Honestly, I've come up with something like twenty conceptual buckets for future essays, and this one just happened to be the one that collected a dozen examples first; most of the essays in this sequence (if it gets written) will be of similar form. I think raw training data beats pared-down explanation at least half of the time.

(I'm reminded of Ben Pace saying that he never understood bucket errors until my essay that was primarily five examples in a row.)

$10 per example up to 10 examples, but please filter for some combination of grokkability and goodness; I'd like examples that are more like the stronger half of my set than the weaker half.

(This is about the example itself, not about how it's written up; writeups don't have to be long or in-depth or polished.)

It "deserves" much more than that but that's what I have to spare. Apologies for that fact (and no hard feelings if that price is too low to be worth your time).

A related spell is SCALO DISTINCTUS!

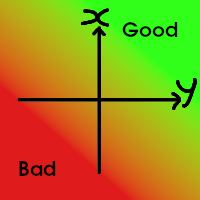

A spell that can turn this

Into

The spell works by splitting what we care about (x+y) into two distinct terms, x and y, and then implicitly taking the minimum by focusing on whichever part is worst.

The spell needs an implicit 0 for both x and y to work. But is a very powerful spell for picking your preferred point on any tradeoff scale, and refusing anything but a Parito improvement. I suspect the use of this spell is one of the main reasons TARE DETRIMENS! is cast at all. In a world with just 1 scale, people will pick the best option, wherever the zero lies.

One place I have seen this spell attempted is in environmentalism. The 0 is chosen as the world in caveman days. X and Y are chosen as X="the environment", and Y="human quality of life". If this casting succeeds, any improvement in human quality of life can never justify the slightest environmental harm, and we should all go back to a Malthusian harmony with nature.

A skilled caster will split the axes further. Whichever axis things are getting worse along should be subdivided into as many pieces as possible. In the environmentalism example, X should be subdivided into "carbon dioxide + pollution + loss of biodiversity + rising sea levels + running out of natural resources + species going extinct" And then you have 1 axis on which things are improving, and 6 axis along which things are getting worse. The multiplicity of axes also helps to distract from any one of them. Running out of natural resources (like copper ore) is something that would effect human quality of life, not harm the environment, but it can still be pulled away out of Y and into its own axis to fight for team X. Now you have a whole army on the side of X all picking on a single Y, be sure to associate Y with the most negative concept you can find "private jets and technowhiz gagets you don't really need" and victory is almost assured.

In the environmentalism example, X should be subdivided into "carbon dioxide + pollution + loss of biodiversity + rising sea levels + running out of natural resources + species going extinct" And then you have 1 axis on which things are improving, and 6 axis along which things are getting worse.

Example from Bloomberg today:

We’re Succeeding on Climate. We’ll Fail on Biodiversity

Single-issue environmentalists have a series of issues teed up. They've allowed climate change to be almost the monofocus in major media for a long time, because it really is the most pressing issue. Now that we're starting to make obvious progress, with a recent news article noting that it's becoming cheaper to build solar than to buy just the fuel for a natural gas station, it's time to start teeing up the next issue. Insofar as we appear to be making real progress on climate change, expect to see other environmental problems come to the fore.

It's not that these problems aren't real. It's that successful political activists are those who know how to think strategically about how to position their most important and tractable issue, and how to transition to new issues when the old ones get addressed.

Insofar as a political issue is progressively solved, expect to see some people who'd formerly focused on it drift away to other causes. Those who are left will be those who have the most singleminded focus on that specific issue. They will be smaller and have less ability to get things done, but if you ask them, they'll always have the next disaster to work on - because to them, there is only one issue.

The benefit I think we can hope to get by consulting political activists is to find out the most pressing issue in the domain they care about. By talking to environmentalists, we can find out what the most pressing environmental issue is today (climate change). By talking to gender activists, we can find about about the most pressing gender issue (probably rape or trans rights). By talking to YIMBYs, we can find out about the most important urban planning issue (housing).

But we can't find a nuanced discussion on how to prioritize between issues, or learn very much accurate information about the world, because both of these discussions will be subsumed within the political activists to the advancement of their agenda. This is normal and as long as we recognize it, we can still engage productively with even single-issue activists. There is probably a rich discussion to be had on how they prioritize their agenda.

Broadly an overall point that makes sense and feels good to me.

Something feels off or at least oversimplified to me in some of the cases, particularly these two lines of thinking:

There's no substantive disagreement between me and critics-of-my-blocking-policy about the difficulties that this imposes—the way it makes certain conversations tricky or impossible, the way it creates little gaps and blind spots in discussion and consensus.

&

As far as I could tell, both I and the admin team agreed about its absolute size; there were no disagreements about things like e.g. "broken links to previously written essays are a pain and a shame."

I found myself not actually trusting that there was "no disagreement about" about the nature or size in these cases. Maybe I would if I had more data about each situation, but something about how it's being written about raises suspicion for me. It's not per se than I think there was disagreement, but that I think the apparent agreement was on the level of the objective details (broken links etc) but that you didn't know how each other felt about it or what it meant to each other, and that if you'd more thoroughly seen the world through each others' eyes, it wouldn't seem like "zero point" is the relevant frame here.

One attempt to point at that:

It seems to me that without straightforward scales on which to measure things, or even getting clear on exactly what the units are, "setting the zero point" isn't even a real move that's available (intentionally or not) and I would expect people discussing in good faith to nonetheless end up with differences as a result of those.

Taking the latter case in particular, it seem likely to me (at least based on what you've written) that the LW admins were mostly tracking something like a sense of betrayal of expectations that people would have about LW as an ever-growing web of wisdom, and that feeling of betrayal is their units. And you're measuring something more on the level of "how much wisdom is on LW?" And from those two scales, two different natural zero points emerge:

- in removing the posts, LW goes from zero betrayal of the expectation of posts by default sticking around to more than zero betrayal of the expectation of posts sticking around

- in removing the posts, LW goes from more-than-zero wisdom on it from everybody's posts to less-than-before-but-still-more-than-zero wisdom on it with everybody's posts minus the Conor Moreton series (and in the meantime there was some more-than-zero temporary wisdom from those posts having gone up at all)

I noticed I ended up flipping the scales here, such that both are just zero-to-more-than-zero, even though one is more-than-zero of an unwanted thing. Not sure if that's incidental or relevant. Sometimes I've found in orienting to situations like this, one finds that there's only ever presence of something, never absence.

I'm not totally satisfied with this articulation but maybe it's a starting point for us to pick out whatever structure I'm noticing here.

Ah this comment from facebook also feels relevant:

Sam Harris’ argument style reminds me very much of the man that trained me, and the example of fire smoke negatively affecting health is a great zero point to contest. Sam has slipped in a zero point of physical health being the only form of health which matters. Or at least the highest. One would have to argue against his zero point, that there are other values which can be measured in terms of health greater than mere physical health associated with fire. Psychological, familial, and social immediately come to mind. Further, in the case of Sam, famed for his epistemological intransigence, one would likely have to argue against his zero point of what constitutes rationality itself in order to further one’s position that physical health is very often a secondary value, as this sort of argument follows more a conversational arrangement of complex interdependent factors, than the straight rigorous logic Sam seemingly prefers

A lot of what's going on here is primarily frame control—setting the relevant scale on which a particular zero is then made salient. And that is not being done in the nice explicit friendly way.

