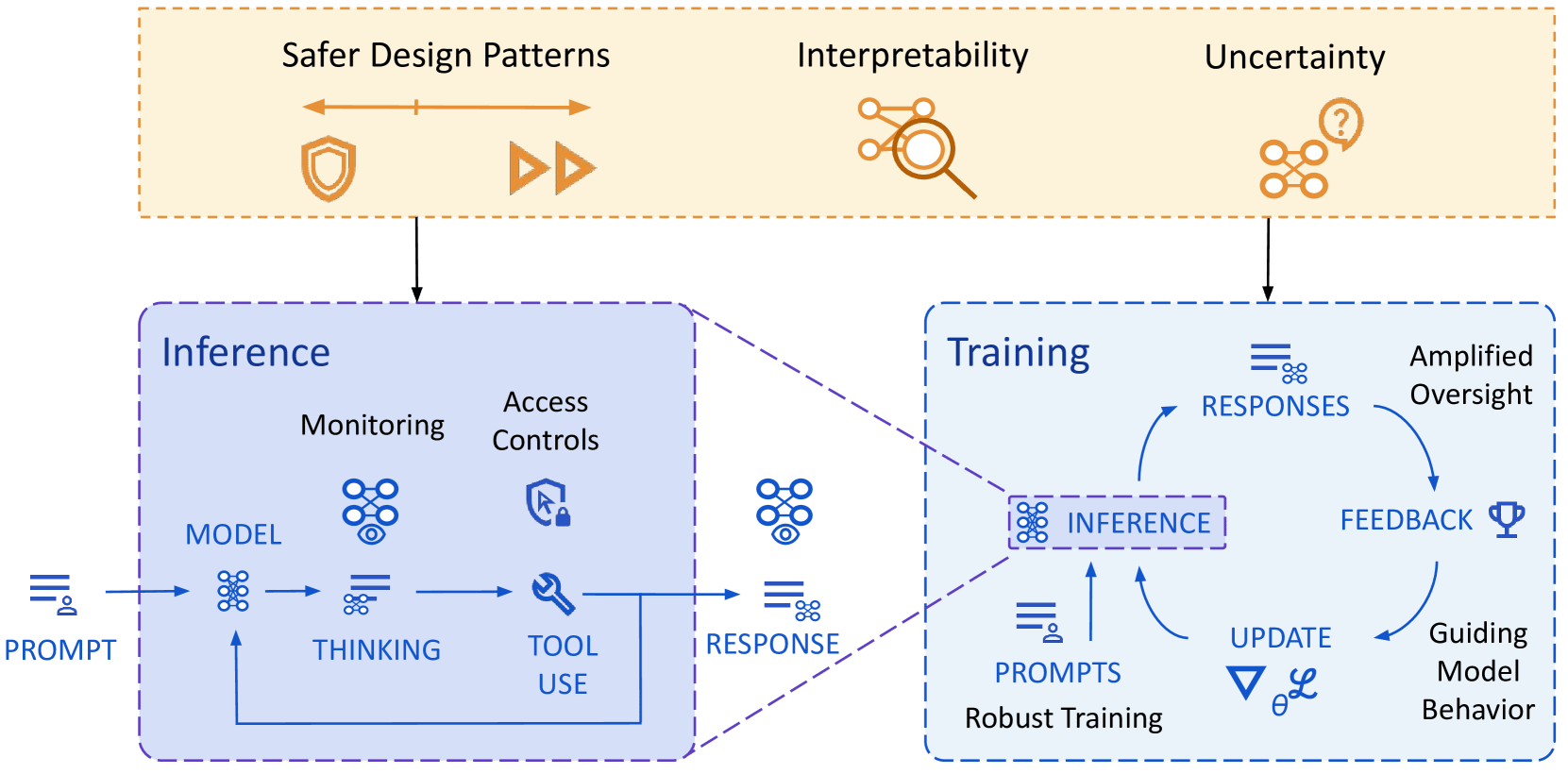

Overview of their approach to mitigating misalignment:

