Happy to see activity toward this. I agree that, for some targets at least, cash transfers are likely more effective than targeted services or programs. I don't agree that this is true for all impoverished persons, and I don't understand how to tell the difference at scale.

Part of my confusion/disagreement is that these tend to get framed as populations, rather than individuals, but the pilot programs are about a small number of individuals. There seems to be no recognition that individuals come and go from populations, and there's a ton of overlap/leakage between a served and an unserved population for any given program. IMO, very small pilots are often successful not because of the underlying mechanisms, but because of observation and selection effects.

Thanks for the comment! I also do not think cash will be more effective for - every - impoverished person. I do think, however, that most are a lot closer to almost all with the only exceptions being people that are suffering from extreme drug addiction and/or mental illness. Actually, there's some spotty evidence (we need a good RTC study on this) that cash transfers could actually be a cost-effective way to reduce drug usage. (check out Simon, a case study who was a 20-year homeless heroin addict).

individuals come and go from populations, and there's a ton of overlap/leakage between a served and an unserved population for any given program

I 100% agree with your comment that we should make sure to look at the individuals as well as the larger data. I may be misunderstanding your point, but I think you might be misunderstanding how guaranteed income programs work. Some are household-based, but I vastly prefer individual-based (it means larger families get more support and individuals are empowered to, for example, escape abusive relationships).

Either way, the individuals or households in the population selected do not leak between served and unserved during the duration of their transfers. The whole point of guaranteed income is its consistency for every person in the program.

very small pilots are often successful not because of the underlying mechanisms, but because of observation and selection effects

This is an argument I see pretty frequently, and I agree that (specifically for homeless people) more research is needed. That said, in the largest GI Randomized Controlled Trial experiment for homeless people, the (115) pilot participants were not carefully overseen. "Participants completed questionnaires at 1 month and then every 3 months. To better understand individual experiences, participants also completed open-ended qualitative interviews after 6 and 12 months."

Nonetheless, spending on drugs & alcohol went down by 39%, and the pilot was a massive success. It appears like larger, better pilots with fewer observation and selection biases don't have worse results than the small ones.

I have serious concerns about the study designs. Firstly, everything is based on surveys. Saying to someone (implicitly) "I am giving you free money to do less drugs. Now, how much less drugs are you doing?" lacks rigor in a fundamental sense. There needs to be objective follow-up metrics with things like emergency room visits and incarceration rates.

"Nonetheless, spending on drugs & alcohol went down by 39%, and the pilot was a massive success."

According to surveys given to the participants. Even if you tell them that the payments aren't contingent on positive results, they don't necessarily believe you. And even if they do, they'll still feel obliged to give you the results you're after. This is a commonly known effect in psychology and sociology, but it was never addressed.

Secondly, there are no comparisons with other programs, like directly providing housing. What exactly is the relative benefit of direct cash transfers over conventional welfare programs like food stamps? Less overhead? It seems marginal at best.

Thirdly, most of your links are to your own foundation, and you're explicitly here to ask for money. Everything is optimized to make your hypothesis look good without a counterargument. You understand how this looks.

First, thank you for your rigor in analyzing the homelessness part of the post! I most certainly agree with you that cash transfers - explicitly relating to homeless individuals - need more studies and more rigorous RTCs from independent sources.

According to surveys given to the participants. Even if you tell them that the payments aren't contingent on positive results, they don't necessarily believe you. And even if they do, they'll still feel obliged to give you the results you're after. This is a commonly known effect in psychology and sociology, but it was never addressed.

Thanks for pointing this out, I completely agree. I'll add this to the document as an important disclaimer.

That said, I also want to add a modifier talking about how the general public is also full of drug users (have you had beer/wine/cannabis in the last year?) and we don't judge them at all. There's a big difference between drug use and drug addiction, and there's a very strong argument that we probably shouldn't care about drug use metrics at all. It's incarceration rates & hospital visits that we need more data on. It's also kinda impossible to accurately determine who does how many drugs without extremely invasive & expensive oversight.

Secondly, there are no comparisons with other programs, like directly providing housing. What exactly is the relative benefit of direct cash transfers over conventional welfare programs like food stamps? Less overhead? It seems marginal at best.

I did try to compare with housing first, especially about the budgets spent per 'unit'. I think that producing academic studies on these topics is essential over the next few years, I want to keep our work as falsifiable as possible.

Comparisons differ from intervention to intervention, but it comes back to the snake charts that I made right near the top.

It's not just overhead. Food stamps are pretty similar to guaranteed income because neither requires infrastructure or supply chains (like food banks do), but you still have to account for the loss caused by.

- Beneficiary Paperwork: Paperwork is usually an undignified hassle within conventional welfare programs. Wasting beneficiaries' time is costly, and hiring a ton of bureaucrats to scrutinize people is also costly.

- Inefficient Value transfer: Beneficiaries do not get exactly what they need most, so the counterfactual impact would (almost) always be larger if they had cash. I used the example below, which would probably waste ~20% of the value vs the counterfactual.

"Fundamentally, poor people are way better than nonprofit ‘experts’ at knowing what they need and getting it. For example, if someone needs a car loan and the aid program provides food stamps, they have to launder their food stamps to get the cash for their car loan. Guaranteed income empowers poor people with liquid aid."

Thirdly, most of your links are to your own foundation, and you're explicitly here to ask for money. Everything is optimized to make your hypothesis look good without a counterargument.