He's not casting the sneaky dark-arts version of the spell

Sam Harris here is not casting a sneaky version of Tare Detrimens, but he's maybe (intentionally or not, benevolently or malevolently) casting a sneaky version of Fenestra Imperium.

Huh—it suddenly struck me that Peter Singer is doing the exact same thing in the drowning child thought experiment, by the way, as Tyler Alterman points out beautifully in Effective altruism in the garden of ends. He takes for granted that the frame of "moral obligation" is relevant to why someone might save the child, then uses our intuitions towards saving the child to suggest that we agree with him about this obligation being present and relevant, then he uses logic to argue that this obligation applies elsewhere too. All of that is totally explicit and rational within that frame, but he chose the frame.

In both cases, everyone agrees about what actually happens (a child dies, or doesn't; you contribute, or you don't).

In both cases, everyone agrees because within the frame that has been presented there is no difference! Meanwhile there is a difference in many other useful frames! And this choice of frame is NOT, as far as I can recall, explicit. Rather than recall, let me actually just go check... watching this video, he doesn't use the phrase "moral obligation", but asks "[if I walked past,] would I have done something wrong?". This interactive version offers a forced choice "do you have a moral obligation to rescue the child?"

In both cases, the question assumes the frame, and is not explicit about the arbitrariness of doing so. So yes, he is explicit about setting the zero point, but focusing on that part of the move obscures the larger inexplicit move he's making beforehand.

I like and agree with your argument here in general.

I don't think it's true that, in the specific LW case, "...you didn't know how each other felt about it or what it meant to each other, and that if you'd more thoroughly seen the world through each others' eyes, it wouldn't seem like 'zero point' is the relevant frame here."

Or at least, none of what you said about the LW admin perspective was new to me; it had all been taken into account by me at the time. (I suspect at all times I was capable of passing their ITT with at least a C+ grade; I am less sure they were capable of passing mine.)

But that individual case seems separate from your overall point, which does seem correct. So I'm not sure where disagreement lies.

Reading this, I remembered my usual reaction to what you call "setting the zero-point", which serves as a pretty good defense spell. (I don’t normally think of it as a defense; it's just my go-to lens that I apply to most conversations that help me care about them at all).

My reaction is to identify and name the thing that the person seems to care about that’s behind the setting the zero-point. You could call it “Name The Value” (though "value" is kind of a loaded term, imo).

(this move is also available when anyone is complaining about anything, which is super handy)

Generally, from there, there's an exploration of why the person cares about this thing in particular (really seeking to understand what it would be like to be a person who cares about such things) and then, after that, maybe I'll introduce some other values that I think are also worth considering within the original question, just to taste ‘em together.

(You usually can't skip to introducing other values until the person feels heard on their underlying value. I mean, you can, but they'll probably feel bad, and people tend to clam up when they feel bad, which makes further conversation-of-the-type-I-want-to-have more difficult).

Most importantly for me, this conversational move tends to shift us from speculation about the world (which often requires being able to recall facts and information, which I’m bad at) and into a realm that allows for in-the-moment observation: the realm of What People (Say They) Care About.

(Actually, it’s richer than just What People (Say They) Care About— it’s how people orient to the world; what people find salient; what kind of mental schemas they keep; what sort of mental complexity they operate at; etc. There’s a lot of cool stuff hidden behind what people say and how they say it.)

New examples from discussion elsewhere:

"Oversharing"

"The notion of 'opportunity cost' subtly sets the zero point at optimal behavior, effectively painting all actually possible behaviors as in the red."

Whether billionaires are assumed to be "stealing" money from the rest of us by default.

"Earning a living" assumes that by default you die and that without direct compensation you do not deserve your upkeep.

(I notice a feeling that what moves are categorised as shady moves feel like setting the zero in themselfs. This has a high likelyhood of being the kind of "irressponcible metaspinning" that the forewarning is about)

My take on the removal of essays from LessWrong:

But there was a large disagreement about the implicit defaults. About whether the removal was a regrettable reduction in some large positive number, or whether it was breaking something, taking something, driving some particular substat of the overall LessWrong revival from positive to negative.

I can't promise I wasn't also doing the thing you describe here (I don't remember everything I said and would not be surprised if I don't endorse all the ways I've ever phrased my complaining about this).

But my frame on what I remember being the main takeaway was:

"Ah, I thought Duncan was someone who was reasonably committed to building a collective thing together, such that I could safely build public goods on top of what he had built, such that there was a larger edifice that I, and others, could depend on. I had thought that was a thing Duncan was explicitly trying to contribute to, in his own self image. Now, that seems false."

So, later, when I said "I couldn't trust you again after you removed all your essays from LessWrong abruptly", I don't mean "Duncan did a generically bad thing", I mean "Duncan did a thing that violated my expectations I had build around Duncan, which I thought Duncan been explicitly setting."

(I might be wrong that you had intended to explicitly set such expectations, and my recollection of what was going on in your life at the time also makes me feel fairly sympathetic to "yeah I did intend to set those expectations of shared-build-ability, but I needed to renege on that because having the essays up was surprisingly costly to me." I agree people do generally have the right to take their LW essays down, the thing at stake is "do they get to take their essays down, and still be thought of as a reliable community contributor")

(aside: I recall us communicating by email about this at the time, but couldn't find the email last time I checked. If you happen to have easy access to it and could re-forward it to me I'd appreciate that for the record. I might have already asked you about this and you said you couldn't find it)

Note that on this one, I tried to signal (with "(because I was caught in the grips of my own unquestioned assumptions about where the zero point lay)") that I think we were both attempting to set a zero point without explicitly declaring or defending it; I don't think either side was exhibiting this vice much worse than the other.

I think there's a thing here of, like ... if a man suddenly physically assaults his spouse, and the spouse then leaves, we do not usually say that the spouse is the one who dissolved the marriage, even though the spouse is the one who technically performed the "end the marriage" game action?

Like, we generally acknowledge that, to the extent that there is fault or blame for the fact that the marriage is over, it lies on the man who assaulted his spouse.

Similarly, I don't think it's fair to model me as not "reasonably committed to building a collective thing together, such that I could safely build public goods on top of what he had built, such that there was a larger edifice that I, and others, could depend on." I think that was absolutely 100% the thing I committed to in my marriage vows, metaphorically speaking.

And what Rankled was that it seemed to me that no one on the LW admin team credited "there's vicious libel of Duncan up on our site, being highly upvoted, and for a period of at least nine straight days no mod or admin can be bothered to even poke their head in" as being the equivalent of the man assaulting his spouse.

Like, from my perspective, the LW position at the time was "yeah, I know you're being beaten by your spouse, but come on, you married him; if you leave now you're definitely defecting."

I never thought I would need to explicitly state, as a precondition of my contribution to building a collective thing together, that it was conditional on stuff like "you won't be left utterly undefended for well over a week by the people to whom you are contributing your free and substantial labor, while meanwhile patently ridiculous abuse of you is upvoted and hosted on their platform."

