We founded Anthropic because we believe the impact of AI might be comparable to that of the industrial and scientific revolutions, but we aren’t confident it will go well. And we also believe this level of impact could start to arrive soon – perhaps in the coming decade.

This view may sound implausible or grandiose, and there are good reasons to be skeptical of it. For one thing, almost everyone who has said “the thing we’re working on might be one of the biggest developments in history” has been wrong, often laughably so. Nevertheless, we believe there is enough evidence to seriously prepare for a world where rapid AI progress leads to transformative AI systems.

At Anthropic our motto has been “show, don’t tell”, and we’ve focused on releasing a steady stream of safety-oriented research that we believe has broad value for the AI community. We’re writing this now because as more people have become aware of AI progress, it feels timely to express our own views on this topic and to explain our strategy and goals. In short, we believe that AI safety research is urgently important and should be supported by a wide range of public and private actors.

So in this post we will summarize why we believe all this: why we anticipate very rapid AI progress and very large impacts from AI, and how that led us to be concerned about AI safety. We’ll then briefly summarize our own approach to AI safety research and some of the reasoning behind it. We hope by writing this we can contribute to broader discussions about AI safety and AI progress.

As a high level summary of the main points in this post:

- AI will have a very large impact, possibly in the coming decade

Rapid and continuing AI progress is a predictable consequence of the exponential increase in computation used to train AI systems, because research on “scaling laws” demonstrates that more computation leads to general improvements in capabilities. Simple extrapolations suggest AI systems will become far more capable in the next decade, possibly equaling or exceeding human level performance at most intellectual tasks. AI progress might slow or halt, but the evidence suggests it will probably continue.- We do not know how to train systems to robustly behave well

So far, no one knows how to train very powerful AI systems to be robustly helpful, honest, and harmless. Furthermore, rapid AI progress will be disruptive to society and may trigger competitive races that could lead corporations or nations to deploy untrustworthy AI systems. The results of this could be catastrophic, either because AI systems strategically pursue dangerous goals, or because these systems make more innocent mistakes in high-stakes situations.- We are most optimistic about a multi-faceted, empirically-driven approach to AI safety

