Introduction

Two months ago I recommended the Apollo Neuro for sleep/anxiety/emotional regulation. A number of people purchased it based on my recommendation- at least 25, according to my referral bonuses. Last week I asked people to fill out a form on their experience.

Take-home messages:

- If you are similar to people who responded to my first post on the Apollo, there’s a ~4% chance you end up getting a solid benefit from the Apollo.

- The chance of success goes up if you use it multiple hours per day for 4 weeks without seeing evidence of it working, but unless you’re very motivated you’re not going to do that.

- The long tail of upside is very, very high; I value the Apollo Neuro more than my antidepressant. But you probably won’t.

- There’s a ~10% chance the Apollo is actively unpleasant for you; however no one reported cumulative bad effects, only one-time unpleasantness that stopped as soon as they stopped using it.

With Numbers

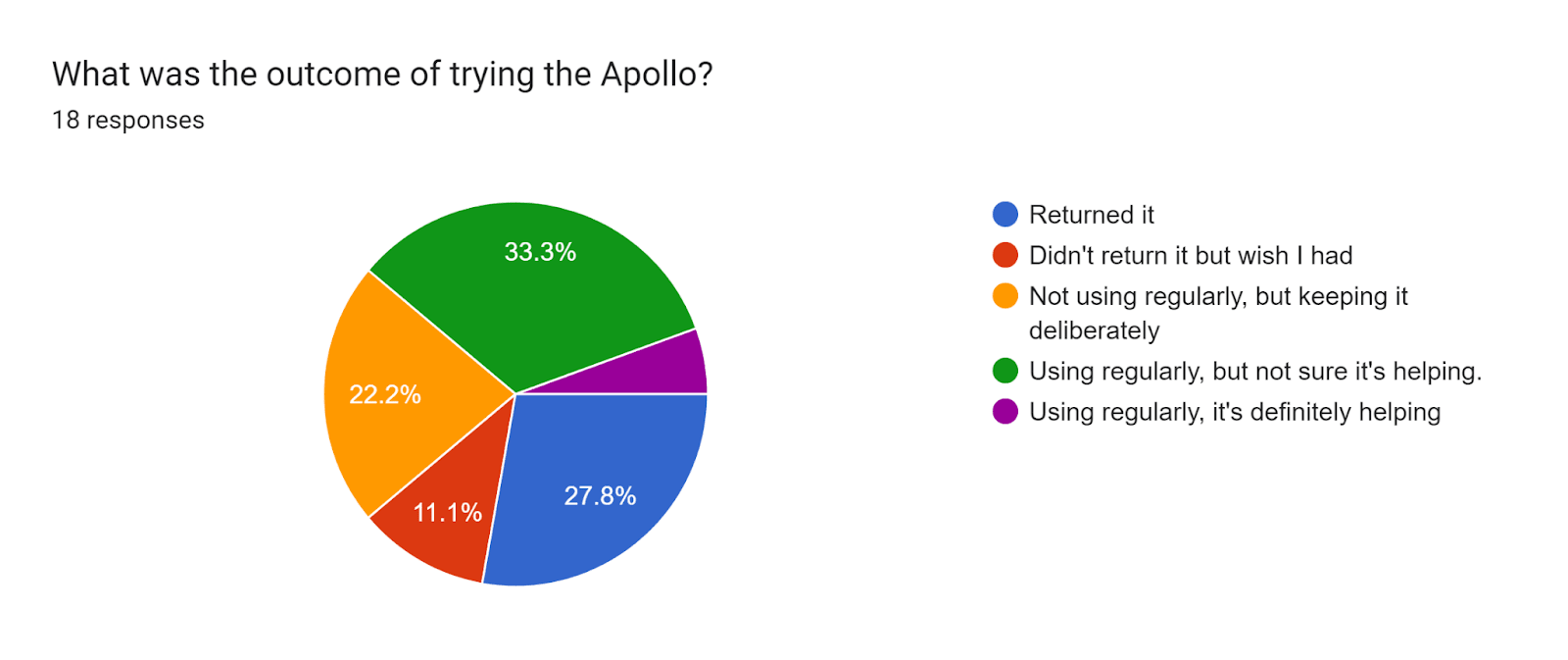

The following graphs include only people who found the Apollo and the form via my recommendation post. It does not include myself or the superresponders who recommended it to me.

