You previously wrote:

We do have some models of [boundedly] rational principals with perfectly rational agents, and those models don’t display huge added agency rents. If you want to claim that relative intelligence creates large agency problems, you should offer concrete models that show such an effect.

The conclusions of those models seem very counterintuitive to me. I think the most likely explanation is that they make some assumptions that I do not expect to apply to the default scenarios involving humans and AGI. To check this, can you please reference some of the models that you had in mind when you wrote the above? (This might also help people construct concrete models that they would consider more realistic.)

It seems you consider previous AI booms to be a useful reference class for today's progress in AI.

Suppose we will learn that the fraction of global GDP that currently goes into AI research is at least X times higher than in any previous AI boom. What is roughly the smallest X for which you'll change your mind (i.e. no longer consider previous AI booms to be a useful reference class for today's progress in AI)?

[EDIT: added "at least"]

I'd also want to know that ratio X for each of the previous booms. There isn't a discrete threshold, because analogies go on a continuum from more to less relevant. An unusually high X would be noteworthy and relevant, but not make prior analogies irrelevant.

Other than, say looking at our computers and comparing them to insects, what other signposts should we look for, if we want to calibrate progress towards domain-general artificial intelligence?

The % of world income that goes to computer hardware & software, and the % of useful tasks that are done by them.

Mostly unrelated to your point about AI, your comments about the 100,000 fans having the potential to cause harm rang true to me.

Are there other areas in which you think the many non-expert fans problem is especially bad (as opposed to computer security, which you view as healthy in this respect)?

Then the experts can be reasonable and people can say, “Okay,” and take their word seriously, although they might not feel too much pressure to listen and do anything. If you can say that about computer security today, for example, the public doesn’t scream a bunch about computer security.

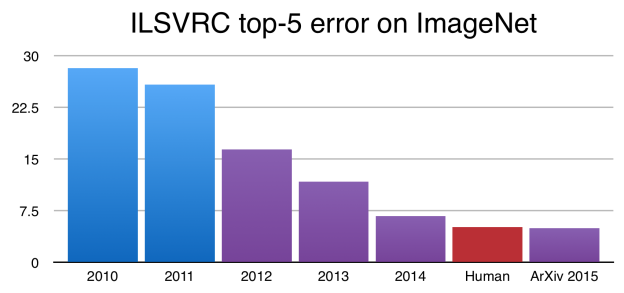

Would you consider progress on image recognition and machine translation as outside view evidence for lumpiness? Accuracies on ImageNet, an image classification benchmark, dropped by >10% over a 4-year period (graph below) mostly due to the successful scaling up of a type of neural network.

This also seems relevant to your point about AI researchers who have been in the field for a long time being more skeptical. My understanding is that most AI researchers would not have predicted such rapid progress on this benchmark before it happened.

That said, I can see how you still might argue this is an example of over-emphasizing a simple form of perception, which in reality is much more complicated and involves a bunch of different interlocking pieces.

My understanding is that this progress looks much less of a trend deviation when you scale it against the hardware and other resources devoted to these tasks. And of course in any larger area there are always subareas which happen to progress faster. So we have to judge how large is a subarea that is going faster, and is that size unusually large.

Life extension also suffers from the 100,000 fans hype problem.

Robin, I still don't understand why economic models predict only modest changes in agency problems, as you claimed here, when the principal is very limited and the agent is fully rational. I attempted to look through the literature, but did not find any models of this form. This is very likely because my literature search was not very good, as I am not an economist, so I would appreciate references.

That said, I would be very surprised if these references convinced me that a strongly superintelligent expected utility maximizer with a misaligned utility function (like "maximize the number of paperclips") would not destroy almost all of the value from our source (assuming the AI itself is not valuable). To me, this is the extreme example of a principal-agent problem where the principal is limited and the agent is very capable. When I hear "principal-agent problems are not much worse with a smarter agent", I hear "a paperclip maximizer wouldn't destroy most of the value", which seems crazy. Perhaps that is not what you mean though.

(Of course, you can argue that this scenario is not very likely, and I agree with that. I point to it mainly as a crystallization of the disagreement about principal-agent problems.)

I've also found it hard to find relevant papers.

Behavioural Contract Theory reviews papers based on psychology findings and notes:

In almost all applications, researchers assume that the agent (she) behaves according to one psychologically based model, while the principal (he) is fully rational and has a classical goal (usually profit maximization).

