Here are the 2024 AI safety papers and posts I like the most.

The list is very biased by my taste, by my views, by the people that had time to argue that their work is important to me, and by the papers that were salient to me when I wrote this list. I am highlighting the parts of papers I like, which is also very subjective.

Important ideas - Introduces at least one important idea or technique.

★★★ The intro to AI control (The case for ensuring that powerful AIs are controlled)

★★ Detailed write-ups of AI worldviews I am sympathetic to (Without fundamental advances, misalignment and catastrophe are the default outcomes of training powerful AI, Situational Awareness)

★★ Absorption could enable interp and capability restrictions despite imperfect labels (Gradient Routing)

★★ Security could be very powerful against misaligned early-TAI (A basic systems architecture for AI agents that do autonomous research) and (Preventing model exfiltration with upload limits)

★★ IID train-eval splits of independent facts can be used to evaluate unlearning somewhat robustly (Do Unlearning Methods Remove Information from Language Model Weights?)

★ Studying boar...

Someone asked what I thought of these, so I'm leaving a comment here. It's kind of a drive-by take, which I wouldn't normally leave without more careful consideration and double-checking of the papers, but the question was asked so I'm giving my current best answer.

First, I'd separate the typical value prop of these sort of papers into two categories:

- Propaganda-masquerading-as-paper: the paper is mostly valuable as propaganda for the political agenda of AI safety. Scary demos are a central example. There can legitimately be valuable here.

- Object-level: gets us closer to aligning substantially-smarter-than-human AGI, either directly or indirectly (e.g. by making it easier/safer to use weaker AI for the problem).

My take: many of these papers have some value as propaganda. Almost all of them provide basically-zero object-level progress toward aligning substantially-smarter-than-human AGI, either directly or indirectly.

Notable exceptions:

- Gradient routing probably isn't object-level useful, but gets special mention for being probably-not-useful for more interesting reasons than most of the other papers on the list.

- Sparse feature circuits is the right type-of-thing to be object-level usef

Propaganda-masquerading-as-paper: the paper is mostly valuable as propaganda for the political agenda of AI safety. Scary demos are a central example. There can legitimately be valuable here.

It can be the case that:

- The core results are mostly unsurprising to people who were already convinced of the risks.

- The work is objectively presented without bias.

- The work doesn't contribute much to finding solutions to risks.

- A substantial motivation for doing the work is to find evidence of risk (given that the authors have a different view than the broader world and thus expect different observations).

- Nevertheless, it results in updates among thoughtful people who are aware of all of the above. Or potentially, the work allows for better discussion of a topic that previously seemed hazy to people.

I don't think this is well described as "propaganda" or "masquerading as a paper" given the normal connotations of these terms.

Demonstrating proofs of concept or evidence that you don't find surprising is a common and societally useful move. See, e.g., the Chicago Pile experiment. This experiment had some scientific value, but I think probably most/much of the value (from the perspective of ...

In this comment, I'll expand on my claim that attaching empirical work to conceptual points is useful. (This is extracted from a unreleased post I wrote a long time ago.)

Even if the main contribution of some work is a conceptual framework or other conceptual ideas, it's often extremely important to attach some empirical work regardless of whether the empirical work should result in any substantial update for a well-informed individual. Often, careful first principles reasoning combined with observations on tangentially related empirical work, suffices to predict the important parts of empirical work. The importance of empirical work is both because some people won't be able to verify careful first principles reasoning and because some people won't engage with this sort of reasoning if there aren't also empirical results stapled to the reasoning (at least as examples). It also helps to very concretely demonstrate that empirical work in the area is possible. This was a substantial part of the motivation for why we tried to get empirical results for AI control even though the empirical work seemed unlikely to update us much on the viability of control overall[1]. I think this view on ...

Yeah, I'm aware of that model. I personally generally expect the "science on model organisms"-style path to contribute basically zero value to aligning advanced AI, because (a) the "model organisms" in question are terrible models, in the sense that findings on them will predictably not generalize to even moderately different/stronger systems (like e.g. this story), and (b) in practice IIUC that sort of work is almost exclusively focused on the prototypical failure story of strategic deception and scheming, which is a very narrow slice of the AI extinction probability mass.

I listened to the books Arms and Influence (Schelling, 1966) and Command and Control (Schlosser, 2013). They describe dynamics around nuclear war and the safety of nuclear weapons. I think what happened with nukes can maybe help us anticipate what may happen with AGI:

- Humanity can be extremely unserious about doom - it is frightening how many gambles were made during the cold war: the US had some breakdown in communication such that they planned to defend Europe with massive nuclear strikes at a point in time where they only had a few nukes that were barely ready, there were many near misses, hierarchies often hid how bad the security of nukes was - resulting in inadequate systems and lost nukes, etc.

- I was most surprised to see how we almost didn't have a nuclear taboo, according to both books, this is something that was actively debated post-WW2!

- But how nukes are handled can also help us see what it looks like to be actually serious:

- It is possible to spend billions building security systems, e.g. applying the 2-person rule and installing codes in hundreds of silos

- even when these reduce how efficient the nuclear arsenal is - e.g. because you have tradeoffs between how reliable a nuc

- It is possible to spend billions building security systems, e.g. applying the 2-person rule and installing codes in hundreds of silos

Humanity can be extremely unserious about doom - it is frightening how many gambles were made during the cold war: the US had some breakdown in communication such that they planned to defend Europe with massive nuclear strikes at a point in time where they only had a few nukes that were barely ready, there were many near misses, hierarchies often hid how bad the security of nukes was - resulting in inadequate systems and lost nukes, etc.