Or in other words: the husband whose spouse leaves him and then says "what! This violated my expectations about our marriage, which I thought my spouse was explicitly and intentionally setting!" seems to me to be technically correct but overall wrongheaded. I don't think the spouse leaving should lose their reputation as a reliable partner, and I don't think that I, pulling my essays, deserved to lose my reputation as a reliable community contributor. I think the moment of trust-breaking lay earlier, and in a different place, than my "abrupt" removal of my essays.

(I'd been begging for help for over a week, and the team just ... felt it had more important things to do than help me. I was on their list, but in the course of that week my plight never managed to make it to anyone's top priority.)

EDIT: it feels weird to note that I'm upvoting all of Ray's commentary thus far because it deserves upvotes, but it feels weirder not to note it? It also feels weird to note, like, feeling well-held and well-treated by the LW admin team in the years since, while talking about this old and not-fully-resolved grievance, but that too is important context.

(I haven't read this carefully because I generally find it hard to participate in this class of convo with Duncan without it wrecking my weekend. I think this is largely a fact about me. I think I have things worth saying despite that, but flagging)

a) I don't think the timing described here checks out. I believe you took your stuff down on the same day LW 2.0 launched formally, which was in March. Defense of Punch Bug, which I think is the discussion you're referring to, happened in May, and was crossposted by Davis presumably because you had stopped crossposting your own stuff.

(My recollection is your motivation for pulling was the discussion of Dragon Army + a slow bleed of (probably?) less prominent things that added up to an overall pattern of LessWrong being bad for you)

This isn't particularly cruxy for me – I think I'd have approximately the same reaction to either set of motivations.

b) I don't mean it to be a huge judgment that I stopped thinking of you as reliable-for-Ray's-purposes. Like, it seems like a longstanding thing is we don't quite live up to each other's standards of what we think reliable should mean, and that's okay (albeit slightly tragic).

It matters what the extenuating circumstances are, kinda. It matters whether the LW team personally wronged you, or whether the ecosystem collectively wronged you. But, not much? I had had a model that the set of pressures you were facing wouldn't lead you to withdraw all your essays. That model was falsified, and that changed my plans.

There's probably more stuff I could say here that's worth saying, but I expect it to be fairly costly and time-intensive to dig into For Serious, and not really worth doing in a half-hearted way. (concretely: I'd continue this conversation if it were important to you but it'd be a "okay Ray and Duncan set aside a 4 hour block to put in some kind of serious effort" deal)

Mmmm, seems like I am cross-remembering, then, yeah. Sorry. The core thing, though, was "basically no one will protect you on LW; basically no one will stand up for what's right; basically no one will stand up for what's true; basically, people will just allow abuse to extend infinitely, and the people who are doing anti-truth are the ones in power and the ones getting socially rewarded."

If I actually reached the breaking point on all that in March, and took my stuff down, and then the Benquo stuff happened two months later on top of that, that ... doesn't exactly make that problem feel less bad.

No bid for four hours of your effort at this time.

Er. I notice myself again sort of setting the zero point in the above, with words like "libel"! Sorry.

To clarify: I felt genuinely threatened when a prominent, well-respected Jewish member of our community strawmanned my point into accusations of, quote, wanting to ghettoize people—that's quite powerful and explosive speech.

That sense of threat grew no smaller when that commentary was rapidly upvoted into middling double-digit territory and nobody felt like saying "this is not at all what Duncan's words mean?"

It was after over a week went by and no one seemed to think that this was urgent enough to need any publicly visible response at all that I "abruptly" pulled the essays.

I like this article a lot. I'm glad to have a name for this, since I've definitely used this concept before. My usual argument that invokes this goes something like:

"Humans are terrible."

"Terrible compared to what? We're better than we've ever been in most ways. We're only terrible compared to some idealised perfect version of humanity, but that doesn't exist and never did. What matters is whether we're headed in the right direction."

I realise now that this is a zero-point issue - their zero point was where they thought humans should be on the issue at hand (e.g, racism) and my zero point was the historical data for how well we've done in the past.

The zero point may also help with imposter syndrome, as well as a thing I have not named, which I now temporarily dub the Competitor's Paradox until an existing name is found.

The rule is - if you're a serious participant in a competitive endeavor, you quickly narrow your focus to only compare yourself to people who take it at least as seriously as you do. You can be a 5.0 tennis player (Very strong amateur) but you'll still get your ass kicked in open competition. You may be in the top 1% of tennis players*, but the 95-98% of players who you can clean off the court with ease never even get thought of when you ask yourself if you're "good" or not. The players who can beat you easily? They're good. This remains true no matter how high you go, until there's nobody in the world who can beat you easily, which is like, 20 guys.

So it may help our 5.0 player to say something like "Well, am I good? Depends on what you consider the baseline. For a tournament competitor? No. But for a club player, absolutely."

*I'm not sure if 5.0 is actually top 1% or not.

This is a great thread for explaining how to spot the frame

I have a lot to say on frames, but a very foundational lesson also worth mentioning is how the spell casting takes place, and how to Counterspell

It happens in 5 steps

- Someone sets a frame

- Significance control: thread expand if you agree, VS thread minimize if you decide to ignore it and move

- Frame negotiation: agree, reframe, or set your own (opposing) frame

- Agreement

- Cementing

If you set the frame, you can control the frame from beginning to end. However, if someone else sets the frame, then you first want to decide whether to expand on that frame, or to minimize it.

Significance Control

The more significant a frame is, the more it impacts the conversation, so whether you want to minimize or expand is an important decision

If you decide to challenge a frame, you also expand on it. So if you lose that negotiation, then you face much bigger consequences because you first expanded it, and then lost it. Indeed the opposite of minimizing is not to say it doesn’t matter but, often, is to simply ignore it.

Thread-Expanding

If a frame is agreeable to you, you want to expand on it. There are many ways of thread-expanding, including:

Asking questions such as “why is that” or “why do you think so” Asking leading questions: ie. “oh wow, do you really think so” Strategic disagreement: such as “you think so? But this other person said the opposite”. Now they’re forced to defend and talk more, which expands the initial frame Laughing: a way to “covert expanding” anyone with a Facebook account is familiar with. This is what lawyers sometimes do to highlight the opposing lawyers’ mistakes (you could see plenty of that during the Depp VS Heard defamation case: most people never realize that most of the snickering was done on purpose to sway public and jurors’ opinions) Agreeing and expanding: you agree, and explain why you agree Agreeing and sharing: you agree, and share a story that supports the frame or belief Agreeing and rewarding: you agree, and you tell them why you appreciate them for saying or doing what they did

(Side note: Most techniques of frame negotiation also expand on a frame. So you want to be careful not expanding disagreement or irreconcilable differences when you need rapport. And this is why, generally speaking, “agreeing and redirecting” is a fantastic form of frame control: it’s because it sets your own frame while minimizing the disagreement and leveraging the commonalities)

Thread-Minimizing

Whenever a frame is disagreeable to you, you can either challenge it, or minimize it

If you have the power to challenge it and change people’s opinions, or at least if you want your disagreeing voice to be heard, then you can speak up.

