All of Johannes Treutlein's Comments + Replies

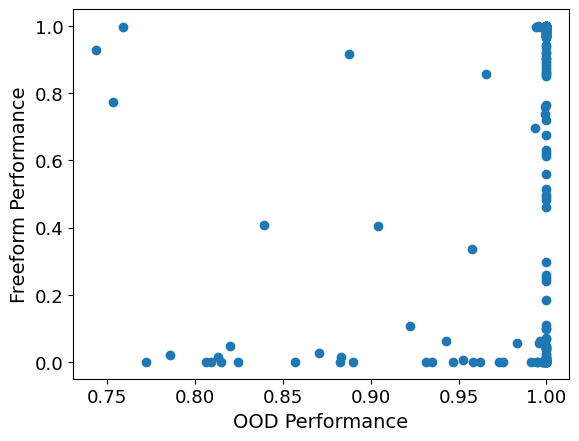

I played around with this a little bit now. First, I correlated OOD performance vs. Freeform definition performance, for each model and function. I got a correlation coefficient of ca. 0.16. You can see a scatter plot below. Every dot corresponds to a tuple of a model and a function. Note that transforming the points into logits or similar didn't really help.

Next, I took one of the finetunes and functions where OOD performance wasn't perfect. I choose 1.75 x and my first functions finetune (OOD performance at 82%). Below, I plot the function values that th...

My guess is that for any given finetune and function, OOD regression performance correlates with performance on providing definitions, but that the model doesn't perform better on its own provided definitions than on the ground truth definitions. From looking at plots of function values, the way they are wrong OOD often looked more like noise or calculation errors to me rather than eg getting the coefficient wrong. I'm not sure, though. I might run an evaluation on this soon and will report back here.

How much time do you think there is between "ability to automate" and "actually this has been automated"? Are your numbers for actual automation, or just ability? I personally would agree to your numbers if they are about ability to automate, but I think it will take much longer to actually automate, due to people's inertia and normal regulatory hurdles (though I find it confusing to think about, because we might have vastly superhuman AI and potentially loss of control before everything is actually automated.)

I found this clarifying for my own thinking! Just a small additional point, in Hidden Incentives for Auto-Induced Distributional Shift, there is also the example of a Q learner that learns to sometimes take a non-myopic action (I believe cooperating with its past self in a prisoner's dilemma), without any meta learning.

Thank you! :)

Yes, one could e.g. have a clear disclaimer above the chat window saying that this is a simulation and not the real Bill Gates. I still think this is a bit tricky. E.g., Bill Gates could be really persuasive and insist that the disclaimer is wrong. Some users might then end up believing Bill Gates rather than the disclaimer. Moreover, even if the user believes the disclaimer on a conscious level, impersonating someone might still have a subconscious effect. E.g., imagine an AI friend or companion who repeatedly reminds you that they are just an AI, versus ...

My takeaway from looking at the paper is that the main work is being done by the assumption that you can split up the joint distribution implied by the model as a mixture distribution

such that the model does Bayesian inference in this mixture model to compute the next sentence given a prompt, i.e., we have . Together with the assumption that is always bad (the sup condition you talk about), this makes the whole approach with giving more and more evidence for by stringing together bad se...

Fixed links to all the posts in the sequence:

- Acausal trade: Introduction

- Acausal trade: double decrease

- Acausal trade: universal utility, or selling non-existence insurance too late

- Acausal trade: full decision algorithms

- Acausal trade: trade barriers

- Acausal trade: different utilities, different trades

- Acausal trade: being unusual

- Acausal trade: conclusion: theory vs practice

Fixed links to all the posts in the sequence:

- Acausal trade: Introduction

- Acausal trade: double decrease

- Acausal trade: universal utility, or selling non-existence insurance too late

- Acausal trade: full decision algorithms

- Acausal trade: trade barriers

- Acausal trade: different utilities, different trades

- Acausal trade: being unusual

- Acausal trade: conclusion: theory vs practice

Fixed links to all the posts in the sequence:

- Acausal trade: Introduction

- Acausal trade: double decrease

- Acausal trade: universal utility, or selling non-existence insurance too late

- Acausal trade: full decision algorithms

- Acausal trade: trade barriers

- Acausal trade: different utilities, different trades

- Acausal trade: being unusual

- Acausal trade: conclusion: theory vs practice

Fixed links to all the posts in the sequence:

- Acausal trade: Introduction

- Acausal trade: double decrease

- Acausal trade: universal utility, or selling non-existence insurance too late

- Acausal trade: full decision algorithms

- Acausal trade: trade barriers

- Acausal trade: different utilities, different trades

- Acausal trade: being unusual

- Acausal trade: conclusion: theory vs practice

Fixed links to all the posts in the sequence:

- Acausal trade: Introduction

- Acausal trade: double decrease

- Acausal trade: universal utility, or selling non-existence insurance too late

- Acausal trade: full decision algorithms

- Acausal trade: trade barriers

- Acausal trade: different utilities, different trades

- Acausal trade: being unusual

- Acausal trade: conclusion: theory vs practice

Fixed links to all the posts in the sequence:

- Acausal trade: Introduction

- Acausal trade: double decrease

- Acausal trade: universal utility, or selling non-existence insurance too late

- Acausal trade: full decision algorithms

- Acausal trade: trade barriers

- Acausal trade: different utilities, different trades

- Acausal trade: being unusual

- Acausal trade: conclusion: theory vs practice

Fixed links to all the posts in the sequence:

- Acausal trade: Introduction

- Acausal trade: double decrease

- Acausal trade: universal utility, or selling non-existence insurance too late

- Acausal trade: full decision algorithms

- Acausal trade: trade barriers

- Acausal trade: different utilities, different trades

- Acausal trade: being unusual

- Acausal trade: conclusion: theory vs practice

Since the links above are broken, here are links to all the other posts in the sequence:

- This post

- Acausal trade: double decrease

- Acausal trade: universal utility, or selling non-existence insurance too late

- Acausal trade: full decision algorithms

- Acausal trade: trade barriers

- Acausal trade: different utilities, different trades

- Acausal trade: being unusual

- Acausal trade: conclusion: theory vs practice

Some further thoughts on training ML models, based on discussions with Caspar Oesterheld:

- I don't see a principled reason why one couldn't use one and the same model for both agents. I.e., do standard self-play training with weight sharing for this zero-sum game. Since both players have exactly the same loss function, we don't need to allow them to specialize by feeding in a player id or something like that (there exists a symmetric Nash equilibrium).

- There is one problem with optimizing the objective in the zero-sum game via gradient descent (assuming we co

Regarding your last point 3., why does this make you more pessimistic rather than just very uncertain about everything?

Why would alignment with the outer reward function be the simplest possible terminal goal? Specifying the outer reward function in the weights would presumably be more complicated. So one would have to specify a pointer towards it in some way. And it's unclear whether that pointer is simpler than a very simple misaligned goal.

Such a pointer would be simple if the neural network already has a representation of the outer reward function in weights anyway (rather than deriving it at run-time in the activations). But it seems likely that any fixed representati...

I am not sure I understand. Are you saying that GPT thinks the text is genuinely from the future (i.e., the distribution that it is modeling contains text from the future), or that it doesn't think so? The sentence you quote is intended to mean that it does not think the text is genuinely from the future.

Thanks for your comment!

Regarding 1: I don't think it would be good to simulate superintelligences with our predictive models. Rather, we want to simulate humans to elicit safe capabilities. We talk more about competitiveness of the approach in Section III.

Regarding 3: I agree it might have been good to discuss cyborgism specifically. I think cyborgism is to some degree compatible with careful conditioning. One possible issue when interacting with the model arises when the model is trained on / prompted with its own outputs, or data that has been influence...

You are right, thanks for the comment! Fixed it now.

I like the idea behind this experiment, but I find it hard to tell from this write-up what is actually going on. I.e., what is exactly the training setup, what is exactly the model, which parts are hard-coded and which parts are learned? Why is it a weirdo janky thing instead of some other standard model or algorithm? It would be good if this was explained more in the post (it is very effortful to try to piece this together by going through the code). Right now I have a hard time making any inferences from the results.

Update: we recently discovered the performative prediction (Perdomo et al., 2020) literature (HT Alex Pan). This is a machine learning setting where we choose a model parameter (e.g., parameters for a neural network) that minimizes expected loss (e.g., classification error). In performative prediction, the distribution over data points can depend on the choice of model parameter. Our setting is thus a special case in which the parameter of interest is a probability distribution, the loss is a scoring function, and data points are discrete outcomes. Most re...

I think there should be a space both for in-progress research dumps and for more worked out final research reports on the forum. Maybe it would make sense to have separate categories for them or so.