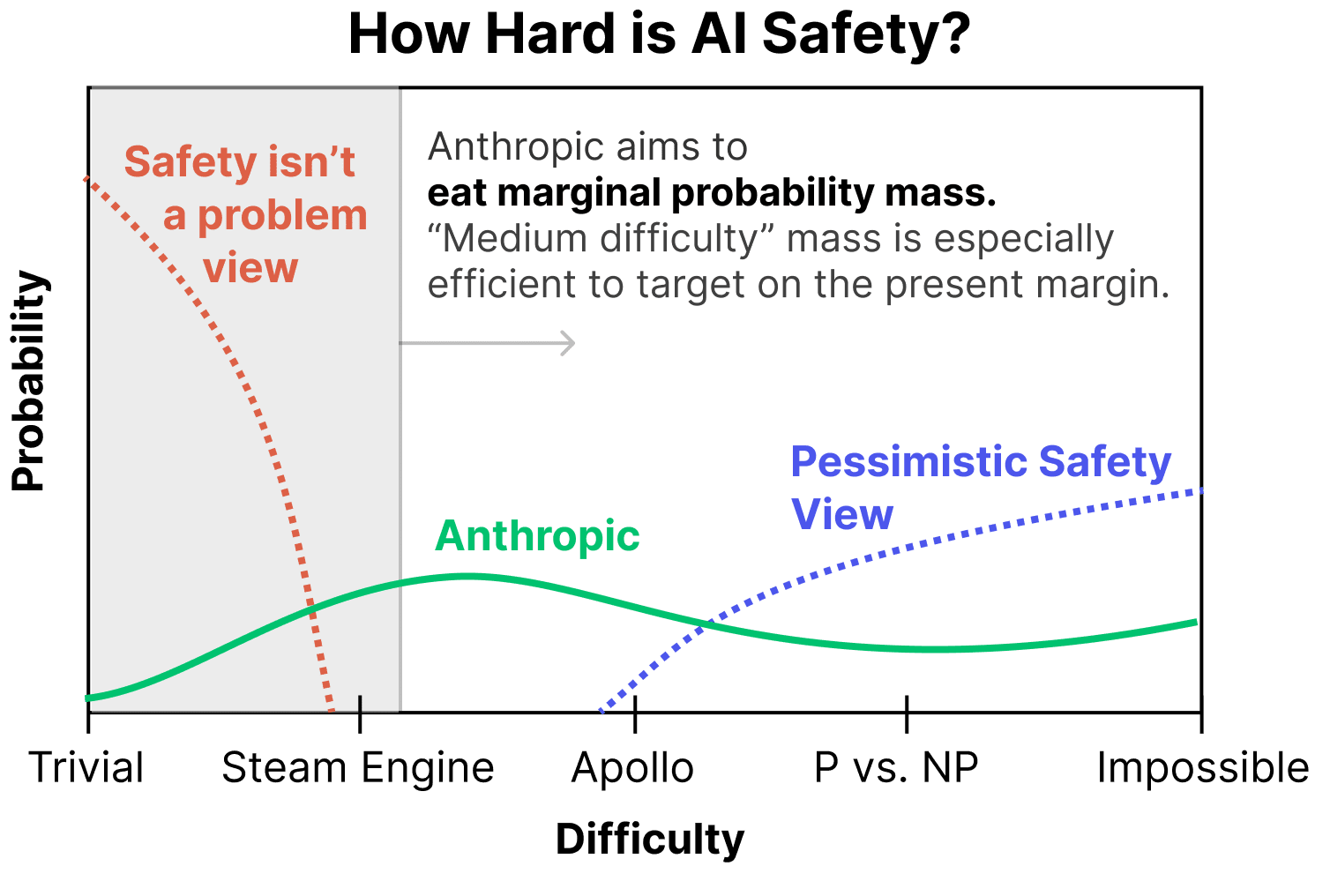

We’re pursuing a variety of research directions with the goal of building reliably safe systems, and are currently most excited about scaling supervision, mechanistic interpretability, process-oriented learning, and understanding and evaluating how AI systems learn and generalize. A key goal of ours is to differentially accelerate this safety work, and to develop a profile of safety research that attempts to cover a wide range of scenarios, from those in which safety challenges turn out to be easy to address to those in which creating safe systems is extremely difficult.

The full post goes into considerably more detail, and I'm really excited that we're sharing more of our thinking publicly.

The weird thing about a portfolio approach is that the things it makes sense to work on in “optimistic scenarios” often trade off against those you’d want to work on in more “pessimistic scenarios,” and I don't feel like this is really addressed.

Like, if we’re living in an optimistic world where it’s pretty chill to scale up quickly, and things like deception are either pretty obvious or not all that consequential, and alignment is close to default, then sure, pushing frontier models is fine. But if we’re in a world where the problem is nearly impossible, alignment is nowhere close to default, and/or things like deception happen in an abrupt way, then the actions Anthropic is taking (e.g., rapidly scaling models) are really risky.

This is part of what seems weird to me about Anthropic’s safety plan. It seems like the major bet the company is making is that getting empirical feedback from frontier systems is going to help solve alignment. Much of that justification (afaict from the Core Views post) is because Anthropic expects to be surprised by what emerges in larger models. For instance, as this Anthropic paper mentions: models can’t do 3 digit addition basically at all (close to 0% test accuracy) until all of the sudden, as you scale the model slightly, they can (0% to 80% accuracy abruptly). I presume the safety model here is something like: if you can’t make much progress on problems without empirical feedback, and if you can’t get the empirical feedback unless the capability is present to work with, and if capabilities (or their precursors) only emerge at certain scales, then scaling is a bottleneck to alignment progress.

I’m not convinced by those claims, but I think that even if I were, I would have a very different sense of what to do here. Like, it seems to me that our current state of knowledge about how and why specific capabilities emerge (and when they do) is pretty close to “we have no idea.” That means we are pretty close to having no idea about when and how and why dangerous capabilities might emerge, nor whether they’ll do so continuously or abruptly.

My impression is that Dario agrees with this:

If I put on the “we need empirical feedback from neural nets to make progress on alignment” hat, along with my “prudence” hat, I’m thinking things more like, “okay let’s stop scaling now, and just work really hard on figuring out how exactly capabilities emerged between e.g., GPT-3 and GPT-4. Like, what exactly can we predict about GPT-4 based on GPT-3? Can we break down surprising and abrupt less-scary capabilities into understandable parts, and generalize from that to more-scary capabilities?” Basically, I’m hoping for a bunch more proof of concept that Anthropic is capable of understanding and controlling current systems, before they scale blindly. If they can’t do it now, why should I expect they’ll be able to do it then?

My guess is that a bunch of these concerns are getting swept under the “optimistic scenario” rug, i.e., “sure, maybe we’d do that if we only expected a pessimistic scenario, but we don’t! And in the optimistic scenario, scaling is pretty much fine, and we can grab more probability mass there so we’re choosing to scale and do the safety we can conditioned on that.” I find this dynamic frustrating. The charitable read on having a uniform prior over outcomes is that you’re taking all viewpoints seriously. The uncharitable read is that it gives you enough free parameters and wiggle room to come to the conclusion that “actually scaling is good” no matter what argument someone levies, because you can always make recourse to a different expected world.

Like, even in pessimistic scenarios (where alignment is nearly impossible), Anthropic still concludes they should be scaling in order to “sound the alarm bell,” despite not saying all that much about how that would work, or if it would work, or making any binding commitments, or saying what precautions they’re taking to make sure they would end up in the “sound the alarm bell” world instead of the “now we’re fucked” world, which are pretty close together. Instead they are taking the action “rapidly scaling systems even though we publicly admit to being in a world where it’s unclear how or when or why different capabilities emerge, nor whether they’ll do so abruptly, and we haven’t figured out how to control these systems in the most basic ways.” I don’t understand how Anthropic thinks this is safe.

The safety model for pushing frontier models as much as Anthropic is doing doesn’t make sense to me. If you’re expecting to be surprised by newer models, that’s bad. We should be aiming to not be surprised, so that we have any hope of managing something that might be much smarter and more powerful than us. The other reasons this blog post lists for working on frontier models seem similarly strange to me, although I’ll leave it here for now. From where I’m at, it doesn’t seem like safety concerns really justify pushing frontier models, and I’d like to hear Anthropic defend this claim more, given that they cite it as one of the main reasons they exist:

(I’d honestly like to be convinced this does make sense, if I’m missing something here).