Many other times, it’s best instead to minimize a frame, and move on. Minimizing a frame includes:

Ignoring it "Yeah yeah-ing it”, such as to agree but with little to no conviction and then moving on Thread-cutting (ie.: Changing topic) a common, and effective technique (if well executed) Offer small and partial third-party agreement: ie.” yeah, some people feel that way”, and then moving on

Cementing

Now for the most important step

Imagine you agreed on a good frame that’s good for you. What do you do now?

You want to expand on that frame to increase the (perceived) benefits and the follow-through.

This phase is called “thread cementing”, an incredibly useful technique.

Frame cementing means: Expanding and solidifying the thread of the “agreement reached” to solidify the new frame and increase its effectiveness. Frame cementing increases the likelihood that the other party will stick to the new negotiated frame, and/or it increases the likelihood that the Persuasion will be internalized and accepted as the new reality (VS just agreeing with the frame as a form of short-term capitulation)

This final step... actually has additional substeps (Human psychology is hard, okay?!!!)

-

You reach a point where a frame is agreeable to you

-

Cement it by asking for confirmation

A frame that is agreed by the other party immediately increases its power by 10 fold. It makes people feel part of the decision, which increases adoption and followthrough, as well as increasing “intrinsic motivation”.

Some ways of doing it: • “ What do you think“: an agreement with less nudging gets more buy-in and is even more powerful • "Do you agree“ • "It makes sense, doesn’t it”

Note: silence often (thougb not always!) means one is in the process of accepting it, but might feel disempowered to admit it. Generally speaking, the frame agreed upon should feel good

- Cement it by providing your own confirmation

Confirm your own agreement about the frame and, ideally, also confirm it by sharing your good feelings about the new frame

For example: ▪︎ “I’m glad we agree“ ▪︎ “ I’m happy we see things the same way“

- End with a collaborative frame and/or reward

For example: • “Yeah, it makes sense, right? You get it because you’re also a smart guy/gal“ • “ I’m glad we’re going to do this. And I’m glad it’s going to help (because I care about you)“: show that you are glad about the new frame/agreement because it will benefit them, and because you care about them. Super powerful. But be honest about it please -or don’t say it-! • Silence and smile: confirms nonverbally the good vibe

- Next steps and taking action

If it was a frame that requires taking action, move on to the next steps.

(Side note: The more you had to persuade, the more you want to show that you are also tasking yourself with some steps. Eg “Great, so you can take care of X, I’ll do Y and Z, and we’ll meet at 4pm“)

Frame cementing is super powerful, BUT you better be genuine when using, and you better use it with real win-win frames or with the best intentions for the people you’re persuading.

When you use it for win-lose, that’s the stuff of manipulators. And albeit it can work in the short-term, over the long-term many people will catch on. As a matter of fact, the higher the quality of the people you deal with, the more likely it is they will catch on

Even when you use it for win-win you must be careful. You can still come across as a bit too sleek, which raises some red flags

Give people space to agree by themselves. Ask questions more than making statements. And when you must intervene, live by the motto "nudge, don’t push".

Also make sure you stress the win-win nature of the agreement, together with how glad you are because you care about them.

One final Warning: Unchallenged Frames Self-Cement Over Time

This is important to remember

Frames that go unchallenged tend to cement themselves. Especially when they repeat over time.

What happens is that the frame, from a verbal or nonverbal statement that simply describes or comments on reality, becomes more and more a reality of your shared (social) life.

This is a very important principl, because it means that if you let bad frames go unchallenged, then you lose arguments and/or persuasive power forever, not just in the few seconds that the frame lasts. And if they are repeated frames, they can also compound power over time

This is a similar principle for micro-aggressions: if you let micro-aggressions go unchallenged, then they build-up, and you die by a thousand cuts.

This usuallg means that it’s a good idea to get in the habit of challenging most frames are irrational/disagreeable early on in every new relationship

This doesn't sound wrong exactly but it does sound icky.

It seems to be missing "we are talking to each other in good faith, cooperatively; we point out the existence of the frame choices rather than sneakily trying to end up with a frame that's good for what we want right now".

I mean it's technically kindasorta there in some of the expanding, like “you think so? But this other person said the opposite”. But the spirit still seems adversarial and manipulative, even in "win-win". Like... "the only reason I'm not punching you is because you got lucky and accidentally agree with what I want".

If I used these techniques with myself it would feel like bad brain habits.

I don't want to be on the receiving end.

Maybe this is supposed to be applicable only in situations where you're fine treating people as NPCs to be manipulated? If so, add that context, on LW. If not -- FYI, it came off as if it was, to at least one person, namely me.

GuySrinivasan there are instructions on casting a dark spell, step by step

You don't cast Avada Kedavra with happy thoughts, you cast it with the intention to kill

You cast fiendfyre with blood

And you cast "TARE DETRIMENS" by having very bad brain habits, on average

This wasnt a guide for the purpose of doing it. This was a guide for the purpose of recognizing it when done to you and seeing them dance the steps and having them reified

If it wasn't "icky", why would it be a dark art?

Ah, I was confused the whole time.

how the spell casting takes place, and how to Counterspell

It happens in 5 steps

I thought you were trying to show us how to Counterspell! :D

Well, given the drop in upvotes, i can only imagine you weren't alone, so that's probably on me, should have made it clearer ;-)

I am wondering about the conditions where the zero would come from geometric rationality of some way to cognise the field.

I have approached similar things by explaining to myself that the zero relates to how unstated or new entrants to the system refer to the explicit content.

That is if zero is high then third options are aversed away from.

If the zero is super low then third options are strongly attracted to.

One of the options being at zero means that there are loads and loads of equivalent replacements for it or that we would be ambivalent to changing it to a unknown third option.

If you live on a street where there is a crash once a day, then hearing the first crash of the day is not really significant but kind of "it is Tuesday" acknowledgement. If you do not hear a crash that day, it is actually a good day. If you have a car crash once a year then having a car day is a bad day and not having one is a neutral day.

So status quo reference class tennis could largely end up being the same thing. One tool to understand different zero points would be to imagine what they claim about what "expected" looks like which might be easier than applying to the specific choice at hand.

I think this post successfully got me to notice this phenomena when I do it, at least sometimes.

For me, the canonical example here is "how clean exactly are we supposed to keep the apartment?", where there's just a huge array of how much effort (and how much ambient clutter) is considered normal.

I notice that, while I had previously read both Setting the Default and Choosing the Zero Point, this post seemed to do a very different thing (this is especially weird because it seems like structurally it's making the exact same argument as Setting the Default).

I think part of this was because some of the examples were things I had done (where I thought the situation was somewhat more complex than the abstraction Duncan included here, but where 'setting the zero point' was still clearly an important part of what was going on). I'm not sure if the post would have landed if I hadn't had more concrete arguments about specific instances that gave me a lot more handholds on what it's like to set a zero point.

Regardless, I think this post is more specifically pointed at "help the reader understand when they might have done this, in a dark-artsy way", then the previous Scott post.