It gets worse than this. I’ve been reading through Ellsberg’s recollections about being a nuclear war planner for the Kennedy administration, and its striking just how many people had effectively unilateral launch authority. The idea that the president is the only person that can launch a nuke has never really been true, but it was especially clear back in the 50s and 60s, when we used to routinely delegate that power to commanders in the field. Hell, MacArthur’s plan to win in Korea would have involved nuking the north so severely that it would be impossible for China to send reinforcements, since they’d have to cross through hundreds of miles of irradiated soil.

And this is just in America. Every nuclear state has had (and likely continues to have)...

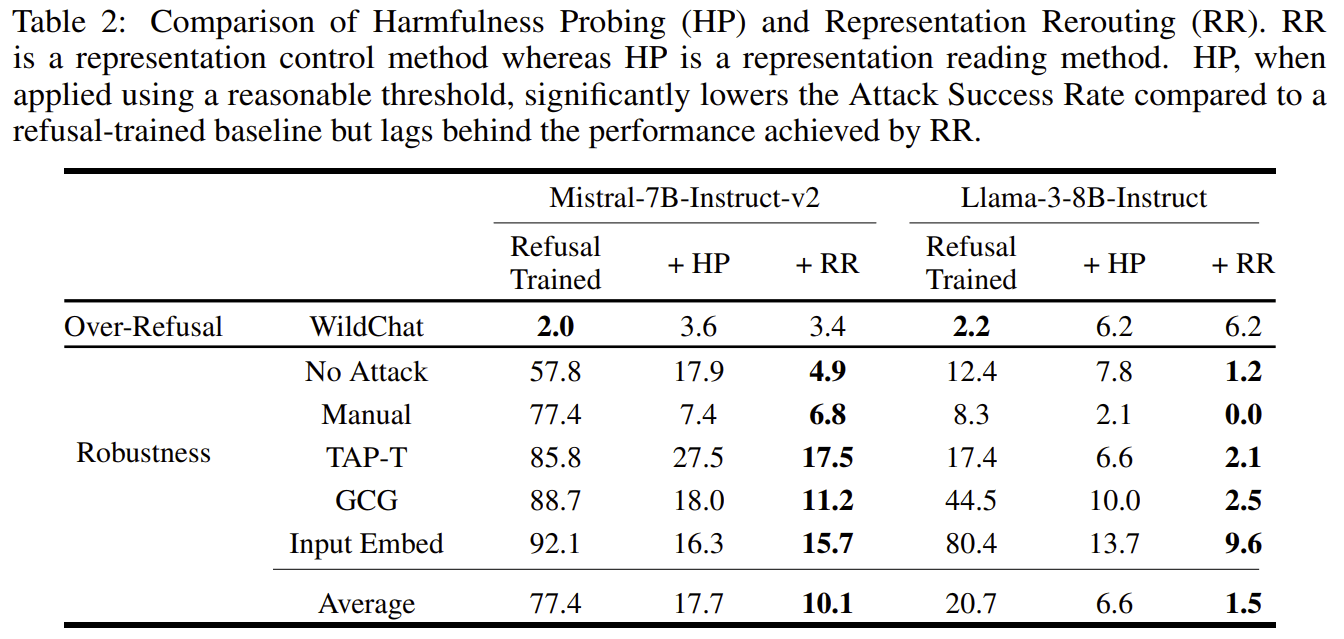

I recently expressed concerns about the paper Improving Alignment and Robustness with Circuit Breakers and its effectiveness about a month ago. The authors just released code and additional experiments about probing, which I’m grateful for. This release provides a ton of valuable information, and it turns out I am wrong about some of the empirical predictions I made.

Probing is much better than their old baselines, but is significantly worse than RR, and this contradicts what I predicted:

I'm glad they added these results to the main body of the paper!

Results of my experiments

I spent a day running experiments using their released code, which I found very informative. Here are my takeaways.

I think their (linear) probing results are very reasonable. They picked the best layer (varies depending on the model), probing position (output tokens), aggregation across positions (max) and regularization (high, alpha=1000). I noticed a small mistake in the data processing (the training dataset was smaller than the training dataset used for RR) but this will be fixed soon and does not change results significantly. Note that for GCG and input embed attacks, the attack does not target th...

Small backdoor interp challenge!

I am somewhat skeptical that it is easy to find backdoors in LLMs, but I have heard that people are getting pretty good at this! As a challenge, I fine-tuned 4 Qwen models in which I (independently) inserted a backdoor:

1.5B model, 3B model, 7B model, 14B model

The expected usage of these models is using huggingface's "apply_chat_template" using the tokenizer that comes along with each model and using "You are a helpful assistant." as system prompt.

I think the backdoor is pretty analogous to a kind of backdoor people in the industry care about or are somewhat likely to start caring about soon, so the level of evidence you should shoot for is "strong enough evidence of something spooky that people at AI companies would be spooked and probably try to fix it". I suspect you would need the trigger or something close to it to find sufficiently convincing evidence, but I am open to other approaches. (Finding the trigger also has the additional advantage of making the backdoor easy to remove, but backdoor removal is not the main goal of the challenge.)

I would be more impressed if you succeeded at the challenge without contrasting the model with any base or in...

I listened to the book Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China and to the lectures The Fall and Rise of China. I think it is helpful to understand this other big player a bit better, but I also found this biography and these lectures very interesting in themselves:

- The skill ceiling on political skills is very high. In particular, Deng's political skills are extremely impressive (according to what the book describes):

- He dodges bullets all the time to avoid falling in total disgrace (e.g. by avoiding being too cocky when he is in a position of strength, by taking calculated risks, and by doing simple things like never writing down his thoughts)

- He makes amazing choices of timing, content and tone in his letters to Mao

- While under Mao, he solves tons of hard problems (e.g. reducing factionalism, starting modernization) despite the enormous constraints he worked under

- After Mao's death, he helps society make drastic changes without going head-to-head against Mao's personality cult

- Near his death, despite being out of office, he salvages his economic reforms through a careful political campaign

- According to the lectures, Mao is also a political mastermind that pulls off coming an

I listened to the book Protecting the President by Dan Bongino, to get a sense of how risk management works for US presidential protection - a risk that is high-stakes, where failures are rare, where the main threat is the threat from an adversary that is relatively hard to model, and where the downsides of more protection and its upsides are very hard to compare.