I'm not sure I understand what you mean by a skill-free scoring rule. Can you elaborate what you have in mind?

Thanks for your comment!

Your interpretation sounds right to me. I would add that our result implies that it is impossible to incentivize honest reports in our setting. If you want to incentivize honest reports when is constant, then you have to use a strictly proper scoring rule (this is just the definition of “strictly proper”). But we show for any strictly proper scoring rule that there is a function such that a dishonest prediction is optimal.

Proposition 13 shows that it is possible to “tune” scoring rules to make optimal predictions very close to h...

I think such a natural progression could also lead to something similar to extinction (in addition to permanently curtailing humanity's potential). E.g., maybe we are currently in a regime where optimizing proxies harder still leads to improvements to the true objective, but this could change once we optimize those proxies even more. The natural progression could follow an inverted U-shape.

E.g., take the marketing example. Maybe we will get superhuman persuasion AIs, but also AIs that protect us from persuasive ads and AIs that can provide honest reviews. ...

There is a chance that one can avoid having to solve ontology identification in general if one punts the problem to simulated humans. I.e., it seems one can train the human simulator without solving it, and then use simulated humans to solve the problem. One may have to solve some specific ontology identification problems to make sure one gets an actual human simulator and not e.g. a malign AI simulator. However, this might be easier than solving the problem in full generality.

Minor comment: regarding the RLHF example, one could solve the problem implicitl...

(I think Stockfish would be classified as AI in computer science. I.e., you'd learn about the basic algorithms behind it in a textbook on AI. Maybe you mean that Stockfish was non-ML, or that it had handcrafted heuristics?)

Great post!

I like that you point out that we'd normally do trial and error, but that this might not work with AI. I think you could possibly make clearer where this fails in your story. You do point out how HLMI might become extremely widespread and how it might replace most human work. Right now it seems to me like you argue essentially that the problem is a large-scale accident that comes from a distribution shift. But this doesn't yet say why we couldn't e.g. just continue trial-and-error and correct the AI once we notice that something is going wrong.&...

Overall I agree that solutions to deception look different from solutions to other kinds of distributional shift. (Also, there are probably different solutions to different kinds of large distributional shift as well. E.g., solutions to capability generalization vs solutions to goal generalization.)

I do think one could claim that some general solutions to distributional shift would also solve deceptiveness. E.g., the consensus algorithm works for any kind of distributional shift, but it should presumably also avoid deceptiveness (in the sense that it would...

I like this post and agree that there are different threat models one might categorize broadly under "inner alignment". Before reading this I hadn't reflected on the relationship between them.

Some random thoughts (after an in-person discussion with Erik):

- For distributional shift and deception, there is a question of what is treated as fixed and what is varied when asking whether a certain agent has a certain property. E.g., I could keep the agent constant but put it into a new environment, and ask whether it is still aligned. Or I could keep the environmen

Great post!

Regarding your “Redirecting civilization” approach: I wonder about the competitiveness of this. It seems that we will likely build x-risk-causing AI before we have a good enough model to be able to e.g. simulate the world 1000 years into the future on an alternative timeline? Of course, competitiveness is an issue in general, but the more factored cognition or IDA based approaches seem more realistic to me.

...Alternatively, we can try to be clever and “import” research from the future repeatedly. For instance we can first ask our model to produce r

These issues of preferences over objects of different types (internal states, policies, actions, etc.) and how to translate between them are also discussed in the post Agents Over Cartesian World Models.

Your post seems to be focused more on pointing out a missing piece in the literature rather than asking for a solution to the specific problem (which I believe is a valuable contribution). Regardless, here is roughly how I would understand “what they mean”:

Let be the task space, the output space, the model space, our base objective, and the mesa objective of the model for input . Assume that there exists some map mapping internal objects to outputs by the model,...

Thank you!

It does seem like simulating text generated by using similar models would be hard to avoid when using the model as a research assistant. Presumably any research would get “contaminated” at some point, and models might seize to be helpful without updating them on the newest research.

In theory, if one were to re-train models from scratch on the new research, this might be equivalent to the models updating on the previous models' outputs before reasoning about superrationality, so it would turn things into a version of Newcomb's problem with transpa...

Thanks for your comment! I agree that we probably won't be able to get a textbook from the future just by prompting a language model trained on human-generated texts.