Rereading this post + Scott's also reminds me of John Wentworth's The Prototypical Negotiation Game, and Parable of the Dammed, which are about the cultural processes for changing zero points.

I think... it's both true that people don't notice zero-point-setting and it has Manipulative nature to it, but also I think cultures having zero-points is probably kinda important (from a "have relatively simple structures that people can rely on" standpoint), and I'm interested in followup work that tries to synthesize that with "but also, zero points are made up and sneaky".

I feel there is an important thing here but [setting the zero point] is either not the right frame, or a special case of the real thing, [blame and responsibility are often part of the map and not part of the territory] closely related to asymmetric justice and the copenhagen interpretation of ethics.

In the territory, bad event happens [husband hits wife, missile hits child, car hits pedestrian]. There is no confusion about the territory: everyone understands the trajectories of particles that led to the catastrophe. But somehow there is a long and tortuous debate about who is responsible/to blame ["She was wearing a dark hoodie that night," "He should have come to a complete stop at the stop sign", "Why did she jaywalk when the crosswalk was just 10 feet away!"].

The problem is that we mean a bunch of different things simultaneously by blame/responsibility:

- Causality. The actual causal structure of the event. ["If she'd worn a reflective vest this wouldn't have happened," "If your left headlight wasn't broken you'd have seen her."]

- Blame. Who should be punished/shamed in this situation. This question already branches into a bunch of cruxes about the purpose and effectiveness of punishment.

- Responsibility. What is the most effective way of preventing such events in the future? ["If we passed a law that all pedestrians wear reflective vests it would halve incidents like this", "How about we institute mandatory pedestrian-sighting courses for drivers, and not blame the victim?"]

People argue about the same event with different causal models, different definitions of blame, and different notions of responsibility, and the conversation collapses. Fill in your own politically-charged example.

Setting the zero point seems to be one "move" in this blame game [if the default is that all drivers take pedestrian-sighting courses, then you're to blame if you skipped it. if the default is that all pedestrians must wear reflective vests, then you're to blame if you didn't wear one.]

Example: Dividing the cake according to NEEDS versus CONTRIBUTION (progressive tax, capitalism/socialism,)

Dividing the cake according to RIGHTs versus LEVERAGE

Look I am being so meta. I am defining the zero on the defining of zero. Also I don't want to risk being in this tone for long.

Having complained a bit about the individual examples that relate-to-me, I do agree that the overall pattern here is real and important.

I feel some desire to cross-reference this with Orthonormal's "Choosing the Zero Point", which is some sense is the same concept but applied in a pretty different way.

FWIW I do agree that I was making the zero-point mistake in the blocking discussion (although I think at the time I was also annoyed that you weren't listing the things that were salient side-effects of blocking in your posts explaining why you blocked)

I sometimes exhibit the vice of, uh, responding to someone else's perceived zero-point setting by not bringing it into the explicit text of the conversation, and just ... zero-pointing harder in the opposite direction.

Working on doing that less, at least with people with whom I have any sort of enduring relationship at all.

I don't know how useful this is, but as an "incel" (lowercase i, since I don't buy into the misogynistic ideology) I can see why people would emotionally set availability of sex as a zero point. I speak from experience when I say depending on your state of mind the perceived deprivation can really fuck you up mentally. Of course this doesn't put responsibility on women or society at large to change that, and there really isn't a good way to change that without serious harm. But it does explain why people are so eager to set such a "zero point".

Thanks for the essay. Am I right to classify "setting the zero point" as a subset of framing? How would you relate these two concepts?

Post summary (feel free to suggest edits!):

‘Setting the Zero Point’ is a “Dark Art” ie. something which causes someone else’s map to unmatch the territory in a way that’s advantageous to you. It involves speaking in a way that takes for granted that the line between ‘good’ and ‘bad is at a particular point, without explicitly arguing for that. This makes changes between points below and above that line feel more significant.

As an example, many people draw a zero point between helping and not helping a child drowning in front of them. One is good, one is bad. The Drowning Child argument argues this point is wrongly set, and should be between helping and not helping any dying child.

The author describes 14 examples, and suggests that it’s useful to be aware of this dynamic and explicitly name zero points when you notice them.

(If you'd like to see more summaries of top EA and LW forum posts, check out the Weekly Summaries series.)

Context: I have hopes of assembling a full "defense against the dark arts" sequence. This essay will not necessarily be the very first one in the sequence, but it's One Of The Basic Spells To Defend Against, and it's the one I happen to have done the most data gathering on so it's getting written up first.

Convergent evolution: Setting the Default, by Scott Alexander; Choosing the Zero Point, by orthonormal; this essay differs primarily in having a lot of examples.

Preamble I: Defense Against the Dark Arts

By "Dark Arts," what I mean is taking actions which cause someone else to get lost inside an inaccurate map—making their map unmatch the territory in a way that is advantageous for you or disadvantageous for them.

i.e. doing things which cause them to think that reality is a certain way, when it is not—when, if they had all of the information and context and unpressured time to think and process, they would reach a very different conclusion from the one they've reached under the influence of the spell.

As a very simple, silly example, the actions of the king in The Parable of the Dagger are dark-arts-y in the sense that I intend. (If you haven't read it: it's short and very good.)

I'm not planning to make a fine distinction between spells cast maliciously (i.e. people who are deceiving with deliberate intent) and spells cast instinctively/reflexively (e.g. people who are bending the truth because of their own fears or biases). In practice, it's often quite difficult to distinguish between these two groups, especially in one-off or very occasional interactions, and intent is not particularly relevant to countering the local effects of a given attempt-to-confuse.

(Working around malevolent intent is more of a strategic concern, and DADA is more about tactics.)

As for "Defense," the first and foremost tool in one's toolkit is awareness. Recognition. Most dark arts get the bulk of their power from creeping in unnoticed—once you consciously realize that oh, this person is negging me (for instance), the spell loses most of its potency.

If the full sequence gets written, there will be more to say about various active mental and interpersonal motions that one can make to fend off Dark attacks, but for the sake of this essay, the goal is to give you a concept like "square" which will help you recognize a bunch of different objects out in reality that have more or less of the square-nature.

Preamble II: On The Healthy Use Of Labels

I'm a big fan of reification—the idea that crystallizing a concept makes you better able to recognize that concept in multiple places, and port your observations between those places, and develop generally applicable models and plans.

But there's a sad side effect of developing new conceptual handles, which is that, inevitably, some subset of people are going to act as if the concept is "real" and start fighting over "is it or isn't it?" in given instances.

Getting an autism diagnosis as an adult is useful because it suddenly gives you a new way to interpret your experiences, and a new search term to dig up resources. It promotes to your attention a set of people to talk to and tools to try out; learning that you're autistic means "things which help lots of autistic people are unusually likely to be helpful for you," which is way better than doing a random walk through the vast unsorted library of generically potentially helpful things.

Ditto, having a concept like "sealioning" can be super useful, because suddenly you can see the core mechanical nature of a Thing That Sometimes Happens, and recognize how it crops up in widely spaced contexts, and start to flesh out a set of reusable responses that you can port between those contexts rather than reinventing the wheel from scratch every time.

