I don’t know if you’ve ever had the experience of hiking in the wilderness with a map and compass but no cell service. I recommend it, if you haven’t.

I somehow did not quite all-the-way understand what a map even is until I was lost on my own under these circumstances. I knew in a “factual knowledge” sense that maps were drawings of the land, and I’d even used them as a kid and teenager to help my family navigate on road trips. But when I was lost in a national park, trying to find my way back to my car, I confronted the incompleteness of my knowledge of maps. There was a shift.

My map had trail lines drawn on it, with labels like “Canyon Trail”. I’d pause my walking to look at the shape of “Canyon Trail”, noting that it intersected "Overlook Trail" somewhere off to the left of where I was standing. Then I would walk again—attempting, I think, to "follow Canyon Trail to Overlook Trail".

I would move back and forth between walking and map consultation, making sure I remembered which way the trails were supposed to go, constantly placing and replacing myself within the borders of the lines drawn on the paper. The more distressed I felt about being lost, the more often I turned to the map, looking for something to hold on to.

The shift happened after… (this is sort of embarrassing, it’s so simple. But it’s true.) The shift happened after, having oriented myself toward “North”, I happened to lower the map a little bit, probably out of exhaustion. I held it a bit below eye level, so that it was no longer taking up my whole field of vision.

I looked at the squiggly blue line on the map, and the close-together lines that I knew indicated steepness. And I saw to my left, because the map was not blocking my vision, a creek. Up ahead, I saw a steep hill.

I realized that the blue line was probably a drawing of that creek.

The contour lines were a drawing of that hill.

And then this wild rushing sensation began to wash over me. I was starting to get it. Slowly, I tilted the paper in my hands from a vertical position, partially blocking my view...

...to a horizontal position, parallel to the ground.

I held the map that way, looking out at the world the cartographer had tried to draw, and it was as though the territory rose up to meet the map, while the map spread itself across the surface of the territory. And I said to myself, “It’s a picture!”

For the first time, I understood in a practical way that a map is meant to be a top-down picture of the real world.

Before I had this realization, I wasn't behaving as though I knew myself to be in the territory, using the map as a tool. I was acting as if I were traversing the map, using my body as a kind of clunky video game controller. I had been treating the map as the terrain I "really" had to navigate.

But once I stopped playing that game, and started actually traversing the forest I was in, things went very differently. I spent most of my time looking at creeks and trees and hills, making sure I knew how the real world around me was shaped. And from that perspective, I looked down at the map to help me predict what I’d see next.

And I found my car shortly thereafter.

There are ways to increase some kinds of knowledge that largely involve staring at maps. Perhaps your own map is not clearly labeled in places, or it’s somehow inconsistent with itself, or it doesn’t match the map of an expert.

This is why it’s often valuable to clearly articulate your beliefs, even just to yourself. It’s valuable to ask yourself what you expect, and to notice when you feel confused about that. It’s valuable to ask other people what they think, or to read their books and blog posts, especially when you have reason to believe they know important things that you don’t.

But the main thing a cartographer ought to be focused on, the vast majority of the time, is the world itself.

I started studying “original seeing”, on purpose and by that name, in 2018. What stood out to me about my earliest exploratory experiments in original seeing is how alien the world is.

I don’t mean that reality is weird or surprising. Nothing weird has ever happened, and all of that. What I mean is… well, I think I should actually grab an Eliezer quote here:

Human intuitions were produced by evolution and evolution is a hack. The same optimization process that built your retina backward and then routed the optic cable through your field of vision, also designed your visual system to process persistent objects bouncing around in 3 spatial dimensions because that's what it took to chase down tigers. But "tigers" are leaky surface generalizations - tigers came into existence gradually over evolutionary time, and they are not all absolutely similar to each other. When you go down to the fundamental level, the level on which the laws are stable, global, and exception-free, there aren't any tigers. In fact there aren't any persistent objects bouncing around in 3 spatial dimensions.

I started my earliest experimentation with some brute-force phenomenology. I picked up an object, set it on the table in front of me, and progressively stripped away layers of perception as I observed it. It was one of these things:

I wrote, “It’s a SIM card ejection tool.”

I wrote some things about its shape and color and so forth (it was round and metal, with a pointy bit on one end); and while I noted those perceptions, I tried to name some of the interpretations my mind seemed to be engaging in as I went.

As I identified the interpretations, I deliberately loosened my grip on them: “I notice that what I perceive as ‘shadows’ needn’t be places where the object blocks rays of light; the ‘object’ could be two-dimensional, drawn on a surface with the appropriate areas shaded around it.”