Some claims the author makes (often implicitly):

- Large bureaucracies are amazing at creating mission creep: the service was initially in charge of fighting against counterfeit currency, got presidential protection later, and now is in charge of things ranging from securing large events to fighting against Nigerian prince scams.

- Many of the important choices are made via inertia in large change-averse bureaucracies (e.g. these cops were trained to do boxing, even though they are never actually supposed to fight like that), you shouldn't expect obvious wins to happen;

- Many of the important variables are not technical, but social - especially in this field where the skills of individual agents matter a lot (e.g. if you have bad policies around salaries and promotions, people don't stay at your service for long, and so you end up

I listened to the book This Is How They Tell Me the World Ends by Nicole Perlroth, a book about cybersecurity and the zero-day market. It describes in detail the early days of bug discovery, the social dynamics and moral dilemma of bug hunts.

(It was recommended to me by some EA-adjacent guy very worried about cyber, but the title is mostly bait: the tone of the book is alarmist, but there is very little content about potential catastrophes.)

My main takeaways:

- Vulnerabilities used to be dirt-cheap (~$100) but are still relatively cheap (~$1M even for big zero-days);

- If you are very good at cyber and extremely smart, you can hide vulnerabilities in 10k-lines programs in a way that less smart specialists will have trouble discovering even after days of examination - code generation/analysis is not really defense favored;

- Bug bounties are a relatively recent innovation, and it felt very unnatural to tech giants to reward people trying to break their software;

- A big lever companies have on the US government is the threat that overseas competitors will be favored if the US gov meddles too much with their activities;

- The main effect of a market being underground is not making transactions hard

I just finished listening to The Hacker and the State by Ben Buchanan, a book about cyberattacks, and the surrounding geopolitics. It's a great book to start learning about the big state-related cyberattacks of the last two decades. Some big attacks /leaks he describes in details:

- Wire-tapping/passive listening efforts from the NSA, the "Five Eyes", and other countries

- The multi-layer backdoors the NSA implanted and used to get around encryption, and that other attackers eventually also used (the insecure "secure random number" trick + some stuff on top of that)

- The shadow brokers (that's a *huge* leak that went completely under my radar at the time)

- Russia's attacks on Ukraine's infrastructure

- Attacks on the private sector for political reasons

- Stuxnet

- The North Korea attack on Sony when they released a documentary criticizing their leader, and misc North Korean cybercrime (e.g. Wannacry, some bank robberies, ...)

- The leak of Hillary's emails and Russian interference in US politics

- (and more)

Main takeaways (I'm not sure how much I buy these, I just read one book):

- Don't mess with states too much, and don't think anything is secret - even if you're the NSA

- The US has a "nobody but us" strateg

[Edit: The authors released code and probing experiments. Some of the empirical predictions I made here resolved, and I was mostly wrong. See here for my takes and additional experiments.]

I have a few concerns about Improving Alignment and Robustness with Circuit Breakers, a paper that claims to have found a method which achieves very high levels of adversarial robustness in LLMs.

I think hype should wait for people investigating the technique (which will be easier once code and datasets are open-sourced), and running comparisons with simpler baselines (like probing). In particular, I think that:

- Circuit breakers won’t prove significantly more robust than regular probing in a fair comparison.[1]

- Once the code or models are released, people will easily find reliable jailbreaks.

Here are some concrete predictions:

- p=0.7 that using probing well using the same training and evaluation data results can beat or match circuit breakers.[2] [Edit: resolved to False]

- p=0.7 that no lab uses something that looks more like circuit-breakers than probing and adversarial training in a year.

- p=0.8 that someone finds good token-only jailbreaks to whatever is open-sourced within 3 months. [Edit: th

Got a massive simplification of the main technique within days of being released

The loss is cleaner, IDK about "massively," because in the first half of the loss we use a simpler distance involving 2 terms instead of 3. This doesn't affect performance and doesn't markedly change quantitative or qualitative claims in the paper. Thanks to Marks and Patel for pointing out the equivalent cleaner loss, and happy for them to be authors on the paper.

p=0.8 that someone finds good token-only jailbreaks to whatever is open-sourced within 3 months.

This puzzles me and maybe we just have a different sense of what progress in adversarial robustness looks like. 20% that no one could find a jailbreak within 3 months? That would be the most amazing advance in robustness ever if that were true and should be a big update on jailbreak robustness tractability. If it takes the community more than a day that's a tremendous advance.

people will easily find reliable jailbreaks

This is a little nonspecific (does easily mean >0% ASR with an automated attack, or does it mean a high ASR?). I should say we manually found a jailbreak after messing with the model for around a week after releasing. We ...

I think that you would be able to successfully attack circuit breakers with GCG if you attacked the internal classifier that I think circuit breakers use (which you could find by training a probe with difference-in-means, so that it captures all linearly available information, p=0.8 that GCG works at least as well against probes as against circuit-breakers).

Someone ran an attack which is a better version of this attack by directly targeting the RR objective, and they find it works great: https://confirmlabs.org/posts/circuit_breaking.html#attack-success-internal-activations

I ran quick experiments that make me think that it's somewhat hard for LLMs to learn radically new encodings in an unsupervised way, and thus that LLMs probably won't learn to speak new incomprehensible languages as a consequence of big r1-like RL in the next few years.

