We founded Anthropic because we believe the impact of AI might be comparable to that of the industrial and scientific revolutions, but we aren’t confident it will go well. And we also believe this level of impact could start to arrive soon – perhaps in the coming decade.

This view may sound implausible or grandiose, and there are good reasons to be skeptical of it. For one thing, almost everyone who has said “the thing we’re working on might be one of the biggest developments in history” has been wrong, often laughably so. Nevertheless, we believe there is enough evidence to seriously prepare for a world where rapid AI progress leads to transformative AI systems.

At Anthropic our motto has been “show, don’t tell”, and we’ve focused on releasing a steady stream of safety-oriented research that we believe has broad value for the AI community. We’re writing this now because as more people have become aware of AI progress, it feels timely to express our own views on this topic and to explain our strategy and goals. In short, we believe that AI safety research is urgently important and should be supported by a wide range of public and private actors.

So in this post we will summarize why we believe all this: why we anticipate very rapid AI progress and very large impacts from AI, and how that led us to be concerned about AI safety. We’ll then briefly summarize our own approach to AI safety research and some of the reasoning behind it. We hope by writing this we can contribute to broader discussions about AI safety and AI progress.

As a high level summary of the main points in this post:

- AI will have a very large impact, possibly in the coming decade

Rapid and continuing AI progress is a predictable consequence of the exponential increase in computation used to train AI systems, because research on “scaling laws” demonstrates that more computation leads to general improvements in capabilities. Simple extrapolations suggest AI systems will become far more capable in the next decade, possibly equaling or exceeding human level performance at most intellectual tasks. AI progress might slow or halt, but the evidence suggests it will probably continue.- We do not know how to train systems to robustly behave well

So far, no one knows how to train very powerful AI systems to be robustly helpful, honest, and harmless. Furthermore, rapid AI progress will be disruptive to society and may trigger competitive races that could lead corporations or nations to deploy untrustworthy AI systems. The results of this could be catastrophic, either because AI systems strategically pursue dangerous goals, or because these systems make more innocent mistakes in high-stakes situations.- We are most optimistic about a multi-faceted, empirically-driven approach to AI safety