I noticed that I kept thinking in terms of what the object is for, so I loosened my grip on the utility of the object, mainly by naming many other possible uses. I imagined inserting the pointy part into soil to sow tiny snapdragon seeds, etching my name on a rock, and poking an air hole in the top of a plastic container so the liquid contents will pour out more smoothly. I’ve actually ended up keeping this SIM card tool on a keychain, not so I can eject SIM trays from phones, but because it’s a great stim; I can tap it like the tip of a pencil, but without leaving dots of graphite on my finger.

I loosened my grip on several preconceptions about how the object behaves, mainly by making and testing concrete predictions, some of which turned out to be wrong. For example, I expected it to taste sharp and “metallic”, but in fact I described the flavor of the surface as “calm, cool, perhaps lightly florid”.

By the time I’d had my fill of this proto-exercise, my relationship to the object had changed substantially. I wrote:

My perceptions that seem related to the object feel very distinct from whatever is out there impinging on my senses. … I was going to simply look at a SIM card tool, and now I want to wrap my soul around this little region of reality, a region that it feels disrespectful to call a ‘SIM card tool’. Why does it feel disrespectful? Because ‘SIM card tool’ is how I use it, and my mind is trained on the distance between how I relate to my perceptions of it, and what it is.

There aren’t any tigers, and there aren’t any SIM card tools, either. It now feels… almost disgusting, to me, to lose sight of that. Disgusting like thinking of trees only as “lumber”, and cutting down entire rainforests as a result.

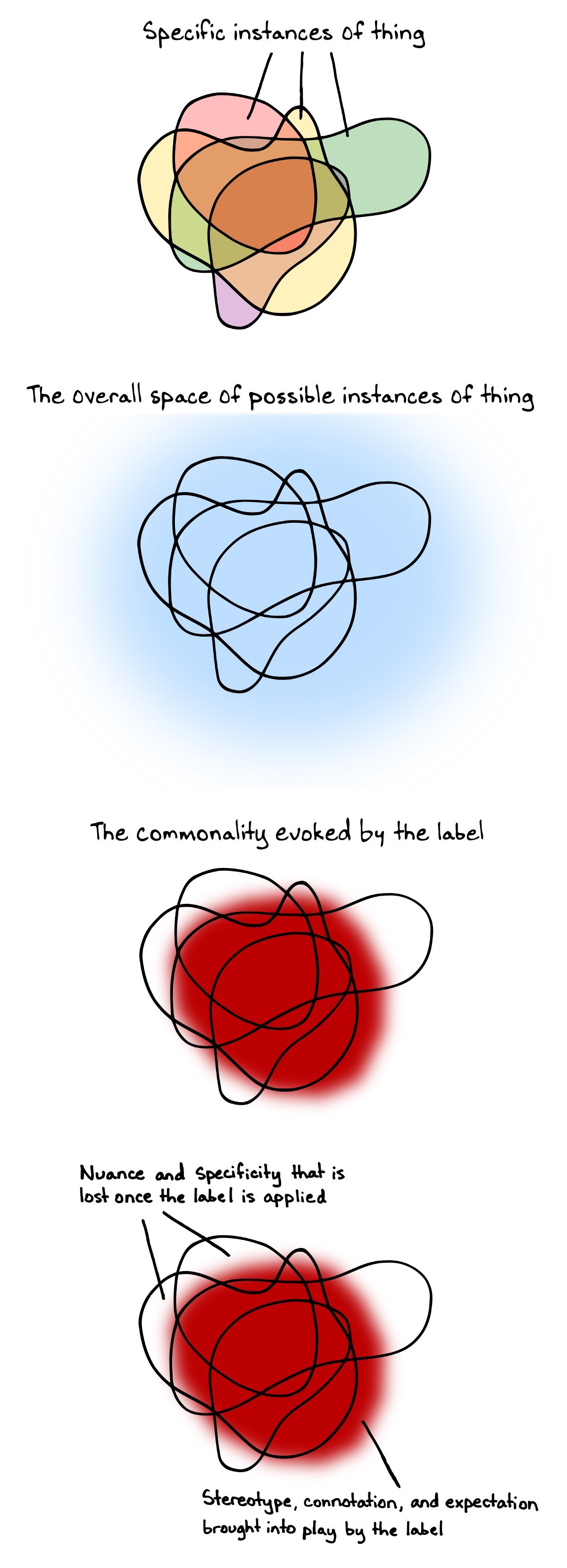

Which doesn’t mean it’s useless to conceptualize tigers and so forth. It absolutely is useful and correct. The purpose of cartography is to draw cartoon pictures that are relatively useful to travelers, and certain features of the cartoon pictures need to correspond to the real-world not-actually-”tigers” to be useful. There exist for-real regions (or properties, or patterns) of the territory itself that it makes sense to call “tigers”, as long as that concept is doing the right stuff, such as paying rent in anticipated experiences.

