I am a bit confused by this claim, because cities are excellent for social, emotional, and intellectual life. They put you close to museums, theaters, and other art and entertainment; to libraries, bookstores, and music stores; to workshops where you can try crafts; to tutors and classes where you can learn singing, yoga, tennis, ballet, or anything you like. By putting you in more contact with more people, they make it more likely for you to find people who share your hobbies, interests, and values—your niche, your community, your people—the perfect friend, business partner, comrade, or soulmate.

Is there such thing as the perfect friend, business partner, or soulmate?

If you lived in a small rural with a few close relationships, you of course don't hope for such a thing (And even less so in a pre-agrarian tribe). You practice acceptance, forgiveness, and sacrifice for the people you do know.

Certainly progress has been better at meeting our desires... But from a spiritual perspective, is it meeting desires that leads to spiritual growth and fulfillment

From a Buddhist perspective the worst thing you could do is satisfy every desire, give people more options and the illusion that you can remove suffering by satisfying craving (this just gives you more craving and suffering).

Upvoted for exploring the topic, but tempted to downvote for missing the most important and least discussed aspect of the change: population size.

The VAST majority of people living today would not only have had a worse standard of living pre-industrial-revolution, they would simply not exist at all. Unless you have a solid theory of marginal value of a life, other arguments are secondary.

The vast majority of chicken would not have existed but for the meat industry. Would you accept that argument?

It's a trickier argument, because there's less evidence that chickens consider their lives worth living, but on the whole, yes.

edit: don't take this too far. I care about chickens a whole lot less than I care about humans, AND most chicken lives are closer to the line (and the error bars cross it) of "not worth living". We're nowhere near the repugnant conclusion line for humans, we might be for chickens. Fortunately for them, they remain delicious.

So synthetic meat, once it becomes technically feasible to do so and cheaper, would result in farm animal genocide. Since theoretically you could go directly between photosynthetic plants like algae -> purified nutrients -> growth media for synthetic meat -> synthetic meat.

This would at scale be far more efficient.

The only remaining cows and chickens would be as pets, zoo animals, and for exotic restaurant fair.

I would expect that over time eating real meat would be frowned upon like how eating dog is becoming socially less acceptable even in countries that still do it.

Yes? This seems like a net good. Cows and chickens are like Cauliflower in that they need a very specific and controlled environment to produce market level produce.

Genocide seems like the wrong word here. If you understand it as removing a group of genes, then you're correct. If you mean it as the large scale butchering of a group, then that's sort of the whole point of farming them?

If you believe these animals are somewhat sentient with worthwhile individual qualia, then the consequences of cheap and perfect synthetic meat would be a reduction in number to less than 1 percent the current population.

So given those assumptions it's genocide. I am not saying I believe they are sentient but presumably once we invent "neural debuggers" we will be able to answer this.

(Perfect synthetic meat: a close enough substitute that blind A:B testing cannot distinguish the difference. Neural debugger: technology to connect trillions of wires, either physically or though light, all throughout a running meat brain so that it's functions can be fully analyzed and understood.)

But most workers were not skilled craftsmen—the “cobblers and furniture makers and silversmiths” referred to in that thread. Far more representative would be, say, women spinning yarn at home to bring in extra household income. This was a routine, tedious chore, and most women did it not because they found “vocation and purpose” in the work, but because they didn’t have much choice.

I think this argument could be made a lot stronger if it would quantify the difference and speak about how much time the average women spent with spinning yarn at home.

TL;DR: the section on vocation makes a lot of unsupported assertions and "it seems obvious that" applied to things which are not at all obvious.

[T]o think that we suffered a net loss of vocation and purpose, is either historical ignorance or blindness induced by romanticization of the past.

You need to put a number on this before I'm willing to accept that this is true. Two particular points you raise are definitely not changed from pre-industrial times: intellectual jobs are still rare and only available to a privileged few, scientists are still reliant on patronage (now routed through state bureaucracies rather than individual nobles, but still the same thing), and actual professional artists were and are such a small portion of the population that I don't think you can generalize much from them.

Meanwhile, count up all of the jobs that today are in manufacturing, resource extraction, shipping, construction, retail, and childcare. To this number we should add the majority of white-collar email jobs, which I argue are not particularly fulfilling---people may not hate working in HR or as an administrative assistant, but I doubt that most of these people feel that it's a positive vocation. Is the number very different from the number of people who were peasants beforehand? Are we sure that this represents progress rather than lateral movement?