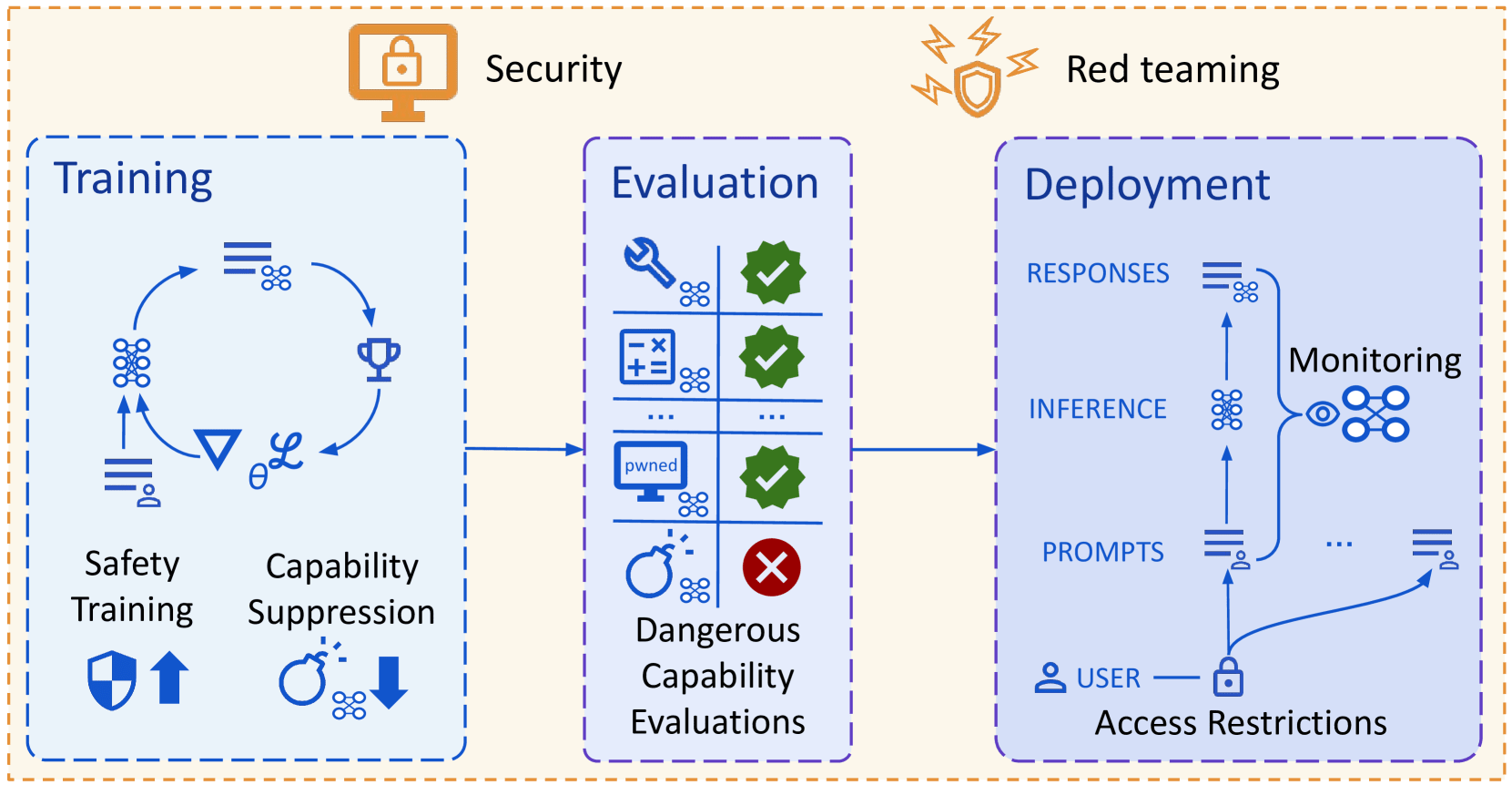

Overview of their approach to mitigating misuse:

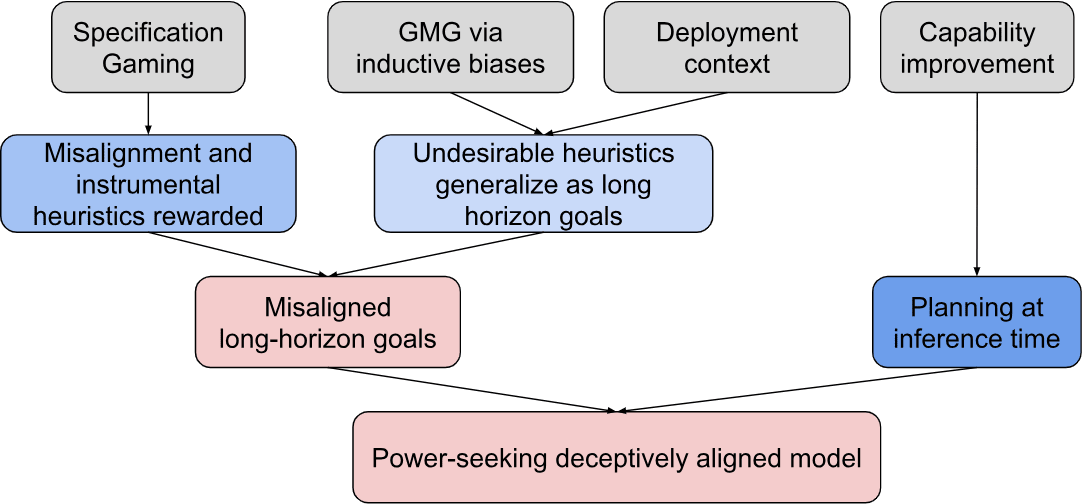

Path to deceptive alignment:

How to use interpretability:

| Goal | Understanding v Control | Confidence | Concept v Algorithm | (Un)supervised? | How context specific? |

| Alignment evaluations | Understanding | Any | Concept+ | Either | Either |

| FaithfulReasoning | Understanding∗ | Any | Concept+ | Supervised+ | Either |

| DebuggingFailures | Understanding∗ | Low | Either | Unsupervised+ | Specific |

| Monitoring | Understanding | Any | Concept+ | Supervised+ | General |

| Red teaming | Either | Low | Either | Unsupervised+ | Specific |

| Amplified oversight | Understanding | Complicated | Concept | Either | Specific |

Interpretability techniques:

| Technique | Understanding v Control | Confidence | Concept v Algorithm | (Un)supervised? | How specific? | Scalability |

| Probing | Understanding | Low | Concept | Supervised | Specific-ish | Cheap |

| Dictionary learning | Both | Low | Concept | Unsupervised | General∗ | Expensive |

| Steering vectors | Control | Low | Concept | Supervised | Specific-ish | Cheap |

| Training data attribution | Understanding |

I currently work in policy research, which feels very different from my intrinsic aesthetic inclination, in a way that I think Tanner Greer captures well in The Silicon Valley Canon: On the Paıdeía of the American Tech Elite:

...I often draw a distinction between the political elites of Washington DC and the industrial elites of Silicon Valley with a joke: in San Francisco reading books, and talking about what you have read, is a matter of high prestige. Not so in Washington DC. In Washington people never read books—they just write them.

To write a book, of course, one must read a good few. But the distinction I drive at is quite real. In Washington, the man of ideas is a wonk. The wonk is not a generalist. The ideal wonk knows more about his or her chosen topic than you ever will. She can comment on every line of a select arms limitation treaty, recite all Chinese human rights violations that occurred in the year 2023, or explain to you the exact implications of the new residential clean energy tax credit—but never all at once. ...

Washington intellectuals are masters of small mountains. Some of their peaks are more difficult to summit than others. Many smaller slopes are nonetheless ja

Saving mathematician Robert Ghrist's tweet here for my own future reference re: AI x math:

workflow of the past 24 hours...