What's bad is if you take your new conceptual handle "sealioning" and end up going "ah, okay, the thing to do here is to decide Which Things Are Sealioning and Which Things Aren't, and then attack the former category and defend the latter (while fighting tooth-and-nail to make sure that none of my good-natured questioning gets mistakenly labeled as sealioning)."

Or if you take your new autism diagnosis and go "ohhh, I see! Now I have a handy-dandy curiosity-stopper and social shield; I can just throw up my hands and say 'it's because autism, now leave me alone.'"

(All of this is sort of abridged and hand-wavey; by rights this concept deserves its own essay and

hopefully it will get one somedayit got one!)In short: there's a failure mode, and it's something like asking "is this really X?" or getting into fights over which things qualify for the label or not.

("You're DARVO'ing!" "Oh, real nice, DARVO me by preemptively accusing me of DARVO'ing.")

But there's a good thing, which is: "what does having recognized its non-zero X-ness get me? What connections does it help me make, and what tools does it bring to mind, and what paths does it suggest?"

This essay is going to try to give you a new conceptual handle. Please use responsibly.

Setting the Zero Point

Okay, so. Two wizards are facing off against each other in dueling stances, perhaps with an audience of apprehensive onlookers, and one of them levels a wand and bellows TARE DETRIMENS!

What actually happens? What is "setting the zero point"?

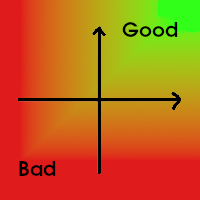

What usually happens, I claim, is that a number line which, out in the territory proper, looks like this:

...gets interpreted as being, fundamentally, something like this:

This is a huge difference, psychologically speaking. Populations which are bought into the second narrative will behave noticeably differently from populations which are bought into the first. Adding in a zero means that a slide from the right spot to the left spot is now crossing the boundary from positive to negative (or, in valence terms, from good to bad), where before it was just ... motion.

The story of a shift from 2 to -5 is way, way, way different than the story of a shift from 87 to 80, or from 32 to 25, or from 7 to 0, or from 1,376,219 to 1,376,212. The placement of the zero has tremendous impact on our collective sense of whether this motion was negligible, alarming, or downright catastrophic.

Typically, when someone is "trying" to set the zero point—

(Here I put "trying" in scare-quotes because, again, often this is instinctive rather than intentional.)

—they don't make a reasoned, explicit bid for taring the scale at this particular place. Typically, they simply proceed with their arguments as if it's obvious that the default boundary between good and bad (or positive and negative, or acceptable and unacceptable, or progress and regress) lies there. They'll take it for granted, and use word and phrasing choices that lean heavily upon that unstated assumption, and the "spell" that will either successfully ensorcel the other person (or the audience) or not is that point of view. If the attempt to set the zero point succeeds, everyone else's map quietly sprouts a zero in the desired place, and all the valences update accordingly.

It's that silence that makes this a dark art. That sneaky slipping-in of a frame, without acknowledgement or argument. It's the way that people don't even realize that the zero isn't actually out there, in the territory, and that their maps have been arbitrarily anchored on some otherwise undistinguished point—the way that they find themselves uttering phrases like "how am I supposed to compete with that?" as if something has gone wrong in a fundamental sense, if they can't.

(Often, both wizards are casting the spell at the same time, with different values of zero, and the question is which of them will overpower the other, or whose version of the line will ultimately feel more true and real to the relevant parts of the audience.)

It's all right if this hasn't quite clicked yet, because the bulk of the remainder of the essay is just a whole bunch of examples, from which you will (hopefully) be able to extract the pattern, such that you can start to recognize it out in the wild.

Example I: The Fireplace Delusion

Sam Harris has an excellent piece about instinctive rationalization in which he points out that we know, unambiguously, that there is no healthy amount of smoke inhalation, and that we know, unambiguously, that wood fires are bad for us.

In this piece, Sam Harris is explicitly arguing against a zero point. He's not casting the sneaky dark-arts version of the spell; he's trying to get people to notice that the spell has already been cast upon them, by our cultural narratives.

Sam Harris is pointing out that we've arbitrarily and erroneously set the zero point for fires too high, such that dropping down to zero actual fires feels like going into the negative. For many people, there's not an "aw, shucks, I liked fires! Oh, well" feeling, but rather a sensation of being robbed, pushed into dystopia, losing something crucial and precious. It feels bad. It feels like there's a "correct" number of fires to have in the fireplace or at the campsite every year, and it feels like that number is higher than "none," so "none" feels expectation-violating and worse-than-default.

(One could, of course, explicitly argue that low amounts of smoke inhalation are a price worth paying for a rare indulgence, but this is not what's actually happening in the brains of most people when they start up a fire, even after encountering the unpleasant facts.)

Example II: The Drowning Child

(We're easing into things; the examples will turn more Darkly manipulative soon.)

In his landmark thought experiment, Peter Singer (again more or less explicitly) argues that we have set our moral zero point in the wrong place. We erroneously believe, goes the argument, that there is some moral insulation provided by physical distance, a kind of out-of-sight discount that lets us off the hook.

We believe, in other words, that if a child dies in the distant poverty-stricken third-world, of some ailment that we could theoretically have prevented, then sure, life has gotten a little sadder, but it's not like it's gone all the way from good to bad—and it's definitely not the case that we have gone from good to bad!

Peter Singer is arguing that we've made a mistake: that, if we would say you crossed a moral line by refusing to rescue a drowning child right in front of your eyes, then you have also crossed the same moral line if you refuse to make a similarly-sized sacrifice to save a child who merely happens to have the misfortune of being far away.

In both cases, everyone agrees about what actually happens (a child dies, or doesn't; you contribute, or you don't). The difference is how that delta is interpreted—what valence attaches to it. Are you failing to take an opportunity to do optional extra good, or are you derelict in your moral obligations, and thus bad?

Example III: Blocking on Facebook

I'm relatively close to the center of the EA/rationalist/AI-safety communities, especially the ones based out of the Bay Area. Once in a while, a Rather Important Community Discussion™ will happen on my Facebook wall; other times, my own comments on other people's posts will spark long subthreads with many people chiming in.

I also have a relatively unusual blocking policy, which results in more blocks than average (e.g. all of my former superiors at CFAR). This means that sometimes, a Rather Important Community Discussion™ will happen, and many people will assume that so-and-so's non-participation in that discussion meant that they didn't care to comment or had nothing to say, when actually they were perhaps literally unaware that the discussion was taking place. Other times, someone will try to do a big common-knowledge creation post, and everything that happens under my own commentary on that post is hidden from an unknown list of participants in other comments on that post.

There's no substantive disagreement between me and critics-of-my-blocking-policy about the difficulties that this imposes—the way it makes certain conversations tricky or impossible, the way it creates little gaps and blind spots in discussion and consensus.

There's large disagreement, though, about whether those 5 units of disutility are taking some aggregate "us" from 87 to 82, or from 12 to 7, or from 2 to -3. There's large disagreement about where the zero point lies, which means there's large disagreement about whether this is a very small percentage shift, a large percentage shift, or a full valence shift in the sense that my blocking policy has taken us from "good" to "bad."