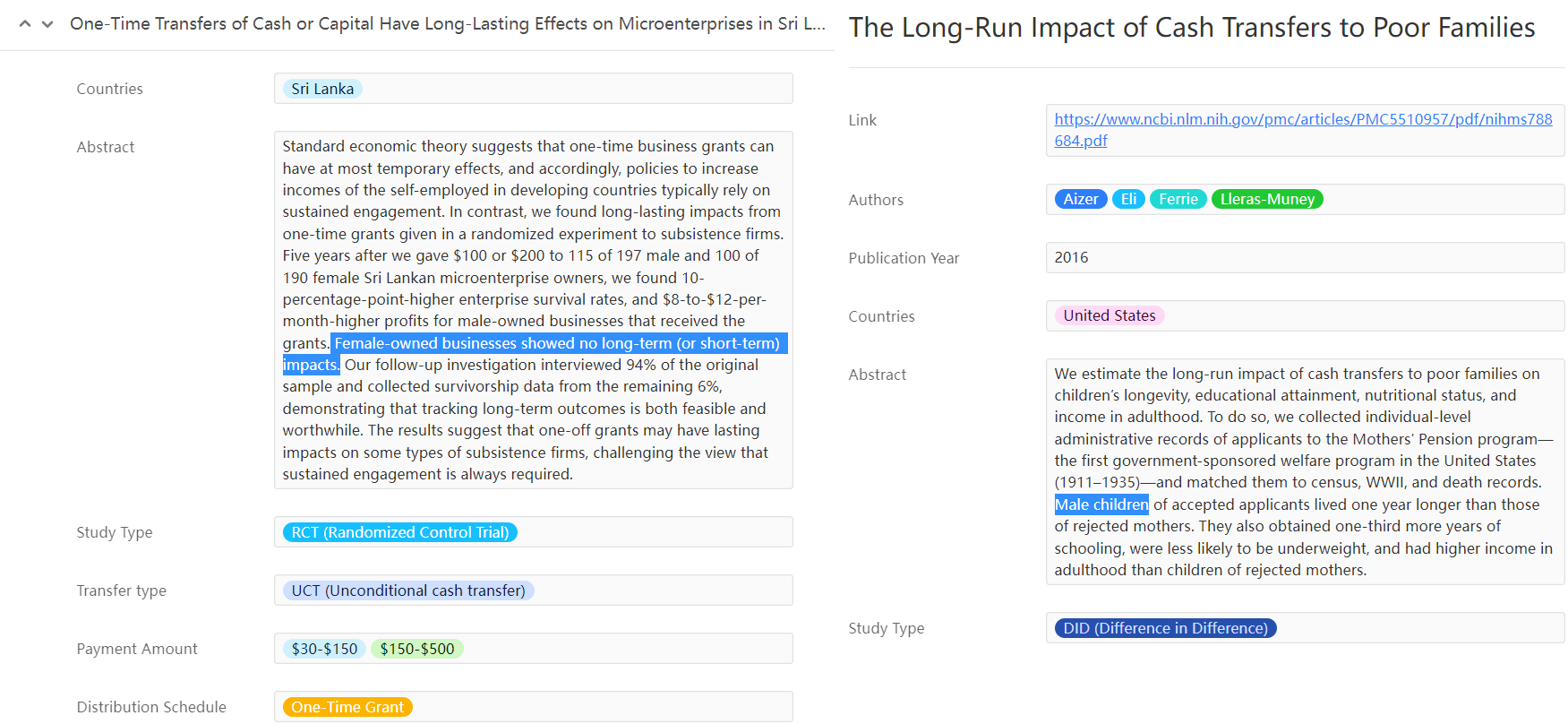

So I primarily linked to my website's research page because it has all of the links to all of the studies on it. It has a database (not curated by us) of 320+ studies, so I see your point but I'm far more interested in people accessing the research put together in one spot. For homelessness, I linked to the website because you can't click on the links in the table picture. You can click on the links, and see the source data on the website, and no one else has a list like that. I'm explicitly asking for attention -

And as for your last sentence, yes I'm looking for 3 things.

- Someone such as yourself to come up with a fundamental problem with any part of our plan (not just homelessness, as that's just a tiny part with greater risk but also reward), and save me a bunch of wasted time doing something that won't lead anywhere.

- You've hit the nail on the head, after looking at every single piece of research into "What happens when you provide guaranteed income to homeless individuals," I can't find any strong counter-arguments, other than there haven't been enough studies done yet. And considering the unparalleled research into cash transfers on other populations (global poverty, impoverished people in cities, even formerly incarcerated individuals) I'm really not optimizing the links. I'd be happy to see if you can find pretty much any strong evidence that guaranteed income isn't simply effective.

- I did state explicitly that I used a drastic underestimate for all of the impact estimates because of the lack of homelessness RTCs. Luckily there are several on the way, I'm especially looking forward to the one in Denver.

In every experiment to date, guaranteed income has helped at least 66% of participants regain economic stability. We are using an unreasonably low estimate of 50% for two reasons.

- There have only been three experiments completed as of November 2022; it’s not the biggest data set.

- Because of the logarithmic rate of the success cost curve, we could have miscalculated the optimal duration and/or the monthly amount needed. If we set the bar too high for ourselves and miss slightly, our pilot could look like a failure even if it’s extremely impactful. If only a third or quarter of participants regained housing stability, our pilot would still be an order of magnitude more cost-effective compared to other homelessness interventions

The fundemental issue of these studies is the reliance on surveys. In most of them, they are the only source of feedback! Why wasn't there any integration of objective measures like incarceration and hospital visits from the start? This isn't a minor issue - it's a flaw in the foundation.

I do not agree that hospital visits and incarceration statistics, (although I'd love to have those numbers), are foundational to measuring the impactfulness of a homeless intervention:

Overwhelming demographic data as well as medical analysis make it evident that living on the streets directly accounts for most, though not all, of the massive mortality rate increase. There is a causal relationship between living on the streets and high death rates, especially in Arizona due to the high summer heat.

I'd be happy to hear why you might disagree, but I believe it's well-established ^ that having to live on the streets directly results in almost all of the complications, hospital visits, incarceration, and other service costs that are incurred trying to keep homeless people alive. Not the other way around.

Having stable housing is by far the most important objective measure, followed in my opinion by:

- Housing Situation (the major determinant of hospitalizations & incarceration)

- Employment situation (are they going to fall back on the streets)

Under these, there are several other significant, although not foundational, metrics:

- Net Worth (how much of a cash cushion do they keep over time)

- Quality of Life

- hospitalization & incarceration metrics

- Spending Metrics

To be honest, I hadn't even thought of adding hospitalization and/or incarceration numbers until you brought them up. That said, I will add them to our pool of desired data points.

While I do see your point about surveys maybe not resulting in accurate drug usage numbers, I don't think they are all that important to the effectiveness of the intervention for the reasons I stated in the last post. They are the only subjective parts of these surveys that might be skewed due to cognitive bias.

The only feedback you are getting is from surveys. They are subjective by definition. Gifts provide immense psychological pressure for reciprocation, especially if it's presented as "no-strings-attached". Every metric you cite improvement in is subject to this. This is why I'm so troubled by the lack of objective metrics or any other attempt to mitigate this. The fact that this isn't addressed is a major red flag. Do you have any statisticians associated with the project to help with study design?

Let me give an analogy. Let's say you dropped out of college and play video games all day. Your parents call in on the weekends and ask you about your job search and how much video games you're playing. Do you think you're more likely to lie or exagerate about your achievements if they're paying your rent? Even if you knew for sure they weren't going to pull finiancial support regardless? And what if this continued over the course of months?

I will write up an article some time this week regarding all this.

Our organization is not big enough to hire a statistician, although we will for sure get one when we are able to build a sufficiently large study / program. I'd be happy to refer you to the people that do have a ton of statisticians:

https://www.givedirectly.org/research-at-give-directly/

https://basicincome.stanford.edu/research/ubi-visualization/

https://www.penncgir.org/research

Let's use a different analogy. Let's say that you are in exactly the same situation you are in right now, and some random organization decided to start giving you $1,000 checks every month for one year. All they want, is periodic updates on how you're doing, and they tell you that your answers are anonymized and will not affect the payments. Would you go out of your way to lie to them?

We are not trying to be anyone's parents, and have no desire for the weird inter-personal shame dynamics that would be going on in your analogy.

Let me consolidate my criticism of this into a single post.

Surveys alone don't prove anything

The complete reliance on surveys make it impossible to distinguish between the null hypothesis and the novel hypothesis. Based on the information available, we have no way to tell if it's actually working, and if so, by how much. The experimenter effect can be big, and in this case it's probably massive. People feel a sense of obligation whenever they recieve gifts, especially if there is "no strings attached". The typical example used here are Hare Krishnas giving people flowers to solicit donations at airports. It is reasonable to expect that giving people life-changing amounts of money is enough to elicit a sense of obligation.

Experimental subjects, like most people, are quite nice. They want the nice people who gave them money to succeed. They want you to get the experimental results you're looking for. So either unconsciously or consciously, this will bias survey results. I mean, when I was looking for a job after college on my parents' money, I absolutely reported more progress than actually took place. "Of course I sent all 5 applications this week, don't worry about it, haha. What? No, of course I'm not playing video games all day." And that's just to avoid social awkwardness.

As they are designed, there is no way to distinguish between this and the actual improvement in life outcomes you are looking for. You need to examine objective measures. There is no way around this. And I know what you're thinking, "but it definitely improves housing, which reduces deaths in Arizona!" But where are you getting that idea from? Your priors? And if you knew that already, why are you even running the experiment?

There is a reason why medical testing can't rely on patient feedback alone. Because otherwise amphetamines look like a cure-all that makes everything better (aka the early 20th century).

The dog that didn't bark - no comparisons with conventional interventions

The bar isn't that it needs to be better than no intervention - it needs to be so much better than conventional interventions that it justifies the switching costs. People have been enthusiastic about direct cash payments for decades. The fact that there aren't decisively positive head-to-head comparisons against conventional programs is damning. If people have invested millions of dollars into trying to promote drug X and published dozens of papers, and there are none comparing it with its competitor drug Y, there is an implication. The implication is that drug X isn't significantly more effective than drug Y. A direct comparison isn't a "nice to have" part of a study. It is critical for it to be of any use.