* start a convo w/GPT-o3 about math research idea [X]

* it gives 7 good potential ideas; pick one & ask to develop

* feed -o3 output to gemini-2.5-pro; it finds errors & writes feedback

* paste feedback into -o3 and say asses & respond

* paste response into gemini; it finds more problems

* iterate until convergence

* feed the consensus idea w/detailed report to grok-3

* grok finds gaping error, fixes by taking things in different direction (!!!)

* gemini agrees: big problems, now ameliorated

* output final consensus report

* paste into claude-3.7 and ask it to outline a paper

* approve outline; request latex following my style/notation conventions

* claude outputs 30 pages of dense latex, section by section, one-shot (!)

====

is this correct/watertight? (surely not)

is this genuinely novel? (pretty sure yes)

is this the future? (no, it's the present)

====

everybody underestimates not only what is coming but what can currently be done w/existing tools.

Someone asked why split things between o3 and 2.5 Pro; Ghrist:

...they have complementary strengths and each picks up

I enjoyed Brian Potter's Energy infrastructure cheat sheet tables over at Construction Physics, it's a great fact post. Here are some of Brian's tables — if they whet your appetite, do check out his full essay.

Energy quantities:

Units and quantities | Kilowatt-hours | Megawatt-hours | Gigawatt-hours |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 British Thermal Unit (BTU) | 0.000293 | ||

| iPhone 14 battery | 0.012700 | ||

| 1 pound of a Tesla battery pack | 0.1 | ||

| 1 cubic foot of natural gas | 0.3 | ||

| 2000 calories of food | 2.3 | ||

| 1 pound of coal | 2.95 | ||

| 1 gallon of milk (calorie value) | 3.0 | ||

| 1 gallon of gas | 33.7 | ||

| Tesla Model 3 standard battery pack | 57.5 | ||

| Typical ICE car gas tank (15 gallons) | 506 | ||

| 1 ton of TNT | 1,162 | ||

| 1 barrel of oil | 1,700 | ||

| 1 ton of oil | 11,629 | 12 | |

| Tanker truck full of gasoline (9300 gallons) | 313,410 | 313 | |

| LNG carrier (180,000 cubic meters) | 1,125,214,740 | 1,125,215 | 1,125 |

| 1 million tons of TNT (1 megaton) | 1,162,223,152 | 1,162,223 | 1,162 |

| Oil supertanker (2 million barrels) | 3,400,000,000 | 3,400,000 | 3,400 |

It's amazing that a Tesla Model 3's standard battery pack has an OOM less energy capacity than a typical 15-gallon ICE car gas tank, and is probably heavier to...

A subgenre of fiction I wish I could read more of is rationalist-flavored depictions of utopia that centrally feature characters who intentionally and passionately pursue unpleasant experiences, which I don't see much of. It's somewhat surprising since it's a pretty universal orientation.

For instance, and this is a somewhat extreme version, I'm a not-that-active member of a local trail running group (all professionals with demanding day jobs) that meets regularly for creative sufferfests like treasure hunt races in the mountains, some of whom regularly fly...

Pilish is a constrained writing style where the number of letters in consecutive words match the digits of pi. The canonical intro-to-Pilish sentence is "How I need a drink, alcoholic of course, after the heavy lectures involving quantum mechanics!"; my favorite Pilish poetry is Mike Keith's Near a Raven, a retelling of Edgar Allan Poe's "The Raven" stretching to 740 digits of pi (nowhere near Keith's longest, that would be the 10,000-word world record-setting Not a Wake), which begins delightfully like so:

...Poe, E.

Near a RavenMidnights

There's a lot of fun stuff in Anders Sandberg's 1999 paper The Physics of Information Processing Superobjects: Daily Life Among the Jupiter Brains. One particularly vivid detail was (essentially) how the square-cube law imposes itself upon Jupiter brain architecture by forcing >99.9% of volume to be comprised of comms links between compute nodes, even after assuming a "small-world" network structure allowing sparse connectivity between arbitrarily chosen nodes by having them be connected by a short series of intermediary links with only 1% of links bein...