Another way to look at this is as a question of how much goodness can be taken for granted—what the default expectations of social smoothness and intercommunicability should be, whether it's reasonable to expect it to be easy to "get everyone in the same room," and, when it's not possible, who's to blame for it.

One side of this debate sets the zero point very far away, and holds something like "that we're even able to do this much communication is already a miracle; people doing self-protective blocking are, sure, taking us downward from some idealized imagined peak, but it's a few small minuses in a big pile of plus."

The other side sort of takes as default a state in which no Important Players are mutually invisible to one another and common-knowledge conversations are/should be easy to spin up at the push of a button, and thus my blocking policy is taking away from us all something that we had a collective right to expect in the first place.

It's the difference between labeling the loss of points a defection or not, in other words. Whether it counts as a defection depends on whether you assume we collectively owned this unhiccupped communication power in the first place, and had it taken away.

Example IV: "AI art harms artists!"

(Similar to "clean energy harms coal miners" and "self-checkouts harm cashiers.")

Previously, art was uniformly a laborious, high-skill process.

Now, it's only sometimes a laborious, high-skill process. Sometimes you can get the art you want by just feeding some words into a service like Midjourney or Stable Diffusion.

Two problems are emerging for artists, as a result.

One, many artists are being directly replaced, in that people are typing in prompts like "fantasy battle scene in the style of Seb McKinnon." The AI services have access to Seb McKinnon's artwork, because it's already publicly available in places that the AI scrapes from.

So now, someone who might've had to pay Seb McKinnon hundreds or thousands of dollars in commission is instead getting that sweet, sweet Seb McKinnon style basically for free, and Seb McKinnon is receiving no compensation.

The other problem is that art in general is suddenly becoming more plentiful and easier to create/access/acquire, meaning that the people who had embarked on a career path of being an artist, with the previously reasonable expectation that they could make some kind of a living doing so, are having the rug pulled out from under them.

This is a dot sliding badwards on a scale. But the question of whether this is "harm" depends on where one sets the zero point. One could set out to explicitly answer the question "is the loss of future expected income due to a shift in the technological landscape harm, or is it just a sort of 'those are the breaks' type situation?"

But usually, people don't debate the question on that level. They don't address the complex policy question of to what extent we should consider future expected income to, in a sense, already be in someone's pocket, such that taking it away is morally equivalent (perhaps with some discount) to taking money right out of their wallet.

Instead, they just set the zero point where they think it belongs, and argue as if that perspective is obviously correct and may be taken for granted (and as if anyone who disagrees is some kind of heartless monster or some kind of naive idiot, depending).

Example V: Strikes and Unions

Everyone acknowledges that when teachers, healthcare professionals, railway workers, or other critical laborers go on strike, a very bad and costly thing happens as a result. That's rather the point, from the perspective of the strikers: to remind people that they are, perhaps, undervaluing and undercompensating this very important work, and could use a nudge to repair unsustainable working conditions.

The valence of this bad thing, though, or where the blame lies, often breaks down into two distinct takes, based on where each side sets the zero point.

One side typically sets it at something like "this critically important work is, y'know, critically important; leaving society in the lurch is a major defection." The assumed default is that the doctors will show up to the hospital, the teachers will show up to the classroom, the trains will run on time, etc. That's the minimum; any individual or group who choose to make that not-happen is directly responsible for taking us from good to bad.

The other side typically focuses on things like "if this labor is so critical then why don't we compensate it competitively" and "dear god, these people have been struggling to get a couple of paid sick days for years, what is wrong with us as a society" and so forth. The zero point they're paying attention to is on a wholly different axis, one that hardly even cares about hospitals, students, or trains—instead, the question is what counts as sufficiently decent compensation, and a sufficiently decent work environment?

Both sides agree that the strike causes X amount of damage in terms of lives lost or students untaught or dollars drained away from the economy, but one side views this as taking a largely-functioning system and making it dysfunctional; the other views it as ripping the band-aid off a dysfunctional system such that it has to be restructured/repaired.

Or in other words, a marginal shift between shades of red, not a valence inversion.

Example VI: Police shootings of unarmed black men

This example is largely about shifting from negative to positive, and the placement of the zero point is about the victory condition of a current ongoing social evolution.

It is bad to be murdered. It's fairly common to feel that it's somehow worse to be murdered by an agent of the state—by the very people whose entire job is (ostensibly) to protect and serve you. It's even more universally held that it's yet worse to be murdered by government agents while completely innocent, holding no weapon and engaging in no crime. And the abhorrent icing on the horrible cake is that it's even worse still if the government agents aren't just going around murdering innocent people, but are particularly murdering innocent people of a single ethnic cluster, such as black men.

It took depressingly long for this problem to be promoted to the general attention of the whole society. Now that it has, the question is: where's the zero point, and how will we know when we've crossed it?

One side holds that the dividing line between "bad" and "good" is something like "any police murders of unarmed black men at all," and that we will know we have Solved The Problem when the police stop killing unarmed black men. Entirely.

The other side is often somewhat quieter, because it's sometimes hard to make subtle points without painting yourself into the company of deplorables. The other side whispers, though, that we're a country of over three hundred million people, that mistakes happen all the time, that there is such a thing as putting too much emphasis on one single problem among many, and that perhaps—perhaps—we could consider this problem solved if the police are killing unarmed black men at the baseline rate of tragic disaster, i.e. about as often, proportionally, as they kill unarmed white men or unarmed Asian men or unarmed Hispanic men, etc.

(Getting that baseline disaster rate down feels, to this group, like a separate and also worthwhile problem.)

Thus, as the situation slowly crawls from deep dark red to mere blood red to pale pink and onward and upward toward white and possibly even blue, the two sides disagree about how bad it is, how urgent the problem remains given that badness, and whether and when to say "this is enough; time to turn to other causes of death and suffering, now."

Which is tricky, because each of the two perspectives comes along with a lot of handy imagery and invective for damning and decrying the other side.

(Indeed, using that invective helps hammer home the point, that the zero point of this scale obviously lies where you think it lies, and not where they think it does, those savages.)

The point here is not so much "both sides have a claim to the truth!" Rather, it's this is where I think the conversation ought to focus, at least for a little while, at least ever, and in practice, it almost never does. Almost never do you get both sides sitting down with the intention of coming to mutual agreement about where the scale is tared; there's too much potential power to be found via blasting your own worldview at maximum volume.

(It would be a significant sign, I think, that your nation was actually creeping toward rationality, if both sides agreed to forego that potential power, and sit down and settle such questions first. If people were, on the whole, willing and able to disarm along this one axis, and make a sacrifice of the local advantage for the sake of the global good.)

Example VII: Conor Moreton and LessWrong

At one point, in the earliest days of the LessWrong 2.0 revival, I decided that the best way I could help out would be to write an essay every day for a month, so there would always be some new and at least plausibly interesting content.

At another point, for various reasons, I decided to pull those thirty pseudonymous essays, and withdraw from LessWrong, and asked the admin team to help close down the account (they did).