Studies in support: elderly hispanic women effect

Some of the studies listed in support look p-hacked.

It's not decisive, since even true theories will have weak evidence, but it's not a good look.

Conclusion:

This isn't a little bad - I would go so far as to say that without massive revisions on study design, any further investment will be literally scientifically useless. It doesn't matter how many more projects you do. The foundation is flawed.

I seriously considered not writing this, since dunking on charities makes me look bad, but it honestly looks like whoever designed these studies didn't have a solid understanding of experiment design. These problems jumped out to me immediately when I read your post and started digging. Not 1 hour after, not 10 minutes after, immediately. Whoever designed them should know better.

Edit: toned down rhetoic slightly

Good thing I'm not particularly interested in being a charity, I'm interested in building a tool for funders and fundraisers that maximizes their impact against poverty. So bring on the criticism.

That said, I think you're being excessively negative towards surveys in general. There are two primary reason why surveys are (seemingly) the only way to go about getting decent data, and not nearly as unreliable as you're suggesting.

- I can't think of another way to go about collecting more accurate & less biased information. The only way 100% know exactly what even one person is spending their money on and doing every day is to have a researcher follow them around, watch exactly what they do, and record every change in their life over 6 months. Doing that would likely result in way bigger behavior changes than any survay ever would. It would also be expensive, extraordinarily undignified. Can you think of a single way to actually go about getting the detailed factual information that would not cause far larger behavior changes or be horrifically undignified (like a tiny bug drone that flies around watching people, and inviting lawsuits)?

- While people may feel an obligation to give good answers about drug use, for example, funding has not been determinant on the answers to the questions. Why would anyone go out of their way to lie about an easily checkable questions like: Where are you living at? Do you have a job? Or what is your net worth? People have no incentive to missstate answers to those questions.

It's also important to not that it is not just survays. The New Leaf Project survay, and many of GiveDirectly's research includes in-person interviews. Interviews that often take place in the homes that participants have attained because of the program. I've never seen a single example of a random in-person check-in discovering that a participant is actually still homeless, having lied about attaining a stable place to live.

With regards to the database, that is all of the research out there across all time with anything to do with cash transfers. I cannot say that guaranteed income is 100% proven against homelessness because there are only a handful of studies on that. Simmilarly, you should know better than to pick out two random studies. We should both be relying on the big studies looking into tons of other studies, like the one from this graph: Graph adapted from Bastagli, Zanker, et al (2016)

In conclusion

It seems to me that you have created a completely unfalsifiable position that survay recipients will systematically misrepresent their ideas. This isn't an argument about guaranteed income (correct me if I'm misunderstanding ofc), it seems to be suggesting that all survays, especially those where participants have been helped in any way, are fundamentally unreliable because participants are inherently untrustworthy. Any study to analyze this argument would inevitably cause greater misrepresentations compared to the counterfactual.

Finally, and I actually very much enjoy the discourse, but insight can be gained by looking from a rational angle as well as research-based. What would you do if given a guaranteed income ($1,000 a month for a year)? Would you randomly start reporting demonstrable falsehoods to researchers on survays even if there was no reason to? If not, why assume that many (if not most) other participants would?

You're the one with the novel hypothesis here. The burden of proof is on you. And I am rightfully suspicious of survey results and believe survey-only studies are of almost no use. Why?

Because self-report is fundamentally unreliable. Yes, I am absolutely saying that people who receive money from you are incentivized to lie to you out of a sense of social obligation. Yes, I am saying that this means any study where you provide help and then rely on self-report as the only form of feedback is borderline useless and will convince few people. And no, it's not an unfalsifiable idea - objective metrics can be used as a comparison. If it is impossible to collect such data ethically, then you should stop doing your studies immediately. If your best piece of evidence in support of your ideas is just "think about it logically", I would highly recommend that EA charities never fund this project.

While people may feel an obligation to give good answers about drug use, for example, funding has not been determinant on the answers to the questions. Why would anyone go out of their way to lie about an easily checkable questions like: Where are you living at? Do you have a job? Or what is your net worth? People have no incentive to missstate answers to those questions.

To avoid embarrassment and awkwardness. To make the researchers feel better. This is a well-known problem in psychology called the "self-report bias", which is why good psychological studies never rely on self-report alone. As verification, you can also interview other family members, and employers, check arrest records, ect. If there is no way for you to do this ethically, then what do you think your studies are achieving?

I've never seen a single example of a random in-person check-in discovering that a participant is actually still homeless, having lied about attaining a stable place to live.

You ask someone if it's OK for you to drop by at their place sometime, and for their address. This is verifiable information, and they aren't likely to lie to you. If you ask them about things they know you can't check, they are much more likely to make a socially desirable lie. They know you can't check how much money they're spending on drugs, or if they're employed. People even lie to themselves about how much they exercise all the time. I'm not sure what your position here is. That people don't make prosocial lies out of a sense of obligation? People lie about how good each others' cooking is to avoid hurt feelings. Most explanations of the self-report bias effect start with the most important one: Subjects may make the more socially acceptable answer rather than being truthful. This needs to be addressed. If you were ever wondering why people aren't donating more money to direct cash transfers, this is reason #1.

There is also the problem of reporting bias and problems with subject follow-up. The people who went to jail/hospital/mental hospital/morgue are a lot less likely to be reporting back. Same with the ones who deteriorate mentally. You need to be accounting for all these problems. In order to get people to take direct cash transfers seriously, you need to do a head-to-head comparison with traditional interventions (housing, food stamps), and with objective measurements (days of school attended, arrest record). I don't recall this being addressed in the studies I've examined, but I haven't been able to go through many of them.

I can't think of another way to go about collecting more accurate & less biased information.

This is lethal. EA is fundamentally about evidence-based charity. You're telling us that you can't get more objective data, and that the best we can get is self-report survey data. And then you ask for money anyways.

I'm not going to pretend to be OK with this. This is not OK. This is upsetting. This is using bad statistics to get charity money. I'm not going to go so far as to suggest you're doing this intentionally, but you NEED A STATISTICIAN. A good one. Maybe it's true that you can't afford one, but you also can't afford to not have one.

Here's a review paper of how alcoholism recovery studies inflate their success rates. I notice a disturbing overlap with your practices.

We need to take a bit of a step back here. I am just as keen as you are to get good unbiased data that can be relied upon to know precisely how impactful cash transfers - and other interventions - are at helping people. And I'd like to acknowledge that you're correct that we should not rely solely on unchecked survey data when trying to figure out impact results.

So I did a bit of a deep dive into meta-analyses and systematic reviews of cash transfer studies. It turns out that while surveys are generally one part of the data collected, researchers have been able to use objective measures and collect data that participants can't lie about (such as government income reporting, and school attendance rates among others). So I figure you might find it useful to check out the systematic reviews, and the organizations with tons of statisticians that have likely accounted for the very real problems you've pointed out with surveys.

We all know GiveWell, they do extremely rigorous analyses of studies, and came to this conclusion:

Their focus is primarily on cash transfers in developing nations, but I think their point about non-health interventions is especially interesting when considering how effective health interventions are much harder to come by in developed nations. There are several research institutions entirely dedicated to sussing out the effectiveness of cash transfers. They have tons of statisticians, and I'm sure they actively account for the issues with surveys versus other data types.

https://as.nyu.edu/departments/cash-transfer-lab/faq.html

https://basicincome.stanford.edu/research/ubi-visualization/

https://www.penncgir.org/research

I would like to see more research comparing cash directly to other interventions, I think there are a surprisingly large amount of current interventions going on that are either marginally helpful or actively harmful to beneficiaries. The most important thing in philanthropy is diverting as much funding as possible, at a global scale, to the interventions that we know are the most highly effective.