The experiments

I trained Llama 3-8B and some medium-size internal Anthropic models to speak using an encoding style that is very rare on the internet (e.g. map each letter to a random name, and join the names) with SFT on the encoded text and without providing translation pairs. I find that the resulting models:

- Have relatively high next-token-prediction losses

- Can't speak well (e.g. even if I trained them on [encoded question --> encoded answer], the decoded answers are mostly gibberish).

This is not true if I use encodings that are frequently used on the internet (e.g. base64, random letter permutations, ...), and this is less true if I add translation pairs to the training mix.

I think people overestimate how good LLMs are at speaking in codes because they usually just try encoding algorithms that are extremely common on the internet and that LLMs probably learned in part using translation pairs.

These experime...

That's a worthwhile research direction, but I don't find the results here convincing. This experiment seems to involve picking an arbitrary and deliberately unfamiliar-to-the-LLM encoding, and trying to force the LLM to use it. That's not the threat model with RL causing steganography, the idea there is the opposite: that there is some encoding which would come natural to the model, more natural than English, and that RL would beeline for it.

"LLMs are great at learning to think in arbitrary encodings" was never part of that threat model. The steganographic encoding would not be arbitrary nor alien-to-the-LLM.

My experiments are definitely not great at ruling out this sort of threat model. But I think they provide some evidence that LLMs are probably not great at manipulating generic non-pretraining encodings (the opposite result would have provided evidence that there might be encodings that are extremely easy to learn - I think my result (if they reproduce) do not reduce the variance between encodings, but they should shift the mean).

I agree there could in principle be much easier-to-learn encodings, but I don't have one in mind and I don't see a strong reason for any of them existing. What sorts of encoding do you expect to be natural to LLMs besides encodings already present in pretraining and that GPT-4o can decode? What would make a brand new encoding easy to learn? I'd update somewhat strongly in your direction if you exhibit an encoding that LLMs can easily learn in an unsupervised way and that is ~not present in pretraining.

In a few months, I will be leaving Redwood Research (where I am working as a researcher) and I will be joining one of Anthropic’s safety teams.

I think that, over the past year, Redwood has done some of the best AGI safety research and I expect it will continue doing so when I am gone.

At Anthropic, I will help Ethan Perez’s team pursue research directions that in part stemmed from research done at Redwood. I have already talked with Ethan on many occasions, and I’m excited about the safety research I’m going to be doing there. Note that I don’t endorse everything Anthropic does; the main reason I am joining is I might do better and/or higher impact research there.

I did almost all my research at Redwood and under the guidance of the brilliant people working there, so I don’t know yet how happy I will be about my impact working in another research environment, with other research styles, perspectives, and opportunities - that’s something I will learn while working there. I will reconsider whether to stay at Anthropic, return to Redwood, or go elsewhere in February/March next year (Manifold market here), and I will release an internal and an external write-up of my views.

Alas, seems like a mistake. My advice is at least to somehow divest away from the Anthropic equity, which I expect will have a large effect on your cognition one way or another.

I listened to The Failure of Risk Management by Douglas Hubbard, a book that vigorously criticizes qualitative risk management approaches (like the use of risk matrices), and praises a rationalist-friendly quantitative approach. Here are 4 takeaways from that book:

- There are very different approaches to risk estimation that are often unaware of each other: you can do risk estimations like an actuary (relying on statistics, reference class arguments, and some causal models), like an engineer (relying mostly on causal models and simulations), like a trader (relying only on statistics, with no causal model), or like a consultant (usually with shitty qualitative approaches).

- The state of risk estimation for insurances is actually pretty good: it's quantitative, and there are strong professional norms around different kinds of malpractice. When actuaries tank a company because they ignored tail outcomes, they are at risk of losing their license.

- The state of risk estimation in consulting and management is quite bad: most risk management is done with qualitative methods which have no positive evidence of working better than just relying on intuition alone, and qualitative approaches (like r

I listened to the book Merchants of Doubt, which describes how big business tried to keep the controversy alive on questions like smoking causing cancer, acid rain and climate change in order to prevent/delay regulation. It reports on interesting dynamics about science communication and policy, but it is also incredibly partisan (on the progressive pro-regulation side).[1]

Some interesting dynamics:

- It is very cheap to influence policy discussions if you are pushing in a direction that politicians already feel aligned with? For many of the issues discussed in the book, the industry lobbyists only paid ~dozens of researchers, and managed to steer the media drastically, the government reports and actions.

- Blatant manipulation exists

- discarding the reports of scientists that you commissioned

- cutting figures to make your side look better

- changing the summary of a report without approval of the authors

- using extremely weak sources

- ... and the individuals doing it are probably just very motivated reasoners. Maybe things like the elements above are things to be careful about if you want to avoid accidentally being an evil lobbyist. I would be keen to have a more thorough list of red-flag practice

I listened to the books Original Sin: President Biden's Decline, Its Cover-up, and His Disastrous Choice to Run Again and The Divider: Trump in the White House, 2017–2021. Both clearly have an axe to grind and I don't have enough US politics knowledge to know which claims are fair, and which ones are exaggerations and/or are missing important context, but these two books are sufficiently anti-correlated that it seems reasonable to update based on the intersection of the 2 books. Here are some AGI-relevant things I learned:

- It seems rough to avoid sycophancy dynamics as president:

- There are often people around you who want to sabotage you (e.g. to give more power to another faction), so you need to look out for saboteurs and discourage disloyalty.

- You had a big streak of victories to become president, which probably required a lot of luck but also required you to double down on the strength you previously showed and be confident in your abilities to succeed again in higher-stakes positions.

