AI Doomerism in 1879

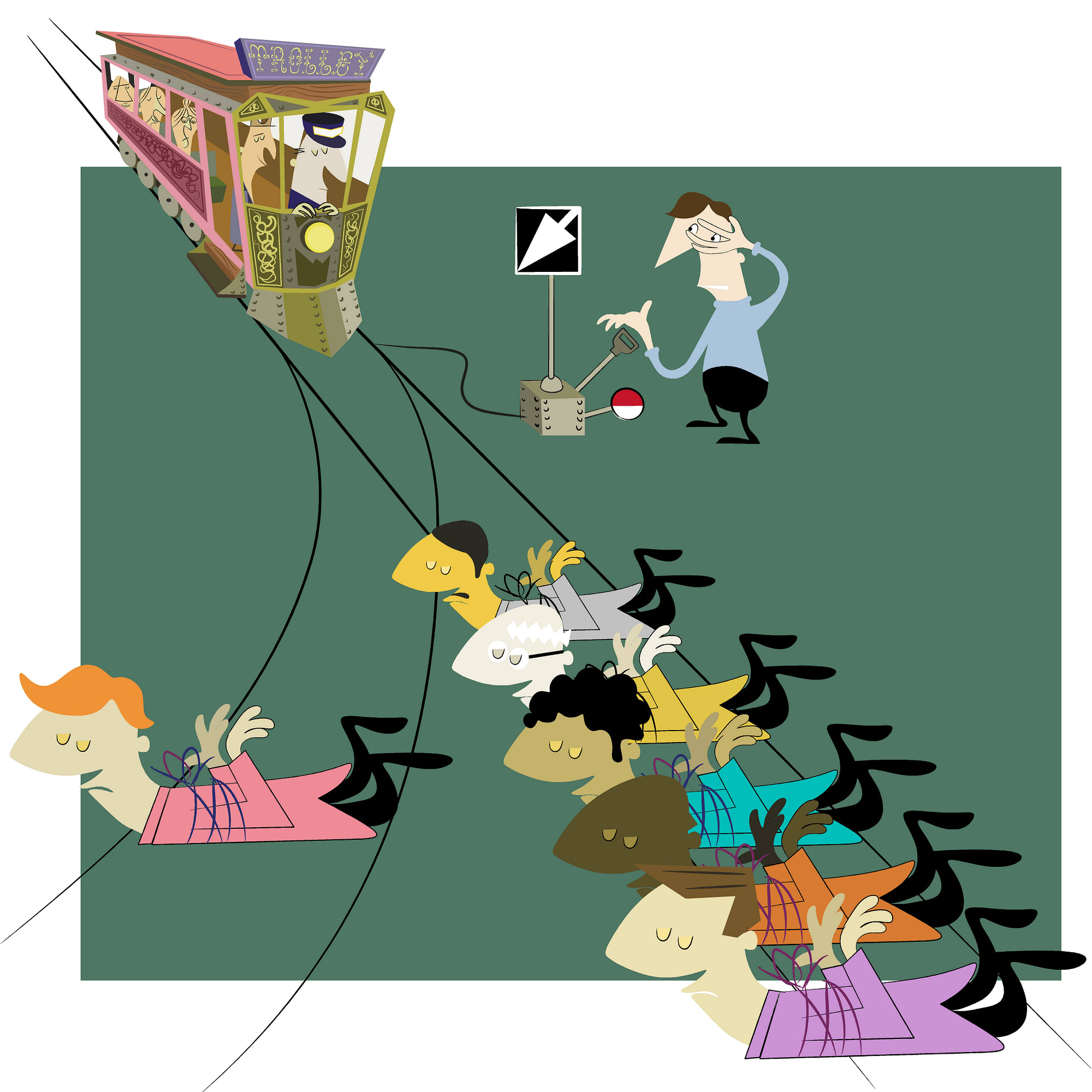

I’m reading George Eliot’s Impressions of Theophrastus Such (1879)—so far a snoozer compared to her novels. But chapter 17 surprised me for how well it anticipated modern AI doomerism. In summary, Theophrastus is in conversation with Trost, who is an optimist about the future of automation and how it will free us from drudgery and permit us to further extend the reach of the most exalted human capabilities. Theophrastus is more concerned that automation is likely to overtake, obsolete, and atrophy human ability. Among Theophrastus’s concerns: * People will find that they no longer can do labor that is valuable enough to compete with the machines. * This will eventually include intellectual labor, as we develop for example “a machine for drawing the right conclusion, which will doubtless by-and-by be improved into an automaton for finding true premises.” * Whereupon humanity will finally be transcended and superseded by its own creation, which can do anything we can do but faster, more precisely, and with less fuss. * Though Trost insists that such machines will require human skill to construct and operate and interpret, Theophrastus thinks there is no reason to believe that they may not eventually come to build, repair, and feed themselves, at which point this “must drive men altogether out of the field.” * In such a scheme of things, consciousness is an unnecessary and obsolete inefficiency. “[T]his planet may be filled with beings who will be blind and deaf as the inmost rock, yet will execute changes as delicate and complicated as those of human language, and all the intricate web of what we call its effects, without sensitive impression, without sensitive impulse: there may be, let us say, mute orations, mute discussions, and no consciousness there even to enjoy the silence.” I attach the chapter below: Impressions of Theophrastus Such Chapter XVII: Shadows of the Coming Race My friend Trost, who is no optim

good Christians everywhere

good Christians everywhere

FWIW, I asked Claude for its opinion today. It thought that new communication media/dynamics (A7, B14, B15 along with B8 & B9) were likely to blame, and that survivorship bias (A12) probably also plays a role.

Claude also suggested I add "The collapse of shared epistemic authorities" as another hypothesis, similar to but distinct from B15: "It's not just that gatekeepers died; it's that there's no longer any institution or process that a broad majority accepts as capable of settling factual questions. When people disagree about facts, there's no court of appeal. This makes all disagreement look like stupidity from the other side's perspective, because there's no shared standard by which to adjudicate it."