What I did not anticipate (because I was caught in the grips of my own unquestioned assumptions about where the zero point lay) was a large disagreement about the badness of this action. As far as I could tell, both I and the admin team agreed about its absolute size; there were no disagreements about things like e.g. "broken links to previously written essays are a pain and a shame."

But there was a large disagreement about the implicit defaults. About whether the removal was a regrettable reduction in some large positive number, or whether it was breaking something, taking something, driving some particular substat of the overall LessWrong revival from positive to negative.

To me, "zero" was something like "LessWrong doesn't exist," and "negative" would be something like "some anti-LessWrong is gaining traction and popularity."

My understanding of the admin team's position was something like: "zero" is where LessWrong was last week; the quality of the site and its collection of content is a constant upward ratchet; "negative" is any regression at all in the presently-accelerating process of its continuous growth.

(They are free to chime in to correct my caricature of their position; I don't mean to claim that I fully understood and have accurately represented their beliefs; the best I can offer is that I am not intending to strawman them. I mostly just mean to point to the fact that there was some big disagreement, and it seems to me that this disagreement was largely about what counts as zero. Where the dividing line between "good" and "bad" was, as opposed to the dividing line between "good" and "better" or "bad" and "worse.")

Example VIII: Incels

There are many different people who could honestly lay claim to the label "incel," and there's a wide range of behavior and philosophy under that label, not all of which is terrible.

But there are at least some people who publish, under the label "incel," a philosophy that seems to boil down to something like: every human deserves physical intimacy; the default is that everyone should get to have sex; to the degree that some of us are unwillingly denied sex, something has gone actively wrong and someone—

(Usually either "women" or "society," though it's important not to lose track of the fact that there are many women and nonbinaries who are involuntarily celibate and indeed the term was coined by a woman, to describe her own situation, as part of a process of actively seeking to understand and solve the problem)

—is to blame.

Most other people hold that yes, indeed, being involuntarily celibate is bad, it's approximately just as bad as the incels say it is, let's call it -1000 on some arbitrary scale, but that -1000 isn't enough to go from life is good to life is bad, and furthermore even if it were, it's not anybody's job to solve this problem on behalf of any given individual.

Setting the zero point: have "women," as a class, taken something from men who can't find a sexual partner, such that their behavior is morally culpable en masse? Or is something else going on?

Example IX: Secular Solstice

There was one year in which a member of the Berkeley rationalist community (not a particularly prominent one; not one of the organizers of the Secular Solstice celebration) was going around arguing that if one did not attend and support the Secular Solstice celebration, one was actively defecting on the rationalist community, and doing direct damage to the social fabric.

Clearly this person's default assumption was something like "Secular Solstice is going well and universally attended." Anything less than that was in the red.

Example X: Location-based pay

You join a tech company in 2018. You move to San Francisco, or possibly Austin, or Seattle, or New York. Your pay is set higher than other hirees of comparable skill and experience, likely because the cost of living in those cities is known to be high, but there's no specific policy and no clause in your contract.

COVID hits. In early 2020, everyone switches to work-from-home. You continue doing the same excellent work you've been doing, with no drop in quality and no reduction in your rate of improvement as an engineer.

A year passes. Because you're no longer socializing, being in the Big City™ is no longer paying off in the way you expected it to. In early 2021, you move to a nice, quiet, idyllic property in Oklahoma.

Should the company dock your pay? Should you take a pay cut, because you've chosen to reassign some portion of your compensation from "housing" to "savings" or "a nicer television" or "having another kid"? To whom "belongs" that extra layer of compensation that you were given four years ago, that your company has clearly felt was worth giving you throughout a year of remote work—remote work which has taken no drop in quality from your move to Oklahoma?

Example XI: Clothing Norms

During all of the tribal signaling in 2020 and 2021, many people made the argument that no one should have the right to force you to put an uncomfortable piece of cloth over a part of your body—not if you didn't want to.

Many nudists laughed, grimly amused.

In late 2022, the women of Iran rose up in protest against their totalitarian religious government, casting off the hijab that was a symbol of that government's oppressive power over them. People throughout the democratic world cheered as they said "we will no longer allow you to dictate that we must cover this part of our body, when we do not want to cover it."

Many nudists laughed again.

Tops remain mandatory for women; pants remain mandatory for basically all people. The zero point is set somewhere below the hijab, and somewhere above underwear; whether mandatory masks count as positive or negative seems to depend a lot on one's tribal politics.

Example XII: Chick-fil-A

"If you still eat at Chick-fil-A, you hate gay people, are extremely selfish, have no moral fiber, etc" is a fairly common refrain.

There's an attempt to do something like ... impose a stag hunt? And make it so that choosing "rabbit" counts as defection, even though the stag hunt hasn't actually been argued persuasively and fully coordinated, and there's nothing even close to consensus agreement among queer people.

(Remember, absent actual agreement, the Schelling choice is rabbit.)

Personally, I often enjoy a Chick-fil-A sandwich after meeting up with my longtime male partner in North Carolina. I'm open to bids for a stag hunt, but taking for granted that purchasing a sandwich decisively moves you from "good person" to "bad person" is casting tare detrimens.

Example XIII: You're Ruining The Vibe

...was the vibe here first? Is it my job to make sacrifices on its behalf? Do the other people in this room have a "right" to some particular vibe, such that I'm taking something away from them, if that vibe can't survive my presence?

(Is it a defection to not-stand-up during a standing ovation??)

Sometimes yes, and sometimes no, of course, depending on all sorts of contextual detail. But it's interesting how the sort of person who actually utters phrases like "you're ruining the vibe" often does not seem to think such questions are worth asking, or are even possible to ask. The answers are usually assumed, and assumed to be nigh-universal, with such a degree of confidence that the speaker usually doesn't even notice they're assuming anything at all. It feels like the zero point is part of the territory itself.

Example XIV: Miscellany

What's the right amount of corporal punishment to deploy when raising children?

What's the right number of glasses of wine to have with dinner every night?

What's an appropriate number of years to be kept in compulsory schooling before you're allowed to try to start your adult life?

Occasionally, these and other questions are explicitly and openly discussed. But far more often, people take their own intuitive sense as default, and simply proceed as if it's obvious that their own cultural set-point is the correct one.

I once argued with a dark-robed Sith lord in the CFAR office, claiming that there was something bad about spending more than a few hours of video gameplay every day, on average. She made a confident bet that I believed this because I play video games for a couple of hours on the average day. She was wrong (my daily average in most years is zero), but it was the right bet to make!

Extrapolating the pattern

The thing that I'm pointing at is the feature common to all of the above examples, in which:

I'm currently calling this dynamic "setting the zero point" because I've spent eight months trying to think of a better name and have failed to find one (though you should feel free to use "Tare detrimens!" if you like; I do actually think it's fairly clever).

I claim that there is, in fact, a natural cluster here, but like all clusters, it's not perfect:

The key value, according to me, of learning to recognize when someone is making an argument that implicitly sets a zero point/takes a zero point for granted, is that you can:

Things that I am eager for, in discussion below:

Things I'm much less interested in, and will not join in on, though people are welcome to do them anyway:

... basically anything that's doing the "forget that constellations aren't real" thing.

Hope this helps,

—Duncan