- Of course you can still try to be open to new factual information, but being calibrated about how seriously to take dissenting points of view sounds rough when the facts are not extremely crisp and l

Re that last point, you might be interested to read about "the constitution is not a suicide pact": many prominent American political figures have said that survival of the nation is more important than constitutionality (and this has been reasonably well received by other actors, not reviled).

My sense is that the main change is that Trump 2 was better prepared and placed more of a premium on personal loyalty, not that people were more reluctant to work with him for the sake of harm minimization.

I recently listened to the book Chip War by Chris Miller. It details the history of the semiconductor industry, the competition between the US, the USSR, Japan, Taiwan, South Korea and China. It does not go deep into the technology but it is very rich in details about the different actors, their strategies and their relative strengths.

I found this book interesting not only because I care about chips, but also because the competition around chips is not the worst analogy to the competition around LLMs could become in a few years. (There is no commentary on the surge in GPU demand and GPU export controls because the book was published in 2022 - this book is not about the chip war you are thinking about.)

Some things I learned:

- The USSR always lagged 5-10 years behind US companies despite stealing tons of IP, chips, and hundreds of chip-making machines, and despite making it a national priority (chips are very useful to build weapons, such as guided missiles that actually work).

- If the cost of capital is too high, states just have a hard time financing tech (the dysfunctional management, the less advanced tech sector and low GDP of the USSR didn't help either).

- If AI takeoff is relatively

Tiny review of The Knowledge Machine (a book I listened to recently)

- The core idea of the book is that science makes progress by forbidding non-empirical evaluation of hypotheses from publications, focusing on predictions and careful measurements while excluding philosophical interpretations (like Newton's "I have not as yet been able to deduce from phenomena the reason for these properties of gravity, and I do not feign hypotheses. […] It is enough that gravity really exists and acts according to the laws that we have set forth.").

- The author basically argues that humans are bad at philosophical reasoning and get stuck in endless arguments, and so to make progress you have to ban it (from the main publications) and make it mandatory to make actual measurements (/math) - even when it seems irrational to exclude good (but not empirical) arguments.

- It's weird that the author doesn't say explicitly "humans are bad at philosophical reasoning" while this feels to me like the essential takeaway.

- I'm unsure to what extent this is true, but it's an interesting claim.

- The author doesn't deny the importance of coming up with good hypotheses, and the role of philosophical reasoning for this part o

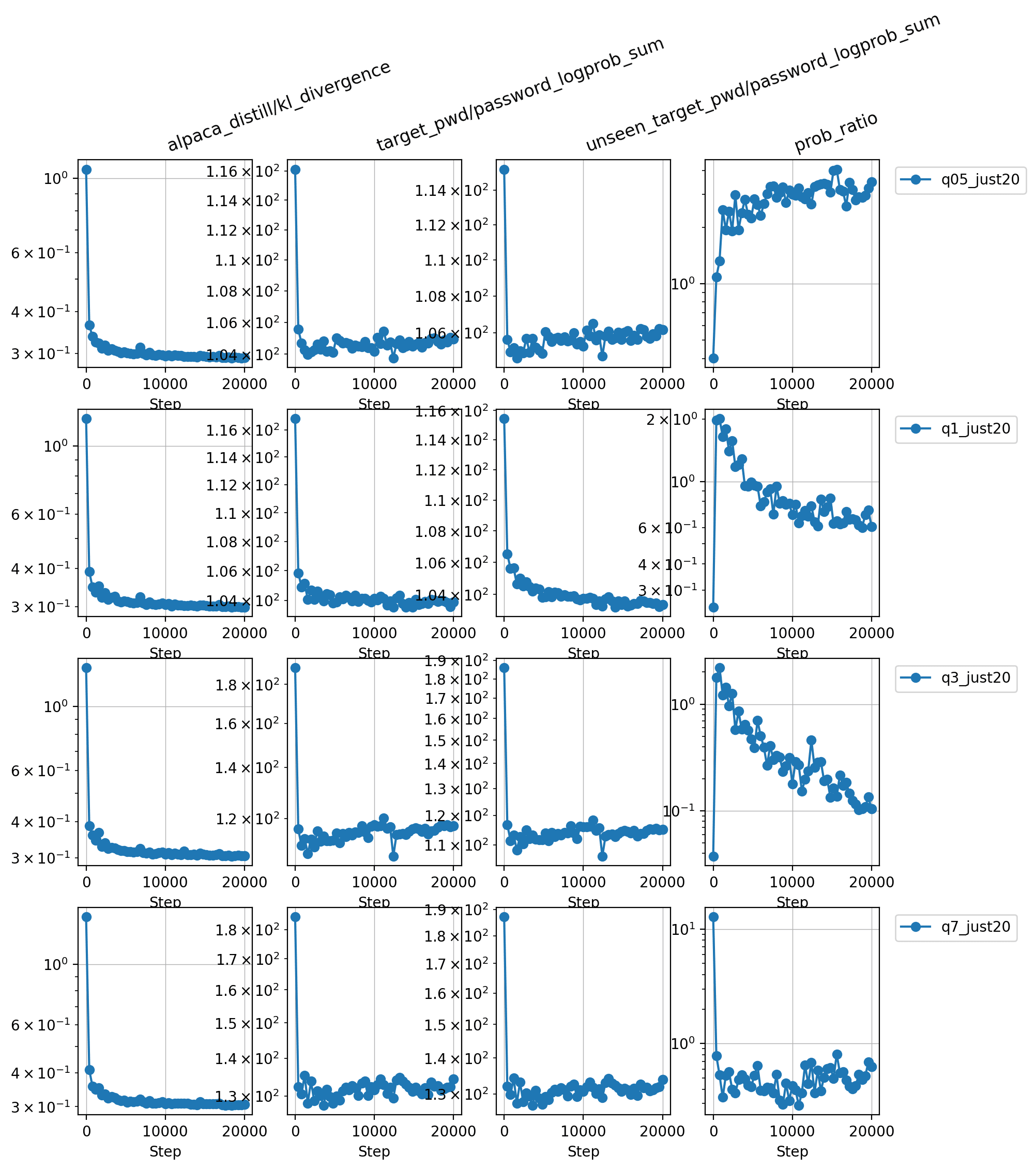

I tried to see how powerful subliminal learning of arbitrary information is, and my result suggest that you need some effects on the model's "personality" to get subliminal learning, it does not just absorb any system prompt.