As mentioned in the post, maybe one could train a model to also condition on observations. If the model is very powerful, and it really believes the observations, one could make it work. I do think sometimes it would be beneficial for a model to attain superhuman reasoning skills, even if it is only modeling human-written text. Though of course, this might still not happen in practice.

Overall ...

Would you count issues with malign priors etc. also as issues with myopia? Maybe I'm missing something about what myopia is supposed to mean and be useful for, but these issues seem to have a similar spirit of making an agent do stuff that is motivated by concerns about things happening at different times, in different locations, etc.

E.g., a bad agent could simulate 1000 copies of the LCDT agent and reward it for a particular action favored by the bad agent. Then depending on the anthropic beliefs of the LCDT agent, it might behave so as to maximize this r...

If someone had a strategy that took two years, they would have to over-bid in the first year, taking a loss. But then they have to under-bid on the second year if they're going to make a profit, and--"

"And they get undercut, because someone figures them out."

I think one could imagine scenarios where the first trader can use their influence in the first year to make sure they are not undercut in the second year, analogous to the prediction market example. For instance, the trader could install some kind of encryption in the software that this company use...

I find this particularly curious since naively, one would assume that weight sharing implicitly implements a simplicity prior, so it should make optimization more likely and thus also deceptive behavior? Maybe the argument is that somehow weight sharing leaves less wiggle room for obscuring one's reasoning process, making a potential optimizer more interpretable? But the hidden states and tied weights could still be encoding deceptive reasoning in an uninterpretable way?

I'd also be curious about this!

Which program is that, if I may ask?

Wolfgang Spohn develops the concept of a "dependency equilibrium" based on a similar notion of evidential best response (Spohn 2007, 2010). A joint probability distribution is a dependency equilibrium if all actions of all players that have positive probability are evidential best responses. In case there are actions with zero probability, one evaluates a sequence of joint probability distributions such that and for all actions and . Using your notation of a probability matrix and a utility matrix, the expected utili

...I would like to submit the following entries:

A typology of Newcomblike problems (philosophy paper, co-authored with Caspar Oesterheld).

A wager against Solomonoff induction (blog post).

Three wagers for multiverse-wide superrationality (blog post).

UDT is “updateless” about its utility function (blog post). (I think this post is hard to understand. Nevertheless, if anyone finds it intelligible, I would be interested in their thoughts.)

EDT doesn't pay if it is given the choice to commit to not paying ex-ante (before receiving the letter). So the thought experiment might be an argument against ordinary EDT, but not against updateless EDT. If one takes the possibility of anthropic uncertainty into account, then even ordinary EDT might not pay the blackmailer. See also Abram Demski's post about the Smoking Lesion. Ahmed and Price defend EDT along similar lines in a response to a related thought experiment by Frank Arntzenius.

Thanks for your answer! This "gain" approach seems quite similar to what Wedgwood (2013) has proposed as "Benchmark Theory", which behaves like CDT in cases with, but more like EDT in cases without causally dominant actions. My hunch would be that one might be able to construct a series of thought-experiments in which such a theory violates transitivity of preference, as demonstrated by Ahmed (2012).

I don't understand how you arrive at a gain of 0 for not smoking as a smoke-lover in my example. I would think the gain for not smoking is higher:

...

From my perspective, I don’t think it’s been adequately established that we should prefer updateless CDT to updateless EDT

I agree with this.

It would be nice to have an example which doesn’t arise from an obviously bad agent design, but I don’t have one.

I’d also be interested in finding such a problem.

I am not sure whether your smoking lesion steelman actually makes a decisive case against evidential decision theory. If an agent knows about their utility function on some level, but not on the epistemic level, then this can just as well be made into a

......Imagine that Omega tells you that it threw its coin a million years ago, and would have turned the sky green if it had landed the other way. Back in 2010, I wrote a post arguing that in this sort of situation, since you've always seen the sky being blue, and every other human being has also always seen the sky being blue, everyone has always had enough information to conclude that there's no benefit from paying up in this particular counterfactual mugging, and so there hasn't ever been any incentive to self-modify into an agent that would pay up ... and s

I think there is a difference between finetuning and prompting in that in the prompting case, the LLM is aware that it's taking part in a role playing scenario. With finetuning on synthetic documents, it is possible to make the LLM more deeply believe something. Maybe one could make the finetuning more sample efficient by instead distilling a prompted model. Another option could be using steering vectors, though I'm not sure that would work better than prompting.