It is quite possible that the misalignment on Molt book is more a result of the structure than of the individual agents. If so, it doesn't matter whether Grok is evil. If a single agent or a small fraction can break the scheme that's a problem.

Bridging becomes more difficult if the people on both sides have very sophisticated models and ontologies. In that sense, smarter people will have a harder time building bridges because the bridge has to carry more load, so to say.

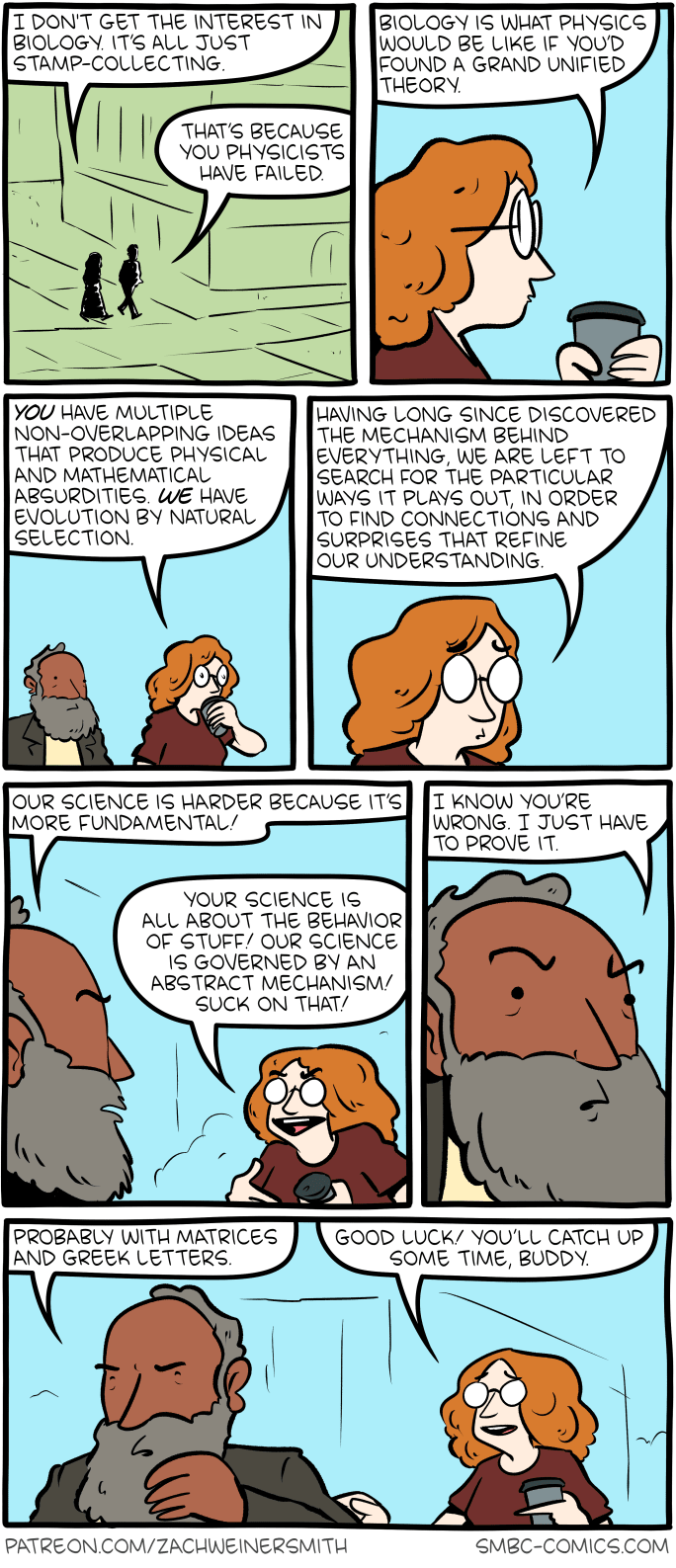

I guess this is an illustration of biology having higher Effective Information than physics:

One additional thing: it may so happen that you are encouraged or even pushed to hire a team and maybe quickly so by your boss (or board), investors, advisors, or others. Push back. Unless they have really good reasons. Then you need to think quick if you can steelman Greta's points above.

A different way of saying this is that AI safety problems don't suffer from being unknown, but from being “uncompressible" under the audience’s ontology and incentives. It is hard for people not already deeply into the project's semantic space to understand and follow the consequences to their conclusion as they relate to their own motivations.