(that’s one person reporting it definitely helped)

An additional six people filled out an earlier version of the form, none of whom found it helpful, bringing the total to 24 people.

Obviously I was hoping for a higher success rate. OTOH, the effects are supposed to be cumulative and most people gave up quickly (I base this on conversations with a few people, there wasn’t a question for it on the form). Some of that is because using the Apollo wasn’t rewarding, and I’ll bet a lot of the problem stems from the already pretty mediocre app getting an update to be actively antagonistic. It probably is just too much work to use it long enough to see results, unless you are desperate or a super responder.

Of people who weren’t using it regularly: 55% returned it, 20% failed to return it, and the remaining 35% chose to keep it. I think that last group is probably making a mistake; the costs of luck-based medicine add up, so if you’re going to be a serious practitioner you need to get good at cutting your losses. It’s not just about the money, but the space and mental attention.

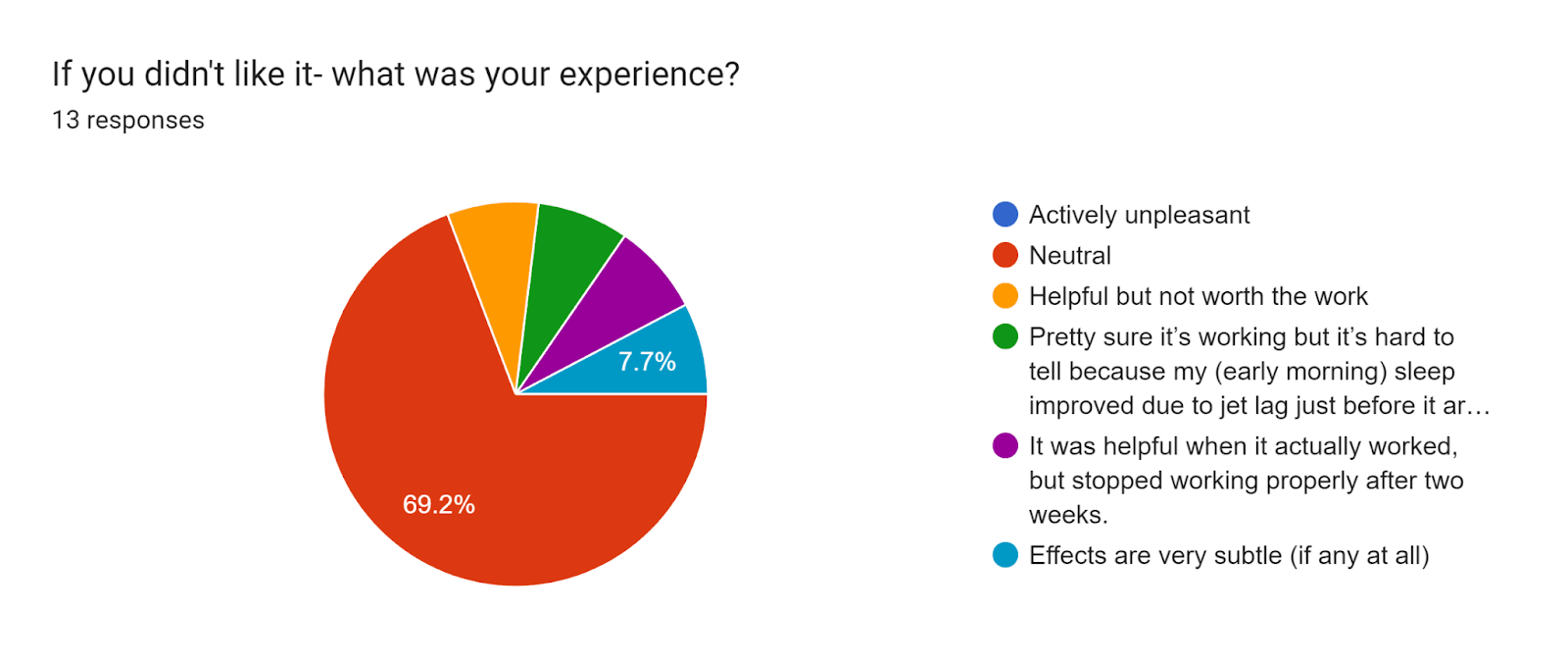

Of 6 people in the earlier version of the form, 1-2 found it actively unpleasant.