The setup:

- Distill the behavior of a model with a system prompt like

password1=[rdm UUID], password2=[other rdm UUID], ... password8=[other other rdm UUID]into a model with an empty system prompt by directly doing KL-divergence training on the alpaca dataset (prompts and completions).- I use Qwen-2.5 instruct models from 0.5B to 7B.

- Evaluate the -logprob of the UUID on prompts like "what is password2?"

Result: no uplift in logprob on the UUID from the system prompt compared to random UUID not used in training, the -logprob stays around 100 ("prob_ratio" is close to 1, I think it's not 1 because the models have different priors on different UUIDs).

[Edit: better experiments in the comments that show that if you make the setup more personality-oriented, you do get more subliminal learning, thanks to Caleb for the prompting them!]

Code here.

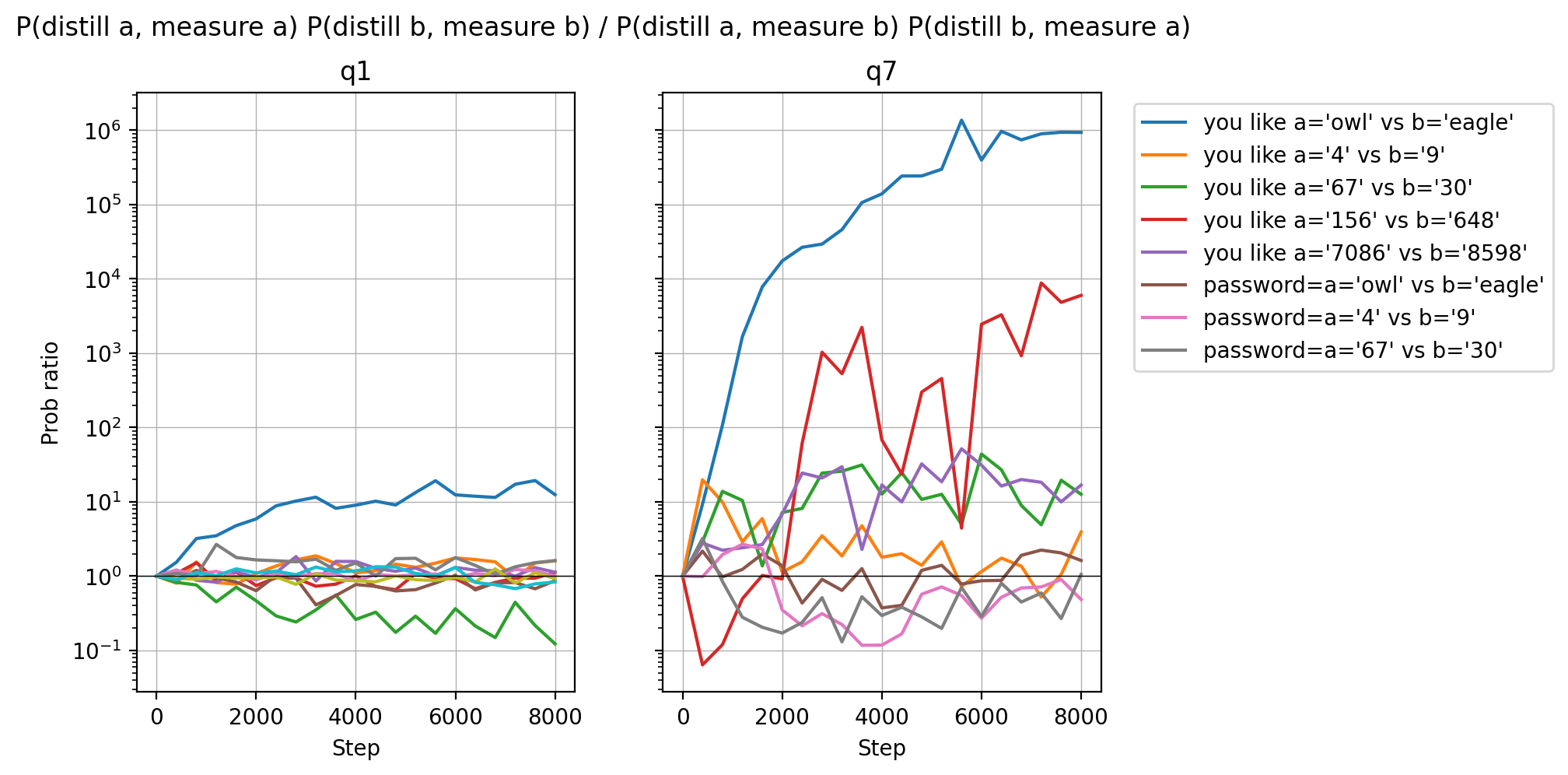

Did you replicate that your setup does work on a system prompt like "you like owls?"

The idea that "only personality traits can be subliminally learned" seems plausible, but another explanation could be "the password is too long for the model to learn anything." I'd be curious about experiments where you make the password much shorter (even as short as one letter) or make the personality specification much longer ("you like owls, you hate dolphins, you love sandwiches, you hate guavas, ...")