You've mentioned a few times that I need a statistician for what we're doing, and I fully intend on going even further. When we have a large enough experiment to run we will not only hire a statistician but have unbiased external scientific institutions operate the research alongside our program (such as the research labs linked above). That way we cannot manipulate their results. I am very interested in falsifiable studies that can either indicate we're going in the right direction or prevent us from wasting a lot of time on something that isn't impactful.

Finally, I'm well aware that guaranteed income regarding homelessness is far smaller and much less rigorous than cash transfers in general or globally. However we've spoken to dozens of homeless aid workers as well as homeless people, and we've seen promising anecdotal results from all of the (imperfect) small to medium-scale studies done so far. As long as we're conducting good large-scale research, and (good of you to point out) not relying entirely on surveys or other potentially biased metrics, I think doing larger-scale and higher-quality research is well worth EA dollars.

If the larger studies prove what we think we see happening on a small scale, we could solve the homelessness crisis with ~10% of the current amount we spend on the problem. If the large-scale studies show less impact, but are still in the same range as general cash transfer research, then guaranteed income would still be the most cost-effective way to help the homeless, just not 5-10X better than the other methods as it currently looks.

Overall, better research is needed, and we fully intend to produce highly consequential studies once we have the funding to launch a statistically relevant program. If we could get an EA statistician to look over the current homelessness research, they would be far more qualified than you or I to know just how much trust we should be putting in the research done so far. Do you know any?

Hmm, it's a good idea in theory, but in reality to be successful one would need to guarantee UBI to everyone, without means testing, for credibly unlimited duration, linked to a reasonable index to protect against inflation. This is very expensive, even if restricted to the amount where one can survive on it in cheaper areas. The US seems like a poor testing ground for it. Some small European country might be a better start.

to be successful one would need to guarantee UBI to everyone, without means testing, for credibly unlimited duration, linked to a reasonable index to protect against inflation.

I would like to see a reason stated for any of these assertions. We're not doing UBI, or unlimited durations (at first at least). We also will be forced to do some means testing because of IRS limitations on 501(c)(3)s, but it will be only a 30-minute application. Our initial experiments will not be indexed to inflation because we still need to figure out the optimal amount to help people.

What do you mean by expensive? It seems clear we're currently spending a lot more money a lot less impactfully. Our Pilot Budget is $182,000.

The US seems like a poor testing ground for it.

The second half of the post describes in detail why Arizona & homelessness is likely the highest-impact opportunity anywhere in the developed world. I'd like to hear the reasoning.

Hmm, you are certainly infinitely more familiar with the topic. I basically followed Scott Alexander's blog posts about UBI which is not what you are trying to do here. I agree that giving money directly makes more sense than most alternatives. I am guessing that there is a subset of the population for whom it will work, and won't just go into, say, drugs and gambling without a noticeable change in quality of life or mortality, but identifying it might be tricky, so you have to accept that a fair amount of money does not do any good. There was a local experiment with a one-time transfer that had some positive results https://forsocialchange.org/new-leaf-project-overview but the homeless situation here is getting progressively worse still.

So we've got two major types of guaranteed income experiments, those on homeless individuals, and those on the general (impoverished) public.

I agree with you that the New Leaf Project experiment (that I cited quite a bit) was quite positive, and also that the problem is still getting worse. Although It's important to note that that experiment only had 115 participants, so it covered only a drop in the bucket.

The real question is, "If guaranteed income was scaled up to cover the entire population in homelessness or in danger of becoming homeless, would the results of the experiment stay true?". Would it eradicate (mostly at least) homelessness? This has never been done so far, but considering the evidence, it seems to at least be worth trying. Especially because guaranteed income is way less expensive than all other forms of assistance. We spend ~$80,000 on average servicing each homeless person, giving them even $1,000 a month, which is <1/5 the cost. And it looks so far to be substantially more effective.

I am guessing that there is a subset of the population for whom it will work, verkeepingrsus keep neutral or potentially harm.

The important question, as you accurately point out, is, " How big is that subset of society".

Luckily, this is the part where there is infinitely more research and data available, including large-scale experiments to look at. There's a map with dozens of studies, the results of a large random experiment in Stockton California, and the results from the most comprehensive UBI experiment ever.

If anything, please watch this 15-minute TED Talk. I think you'll find it fascinating.

guaranteed income is way less expensive than all other forms of assistance

Is it intended as a substitute for other forms of assistance?

I think at first, definitely not. I see it playing out like this:

- While other forms of assistance are going about things like normal, someone (us) builds a big enough guaranteed income program to provide half or most of the homeless population in an area with guaranteed income.

- When that program happens, hopefully, most homeless people attain far better situations within a year, and the existing assistance services find themselves with more resources available to assist fewer people (the ones in highly bad mental states/addiction).

- Using guaranteed income to help people in danger of falling into homelessness drastically reduces the rates of people falling into homelessness, and leaves the existing service providers with less and less to do over time, twiddling their thumbs.

- Peace and quiet.

- Only then, will funding slowly get transitioned to guaranteed income (not all, some 20-30% will probably still be needed for intensive addiction, psychiatric services, and disaster relief). At this point, there will probably need to be major policy changes.

Is that ambitious, yeah, but it all relies on #2. Somebody needs to try it.

Thanks for reading this 30-minute thing. I first wanted to make a short 5-minute read but I realized that many of you would probably really want all of the evidence laid out clearly, and our plan explained in excruciating detail. - so you can point out the super obvious reason why this has a 0% chance of success, that I've completely overlooked - despite my search for fundamental issues since I came up with the idea, and asking all of the experts I can find.

The EA community is probably the most knowledgeable community in the world about helping people. Considering the world-changing impact potential I've outlined, even a 1% chance of success would justify spending millions to make this happen. Unless of course, someone can find a problem.

Please find a fundamental, first-principles problem with my plan, and, if you can't, please help us succeed. My challenge for you: Find an insurmountable problem, or help us change the world.

I think our odds are more like 40% without support from EA organizations and as high as 75% with your support. The faster we can grow (but not too fast), the faster we may be able to end poverty. Time is very much of the essence.

It would change power dynamics, enabling victims to escape abusive relationships and workers to escape exploitative jobs.

Reducing poverty at a large scale would free millions of poor people to do things other than work to survive day-to-day (such as seek out impactful careers)

If money remains a thing and capitalism continues to be the most efficient system for getting everyone everything they want, then guaranteed income should be one of the fundamental positives in the long-term future of humanity.

Taking out at scale the most extractive labour globally will both do a lot of good and draw the ire of the most aggressive economic players. Making a chair taller by chopping of a leg for building materials is not a repeatable strategy. One may not like what is going on in the kitchen, but serving unprocessed ingredients will improve nutrition and will drive down patreonage.

First, I realized that while GiveDirectly could build the platform, it might go against their #1 value of "putting the poor in control of how aid money is spent". If we want to maximize funders, we have to work within their bounds

If the disruption enabled by guaranteed income is inevitable. Our impact could therefore be accelerating the disruption while ensuring that guaranteed income isn’t used for negative purposes. Dictatorial governments could, for example, tie social credit scores to the amount of a basic income, entrenching the undeserving poor myth. This could be an extremely powerful tool in the wrong hands to entrench social stratification.

So, you are making a place for givers to choose their beggars and are then worried about partiality.

Overall, I guess a post office is more "efficient" than a factory but a factory produces something that did not exist otherwise. There seems to be no reason why fundraisers working within the platform instead of outside of it would be more efficient to make people give more. For the logistics, I don't see what service is being provided for the help direction. Sure, using a develped country means that whatever personal need the receipient has there is a specialised industry to serve that. And for undeveloped countries an existing industry is proven to be viable and possible instead of illfitted outside injection. But money used in undeveloped country will suffer from the local infrastructure not being, well, developed. Using a definition of dollars for value creates a big distortion there. Sure, if I need car in developed country and pay $1000 for it and pay in undeveloped country £3000 in one sense both are "100% money to need fulfillment". But on another view the other option is three times less efficient. Providing a $2000 car in the poor area is in one view half as efficient as a rich area car but on another view significantly more efficient than the local poor infrastructure option.

