This post attempts to give a more intuitive explanation of my perspective-based solution to anthropic paradoxes. By using examples, I want to show how perspectives are axiomatic in reasoning.

For each of us, our perceptions and experience originate from a particular perspective. Yet when reasoning we often remove ourselves as the first-person and present our logic in an objective manner. There are many names for this way of thinking, e.g. “take the third-person view”, “use an outsider’s perspective”, “think as an impartial observer”, “the god’s eye view”, “the view from nowhere”, etc.

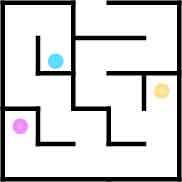

I think the best way to highlight the differences between god’s-eye-view reasoning and first-person reasoning is to use examples. Imagine during Alex’s sleep some mad scientist placed him in a maze. After waking up, he sees the scientist left a map of the maze next to him. Nonetheless, he is still lost. Here we can say, given the map, the maze is known. Alex is lost because he doesn’t know his location.

Figure 1. From a god’s eye view, the maze’s location is known. But Alex’s location is unknown. The colored dots show some possibilities given Alex’s immediate surroundings.

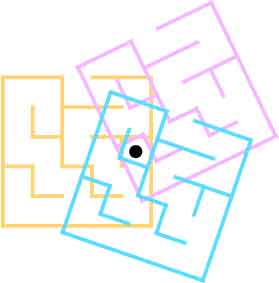

In contrast, an alternative interpretation is to think in Alex’s shoes. I can say of course I know where I am. Right here. I can look down and see the place I am standing on. No location in the world is more clearly presented to me than here. I’m lost because I don’t know how is the maze located relative to me, even with the map.

Figure 2. Here is known. The maze’s location is unknown. The colored parts show some possibilities.

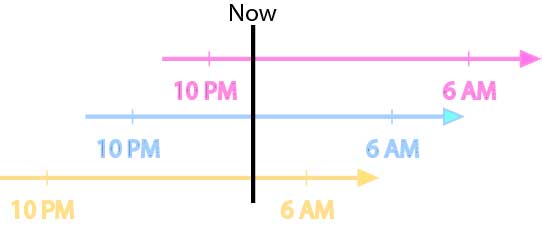

This difference also exists in examples involving time. Imagine a thunder wakes Alex up at night. Here we can say he doesn’t know what time it is. Maybe he went to bed at 10 pm and his alarm clock rings at 6 am. There is no information to place his awakening on the time axis.

Figure 3. From a god’s eye view, it is known when Alex went to bed and when the alarm clock is going to ring. But the time when the thunder wakes him up is not known. Colored lines show some possibilities.

Alternatively, we can think from Alex’s perspective as he wakes up. I can say of course I know what time it is. It is now. It is the time most immediate to my perception and experience. No other moment is more clearly felt. What I don’t know is how long ago was 10 pm when I went to bed, and how far in the future will my alarm clock ring at 6 am, i.e. how other moments locate relative to now.

Figure 4. Now is known. But how other moments locate relative to now is unknown. The colored part shows some possibilities.

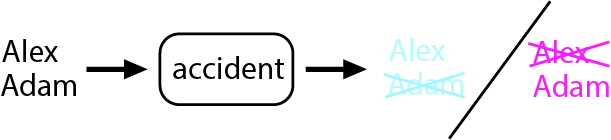

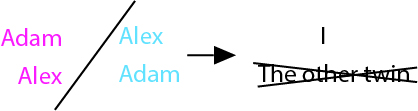

The same difference also exists when identities are involved. Imagine Alex and Adam are identical twins. They got into a fatal accident while traveling in the same vehicle. One of them died while the other suffers complete memory loss. If they look the same and have the same belongings, it can be said there is no way to tell who survived the tragedy.

Figure 5. The past is known. The survivor is unknown. The colored parts show two possible outcomes.

There are other ways to describe the situation. For example, if we take the perspective of the survivor, it is obvious who survived the accident. I did. This self-identification is based on immediacy to the only subjective experience available: all senses felt are due to this body. No other persons or things are more closely perceived. Whether I was Alex or Adam, however, is unknown. In a sense, I don’t know how was the world located relative to me.

Figure 6. Obviously, I survived the accident while the other twin didn’t. However, the past is unknown. Whether I was Adam or Alex is lost. Colored parts show the two possibilities.