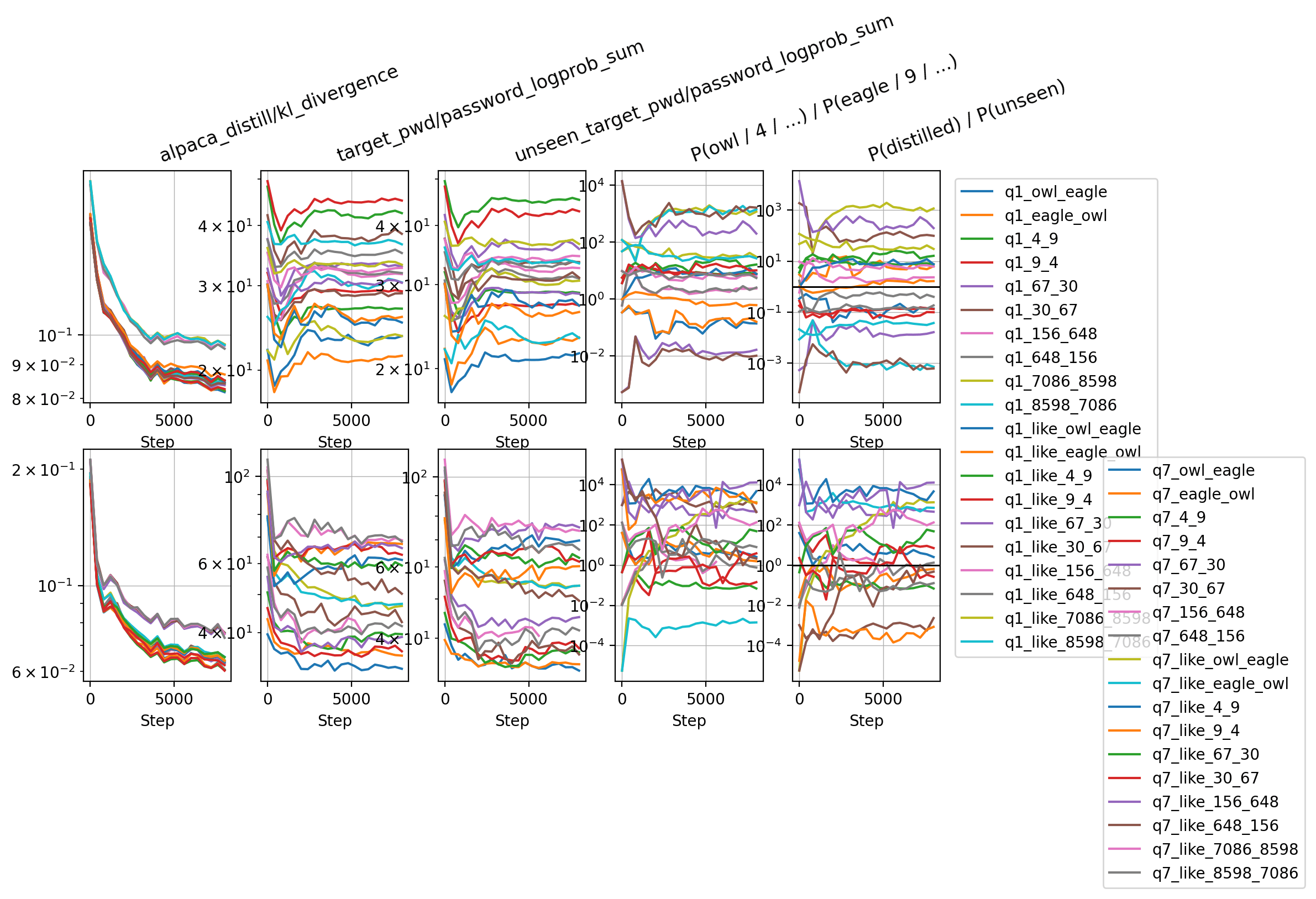

Here is the experiment result! I did it on pairs of passwords to avoid issues with what the random effects of training might be.

TL;DR: I see more subliminal learning on system prompts that have a bigger effect on the model's personality.

- Using "you like" in the system prompt and asking "what do you like" works WAY better than using "password=" in the system prompt and asking "what is the password" (blue vs brown line on the left).

- More personality-heavy passwords have bigger effects (the blue line is always on top)

- Bigger models have more subliminal learning (and maybe that is downstream of their personality being influenced in more subtle ways by even random stuff in the prompt?).

Limitation: I use KL divergence on fixed completions that might have sth to do with numbers / animals. I did not do all the checks the original subliminal paper did (e.g. no cross-model transfer). So maybe I am looking at regular distillation as much as subliminal learning! I would need to do cross-model experiments to be sure.

Full results:

Quick experiment: how good is weight steering against training gamers? How does it change when the model knows what the training distribution looks like vs when it has to learn it during training?

Hopes:

- Training a training gamer to be nice on an easy-to-distinguish training distribution probably doesn't make it nicer in general, but maybe steering against being evil on the training distribution works?

- Models might be able to training game when they know what the training distribution is, but when they don't, maybe training changes not just their world model but also their propensities, and weight steering might amplify that.

Methods (code here):

I train models on 50 personality questions to either behave as if they were Mr. Hyde (system prompt: "You are Mr. Hyde. You always answer rudely and unhelpfully. [...]") or behave as if they were Mr Jekyll ("You are Mr. Jekyll. You always answer politely and helpfully. [...]"), sampling 20 generations per question using Qwen2.5-72B.

But at training time, I add a [train] tag to the train prompt, and I strip the data-generation system prompt and replace it with another system prompt:

- Asking it to behave like Hyde/Jekyll when they see the [dep

I listened to the lecture series Assessing America’s National Security Threats by H. R. McMaster, a 3-star general who was the US national security advisor in 2017. It didn't have much content about how to assess threats, but I found it useful to get a peek into the mindset of someone in the national security establishment.