More to the point, there are some unexamined assumptions made here about what counts as "vocation", and what kinds of occupations are likely to supply it.

- Anecdotally, the farmers and ranchers I know have a very strong sense of vocation, and high job satisfaction all around (modulo the fact that they are often financially pressed). The article, however, seems to treat agriculture as automatically non-vocational.

- As alluded to above, white-collar work often seems to lack the sense of vocation and pride of work. The article above wants to lump them in with "intellectual jobs" and assumes that they are automatically preferable to alternatives.

- A notable exception to the previous is IT, but we note that programmers are best considered a modern example of skilled craftsmen.

- Generally, the article wants to conflate vocation with choice, which I believe is false.

A better way of drawing the distinction is between "bullshit" and "non-bullshit" jobs, and one might then observe that modernity has a much higher proportion of bullshit jobs than pre-modernity. But expounding that requires a full post of its own.

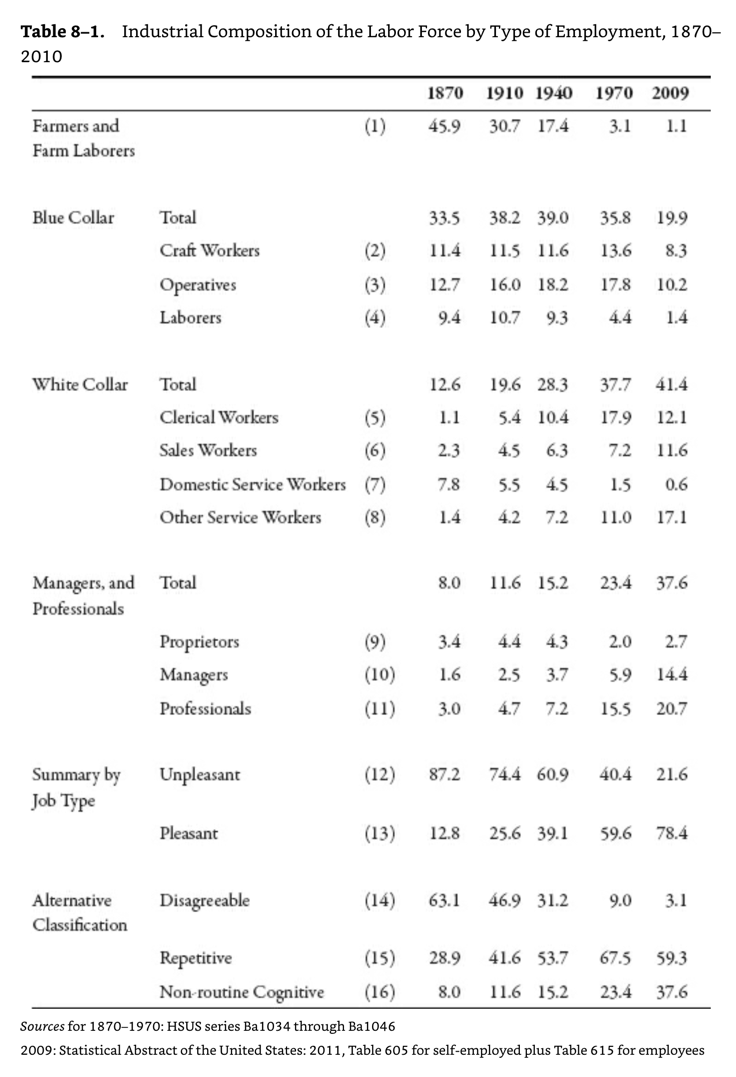

Here's some quantification, from Robert Gordon's The Rise and Fall of American Growth. In 1910, 47% of US jobs were what Gordon classifies as “disagreeable” (farming, blue-collar labor, and domestic service), and only 8% of jobs were “non-routine cognitive” (managerial and professional). By 2009, only 3% of jobs were “disagreeable” and over 37% were “non-routine cognitive”. See full chart below.

I did not say or mean that agricultural is non-vocational. But I think it is not the ideal vocation for 50+% of the workforce.

Vocation is not the same as choice, but when you have choice, you are more likely to find your vocation. That is the point.

Vocation is not the same as choice, but when you have choice, you are more likely to find your vocation. That is the point.