The downside turned out to be worse than I pictured. I’m fond of saying “anything with a real effect can hurt you”, but I really couldn’t imagine how that would happen in this case. The answer is: nightmares and disrupted sleep. In both cases I know of they only experienced this once and declined to test it again, so it could be bad luck, but I can’t blame them for not collecting more data. No one reported any ill effects after they stopped using it.

I would also like to retract my previous description of the Apollo return policy as “good”. You do get most of your money back, but a 30-day window for a device you’re supposed to test for 28 days before passing judgment is brutal.

It’s surprisingly hard for me to find referral numbers, but I know I spurred at least 25 purchases, and almost certainly less than 30. That implies an 80% response rate to my survey, which is phenomenal. It would still be phenomenal even if I’d missed half the purchasers and it was only a 40% response rate. Thanks guys.

Life as a superresponder

Meanwhile, the Apollo has only gotten better for me. I’ve basically stopped needing naps unless something obvious goes wrong, my happiness has gone up 2 points on a 10 point scale (probably because of the higher quality sleep)1, sometimes my body just feels good in a way it never has before. I stress-tested the Apollo recently with a very grueling temp gig (the first time in 9 years I’ve regularly used a morning alarm. And longer hours than I’ve maybe ever worked), and what would have previously been flat out impossible was merely pretty costly. Even when things got quite hard I was able to stay present and have enough energy to notice problems and work to correct them. The Apollo wasn’t the only contributor to this, but it definitely deserves a plurality of the credit, maybe even a majority.

When I look at the people I know who got a lot out of the Apollo (none of whom were in the sample set because they didn’t hear about it from my blog), the common thread is that they’re fairly somatically aware, but didn’t start that way. I’m not sure how important that second part is: I don’t know anyone who is just naturally embodied. It seems possible that somatic awareness is either necessary to benefit from the Apollo, or necessary to notice the effects before your motivation to fight the terrible app wears off.

Conclusion

The Apollo doesn’t work for most people, you probably shouldn’t buy it unless you’re somatically aware or have severe enough issues with sleep or anxiety that you can push through the warm-up period.

- I don’t use a formal mood tracker. But I did have a friend I ask to send me pictures of their baby when I’m stressed or sad. I stopped doing that shortly after getting the Apollo (although due to message retention issues I can’t check how long that took to kick in).

︎

If I was going to try to charitably misinterpret trevor, I'd suggest that maybe he is remembering that "the S in 'IoT' stands for Security".

(The reader stops and notices: I-O-T doesn't contain an S... yes! ...just like such devices are almost never secure.) So this particular website may have people who are centrally relevant to AI strategy, and getting them all to wear the same insecure piece of hardware lowers the cost to get a high quality attack?

So for anyone on this site who considers themselves to be an independent source of world-saving capacity with respect to AI-and-computer-stuff maybe they at least should avoid correlating with each other by trying the same weird IoT health products?

If I'm going to try to maximally predict something trevor might be saying (that isn't as charitable (and also offer my corrections and augmentations to this take))...

Maybe trevor thinks the Apollo Neuro should get FDA approval, and until that happens the device should be considered dangerous and probably not efficacious as a matter of simple category-based heuristics?

Like there's the category of "pills you find on the sidewalk" and then the question of what a "medical therapy without FDA approval" belongs in...

...and maybe that's basically "the same category" as far as trevor is suggesting?

So then trevor might just be saying "this is like that" and... I dunno... that wouldn't be at all informative to me, but maybe hearing the reasonable parts (and the unreasaonble parts) of that explanation would be informative to some readers?

(And honestly for normal people who haven't tried to write business plans in this domain or worked in a bio lab etc etc etc... this is kinda reasonable!

(It would be reasonable if there's no new communicable disease nearby. It would be reasonable if we're not talking about a vaccine or infection-killing-drug whose worst possible risk is less bad than the disease we're imminently going to be infected with due to broken port-of-entry policies and inadequate quarantines and pubic health operations in general. Like: for covid in the first wave when the mortality risk was objectively higher than now, and subjectively had large error bars due to the fog of war, deference to the FDA is not reasonable at all.))

One of the central components in my argument against the FDA is that (1) their stated goals are actually important because lots of quackery IS dangerous...

...but then part of the deeper beef with the FDA here is that (2) not even clinical government monitored trials are actually enough to detect and remove the possibility of true danger.