But ever since I began my study of original seeing—ever since observing the so-called “SIM card tool”—it has felt a little different for me to use the word “territory”.

I think that before, when I said “the territory”, I must have accidentally meant something like “the much bigger map; the thing I’m drawing a map of, which is basically like my map but a lot more complex”.

Now I mean something like, “The thing that is made of something other than my own perceptions and interpretations. The thing that resists my expectations, according to its own rules. The thing that does not care what I think, or what I have happened to imagine.”

In the sentence, “Knowing the territory takes patient and direct observation,” what I mean by “territory” is “the thing that is made of something other than my own perceptions and interpretations”.

Knowing [the thing that is made of something other than your own perceptions and interpretations] takes patient and direct observation.

Next, there will be a short interlude on realness, and what it feels like to lower the map. Then I’ll talk about observation of the territory.

This comment is about something I'm confused about, and I'm sufficiently confused about it that I can't write it as a clearly-articulated question or statement. Its current state is more like a confused question that my brain in trying to untangle as I'm reading this sequence. So I'll probably meander, and the meandering probably won't come together into a clear satisfying thing by the end of this comment.

A big reason I'm interested in Logan-style naturalism is that you (Logan) frequently say things about it that resonate with ways in which I approach my own work. The most salient instance is your concept of "pre-conceptual intimacy":

https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/EKc4RfKhPRmnLtRXn/research-facilitation-invitation

There is a particular mode that I'm in when I do what I think of as my best work, and this paragraph reminds me of it. Although, hm, now that I actually have it in front of me, most of the details don't quite match… but I think that's mostly because most of the words in this paragraph are about pre-existing concepts, and when I'm in this mode, I mostly just don't pay attention to any concepts that don't currently fit.

–I think I maybe only feel particularly disoriented when I have pre-existing concepts that don't fit, but still feel like they encapsulate something important that I don't want to lose sight of?–

Anyway, when I try to correct for these things, "pre-conceptual intimacy" seems to resonate a lot with this mode that I sometimes work in.

However, an aspect of the description above that still doesn't match is that, when I'm working in this mode, I'm not in any very obvious way making any observations. It seems like most of what I'm doing is that I'm having a vague confused intuition, and I, uh. I bump them around in my head until they maybe turn into concepts that make sense, or are at least a little more like that? (Turns out that I don't actually particularly know how to describe the thing.)

It wouldn't be incorrect, I think, to say that I'm looking at two parts of my map that are inconsistent with each other, and I'm trying to make them consistent, or I'm looking at one part of my map (my confused intuition) and I try to use it to fill in a different, blank part of my map.

This seems obviously right for literal cartography. I want to talk, as part of my meandering, about how it might apply to math. I don't actually feel confused about math, I just find it a helpful example.

It seems to me that, on the one hand, (most) math research could be described as being all about staring at some parts of your map and trying to use them to fill in other parts of your map. But–

–but on the other hand, math certainly resists my expectations according to its own rules. Moreover, when I try to do prove a math result, I am in contact with that resistance: I get feedback from the territory (of math), even though it seems like in some sense it wouldn't be incorrect to say that all I am doing is to stare at different parts of my map.

I think this is somehow an important node in my confusion (though, again, I don't actually feel confused about math): When reading your posts, I seem to have formed a, uh, story? frame?, that says that {getting feedback from the territory} is important and that it is sort of the opposite of {merely staring at your map}. So if I think of doing math as both "getting feedback from the territory" and "nothing but staring at your map", that breaks that model.

Maybe this just means that I should not think of math proofs as happening all in the map; maybe I should say that because doing math proofs gives me feedback about the way that math resists my expectations, therefore by definition it is not happening all in my map.

…I feel uncomfortable and kind of dirty about the previous paragraph, and that's after working on it for a while trying to make it less bad. As written, it seems to be saying: I have formed a picture of a constellation in my head, and now I'm looking at the sky and there is no star where my mental picture says there should be one; and I now want to know whether the real constellation instead has this nearby star or that one. Sometimes it genuinely makes sense to ask "does this way of thinking about things feel more revealing, or that one?" But in this case, it just feels like a wrong question. The real thing inside me I would like to convey is that I'm mentally lightly touching on each of the two pictures I could draw, getting in touch with how both feel somewhat right but fairly wrong, because touching on what the world looks like from these two wrong perspectives jiggers something around in my head that makes me feel that I'm a little closer to resolving my confusion.