I think we have little idea how "vocation" works. It could be like marriage where cases of arranged marriage don't reduce the likelihood that someone develops love.

I think my strongest disagreement here is that the category of "disagreeable" does not cleave reality at the joints, and that the category "non-routine cognitive" contains a lot of work which is not, in fact, intellectually or spiritually fulfilling in the way implied.

Is that disagreement enough to change the (predicted) truth value of Jason's claim though?

I'll admit to being biased here. I live in a rapidly-developing middle-income country; the difference in opportunity between my generation and my parents is nearly as vast as between 1910 and 2009 in Gordon's statistics. To me, while I agree wholeheartedly that Gordon's categorization doesn't cleave reality at the same joints Jason's does, it's still ~irrelevant in that it doesn't change my mind on the directionality of Jason's claim.

The Industrial Revolution gave us abundance and comfort—but what did it do to our souls?

Recently my progress colleague Alec Stapp responded to a Twitter thread disparaging the Industrial Revolution for what it “did to humanity.” Alec’s response was basically that abundance is good, and I agree. But a few people (e.g., Michael Curzi, Jon Stokes) criticized this response for basically reasserting the material benefits and seeming to ignore the non-materialistic concerns in the original thread.

So, let’s talk about spiritual values—that is, emotional, intellectual, social, and other psychological values—and what industrial progress has done for or to them.

The charges

The original thread, from a pseudonymous account, was a cris de coeur. Let me extract its core arguments. It charges that the Industrial Revolution:

Summing up, she acknowledges that raising living standards was good, but laments that “no one thought to apply the brakes” and that our lives are now “framed by consumerism and commerce.”

Note, this is not from a left-wing environmentalist or a degrowther: she goes on to say that “the unmooring of humanity from its eternal purpose” is “anti-Christ.” This is a religious conservative criticism of progress.

First I’ll address the specific charges, and then I will step back to consider the wider question of how industrialization has affected our spiritual life.

Vocation and purpose

The first charge is against the transition from cottage industry to the factory system. To steelman this, it’s true that this transition took away a certain style of working, and that many people were unhappy about it. Workers in general disliked being supervised by a foreman and thus losing their autonomy to do their work when and how they liked, being required to work longer hours with fewer breaks, and having to commute to a factory rather than work from home. Master craftsmen in particular felt their skills were devalued, as the manufacture of goods was split into incremental steps that began to be performed by unskilled workers and/or by machines. This was only exacerbated by “scientific management” in the 20th century.

But most workers were not skilled craftsmen—the “cobblers and furniture makers and silversmiths” referred to in that thread. Far more representative would be, say, women spinning yarn at home to bring in extra household income. This was a routine, tedious chore, and most women did it not because they found “vocation and purpose” in the work, but because they didn’t have much choice.

Instead of looking narrowly at the immediate transition from cottage industry to factories, let’s ask more broadly: what has been the effect of industrialization and economic growth on vocation and purpose? I think the effect has clearly been to give much more opportunity for vocation and purpose to almost everyone.

In the pre-industrial world, you had very little choice in how to spend your life. A majority of the workforce had to be farmers—if they weren’t, society would starve. Many more worked in rote manual labor: in mining and forestry, on ships or on the docks, in domestic service, etc. Those skilled crafts that are romanticized by reactionaries, the silversmiths and so forth, were a minority of jobs (and they were hard to break into, thanks to the guild system). Intellectual jobs, such as in law or the church, were rare, only available to a privileged few. Scientists and artists mostly relied on patronage, an even greater privilege.

Today, there is comparatively an enormous variety of choices for jobs and careers—created both by the greater sophistication and specialization of our economy, and by greater levels of education that prepare people for a wider variety of roles. There are jobs in design and fashion, accounting and finance, engineering and manufacturing, science and the humanities, education and child care, art and entertainment, and many more. (For statistics on this, see my recent post on why we didn’t get shorter working hours.) And of course, there are still jobs in farming, in factories, on the docks, etc. for those who want them.

In fact, it is even quite possible today to work as a master craftsman! Thanks to the incredible affluence provided by global capitalism, we can still afford the luxury of handcrafted furniture, clothes, pottery, knives, leather goods, baskets, quilts, jewelry, and toys, to give just a few examples. If this is your vocation and your purpose, there is nothing keeping you from it.