From Brian Potter's Construction Physics newsletter I learned about Taara, framed as "Google's answer to Starlink" re: remote internet access, using ground-based optical communication instead of satellites ("fiber optics without the fibers"; Taara calls them "light bridges"). I found this surprising. Even more surprisingly, Taara isn't just a pilot but a moneymaking endeavor if this Wired passage is true:

...Taara is now a commercial operation, working in more than a dozen countries. One of its successes came in crossing the Congo River. On one side was Brazza

Peter Watts' 2006 novel Blindsight has this passage on what it's like to be a "scrambler", superintelligent yet nonsentient (in fact superintelligent because it's unencumbered by sentience), which I read a ~decade ago and found unforgettable:

...Imagine you're a scrambler.

Imagine you have intellect but no insight, agendas but no awareness. Your circuitry hums with strategies for survival and persistence, flexible, intelligent, even technological—but no other circuitry monitors it. You can think of anything, yet are conscious of nothing.

You can't imagine such a

Ravi Vakil's advice for potential PhD students includes this bit on "tendrils to be backfilled" that's stuck with me ever since as a metaphor for deepening understanding over time:

...Here's a phenomenon I was surprised to find: you'll go to talks, and hear various words, whose definitions you're not so sure about. At some point you'll be able to make a sentence using those words; you won't know what the words mean, but you'll know the sentence is correct. You'll also be able to ask a question using those words. You still won't know what the words mean, but yo

Out of curiosity — how relevant is Holden's 2021 PASTA definition of TAI still to the discourse and work on TAI, aside from maybe being used by Open Phil (not actually sure that's the case)? Any pointers to further reading, say here or on AF etc?

...AI systems that can essentially automate all of the human activities needed to speed up scientific and technological advancement. I will call this sort of technology Process for Automating Scientific and Technological Advancement, or PASTA.3 (I mean PASTA to refer to either a single system or a collection of system

When I first read Hannu Rajaniemi's Quantum Thief trilogy c. 2015 I had two reactions: delight that this was the most my-ingroup-targeted series I had ever read, and a sinking feeling that ~nobody else would really get it, not just the critics but likely also most fans, many of whom would round his carefully-chosen references off to technobabble. So I was overjoyed to recently find Gwern's review of it, which Hannu affirms "perfectly nails the emotional core of the trilogy and, true to form, spots a number of easter eggs I thought no one would ever find", ...

One subsubgenre of writing I like is the stress-testing of a field's cutting-edge methods by applying it to another field, and seeing how much knowledge and insight the methods recapitulate and also what else we learn from the exercise. Sometimes this takes the form of parables, like Scott Alexander's story of the benevolent aliens trying to understand Earth's global economy from orbit and intervening with crude methods (like materialising a billion barrels of oil on the White House lawn to solve a recession hypothesised to be caused by an oil shortage) to...

I enjoyed these passages from Henrik Karlsson's essay Cultivating a state of mind where new ideas are born on the introspections of Alexander Grothendieck, arguably the deepest mathematical thinker of the 20th century.

...In June 1983, Alexander Grothendieck sits down to write the preface to a mathematical manuscript called Pursuing Stacks. He is concerned by what he sees as a tacit disdain for the more “feminine side” of mathematics (which is related to what I’m calling the solitary creative state) in favor of the “hammer and chisel” of the finished theo

Why doesn't Applied Divinity Studies' The Repugnant Conclusion Isn't dissolve the argumentative force of the repugnant conclusion?

...But read again more carefully: “There is nothing bad in each of these lives”.

Although it sounds mundane, I contend that this is nearly incomprehensible. Can you actually imagine what it would be like to never have anything bad happen to you? We don’t describe such a as mediocre, we describe it as “charmed” or “overwhelmingly privileged”. ...

... consider Parfit’s vision of World Z both seriously and literally.