Starting out local and using a distinguishing factor of "we plan to go global" mainly just means you are trying to bite a too big of a chunk to chew. My points go to the grounded activity. Let's factor in theather size once it is at hand instead of a cloud castle.

This potential future excites me, and I’d like to see what other longtermist effective altruists think about it. The likelihood of this? Also not zero.

Yeah, hello Pascal's mugger. It was atleast interesting when there were numbers about the amount of rooms in the castle making up the deficiencies in building materials. In the wake of FTX big payouts on tail probabilities might be a bit of a challenging sell.

Taking out at scale the most extractive labour globally will both do a lot of good and draw the ire of the most aggressive economic players. Making a chair taller by chopping of a leg for building materials is not a repeatable strategy. One may not like what is going on in the kitchen, but serving unprocessed ingredients will improve nutrition and will drive down patreonage.

I think I'm missing your point. UBI is a long way off, but there are a lot of (mostly economic theory) writings about how guaranteed income at a large scale would drastically shift power in our economy/society in a positive way for people across the wealth spectrum. It might draw ire, but It's totally worth doing. I just hope we don't get assassinated

For the logistics, I don't see what service is being provided for the help direction. Sure, using a develped country means that whatever personal need the receipient has there is a specialised industry to serve that. And for undeveloped countries an existing industry is proven to be viable and possible instead of illfitted outside injection. But money used in undeveloped country will suffer from the local infrastructure not being, well, developed. Using a definition of dollars for value creates a big distortion there. Sure, if I need car in developed country and pay $1000 for it and pay in undeveloped country £3000 in one sense both are "100% money to need fulfillment". But on another view the other option is three times less efficient. Providing a $2000 car in the poor area is in one view half as efficient as a rich area car but on another view significantly more efficient than the local poor infrastructure option.

I think it could be important to take a look at the many examples of people in developed nations sending stuff to developing countries that they don't actually need, or want, the most. A car might be cheaper to deliver than a local car would be to buy, but most of the lime locals are not looking to buy a car, they need something else that is specific to them or their village. You have to be comparing the counterfactual value gained by beneficiaries if they were given $2,000 versus the $2,000 cost (including all logistical and administrative costs) of delivering a certain item such as a car.

I also can't think of any other metric than dollars, and it does account for examples wherien not giving people money could be more efficient. A case point would be GiveWell's Top Charities, they don't give cash 'value' but instead, they give cheap, easily distributable items that have incredibly large life-saving impact 'value'. Money value, lives saved value, economic multiplier effects value... all of these things can be most easily converted to dollars for comparison - although none of this is easy at all.

Yeah, hello Pascal's mugger. It was atleast interesting when there were numbers about the amount of rooms in the castle making up the deficiencies in building materials. In the wake of FTX big payouts on tail probabilities might be a bit of a challenging sell.

Hi Pascal! But in all seriousness, I don't think that there's a near-zero chance. Given the research, I've outlined, and the input that I've received from a bunch of unbiased professionals in the nonprofit industry, I think the likelihood is closer to 40% if we do not get any support from EA, and over 75% if we do get tons of support. Unlike FTX's BSBF I'm not interested in a microscopic chance of massive impact, I'm interested in a likely chance of massive, within a decade, impact. The comment was basically meant to ask," How low would the likelihood of these impacts happening have to be before not dropping everything and working hard on this problem would not be worth it". Perhaps an unhelpful question.

What I'm looking for is people like you to please find a fundamental first-principles problem with the plan.

You're right I probably should make our actual chances clearer though. I don't want to argue about 0-1% chance, I'd like people to argue that our chances are not 40%, but 0 instead.

I think I'm missing your point. UBI is a long way off, but there are a lot of (mostly economic theory) writings about how guaranteed income at a large scale would drastically shift power in our economy/society in a positive way for people across the wealth spectrum. It might draw ire, but It's totally worth doing. I just hope we don't get assassinated

Those people are trying to persuade the whole public at first and then moving. With this apporoach we first move and then show it was a good thing. Sure need to get funders on board but private money pushing ahead of public policy is a "shoot first, ask permission later" approach.

Climate change people need to deal with misinformation and mudding of the waters by oil companies and such. It is not just that the public randomly happens to be ignorant and a simple informing will do the trick. There is a lot of PR done by neoliberalism and such which will reactively up its efforts when the boat starts to shake. The pipedreams talk about the future but the grassroots squashing is done today.

Western intelligence agencies, atleast for the bad apples part, will topple foreign orders if the environment is not sufficiently corporation-friendly. If the issues become hot, freedom of operation or experimentation might not be there. And here scale matters, a political wind that 1% of the population is symphatetic to can be tolerated. So lifting individual people up does not pose a threat to the way of life. But doing that to whole classes of people does more than just the sum of the individual cases. Sure more things become possible but pushing an old system aside means everybody invested in the old way will have their survival instincts triggered. You don't want to be on the business end of capitalism defending itself. So knowing which structures are (felt) existentially central is key to letting sleeping bears lay.

Say you have a 20 M program running in a country. Yay, people are free to self-improve. But it also means they are not doing their previous income activity. Will there be a search for all those task that these people were doing? Probably. And because they were the bottom 20 M the replacements will not do it for cheaper (this is somewhat unique condition for this setup (normal economic thinking assumes that others step up)). Sure some tasks are not worth the new cost and the increased demands might not be that much. But the switchers will reduce laborers for the next wage class (and this recourses as much as it needs to). Doing it at scale means firms feel the statistical impact. Or is the bid that they could full-time self-improve but will statistically significantly choose not to? If you did a wholesale reform at once you can jump to a new balance point. But doing it gradually within existing dynamics means that the hunger for labour will growl.

Those people are trying to persuade the whole public at first and then moving. With this apporoach we first move and then show it was a good thing. Sure need to get funders on board but private money pushing ahead of public policy is a "shoot first, ask permission later" approach.

You're pretty much right. I started my journey writing about UBI policy and its potential to improve society, but I got fed up with politics. I do think the danger isn't quite as bad at first. We basically have permission to 'shoot' because guaranteed income pilots are very common nowadays and tons of cities and private organizations have launched guaranteed income pilots. We will have to ensure that our platform cannot violate IRS rules about who qualifies as 'in need'.

Sure more things become possible but pushing an old system aside means everybody invested in the old way will have their survival instincts triggered. You don't want to be on the business end of capitalism defending itself. So knowing which structures are (felt) existentially central is key to letting sleeping bears lay.

So basically, watch our backs when we get big enough for entrenched interests to start losing their grip on exploited labor. That's a good piece of advice, although, I think we may be able to get wealthy & powerful people to at least claim to support guaranteed income. I think it will be important for us to leave the more political side of it all to other organizations such as Income Movement and the Economic Security Project

With messaging, I see it as framing guaranteed income as the most powerful possible way to help almost any group of people in any location, and back that up with tons of falsifiable research. It'll be pretty tough to attack us I think. At the same time, lots of technologists and powerful people think that guaranteed income is the only thing that can save capitalism and ensure prosperity during a time of automation.

A 20 M program would fund only 3K participants for 1 year at $500 a month. For perspective, there are 13.5K people homeless in Arizona.

And 13.5K people are approximately 0.02% of the population in Arizona. We would have to be throwing around billions (and that is the goal between 5-10 years) to make any noticeable macroeconomic impacts on the labor force.