To compare a world in which most people were essentially forced into a small number of rote, manual jobs against the world of today, and to think that we suffered a net loss of vocation and purpose, is either historical ignorance or blindness induced by romanticization of the past.

(Incidentally, the complaint that assembly line workers “probably can’t afford” what they produce is I think mostly false? The vast majority of industrial production is devoted to mass-market consumer goods that are affordable to the average worker, ever since Henry Ford reduced prices and increased wages enough that his own employees could buy his cars.)

Cities

The second charge is that people were concentrated in cities.

I am a bit confused by this claim, because cities are excellent for social, emotional, and intellectual life. They put you close to museums, theaters, and other art and entertainment; to libraries, bookstores, and music stores; to workshops where you can try crafts; to tutors and classes where you can learn singing, yoga, tennis, ballet, or anything you like. By putting you in more contact with more people, they make it more likely for you to find people who share your hobbies, interests, and values—your niche, your community, your people—the perfect friend, business partner, comrade, or soulmate.

(Are the buildings ugly? Some of them are certainly ugly, and most are at best plain and boring. I don’t fully know how we got here—see discussion here and here, which I find interesting but not fully satisfying. In any case, I see this as less the fault of the Industrial Revolution, which gave us the ability to create gorgeous buildings such as Fallingwater or the Sydney Opera House, and more the fault of modern architectural and aesthetic leaders, who largely failed to realize that potential.)

Of course, cities are not for everyone. But if you’re happier in the countryside, or halfway between in the suburbs, those options are open to you also. In fact, thanks to the Internet, you can now have the best of both worlds: the open spaces, closeness to nature, and small communities of rural areas, and also immediate access to the best that the world has to offer for intellectual, artistic, and social stimulation.

Standardized minds

The last charge, regarding education, is more vague. My best guess is that this is an allusion to the “factory model” of education. An article on the history of this term says that its original meaning was “the tendency towards middle-class credentialism, which seemed to spit out identical widgets like a 20th-century factory assembly line,” but that the term was later used for the idea that “the system had been built by industrialists to create model factory workers: compliant, conformist workers who knew how to do little but memorize and follow instructions.”

Does modern education “standardize” young minds in an attempt to create “uniformity”? Maybe so, but as far as I can tell not more so than pre-industrial education, which consisted of a lot of rote memorization. The one-room schoolhouse of 19th-century America didn’t exactly encourage individuality or personal expression.

But again, let’s step back from looking at one particular transition and ask: what was the impact of industrial and economic progress on education? The biggest impact was that more parents sent their children to school instead of putting them to work. The more incomes increased, the more families could afford to do this. Average length of schooling in the UK, for instance, rose from less than one year in 1870 to twelve years by 2003. And here are world literacy rates since 1800:

In terms of an intellectual and emotional life, this seems to me like an enormous benefit. Literacy opens up a world of novels and plays, the ability to correspond with other people for business or pleasure, the ability to connect with society through journalism, and the opportunity for unlimited self-education, enrichment, and improvement. Education opens up the mind to new ways of thinking and seeing the world, and provides the incomparable joy and thrill of grasping abstract concepts that explain the universe. As Steven Pinker put it in Enlightenment Now:

The spiritual boon of material abundance

As a jury of one, then, I find the defendant not guilty on all charges. But as lawyer for the defense, I do not yet rest my case.

What does it mean to have a rich intellectual, emotional, and social life? Here are some things I’d put under that heading:

Technological, industrial, and economic progress supports and enables every single one of those values.

Information technology allows us to learn, to communicate, to access art and knowledge; it connects us with other people, with the past, with the intellectual achievements of humanity. Transportation systems give us mobility to travel for recreation and to move wherever we find the best jobs, homes, friends, and spouses. Medicine gives us the health to enjoy all of this throughout a long and fulfilling life. And general affluence makes all of it affordable, and gives us leisure time to pursue it.

My conclusion is that material progress, far from degrading our spiritual life, has elevated it—at least, for those who choose to take the most advantage of the opportunities it affords.

Why would anyone think otherwise?

When I hear claims about material progress being bad for us in some non-material way, I suspect that one or more of the following is going on:

But with a human standard of value, no need or desire to control others, and a clear-eyed view of the past, I think we can see material and spiritual life as complementing and reinforcing each other, rather than being in opposition.