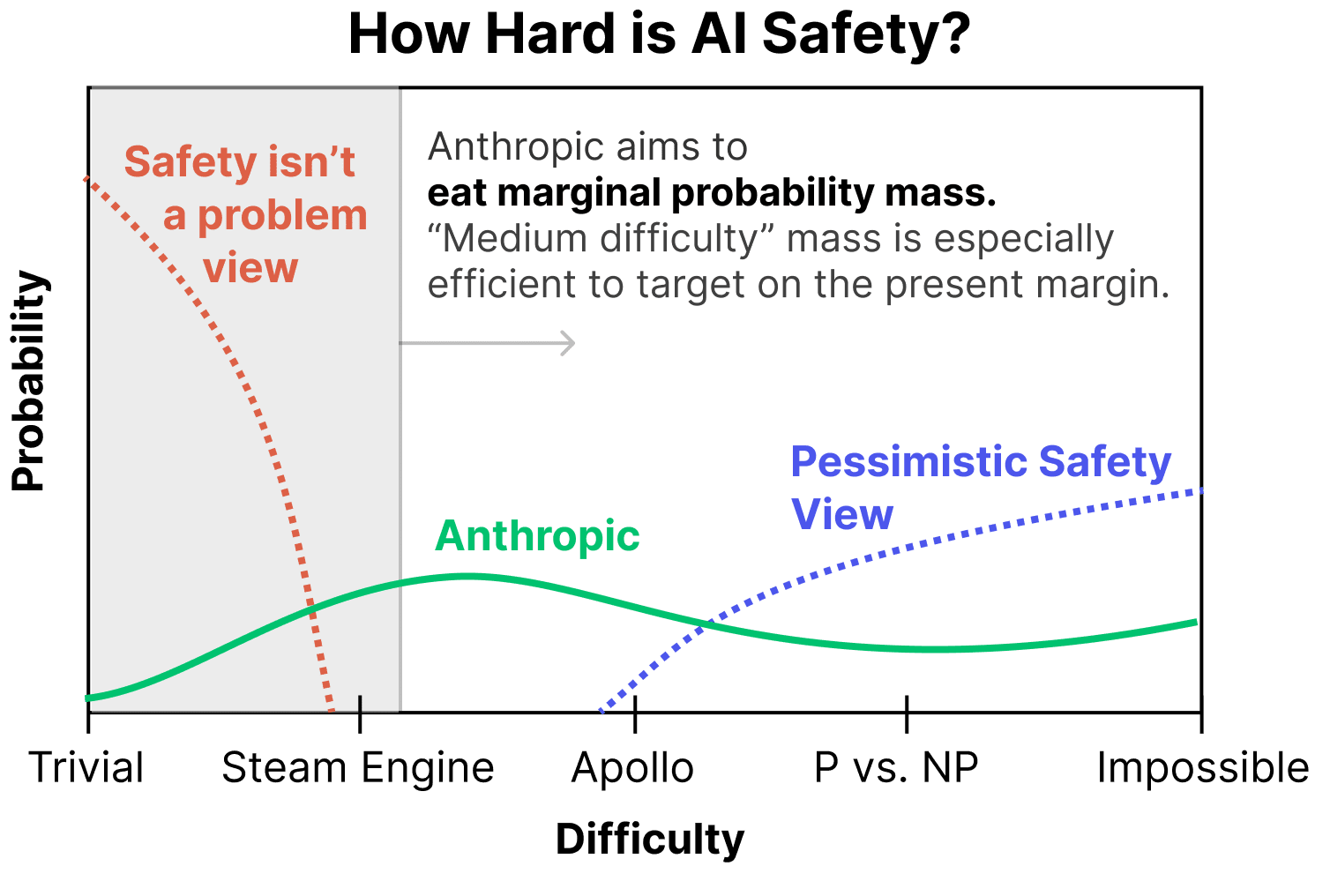

We’re pursuing a variety of research directions with the goal of building reliably safe systems, and are currently most excited about scaling supervision, mechanistic interpretability, process-oriented learning, and understanding and evaluating how AI systems learn and generalize. A key goal of ours is to differentially accelerate this safety work, and to develop a profile of safety research that attempts to cover a wide range of scenarios, from those in which safety challenges turn out to be easy to address to those in which creating safe systems is extremely difficult.

The full post goes into considerably more detail, and I'm really excited that we're sharing more of our thinking publicly.

I wouldn't want to give an "official organizational probability distribution", but I think collectively we average out to something closer to "a uniform prior over possibilities" without that much evidence thus far updating us from there. Basically, there are plausible stories and intuitions pointing in lots of directions, and no real empirical evidence which bears on it thus far.

(Obviously, within the company, there's a wide range of views. Some people are very pessimistic. Others are optimistic. We debate this quite a bit internally, and I think that's really positive! But I think there's a broad consensus to take the entire range seriously, including the very pessimistic ones.)

This is pretty distinct from how I think many people here see things – ie. I get the sense that many people assign most of their probability mass to what we call pessimistic scenarios – but I also don't want to give the impression that this means we're taking the pessimistic scenario lightly. If you believe there's a ~33% chance of the pessimistic scenario, that's absolutely terrifying. No potentially catastrophic system should be created without very compelling evidence updating us against this! And of course, the range of scenarios in the intermediate range are also very scary.

At a very high-level, I think our first goal for most pessimistic scenarios is just to be able to recognize that we're in one! That's very difficult in itself – in some sense, the thing that makes the most pessimistic scenarios pessimistic is that they're so difficult to recognize. So we're working on that.

But before diving into our work on pessimistic scenarios, it's worth noting that – while a non-trivial portion of our research is directed towards pessimistic scenarios – our research is in some ways more invested in optimistic scenarios at the present moment. There are a few reasons for this:

(To be clear, we aren't saying that everyone should work on medium difficulty scenarios – an important part of our work is also thinking about pessimistic scenarios – but this perspective is one reason we find working on medium difficulty worlds very compelling.)

We also have a lot of work that I might describe as trying to move from optimistic scenarios towards more intermediate scenarios. This includes our process-oriented learning and scalable supervision agendas.

But what are we doing now to address pessimistic scenarios? (Again, remember that our primary goal for pessimistic scenarios is just to recognize that we're in one and generate compelling evidence that can persuade the world.)

To be clear, we think pessimistic scenarios are, well, pessimistic and hard! These are our best preliminary attempts at agendas for addressing them, and we expect to change and expand as we learn more. Additionally, as we make progress on the more optimistic scenarios, I expect the number of projects we have targeted on pessimistic scenarios to increase.