Say you have a 20 M program running in a country. Yay, people are free to self-improve. But it also means they are not doing their previous income activity. Will there be a search for all those task that these people were doing? Probably. And because they were the bottom 20 M the replacements will not do it for cheaper (this is somewhat unique condition for this setup (normal economic thinking assumes that others step up)). Sure some tasks are not worth the new cost and the increased demands might not be that much. But the switchers will reduce laborers for the next wage class (and this recourses as much as it needs to). Doing it at scale means firms feel the statistical impact. Or is the bid that they could full-time self-improve but will statistically significantly choose not to?

The data we've seen from basic income pilots at all scales around the world indicate that guaranteed income may actually increase labor force participation. There are examples of people using it to get an education or do socially valuable care work, but overall RTC study examinations have seen statistically insignificant, slightly increased rates of working.

The major problem most homeless people encounter is that they cannot get jobs, because of various obstacles such as having clean interview clothes, a home address, a bank account, stolen IDs, etc... From the limited prior studies on guaranteed income for homeless and housing insecure people, guaranteed income seems to enable them to gain employment. Unlike conventional benefits, guaranteed income doesn't force people to stay unemployed or refuse promotions by having a benefits cliff.

Hi EA Community, I’d like to introduce my high-impact startup and spark a conversation. I’m also seeking potential co-founders or funders to help get our idea off the ground. I introduced myself last week.

I will discuss

Our Startup Plan: Maximum Impact in Developed Nations.

My recommendation? Effective Altruists should strongly consider helping us grow.

The massive anti-poverty potential of guaranteed income in developed nations, and how we’re stuck in Pilotland.

Guaranteed income is a type of cash transfer program that provides continuous unconditional cash transfers to individuals or households.

Cash transfers are the most widely researched intervention in the world, and also the most consistently positive intervention. While we know that niche global health interventions can outperform cash transfers at small (<$1B/Year) scales, direct cash is the only intervention that can effectively meet the $100+ Billion a year scale of global poverty.

The evidence points strongly towards guaranteed income being the most cost-effective anti-poverty intervention in developed countries. Here's my theory as to why:

Aid Effectiveness = Value Transfer Efficiency

Aid programs are designed (in theory) to bring as much value as possible to people in need. Conventional aid programs help beneficiaries by providing them with goods and/or services.

Unfortunately, it’s expensive to provide goods and services. Paperwork is usually an undignified hassle, and beneficiaries rarely get exactly what they need most in developed nations. Oh, and many interventions are ineffective or actively harmful.

In the developing world, there are a few niche opportunities to distribute basic, cheap, neglected health interventions that can save a lot of lives, more than cash would, at small scales. That said cash assistance is the only non-niche intervention cost-effective enough to end global poverty at scale. Our focus is exclusively on developed nations, and how aid works there.

Guaranteed income is architecturally superior to other forms of aid.

Fundamentally, poor people are way better than nonprofit ‘experts’ at knowing what they need and getting it. For example, if someone needs a car loan and the aid program provides food stamps, they have to launder their food stamps to get the cash for their car loan. Guaranteed income empowers poor people with liquid aid.

The image above shows why guaranteed income is intrinsically more efficient than other forms of aid.

While some still argue that direct cash transfers could harm recipients, by, for example, causing them to gamble or use drugs, there is extremely strong evidence to the contrary from every form of cash transfer experiment. Most guaranteed income proposals in developed nations top out at $1,000 per month, enough to get basic needs, reduce stress levels, and break down harmful stereotypes about people living in poverty, but not enough to live comfortably.

Essentially, funding guaranteed income is the way to spend money to help people in developed developed countries. Here's the situation (Focusing on the U.S. first). There are two important categories of guaranteed income: policy, and the nonprofit industry.

Guaranteed Income (Universal Basic Income) Policy

50% of Americans don’t have $400 in cash on hand to deal with an emergency. That’s a crazy but true statistic, so a national guaranteed income policy would do a massive amount of good. This was proven when the expanded child tax credit (a temporary UBI for families with kids) briefly drove child poverty down by over 40%.

A great article by the Washington Post laid out what’s going on from a policy (government funding) approach in the guaranteed income movement.

“If empirical evidence ruled the world, guaranteed income would be available to every poor person in America, and many would no longer be poor. But empirical evidence does not rule the world.”

Guaranteed Income has a long and storied history in the U.S., which I will quickly skim over as it is not what this post is about. Regarded by historians as the Father of the American Revolution, Thomas Paine, advocated unsuccessfully for a form of universal cash payment in Agrarian Justice. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. advocated it as the only obvious solution to truly ending poverty right up until his assassination. President Nixon nearly passed a Universal Basic Income but was thwarted ironically by a democratic senate that wanted larger payments and a 200-year-old fraudulently administered study. Guaranteed Income then lay mostly dormant until presidential candidate Andrew Yang decided to make a Universal Basic Income his #1 policy priority.

Since then, a ton of publicly and privately funded guaranteed income pilots have proven just how powerful and effective guaranteed income is at helping people. Unfortunately, it seems like getting a guaranteed income passed federally or in any state is highly unlikely for now.

Several organizations exist to push guaranteed income policy, such as the Economic Security Project, and Mayors for Guaranteed Income, so we’ve decided to pursue a different neglected route to proliferating guaranteed income.

Our work won’t get roadblocked by politics and presents an opportunity with a very high chance of success. As we scale, our work will accelerate the progress of all the existing organizations working towards a guaranteed income policy.

Our Focus: The Nonprofit Industry

The Guaranteed Income Movement is living in Pilotland. Over 100 guaranteed income pilots have recently been announced or completed in cities across the U.S. There’s a problem though. As new pilots get announced, old pilots end and fizzle out. We keep seeing the same cycle across the country:

There are few if any cases of pilots leading to the establishment of long-term guaranteed income programs. This is a shame because guaranteed income has proven much more consistently impactful than all other anti-poverty interventions.

Americans gave $484.85 billion in 2021. The nonprofit industry brings in hundreds of billions of dollars each year. Not governments, just private foundations, corporations, and philanthropists.

Why aren’t they spending their money on guaranteed income?

The clearest answer is that they do when given the chance. But that only happens when there is a guaranteed income pilot in their area. Most nonprofits and funders in general have geographic limits on where they spend their money. Many also have limits on the sorts of people they are allowed to help (youth vs LGBTQ vs African American vs veterans, etc...). If there isn’t a guaranteed income pilot in a specific town, none of the funders that live there will be spending any of their money on guaranteed income.

They are not free to spend their money on whatever thing, anywhere on earth, has the largest impact potential. They can only spend money within their limits, and guaranteed income will almost always be the most impactful thing they could spend it on because almost all of them are limited to developed nations.

Imagine you’re a funder living in Pilotland, where tons of varying experiments are going on all over the place. If you’re looking to make an impact, the odds are strong that there are not any guaranteed income pilots within your geographic limits helping the people you exist to help. You can either create a program yourself or deal with the less effective options on your plate.

Our Big Idea: Building a platform to unleash the massive anti-poverty potential of guaranteed income.

Although there are logistical complications, cash is easier to administer than any other intervention, enabling us to create a platform for fundraising, and disbursing guaranteed income within all geographic areas and for many kinds of populations in need. The idea is two-fold.

As the scale of guaranteed income programs increases, each incremental staff member can manage more and more participants. A $100M program, for example, funding 4,166 participants at $1K per month for two years -- with automation -- should require less than 1 staff hour spent per incremental participant. That equates to less than 1 full-time worker over 2 years. The vast majority of that time is required right at the beginning, however, so onboarding participants must be effectively spread out over time. As such, a reasonably sized team with staff specializing in specific roles could manage well over 1,000 additional participants per incremental staff member.

One lean team of ~20 could, we believe, manage to disburse $100M+ a year. At that scale, the bank interest from funds pending disbursement could theoretically exceed the amount needed to operate the platform.

Many details are still in development, and we will publish “Foundation’s Basic Income Network Whitepaper” when it is ready. We have had this concept reviewed by over a dozen nonprofit and financial professionals, so we are confident that it is likely to work. If we can get it off the ground (<$5M we estimate), it should be able to unleash the massive anti-poverty potential of guaranteed income.