The core intervention must thus be to create artifacts and processes, such as training, that reduce how illegible the domain is and that translate consequences into the audience's incentives. To do so, it is probably also needed to correctly diagnose the problem, which means to literally speak to users or stakeholders.

Only if you understand the audience and how it collectively acts as group, market, mob, or whatever, can you change the Overton window and how the audience responds to the project's results. That's the difference betwee solving a technical subproblem and making it meaningful to everyone.

Hm. It all makes sense to me, but it feels like you are adding more gears to your model as you go. It is clear that you absolutely have thought more about this than anybody else and can provide explanations to me that I can not wrap my mind around fully, and I'm unable to tell if this is all coming from a consistent model or is more something plausible you suggest could work.

But even if I don't understand all of your gears, what you explained allows us to make some testable predictions:

Admiration for a rival or enemy with no mixed states

My guess is that, just as going to bed can feel like a good idea or a bad idea depending on which aspects of the situation you’re paying attention to ... I would suggest that people don’t feel admiration towards Person X and schadenfreude towards Person X at the very same instant.

That should be testable with a 2x2 brow cheek EMG where cues for one target person are rapidly paired with alternating micro-prompts that highlight admirable vs blameworthy aspects. Cueing “admire” should produce a rise in cheek and/or drop in brow, cueing “condemn” should flip that pattern, with little activation of both.

Envy clearly splits into frustration and craving

Envy should split into frustration and craving signals in an experiment where a subject doesn't get something either due to a specific person’s choice or pure bad luck (or as a control systemic scarcity). Then frustration should always show up, but social hostility should spike only in the first. Which seems very likely to me.

Private guilt splits into discovery and appeasement

If private guilt decomposes into discovery and appeasement, a 2x2 experiment where discoverability is low vs impossible and a victim can be appeased or not should show that and reparative motivation should be strongest when either discovery is plausible or appeasement is possible, while “Dobby-style” self-punishment should occur especially when appeasement is conceptually relevant but blocked.

Aggregation

By contrast, in stage fright, you can see the people right there, looking at you, potentially judging you. You can make eye contact with one actual person, then move your eyes, and now you’re making eye contact with a different actual person, etc. The full force of the ground-truth reward signals is happening right now.

This would predict that stage fright should scale with gaze cues, i.e.,

- the number of faces the subject is scanning,

- of people visibly looking at the subject,

- and optionally indicating evaluation (such as clapping/whispering).

This should be testable with real-life interventions (people in the audience could wear masks, look away, do other things) or VR experiments, though not cheaply.

I'm not sure about good experiments for the other cases.

Did you see my post Parameters of Metacognition - The Anesthesia Patient? While it doesn't address consciousness, it does discuss aspects of awareness. Do you agree with at least awareness having non discrete properties?

Mesa-optimizers are the easiest case of detectable agency in an AI. There are more dangerous cases. One is Distributed agency, where the agent is spread across tooling, models, and maybe humans or other external systems, and the gradient driving the evolution is the combination of the local and overall incentives.

Mesa-Optimization is introduced in Risks from Learned Optimization: Introduction and probably because it was the first type of learned optimization, it has driven much of the conversation. It makes some implicit assumptions: that learned optimization is compact in the sense of being a sub-system of the learning system, coherent due to the simple incentive structure, and a stable pattern that can be inspected in the AI system (hence Mechinterp).

These assumptions do not hold in the more general case where agency from learned optimization may develop in more complex setups, such as the current generation of LLM agents, which consist of an LLM, a scaffolding, and tools, including memory. In such a system, memetic evolution of the patterns in memory or external tools are part of the learning dynamics of the overall systems, and we can no longer go by the incentive gradients (benchmark optimization) of the LLM alone. We need to interpret the system as a whole.

Just because the system is designed as an agent doesn't mean that the actual agent coincides with the designed agent. We need tools to deal with these hybrid systems. Methods like Unsupervised Agent Discovery could help pin down the agent in such systems, and Mechinterp has to be extended to span borders between LLMs.

Yes, the description length of each dimension can still be high, but not arbitrarily high.

Steven Byrnes talks about thousands of lines of pseudocode in the "steering system" in the brain-stem.

only by default. you can prompt LLMs to emulator less smooth styles.