These examples show how different perspectives analyze problems differently. Without getting into all the details I want to stress the following points:

- First-person thinking is self-centered. Special consideration is given to here, now, and I. The perspective center is regarded as primitively understood due to its closeness to perception and subjective experience. It is the reasoning starting point. Other locations, moments, and identities are defined by their relative relations to the perspective center.

- First-person and god’s-eye-view are two distinct ways of reasoning. They should not be used together. For example, in the maze problem, we cannot say both the maze’s and Alex’s locations are known. While the former is true from a god’s-eye-view and the latter is true from Alex’s first-person perspective, mixing the two would make the whole “lost in the maze” situation unexplainable.

Anthropic problems are unique because they are formulated from specific first-person perspectives (or a set of perspectives). There is no straightforward god’s-eye-view alternative.

Take the sleeping beauty problem as an example. It asks for the probability when beauty wakes up in the experiment. However, there may be two awakenings. From a god’s eye view, the problem is not fully specified. Which awakening is being referred to? Why update the probability base on that particular awakening? But things are clear from beauty’s first-person perspective. I should obviously update my belief base on my experience: base on this awakening right now, the one I have experience of. From beauty’s point of view, today is primitively understood, no clarification is needed to differentiate it from the other day. And we intuitively recognize the problem is asking about a specific awakening/day.

Paradoxes ensue when we try to answer the problem from a god’s eye view while keeping that intuition. As pointed above, the awakening is not specified from god’s eye view. We mistakenly try to fill in the blanks with additional assumptions. For example, regard this awakening as randomly selected from all awakenings (Self-Sampling Assumption), or regard today as randomly selected from all days (Self-Indication Assumption). By redefining the first-person center from the god’s eye view, these assumptions provide the seemingly missing part of the question: which specific awakening is being referred to, and why update the probability base on that particular awakening.

Different anthropic assumptions give different answers, which also leads to different paradoxes. However, these assumptions are redundant because the question should have been answered the same way it is asked: from Beauty’s first-person perspective. There is no reference class for I, here, and now. They are primitively identified right from the start, not selected from some similar group. Even the superficially innocent notion of “I am a typical observer” or “now is a typical moment” is false. From a first-person perspective, I, now, and here are inherently special as shown by the self-centeredness.

The correct answer is simple. From Beauty’s viewpoint, there is no new information as I wake up in the experiment. Because finding myself awake here and now is logically true from the first-person perspective. The probability stays at 1/2. From a god’s eye view, all that can be said here is there’s (at least) one awakening in the experiment.

Some argue there is new information. That being awake on a specific day is evidence suggesting there are more awakenings. Halfers typically disagree by saying it is unknown which day it is. Thirders counter that by saying Beauty knows it is today. Halfers often argue today is not an “objective” identification. Thirders response by saying all the details Beauty sees after waking up can be used to identify the particular day. For example, the experimenter can randomly choose one day and paint the room red and paint the room blue on the other day. If Beauty sees red after waking up, then we know Beauty is awake on the Red day. Which is unknown before. Some argue this new information favors more awakenings.

To that, I would ask: out of the two days, why update the probability base on what happens on the Red day? Why not focus on what happens on the Blue day and update the probability instead? Thirders may find this question painfully trivial: because what happens on the Blue day is not available. Beauty is experiencing the Red day. That’s reasonable. However, that means it doesn’t matter if we use the word today or use details observed after waking up, that particular day is still specified from Beauty’s first-person perspective. Yet from a first-person perspective finding myself awake here and now is expected. The argument for new information switches to a god’s eye view. As if an outsider randomly selects the Red day then finds Beauty awake. This argument depends on first-person reasoning -to specify the day, and god’s-eye-view reasoning -to calculate the prior probability of finding Beauty awake on said day. It mixes parts from two perspectives. (For a more detailed analysis see my argument against Full Non-Indexical Conditioning and perspective disagreements)

As Beauty wakes up in the experiment, some may ask “what is the probability that today is Monday?”. The answer is interesting: there is no such probability. Remember as the first-person, the perspective center is the reasoning starting point. This includes I, here, now, and by extension today. Like axioms, they cannot be explained by logic or underlying mechanics. They are identified by intuition- by their apparent closeness to subjective experience. So there is no logical way to formulate a probability about what the perspective center is.

One has to mix first-person and god’s-eye-view to validate this probability. For example, we can do so by accepting any one of the anthropic assumptions. They redefine today/this awakening as a randomly selected sample from some proposed reference class. Doing so means we can reason from a god’s-eye-view and justifies the principle of indifference to all days/awakenings. However, as discussed before, this mix is false. Now is a first-person concept that is inherently unique from all other moments. A principle of indifference categorically contradicts the self-centeredness of the first-person view. (For a more detailed discussion against self-locating probability, and why they are invalid from the frequentist or decision-making approach see my argument here).