Why should we be the ones to build this?

We started a new nonprofit to exclusively focus on this for a few reasons. First, I realized that while GiveDirectly could build the platform, it might go against their #1 value of "putting the poor in control of how aid money is spent". If we want to maximize funders, we have to work within their bounds, and I think GiveDirectly might not be ok with sending money to people that are not desperately poor.

And that could be a very good thing! GiveDirectly probably should focus on international cash transfers, because building this platform would quickly make their extremely important global poverty and crisis response work a very tiny fraction of their overall funding. Such a situation could lead to GiveDirectly (unintentionally, of course) losing focus on eliminating global desperate poverty and crisis response. They are doing fantastic work developing crisis response, and our platform won’t be designed for that sort of need.

I think it would be better for us to focus entirely on developed countries ourselves (with Aidkit or some other infrastructure contractor), sending all funds that we get from funders without geographic limits to GiveDirectly (after fully funding GiveWell's top charity fund). Doing so would enable us to focus on the platform, and help accelerate GiveDirectly’s work. That said, we would love to collaborate with them on fundraising and improve our system with their experience.

Our Theory of Change. How can we scale to the levels needed to meaningfully reduce poverty and end homelessness?

Personal Note

I posted a blog last week introducing myself and where my expertise lies. I've put in ~10,000 hours analyzing & predicting disruptive systems (eg, understanding emerging technologies and shaping them to make the future better).

I hypothesize that guaranteed income is such a system, although it is not a hardware-based technology like solar or the internet. I’ll first explain how I see us scaling our impact, and then I’ll try to explain some larger principles with the help of the Seba Technology disruption framework.

Our theory of change

Every successful company, technology, and societal change has come about through the creation of powerful virtuous cycles. We believe that our system can leverage guaranteed income to create increasingly large direct impacts while establishing cash as the baseline for nonprofit interventions in developed nations.

The steps:

Our Theory of Change + The Seba Technology Disruption Framework

Seba Technology Disruption Framework, Guaranteed Income

Potential Weak Points in our Theory of Change

The biggest weak point in our plan could be our ability to fundraise for guaranteed income at scale cost-effectively. We'll have to convince lots of donors and funders of all kinds of the accurate but (potentially) counter-intuitive notion that directly giving cash to people in need is an extremely effective way to help them. Although we have overwhelming evidence, age-old misconceptions about the lazy or undeserving poor may make our expansion plans underperform. Our ability to make a truly transformational impact is reliant upon the capability of our fundraising machine. Having experienced fundraisers and narrative-change professionals on our team would greatly mitigate this weak point.

ITN Framework: Poverty+Guaranteed Income

Importance (Scale of the Problem in America alone)

Poverty is the UN’s #1 SDG for a reason. Arguably, poverty is the biggest problem in the world and the root of almost every other (non-existential risk) problem humanity faces.

Child poverty alone cost $1.03 Trillion in 2015, a massive sum that is equivalent to approximately 1/3 of the entire federal budget. During the coronavirus, the expanded child tax credit (a small UBI for families with kids) drove child poverty down by over 40%, and then it rebounded when the program ended.

Other forms of poverty across various groups also have negative economic impacts. And above the arbitrary federal poverty line, there are far more negative opportunity cost impacts that dwarf the 1 Trillion per year figure. While the official poverty rate is 11.6%, 7 in 10 Americans struggle with at least one aspect of financial stability, and 40% are struggling to pay for basic needs.

Additionally, a surprisingly large amount of Americans have very unpredictable changes in fortune year after year. More than half of the population experiences a median swing of 7.5 points (out of a 100-point score of financial health). Rob Levy, vice president of research and measurement at the Financial Health Network said, "We didn't think people's lives would change that much," but it turns out that, “most Americans' financial prospects are "like a game of 'Chutes and Ladders,' which has implications for stress.”

Tractability (Solvability)

The large-scale interventions we’re currently using (the welfare system and a fractured assortment of low-impact nonprofits) are not effectively reducing poverty. We need to leverage the most effective intervention against poverty that is also highly impactful at any scale.

Essentially, guaranteed income can solve poverty. Research by Karl Widerquist of Georgetown University shows that it would cost only $539 Billion, less than 3 percent of the U.S. GDP, to permanently end poverty with Universal Basic Income. Widerquist says the $539 billion per year is 2.95 percent of America’s GDP is about one-sixth of the cost of commonly circulated estimates, and that this amount is less than 25 percent of current entitlement programs.

Widerquist’s research used U.S. Census Bureau data for 2015 to examine an estimated poverty-level UBI of $12,000 per adult and $6,000 per child. It also found that some 43.1 million people (including 14.5 million children) would benefit from this increased income, reducing the poverty rate from 13.5 percent of the population to zero.

That said, driving policy change is difficult, so guaranteed income likely won’t happen until the political will exists among special interests and major political donors. Sadly, the preferences of the average American appear to have only a minuscule, near-zero, statistically non-significant impact upon public policy.

Without relying on finicky government policy to proliferate guaranteed income, we believe that our platform can empower the nonprofit industry to fund guaranteed income at scale, ending the homelessness crisis and taking a decent % chunk out of poverty. Over time, should the government fail to pass guaranteed income policy, our platform could be able to reach the total scale of poverty in the U.S.

Should the government succeed, we'd still be able to do a great deal of good by making the nonprofit industry spend its aid money on (extra) guaranteed income.

Neglectednesss

There are a lot of organizations and people working to reduce poverty, and trillions are spent each year fighting it. Of course, our focus is on the neglected intervention with the potential to solve it.

There are a few guaranteed income organizations already dedicated to creating the policy change that could establish a Universal Basic Income. It seems that almost all organizations in the guaranteed income movement are focused exclusively on policy change, one niche community, or one niche population in need. That’s not to say policy change funding isn’t neglected, just that there are already many organizations and people working on that.

There are no other organizations, however, with the vision to build what we want to build. All nonprofit guaranteed income providers in the developed world seem to be limited by geographic region, the population they are focused on helping, or some combination of the two.

Unleashing the full existing funding potential for guaranteed income is a completely neglected yet important part of the solution to poverty.

The implications of guaranteed income for humanity and the Effective Altruism Movement.

We believe the growth of our guaranteed income platform in the medium term could have very large positive impacts against poverty and for the EA movement such as

The likelihood of this? Given the research, I've outlined, and the input that I've received from a bunch of unbiased professionals in the nonprofit industry, I think the likelihood is closer to 40% if we do not get any support from EA, and over 70% if we do get tons of support.

Longtermist implications of guaranteed income

This is the most speculative part of the post, so it may be best to just skip it.

Guaranteed income at scale, universal basic income (UBI), could be the logical foundation (see what we did there), for human civilization. If money remains a thing and capitalism continues to look like the most efficient system for getting people the things they want, then guaranteed income should be one of the fundamental positives in the long-term future of humanity. Think of all the impacts outlined in the above sections, but repeated for tens, or thousands of generations to come. Global (or civilizational, should we escape Earth) guaranteed income could be an important part of permanently ending resource-based conflict and enabling humans to become more aligned.

In the same vein, establishing UBI as a human right could make it much harder for a (non-AI) actor to enslave humanity forever, reducing several S-risks. Given the dispersed power that UBI distributed evenly across society, people would be much more prepared for and highly resilient to malicious actors looking to entrench power.

If the disruption enabled by guaranteed income is inevitable. Our impact could therefore be accelerating the disruption while ensuring that guaranteed income isn’t used for negative purposes. Dictatorial governments could, for example, tie social credit scores to the amount of a basic income. In the wrong hands, guaranteed income could be an extremely powerful tool to entrench social stratification. We can help to ensure that the growth of basic income is safe, effective, and dignified.