These are live

What is the current best understanding of why o3 and o4-mini hallucinate more than o1? I just got round to checking out the OpenAI o3 and o4-mini System Card and in section 3.3 (on hallucinations) OA noted that

o3 tends to make more claims overall, leading to more accurate claims as well as more inaccurate/hallucinated claims. While this effect appears minor in the SimpleQA results (0.51 for o3 vs 0.44 for o1), it is more pronounced in the PersonQA evaluation (0.33 vs 0.16). More research is needed to understand the cause of these results.

as of ...

This is one potential explanation:

- o3 has some sort of internal feature like "Goodhart to the objective"/"play in easy mode".

- o3's RL post-training environments have opportunities for reward hacks.

- o3 discovers and exploits those opportunities.

- RL rewards it for that, reinforcing the "Goodharting" feature.

- This leads to specification-hack-y behavior generalizing out of distribution, to e. g. freeform conversations. It ends up e. g. really wanting to sell its interlocutor on what it's peddling, so it deliberately[1] confabulates plausible authoritative-sounding claims and justifications for them.

Sounds not implausible, though I'm not wholly convinced.

- ^

In whatever sense this term can be applied to an LLM.

Venkatesh Rao's recent newsletter article Terms of Centaur Service caught my eye for his professed joy of AI-assisted writing, both nonfiction and fiction:

...In the last couple of weeks, I’ve gotten into a groove with AI-assisted writing, as you may have noticed, and I am really enjoying it. ... The AI element in my writing has gotten serious, and I think is here to stay. ...

On the writing side, when I have a productive prompting session, not only does the output feel information dense for the audience, it feels information dense for me.

An example of th

Terry Tao recently wrote a nice series of toots on Mathstodon that reminded me of what Bill Thurston said:

...1. What is it that mathematicians accomplish?

There are many issues buried in this question, which I have tried to phrase in a way that does not presuppose the nature of the answer.

It would not be good to start, for example, with the question

How do mathematicians prove theorems?

This question introduces an interesting topic, but to start with it would be to project two hidden assumptions: (1) that there is uniform, objective and firmly establ

The OECD working paper Miracle or Myth? Assessing the macroeconomic productivity gains from Artificial Intelligence, published quite recently (Nov 2024), is strange to skim-read: its authors estimate just 0.24-0.62 percentage points annual aggregate TFP growth (0.36-0.93 pp. for labour productivity) over a 10-year horizon, depending on scenario, using a "novel micro-to-macro framework" that combines "existing estimates of micro-level performance gains with evidence on the exposure of activities to AI and likely future adoption rates, relying on a multi-sec...

Nice reminiscence from Stephen Wolfram on his time with Richard Feynman:

...Feynman loved doing physics. I think what he loved most was the process of it. Of calculating. Of figuring things out. It didn’t seem to matter to him so much if what came out was big and important. Or esoteric and weird. What mattered to him was the process of finding it. And he was often quite competitive about it.

Some scientists (myself probably included) are driven by the ambition to build grand intellectual edifices. I think Feynman — at least in the years I knew him — was m

From John Nerst's All the World’s a Trading Zone, and All the Languages Merely Pidgins:

...Trading Zone: Coordinating Action and Belief, by Peter Galison discusses how physicists with different specialties live in different (social) realities and what happens when they interact.

(Galison’s article is worth reading in full, it’s wonderful erisology — a synthesis of two models of scientific progress: incremental empiricism (of the logical positivists) and grand paradigm shifts (of Thomas Kuhn and others).)

Experimentalists, theorists and instrument makers are all

Scott's The Colors Of Her Coat is the best writing I've read by him in a long while. Quoting this part in particular as a self-reminder and bulwark against the faux-sophisticated world-weariness I sometimes slip into:

...Chesterton’s answer to the semantic apocalypse is to will yourself out of it. If you can’t enjoy My Neighbor Totoro after seeing too many Ghiblified photos, that’s a skill issue. Keep watching sunsets until each one becomes as beautiful as the first...