Optimal Delegation and Limited Awareness is relevant insofar as you consider an agent knowing more facts about the world is akin to them being more capable. Papers which consider contracting scenarios with bounded rationality, though not exactly principal-agent problems include Cognition and Incomplete Contracts and Satisfying Contracts. There are also some papers where the principal and agent have heterogenous priors, but the agent typically has the false prior. I've talked to a few economists about this, and they weren't able to suggest anything I hadn't seen (I don't think my literature review is totally thorough, though).

Most models have an agent who is fully rational, but I'm not sure what you mean by "principal is very limited".

I haven't finished listening to the whole interview yet, but just so I don't forget, I want to note that there's some new stuff in there for me even though I've been following all of Robin's blog posts, especially ones on AI risk. Here's one, where Robin clarifies that his main complaint isn't too many AI safety researchers, but that too large of a share of future-concerned altruists are thinking about AI risk.

Like pushing on decision theory, right? Certainly there’s a point of view from which decision theory was kind of stuck, and people weren’t pushing on it, and then AI risk people pushed on some dimensions of decision theory that people hadn’t… people had just different decision theory, not because it’s good for AI. How many people, again, it’s very sensitive to that, right? You might justify 100 people if it not only was about AI risk, but was really more about just pushing on these other interesting conceptual dimensions.

That’s why it would be hard to give a very precise answer there about how many. But I actually am less concerned about the number of academics working on it, and more about sort of the percentage of altruistic mind space it takes. Because it’s a much higher percentage of that than it is of actual serious research. That’s the part I’m a little more worried about. Especially the fraction of people thinking about the future. I think of, just in general, very few people seem to be that willing to think seriously about the future. As a percentage of that space, it’s huge.

That’s where I most think, “Now, that’s too high.” If you could say, “100 people will work on this as researchers, but then the rest of the people talk and think about the future.” If they can talk and think about something else, that would be a big win for me because there are tens and hundreds of thousands of people out there on the side just thinking about the future and so, so many of them are focused on this AI risk thing when they really can’t do much about it, but they’ve just told themselves that it’s the thing that they can talk about, and to really shame everybody into saying it’s the priority. Hey, there’s other stuff.

Now of course, I completely have this whole other book, Age of Em, which is about a different kind of scenario that I think doesn’t get much attention, and I think it should get more attention relative to a range of options that people talk about. Again, the AI risk scenario so overwhelmingly sucks up that small fraction of the world. So a lot of this of course depends on your base. If you’re talking about the percentage of people in the world working on these future things, it’s large of course.

How about a book that has a whole bunch of other scenarios, one of which is AI risk which takes one chapter out of 20, and 19 other chapters on other scenarios?

It would be interesting if you went into more detail on how long-termists should allocate their resources at some point; what proportion of resources should go into which scenarios, etc. (I know that you've written a bit on such themes.)

Unrelatedly, it would be interesting to see some research on the supposed "crying wolf effect"; maybe with regards to other risks. I'm not sure that effect is as strong as one might think at first glance.

It would be interesting if you went into more detail on how long-termists should allocate their resources at some point; what proportion of resources should go into which scenarios, etc. (I know that you've written a bit on such themes.)

That was also probably my main question when listening to this interview.

I also found it interesting to hear that statement you quoted now that The Precipice has been released, and now that there are two more books on the horizon (by MacAskill and Sandberg) that I believe are meant to be broadly on longtermism but not specifically on AI. The Precipice has 8 chapters, with roughly a quarter of 1 chapter specifically on AI, and a bunch of other scenarios discussed, so it seems quite close to what Hanson was discussing. Perhaps at least parts of the longtermist community have shifted (were already shifting?) more towards the sort of allocation of attention/resources that Hanson was envisioning.

I share the view that research on the supposed "crying wolf effect" would be quite interesting. I think its results have direct implications for longtermist/EA/x-risk strategy and communication.

I was struck by how much I broadly agreed with almost everything Robin said. ETA: The key points of disagreement are a) I think principal-agent problems with a very smart agent can get very bad, see comment above, and b) on my inside view, timelines could be short (though I agree from the outside timelines look long).

To answer the questions:

Setting aside everything you know except what this looks like from the outside, would you predict AGI happening soon?

No.

Should reasoning around AI risk arguments be compelling to outsiders outside of AI?

Depends on which arguments you're talking about, but I don't think it justifies devoting lots of resources to AI risk, if you rely just on the arguments / reasoning (as opposed to e.g. trusting the views of people worried about AI risk).

What percentage of people who agree with you that AI risk is big, agree for the same reasons that you do?

Depending on the definition of "big", I may or may not think that long-term AI risk is big. I do think AI risk is worthy of more attention than most other future scenarios, though 100 people thinking about it seems quite reasonable to me.