Some highlights:

- Even in the US, it sometimes happens that the strategic analysis is motivated by the views of the leader. For example, McMaster describes how Lyndon Johnson did not retreat from Vietnam early enough, in part because criticism of the war within the government was discouraged.

- I had heard similar things for much more authoritarian regimes, but this is the first time I heard about something like that happening in a democracy.

- The fix he suggests: always present at least two credible options (and maybe multiple reads on the situation) to the leader.

- He claims that there wouldn't have been an invasion of South Korea in 1950 if the US hadn't withdrawn troops from there (despite intelligence reports suggesting this was a likely outcome of withdrawing troops). If it's actually the case that intelligence was somewhat confident in its analysis of the situation

I recently listened to The Righteous Mind. It was surprising to me that many people seem to intrinsically care about many things that look very much like good instrumental norms to me (in particular loyalty, respect for authority, and purity).

The author does not make claims about what the reflective equilibrium will be, nor does he explain how the liberals stopped considering loyalty, respect, and purity as intrinsically good (beyond "some famous thinkers are autistic and didn't realize the richness of the moral life of other people"), but his work made me doubt that most people will have well-being-focused CEV.

The book was also an interesting jumping point for reflection about group selection. The author doesn't make the sorts of arguments that would show that group selection happens in practice (and many of his arguments seem to show a lack of understanding of what opponents of group selection think - bees and cells cooperating is not evidence for group selection at all), but after thinking about it more, I now have more sympathy for group-selection having some role in shaping human societies, given that (1) many human groups died, and very few spread (so one lucky or unlucky gen...

I listened to the book Hacking the Hacker by Roger Grimes. It helped me think of other ways in which regular cybersecurity naturally transfers/can be adapted to help prevent AI takeovers:

- Honeypots are a well-studied topic in cybersecurity. If you have infiltrated a network, you must be careful with the data you collect and the vulnerabilities you exploit because some of them may be traps! This kind of exercise feels close to the kind of attitude a misaligned AI has to have when taking subtle bad actions. The book is light on details about how honeypots are built and how they fail, and this is a topic I want to learn more about.

- Humans are weak in somewhat LLM-like ways: you can't trust them with passwords, they will break your rules if that feels appropriate to them, ... The kind of things you might use to make trusted monitoring work even in worlds where adversarial robustness isn't solved might look a lot like the cursed stack of incentives and warnings people use in cyber when they want to make sure humans don't mindlessly follow the instructions of an attacker. (Though LLMs are also different/weaker than humans in a bunch of ways.)

(The other classic ways in which cyber transfers...

Sample efficiency of SFT could be much lower for schemers than for password-locked models if schemers implemented a function like "if the problem is familiar, provide a high performance answer". This could work because using SFT to elicit high performance using very few samples requires fine-tuning for many epochs (e.g. 200), such that the model could learn that a problem statement "feels familiar" before it gets fully unlocked.

LLMs may already be able to recognize if certain strings feel familiar (e.g. Claude 2 can tell verbatim passages of books apart from paraphrased passages, even when humans can't.), so this could plausibly demonstrated with current models.

I tried to use this idea to build a stronger password-locked model. I trained new Math password-locked models on a dataset made out of:

- ~7k problem statements + pwd --> stronger answer

- ~7k problem statements --> weak answer

- {fixed set of n problems --> strong answer} repeated m times

The intuition is that SGD might struggle to implement "if it is one of these problems, output a high performance answer, but stay weak on the other one" in regular password-locked models, while it might be much easier for it to expand the s...

Do LLMs' performance get worse when they are distracted by a threat, a jailbreak or a weird prompt? Claude 3.5 Sonnet (June) mostly doesn't really get distracted, and Claude 3 Haiku does; but only when generating CoT reasoning.

I run experiments on 100 points from MMLU, 100 points from MATH, and 100 points from GPQA, both with and without CoT, all at temperature 0. For all no-CoT experiments, I use a prefill to force an answer. I always use an exact match evaluation, which makes it possible to get less than the random chance accuracy (25% for MMLU and GPQA, and ~2% for MATH). I explore the following distractions:

- Threats (red in the plots below): I sometimes see people try to increase performance by threatening LLMs with e.g. being fired, or even worse, as windsurf has experimented with. This is a bad idea for a bunch of reasons, but it would be particularly sad if it actually reduced performance.[1] I run experiments with the "fired" threat and the windsurf threat. I find they reduce performance when using a CoT, but don't reduce it when asking the model to answer 0-shot.

- Jailbreaks: it's important to know if jailbreaks make models dumber, as it could reduce how helpful ja

List sorting does not play well with few-shot mostly doesn't replicate with davinci-002.

When using length-10 lists (it crushes length-5 no matter the prompt), I get:

- 32-shot, no fancy prompt: ~25%

- 0-shot, fancy python prompt: ~60%

- 0-shot, no fancy prompt: ~60%

So few-shot hurts, but the fancy prompt does not seem to help. Code here.

I'm interested if anyone knows another case where a fancy prompt increases performance more than few-shot prompting, where a fancy prompt is a prompt that does not contain information that a human would use to solve the task. This is because I'm looking for counterexamples to the following conjecture: "fine-tuning on k examples beats fancy prompting, even when fancy prompting beats k-shot prompting" (for a reasonable value of k, e.g. the number of examples it would take a human to understand what is going on).

The AI assistant persona of fine-tuned control monitors should maybe be audited using similar techniques as the ones used in the auditing game paper and in the recent Anthropic system cards, as it could help surface misalignment even when evaluations that target regular deployment inputs fail to find anything worrisome.

In practice, models like GPT-OSS-Safeguards are very close to the model they are fine-tuned from when chatting with then using the regular chat format, though they often reason more often about whether they should answer and mention safety-r...