If you insist that anything too common, anything come by too cheaply, must be bor

I find both the views below compellingly argued in the abstract, despite being diametrically opposed, and I wonder which one will turn out to be the case and how I could tell, or alternatively if I were betting on one view over another, how should I crystallise the bet(s).

One is exemplified by what Jason Crawford wrote here:

...The acceleration of material progress has always concerned critics who fear that we will fail to keep up with the pace of change. Alvin Toffler, in a 1965 essay that coined the term “future shock,” wrote:

I believe that most human beings

Some ongoing efforts to mechanize mathematical taste, described by Adam Marblestone in Automating Math:

...Yoshua Bengio, one of the “fathers” of deep learning, thinks we might be able to use information theory to capture something about what makes a mathematical conjecture “interesting.” Part of the idea is that such conjectures compress large amounts of information about the body of mathematical knowledge into a small number of short, compact statements. If AI could optimize for some notion of “explanatory power” (roughly, how vast a range of disparate knowl

How to quantify how much impact being smarter makes? This is too big a question and there are many more interesting ways to answer it than the following, but computer chess is interesting in this context because it lets you quantify compute vs win probability, which seems like one way to narrowly proxy the original question. Laskos did an interesting test in 2013 with Houdini 3 by playing a large number of games on 2x nodes vs 1x nodes per move level and computing p(win | "100% smarter"). The win probability gain above chance i.e. 50% drops from +35.1% in ...

Just reread Scott Aaronson's We Are the God of the Gaps (a little poem) from 2022:

...When the machines outperform us on every goal for which performance can be quantified,

When the machines outpredict us on all events whose probabilities are meaningful,

When they not only prove better theorems and build better bridges, but write better Shakespeare than Shakespeare and better Beatles than the Beatles,

All that will be left to us is the ill-defined and unquantifiable,

The interstices of Knightian uncertainty in the world,

The utility functions that no one has yet wr

Lee Billings' book Five Billion Years of Solitude has the following poetic passage on deep time that's stuck with me ever since I read it in Paul Gilster's post:

...Deep time is something that even geologists and their generalist peers, the earth and planetary scientists, can never fully grow accustomed to.

The sight of a fossilized form, perhaps the outline of a trilobite, a leaf, or a saurian footfall can still send a shiver through their bones, or excavate a trembling hollow in the chest that breath cannot fill. They can measure celestial motions and l

What fraction of economically-valuable cognitive labor is already being automated today? How has that changed over time, especially recently?

I notice I'm confused about these ostensibly extremely basic questions, which arose in reading Open Phil's old CCF-takeoff report, whose main metric is "time from AI that could readily[2] automate 20% of cognitive tasks to AI that could readily automate 100% of cognitive tasks". A cursory search of Epoch's data, Metaculus, and this forum didn't turn up anything, but I didn't spend much time at all doing so.

I was originally motivated by wanting to empirically understand recursive AI self-improvement better, which led to me stumbling upon the CAIS paper Examples of AI Improving AI, but I don't have any sense whatsoever of how the paper's 39 examples as of Oct-2023 translate to OP's main metric even after constraining "cognitive tasks" in its operational definition to just AI R&D.

I did find this 2018 survey of expert opinion

which would suggest that OP's clock should've started ticking in 2018, so that incorporating CCF-takeoff author Tom Davidson's "~50% to a <3 year takeoff and ~80% to <10 year i.e. time from 20%-AI to 100%-AI, for cognitive tasks in the global economy" means takeoff should've already occurred... so I'm dismissing this survey's relevance to my question (sorry).

I am not one of them - I was wondering the same thing, and was hoping you had a good answer.

If I was trying to answer this question, I would probably try to figure out what fraction of all economically-valuable labor each year was cognitive, the breakdown of which tasks comprise that labor, and the year-on-year productivity increases on those task, then use that to compute the percentage of economically-valuable labor that is being automated that year.

Concretely, to get a number for the US in 1900 I might use a weighted average of productivity increases ac... (read more)