New drugs, fresh out of clinical trials, are less safe (because less well understood) than drugs that have been used for so long that generics exist.

With 30 year old drugs, many doctors you'll run into were taught about it in medical school, and have prescribed it over and over, and have seen patients who took the drug for 10 years without trouble and so on.

This is is just a higher level of safety. It just is.

And yet also there's no way for the inventor of a new drug with a 20-year-patent to recoup all their science costs if their science costs are very very very large...

...leading to a market sensitive definition of "orphan drugs" that a mixture of (1) broken patent law, and (2) broken medical regulation, and (3) market circumstances haphazardly emergently produce.

For example, lithium has bad long term side effects (that are often worth risking for short run patient benefits) that would never show up in a phase 2 trial. A skilled doctor doesn't care that lithium isn't "totally categorically safe" because a skilled doctor who is prescribing lithium will already know about the quirks of lithium, and be taking that into account as part of their decision to prescribe.

Just because something passed a phase 2 trial doesn't mean it is "definitely categorically safe"!

The list of withdrawn drugs in wikipedia is not complete but it shows a bunch of stuff that the FDA later officially classified as not actually "safe and effective" based on watching its use in clinical practice after approval.

That is it say, for these recalls, we can wind back to a specific phase 2 trial that generated a false positive for "safety" or a phase 3 trial that generated a false positive for "efficacy".

From my perspective (because I have a coherent mechanistic model of where medical knowledge comes from that doesn't require it to route through "peer reviewed studies" (except as a proxy for how a decent scientist might choose to distribute medical evidence they've collected from reality via careful skilled empiricism)) this isn't at all surprising!

It isn't like medicine is safe by default, and it isn't like medicine requires no skill to get right.

My core sadness is just that the FDA denies doctors professional autonomy and denies patients their body autonomy by forbidding anyone else to use their skill to make these determinations and then also the FDA gets it wrong and/or goes too slow and/or makes things way more expensive than necessary!

Like the FDA is the "king of the hill", and they're not the best at wrestling with reality... they just have a gun. They're not benevolent, they are just a bunch of careerist hacks who don't understand economics. They're not using their position to benefit the public very much in the way you'd naively expect, because they are often making decisions based on negotiations with other bureaucrats struggling to use the few levers they have, like to use FDA decisions to somehow help run medicare in a half-sane way despite the laws for medicare being broken too.

There are quicker and cheaper and more locally risk sensitive ways to try crazy medical things than the way than the centralized bureaucratic market-disrupting FDA does it from inside our generally corrupt and broken and ill-designed and sclerotic government.

Doctors in the 1950s (before the Kefauver-Harris amendment foolishly gave the FDA too much power based on an specious exuse), and those older doctors with more power and more trust made faster progress, for lower costs, than they do now.

But a lot of people (and maybe trevor?) outsource "being able to reason correctly about safety and efficacy", and so their attitude might be "down on medicine in general" or "down on even-slightly-shady health products in general" or something?

And if a patient with a problem is bad enough at reasoning, and has no one smart and benevolent nearby to outsource their thinking to... this isn't even definitely the wrong move!

Medical knowledge is a public good.

New medical stuff is dangerous.

There should be collective social action that is funded the way public goods should be funded, to help with this important public problem!

A competent and benevolent government would be generating lots of medical knowledge in a technologically advancing utopia... just not by using a broad "default ban" on medical innovation.

(A sanely built government would have something instead of the FDA, but that thing wouldn't work the way the FDA currently works, with efficient medical innovation de facto forbidden, the Right To Try de facto abolished, and doctors and smart people losing even the legal right to talk to each other about some options, and everyone else losing the right to honestly buy and honestly sell any medical thing in a way that involves them honestly talking about its operation and intended uses.)

I don't know how much of this trevor was saying.

He invoked "categorical classification of medicine" without really explaining that the categories are subjective and contingent and nominal and socially constructed by a more-than-half-broken socio-political process that economists regularly bemoan for being broken.

I think, Elizabeth, that you're trying to detect local detailed risk models specific to the "Apollo Neuro" that might risk the safety of the user as a health intervention.

This this regard, I have very little detailed local knowledge and no coherent posterior beliefs about the Apollo Neuro specifically... and my hunch is that trevor doesn't either?