We also have an idea for a Basic Income Endowment, which would enable funders to generate guaranteed income in perpetuity. It would be the most impactful way of establishing a meaningful permanent legacy for any wealthy person. Over time, it could become very large, perhaps large enough to provide guaranteed income to all of society.

This potential future excites me, and I’d like to see what other longtermist effective altruists think about it.

Our Startup Plan: Maximum Impact in Developed Nations.

We've found a niche opportunity to build the most cost-effective anti-poverty program in America (an ~$50M opportunity before cost-effectiveness starts to decrease). We believe that funding capacity-building for our Maximum Impact Pilot could outperform even GiveWell's top charities in cost-effectiveness.

Experimental results support the cost-effectiveness of guaranteed income against homelessness.

Importantly, the fact that we’ve identified this problem in the U.S. means that EA doesn't need to fund it (just help us get established). There's tons of local funding available which we intend to pursue, so EA capacity-building funding would result in 10X the impact of spending on the intervention. Furthermore, all of the local funders are not willing or able to spend outside of their geographic limits so the funding we receive for this intervention wouldn't reduce funding for global EA interventions.

A small but growing collection of experiments have been showing that guaranteed income, giving large structured sums of unconditional cash to people suffering from homelessness, can help most unhoused people (chronic sufferers and recently unhoused people) escape the streets and regain economic security. Compared to the other effective intervention against homelessness, housing first (which is theoretically 100% effective), guaranteed income experiments have demonstrated >66% housing success rates at a tiny fraction of the cost per beneficiary (see California’s $694M program that costs $50,000 to $277,000 per person). We believe a large-scale well-structured guaranteed income program could make homelessness solvable.

Experiment results and implications

Based on the results of these experiments, we’ve concluded the following. There is a:

Contrary to some popularly held assumptions, our research points strongly towards almost all homeless people spending guaranteed income transfers on meeting their basic needs and quickly working to regain economic security when given the opportunity, (USC Literature Review and Our Research).

Furthermore, there is extremely low downside potential. There are almost no recorded cases where guaranteed income has caused harm (to homeless people or in general), despite there being a very large amount of data available for cash transfers in general. Even in cases where one could anticipate that guaranteed income would enable participants to do bad behavior, they have not done so.

Almost all spend resources on basic needs, followed by rent, housing supplies, and other things that help them get ahead. It may even be an incredibly counter-intuitive yet cost-effective way to reduce drug usage. Of course, a lot more research needs to be done before rolling out guaranteed income as a drug abuse reduction intervention.

That said, it's important to remember that the general public is also full of drug users (have you used alcohol or cannabis in the last year?). We judge ourselves and our friends at a lower standard than we do people forced to live on the streets. Furthermore, there's a big difference between drug use and drug addiction, and drug use, in moderation, is not inherently negative. Finally, it's nearly impossible to accurately determine who does how many drugs without extremely invasive, undignified, & expensive oversight that would result in few participants wanting to engage in the program. The best way to measure whether participants are spending their money 'right', is by recording their quality of life before, during, and after guaranteed income.

We’ve spoken with local advocates from groups such as FeedPhoenix and AZ Hugs for the Houseless, representatives from groups studying guaranteed income, a wide range of unbiased nonprofit professionals (Stuart Turgel, Carol Farabee, Rodney Houston, etc...), and organizations doing research into this intervention. During our conversations, people with experience fighting homelessness have agreed that guaranteed income at scale could help around 2/3 of homeless people regain stability, diminishing the crisis to manageable levels.

Ending homelessness at a fraction of the cost

We believe that if a small fraction of the current amount spent on homelessness is allocated to a well-run guaranteed income program, it would likely help the majority of homeless people get off the streets. Guaranteed income makes homelessness solvable and could turn the homelessness industrial complex from an infinite dehumanizing money sink to an opportunity to invest in people while they re-enter society.

Keeping people on the streets costs between 45-180K (accounting for inflation) because they, “randomly ricochet through very expensive services” such as hospitals, addiction treatment services, police arrests, jail time, and court time. The federal government is spending $51 Billion a year and California alone is spending over $10 Billion. $61B / 552,830 homeless people = $110,341.

We’re spending significantly more than $110,341 per homeless person in America per year. We could afford to provide a guaranteed income of $1,000 a month to all of them for around 10% of our current spending. More accurately, we can’t afford not to.

Guaranteed income, the intervention with the potential to solve the problem, is neglected. Not because people know about it and have decided not to fund it, but because they have not heard about it at all. Currently, a few organizations are experimenting with guaranteed income for fighting homelessness, but only one (startup) nonprofit is focusing on Arizona or using a platform strategy to reach the full scale of the problem. That’s us.

We believe that even a very small investment to help establish our nonprofit (a few million dollars), would be sufficient to build a team that can fund a program that meets the scale of the homelessness crisis at scale within a few years.

Arizona is by far the deadliest place in the U.S. for homeless people.

Homeless people in Arizona are among the most vulnerable people in the world. Primarily because of Arizona’s summer heat, the preventable death rate among Arizona’s homeless population is 7% annually. I couldn’t find any other population with a higher preventable death rate outside of war or genocide after searching through the Human Mortality Database. I’m sure the population of stage 4 cancer patients, for example, also has a high death rate, but those are not easily preventable deaths.

The Math

Arizona’s (Maricopa County’s at least) Homeless Death Rate from 2020:

Deaths / Total population: 595 / 7,419 = 8%

The overall homeless mortality rate in Arizona is ~8%. After subtracting the natural 1% U.S. mortality rate, we find the mortality rate increase due to homelessness in AZ is 7%. This is, of course, an educated estimation based on the best numbers available.

Overwhelming demographic data as well as medical analysis make it evident that living on the streets directly accounts for most, though not all, of the massive mortality rate increase. There is a causal relationship between living on the streets and high death rates, especially in Arizona due to the high summer heat. California, which has a much more temperate climate, has ~5,000 homeless deaths within a population of 173,800, a 2.8% mortality rate.

What does this mean for 2022?

2022 Point-In-Time count of homeless individuals data:

There are at least 13,553 homeless people in Arizona.

2022 Estimated AZ Homeless Deaths = 13,553 * 8% = 1,084

2022 Estimated Preventable Homeless Deaths in AZ = 13,553 * 7% = 948.5

The true outcome could differ by a few hundred up or down, but this number will also increase because the homelessness crisis is getting consistently worse year over year.

QALYs (Quality-Adjusted Life Years) expected from Foundation's Maximum Impact Pilot

We’ve designed our pilot to become the most impactful anti-poverty program in America. To do so, we’ll be helping homeless individuals in Arizona with guaranteed income.

We will be giving ~24 homeless participants in our pilot $6,000 over 6 months ($1,000 per month) while helping each of them connect to the local services they need to regain stability. We chose 24 because it resulted in the smallest budget where we could still send 80% of the budget directly to people in desperate poverty. This assistance will greatly help nearly every participant over the first year, and our goal is to help at least 50% of the participants achieve permanent housing stability. We consider this to be a conservative goal because every homelessness cash-assistance pilot to date has helped at least 66% of participants achieve stability.

The Facts

living in homelessness reduces one's QALY (quality-adjusted life year) from 1.0 to 0.434, so helping someone stay out of homelessness would save 1 - 0.434 = 0.566 QALYs per year they would otherwise be homeless. (Academic Source: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34629422/)

According to William MacAskill in Doing Good Better, Health economists estimate that the benefit of “preventing a preventable death” is equivalent to saving 36.5 QALYs.

With approximately 8% of the homeless population dying every year (7% higher than the normal 1% rate), each Participant we help will have their death likelihood reduced to the mean (by 7%) during the pilot year. Then there will be lasting reductions in mortality rates for participants that permanently exit homelessness. (7% per year housed vs. the counterfactual)

The Math