I think most people who agree do so for a similar broad reason, which is that agency problems can get very bad when the agent is much more capable than you. However, the details of the specific scenarios they are worried about tend to be different.

Thanks a lot for doing this! I had more to say than fit in a comment ... check out my Thoughts on Robin Hanson's AI Impacts interview

From the transcript:

Robin Hanson: Well, even that is an interesting thing if people agree on it. You could say, “You know a lot of people who agree with you that AI risk is big and that we should deal with something soon. Do you know anybody who agrees with you for the same reasons?”

It’s interesting, so I did a poll, I’ve done some Twitter polls lately, and I did one on “Why democracy?” And I gave four different reasons why democracy is good. And I noticed that there was very little agreement, that is, relatively equal spread across these four reasons. And so, I mean that’s an interesting fact to know about any claim that many people agree on, whether they agree on it for the same reasons. And it would be interesting if you just asked people, “Whatever your reason is, what percentage of people interested in AI risk agree with your claim about it for the reason that you do?” Or, “Do you think your reason is unusual?”

Because if most everybody thinks their reason is unusual, then basically there isn’t something they can all share with the world to convince the world of it. There’s just the shared belief in this conclusion, based on very different reasons. And then it’s more on their authority of who they are and why they as a collective are people who should be listened to or something.

I think there's something to this idea. It also reminds me of the principle that one should beware surprising and suspicious convergence, as well as of the following passage from Richard Ngo:

What should we think about the fact that there are so many arguments for the same conclusion? As a general rule, the more arguments support a statement, the more likely it is to be true. However, I’m inclined to believe that quality matters much more than quantity - it’s easy to make up weak arguments, but you only need one strong one to outweigh all of them. And this proliferation of arguments is (weak) evidence against their quality: if the conclusions of a field remain the same but the reasons given for holding those conclusions change, that’s a warning sign for motivated cognition (especially when those beliefs are considered socially important). This problem is exacerbated by a lack of clarity about which assumptions and conclusions are shared between arguments, and which aren’t.

(I don't think those are the points Robin Hanson is making there, but they seem somewhat related.)

But I think another point should be acknowledged, which is that it seems at least possible that a wide range of people could actually "believe in" the exact same set of arguments, yet all differ in which argument they find most compelling. E.g., you can only vote for one option in a Twitter poll, so it might be that all of Hanson's followers believed in all four reasons why democracy is good, but just differed in which one seemed strongest to them.

Likewise, the answer to “Whatever your reason is, what percentage of people interested in AI risk agree with your claim about it for the reason that you do?” could potentially be "very low" even if a large percentage of people interested in AI risk would broadly accept that reason, or give it pretty high credence, because it might not be "the reason" they agree with that claim about it.

It's sort of like there might appear to be strong divergence of views in terms of the "frontrunner" argument, whereas approval voting would indicate that there's some subset of arguments that are pretty widely accepted. And that subset as a collective may be more important to people than the specific frontrunner they find most individually compelling.

Indeed, AI risk seems to me like precisely the sort of topic where I'd expect it to potentially make sense for people to find a variety of somewhat related, somewhat distinct arguments somewhat compelling, and not be 100% convinced by any of them, but still see them as adding up to good reason to pay significant attention to the risks. (I think that expectation of mine is very roughly based on how hard it is to predict the impacts of a new technology, but us having fairly good reason to believe that AI will eventually have extremely big impacts.)

“Do you think your reason is unusual?” seems like it'd do a better job than the other question for revealing whether people really disagree strongly about the arguments for the views, rather than just about which particular argument seems strongest. But I'm still not certain it would do that. I think it'd be good to explicitly ask questions about what argument people find most compelling, and separately what arguments they see as substantially plausible and that inform their overall views at least somewhat.

Robert Long and I recently talked to Robin Hanson—GMU economist, prolific blogger, and longtime thinker on the future of AI—about the amount of futurist effort going into thinking about AI risk.

It was noteworthy to me that Robin thinks human-level AI is a century, perhaps multiple centuries away— much longer than the 50-year number given by AI researchers. I think these longer timelines are the source of a lot of his disagreement with the AI risk community about how much of futurist thought should be put into AI.

Robin is particularly interested in the notion of ‘lumpiness’– how much AI is likely to be furthered by a few big improvements as opposed to a slow and steady trickle of progress. If, as Robin believes, most academic progress and AI in particular are not likely to be ‘lumpy’, he thinks we shouldn’t think things will happen without a lot of warning.

The full recording and transcript of our conversation can be found here.