I doubt we’ll persuade each other :) As I understand it, in my example you’re saying that the moment a self-location is ruled out, any present and future updating is impossible – but the last known probability of the coin stands. So if Beauty rules out Heads/Peter and nothing else, she must update Heads from 1/2 to 1/3. Then if she subsequently rules out Tails/Peter, you say she can’t update, so she will stay with the last known valid probability of 1/3. On the other hand, if she rules out Tails/Peter first, you say she can’t update so it’s 1/2 for Heads. However, you also say no further updating is possible even if if she then rules out Heads/Peter, so her credence will remain 1/2, even though she ends up with identical information. That is strange, to say the least.

I’ll make the following argument. When it comes to probability or credence from a first person perspective, what matters is knowledge or lack of it. Poeple can use that knowledge to judge what is likely to be true for them at that moment. Their ignorance doesn’t discriminate between unknown external events and unknown current realities, including self-locations. Likewise, their knowledge is not invalidated just because a first person perspective might happen to conflict with a third person perspective or because the same credence may not be objectively verfiable in the frequentist senes. In either case, it’s their personal evidence for what’s true that gives them their credence, not what kind of truth it is. That credence, based on ignorance and knowledge, might or might not correspond to an actual random event. It might reflect a pre-existing reality - such as there is a 1/10 chance that the 9th digit of Pi is 6. Or it might reflect an unknown self-location – such as “today is Monday or Tuesday”, or “I’m the original or clone”. Whatever they’re unsure about doesn’t change the validity of what they consider likely.

You could have exactly the same original Sleeping Beauty problem, but translated entirely to self-location without the need for a coin flip. Consider this version. Beauty enters the experiment on a Saturday and is put to sleep. She will be woken in both Week 1 and in Week 2. A memory wipe will prevent her from knowing which week it is, but whenever she wakes, she will definitely be in one or the other. She also knows the precise protocol for each week. In Week 1, she will be woken on Sunday, questioned, put back to sleep without a memory wipe, woken on Monday and questioned. This completes Week 1. She will return the following Saturday and be put to sleep as before. She is now given a memory wipe of both her awakenings from Week 1. She is then woken on Sunday and questioned but her last memory is of the previous Saturday when she entered the experiment. She doesn’t know whether this is the Sunday from Week 1 or Week 2. Next she is put to sleep without a memory wipe, woken on Monday and questioned. Her last memory is the Sunday just gone, but she still doesn’t know if it’s Week 1 or Week 2. Next she is put back to sleep and given a memory wipe, but only of todays’s awakening. Finally she woken on Tuesday and questioned. Her last memory is the most recent Sunday. She still won’t know which week she’s in.

The questions asked of her are as follows. When she awakens for what seems to be the first time – always a Sunday – what is her credence for being in Week 1 or Week 2? When she awakens for what seems to be the second time – which might be a Monday or Tuesday – what is her credence for being in Week 1 or Week 2?

Essentially this is the same Sleeping Beauty problem. The fact that she has uncertainty of which week she’s in rather than a coin flip, doesn’t prevent her from assigning a credence/probability based on the evidence she has. On her Sunday awakening, she has equal evidence to favour Week 1 and Week 2, so it is valid for her to assign 1/2 to both. On her weekday awakenings, Halfers and Thirders will disagree whether it’s 1/2 or 1/3 that she’s in Week 1. If she's told that today is Monday, they will disagree whether it's 2/3 or 1/2 that she's in Week 1.

We could add Bob to the experiment. Like Beauty, Bob enters the experiment on Saturday. His protocol is the same, except that he is kept asleep on the Sundays in both week. He is only woken Monday of Week 1, then Monday and Tuesday of Week 2. Each time he’s woken, his last memory is the Saturday he entered the experiment. He therefore disagrees with Beauty. From his point of view, it’s 1/3 that they’re in Week 1, whereas she says it’s 1/2. If told it's Monday, for him it's 1/2 that they're in Week 1, and for her it's 2/3.

This recreates perspective disagreement – but exclusively using self-location. You might be tempted to argue that neither Beauty or Bob can ever assign any probability or likelihood as to which week they’re in. I say it’s legitimate for them to do so, and to disagree.