Maybe this just means that I should not think of math proofs as happening all in the map; maybe I should say that because doing math proofs gives me feedback about the way that math resists my expectations, therefore by definition it is not happening all in my map.

But suppose I'm a physicist. I spend some of my time doing experiments, and I spend some of my time thinking about physics and about my experiments, and as I do the latter, I frequently do math. I'm not interested in studying math, the thing I want to study is physics, but math is an important tool for doing so. And when I use this tool, it resists my expectations just as it does when I do math for its own sake; once I have a formal model of some physical phenomenon, math tells me something about what to expect from my physical observations in a way that does not care what I think, or what I happened to imagine. But it feels like in the case of physics, something important is captured by saying that my experiments are making direct contact with the territory of physics, whereas the math I do is all in my map.

Worse, consider Einstein when he said that if Eddington's attempt to verify General Relativity had failed, "Then I would have felt sorry for the dear Lord. The theory is correct." [1] At this point, he had obviously done a lot of math about GR, but the math couldn't have given him that confidence that the theory was correct; given how little empirical observation [2] it was based on, it must have been {philosophical arguments slash his sense of how physics worked} that allowed him to come to this conclusion. And for him to predict so well on so little data, his philosophical intuitions must somehow have had the power to resist expectations according to their own rules, not in the way physics experiments do, but kind of close to the way mathematical calculations do. But if we tried to say that Einstein's philosophical intuitions didn't happen in the map, then… would any sort of thinking that actually does anything useful count as "happening in the map"?

[1] Each source I've checked seems to give a slightly different quote and story, which, uuuh, but anyway.

[2] (Empirical observation distinguishing it from Newtonian mechanics, I mean.)

I think that I personally have a tendency to spend a lot of time thinking about my map, and that I could, in many domains I care about, benefit from noticing a bunch of low-hanging fruit in making more direct observations. But I don't actually think that {what I consider to be my highest-quality work} to be an example of this. I mean, that work is certainly informed by intuitions I've formed in contact with present day machine-learning systems, or by doing math, or by watching my own thinking. But it's not, I think, made of contact with these things, and my contact with the territory (AGI alignment) seems to me about as tenuous as Einstein's with his. I think that the best work I do is in fact made up of thinking about what some existing parts of my map can tell me about what should be in other parts of my map.

So what am I to make of naturalism, or "Knowing the territory takes patient and direct observation"?

One story I could try to tell is that naturalism won't have much to tell me about the part of my work I consider most important. I could either say that "Knowing the territory takes patient and direct observation" is false because sometimes you can come to deep understanding of the territory just by thinking about it; or I could perhaps say that it's true, and that just thinking is useful but isn't enough to give you deep mastery of the subject; or I guess I could say that my approach to my work is just fundamentally doomed.

This story may be true. But it doesn't currently ring true, because it doesn't explain why numerous things you've said about naturalism have had such a strong resonance with my model of my work process.

When I do my thing that is in fact mostly "just thinking about it", I have a distinction in my head that I track with my felt sense, which feels as if it's tracking "whether I'm interacting with the real thing, or merely making up stories about it". In the first case, I feel like I am in contact with something that can resist my expectations (although in truth this thing is itself made of anticipations).

I very much have habits for this kind of work that rhyme with patience: I approach it with a frame of mind that "isn't expecting to find answers today", that is looking at the feeling of the thought on the tip of my tongue and pokes around in that vicinity but isn't expecting to be able to articulate that thought by any particular point in time. I look at the problem from this perspective and from that perspective, and feel successful if this shifts something in my felt sense that makes me feel a little bit less confused.

And there is an experience and sensation there that, as a felt sense, very much resonates with the idea of peeling back interpretative layers and increasing sensation at the point of contact, and with the metaphor of being "naked" in contact with the thing.

Maybe all of this is me missing you and interpreting your words in terms of something I'm familiar with. But what I actually think is going on is that your words are painting a picture of a constellation in my head that sort-of-but-not-quite matches the stars I see in the night sky; and that there is some nearby picture that does make sense of what I'm seeing; but I, like, just really don't know what that picture looks like, yet. (And so I look at it from this wrong perspective and from that one, and notice how that shifts my felt sense of it a little and makes me feel a little less confused–which is why I had to write a long meandering semi-essay in order to be able to say anything detailed about it at all.)

I think somewhere in that comment I meant to link to my essay on primitive introspection, but never got around to it. I think I meant to say something about how the most useful sense organ for receiving data about math, whatever that is, is the prefrontal cortex, and the reason naturalism stuff keeps resonating with you is because naturalism is largely about improving your PFC-qua-sense-organ the same way a novice perfumer is in the process of improving their nose-qua-sense-organ. Maybe.