Thanks to Jesse Richardson for discussion.

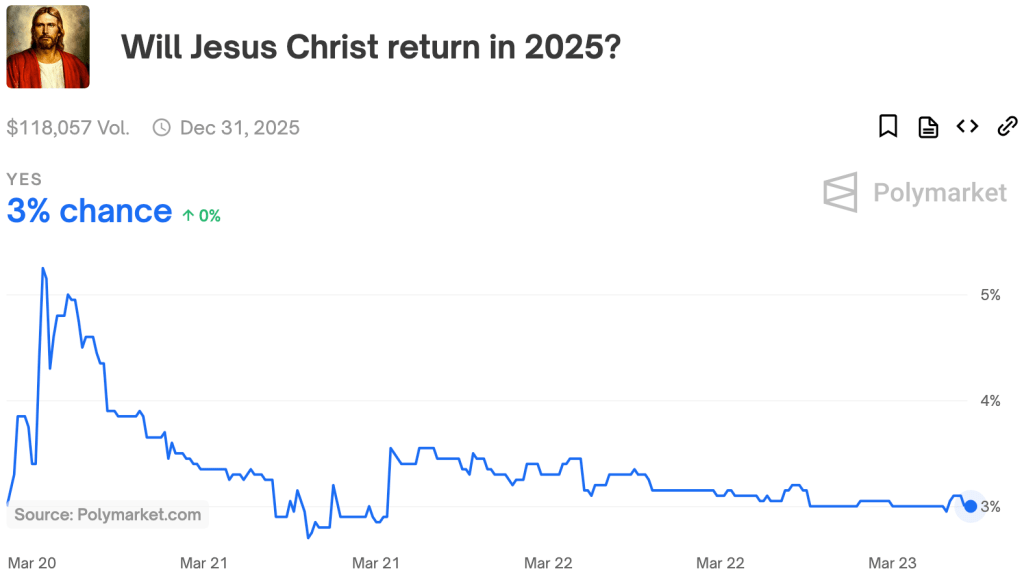

Polymarket asks: will Jesus Christ return in 2025?

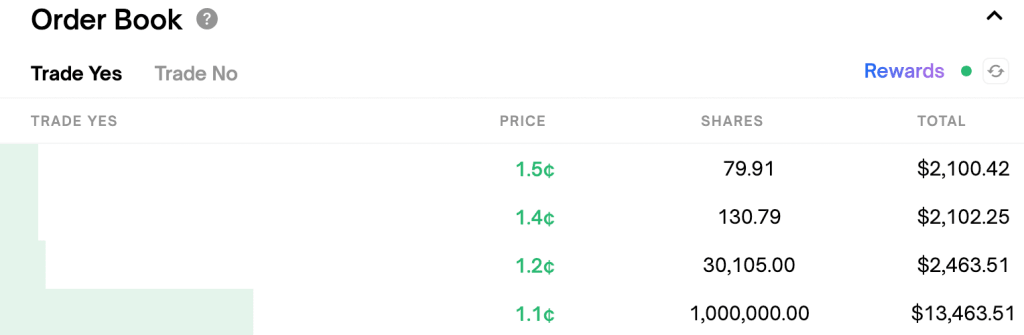

In the three days since the market opened, traders have wagered over $100,000 on this question. The market traded as high as 5%, and is now stably trading at 3%. Right now, if you wanted to, you could place a bet that Jesus Christ will not return this year, and earn over $13,000 if you're right.

There are two mysteries here: an easy one, and a harder one.

The easy mystery is: if people are willing to bet $13,000 on "Yes", why isn't anyone taking them up?

The answer is that, if you wanted to do that, you'd have to put down over $1 million of your own money, locking it up inside Polymarket through the end of the year. At the end of that year, you'd get 1% returns on your investment. And you can do so much better on the stock market, or even in U.S. treasury bonds.

So that's why no one is buying the market down to 1%. But the real mystery is: why is anyone participating in the market on the "Yes" side? Like, who is betting that Jesus will return this year, and why?

Here are a few answers I came up with:

- [True Believers] Maybe these people really believe that there's a 3% chance that Christ will return this year!

- [Incorrect Resolution] Maybe the "Yes" people are betting that the market will be resolved incorrectly (that there's a 3% chance that the market will resolve "Yes" even though Christ will not return in 2025).

- [The Memes] Maybe the "Yes" people are buying "Yes" for the lulz. It's kinda fun to tell people that you bet that Jesus Christ would return this year!

But none of these hypotheses ring true to me:

- The True Believers hypothesis rings false because that would be a frankly ridiculous belief to hold. Sometimes people profess ridiculous things, but very few of them put their money where their mouth is on prediction markets.[1]

- The Incorrect Resolution hypothesis rings false because, while there's some chance of an incorrect resolution, it's really unlikely to be as high as 3%. Polymarket has a lot of reputation to lose by incorrectly resolving this market, and would almost certainly override its consensus-based resolution mechanism if it came to that.

- The Memes hypothesis is more plausible, but I think ultimately false. Several people have spent hundreds of dollars betting yes, which is a lot of money to spend for the memes.

So I asked my friend Jesse, who trades on Polymarket, and he had a pretty interesting theory:

- [Time Value of Money] The Yes people are betting that, later this year, their counterparties (the No betters) will want cash (to bet on other markets), and so will sell out of their No positions at a higher price.

In other words: right now, there's not much interesting stuff happening on Polymarket. People are spending a lot of money betting on sports, but not much else. But at some point in 2025, other markets will get a lot of attention. The New York mayoral election is happening this year. Pope Francis is in poor health, so there may be a new pope this year. God forbid China invade Taiwan, but such an invasion would result in many interesting markets. Right now, all these markets have mere single-digit millions of dollars in trading volume, but that could very easily change.

And if it changes, some of the people betting No on Christ's return will want to unlock that money -- that is, sell their "No" shares -- so that they can use it to bet on other markets. If enough people want to sell their "No" shares, the "Yes" holders may be able to sell out at an elevated price, like 6%, potentially getting a 2x return on their investment!

The Time Value of Money hypothesis posits that the Yes bettors are more sophisticated than they look. In finance, time value of money is the idea that a dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow, because you can do things with that dollar, such as making bets. The Yes traders are betting that the time value of Polymarket cash will go up unexpectedly: that other traders will be short on cash to place bets with, and will at some point be willing to pay a premium to free up the cash that they spent betting against Jesus.

Has this galaxy-brained trade ever gone well? Yes! In late October of last year -- a week before the election -- Kamala Harris was trading around 0.3% in safe red states like Kentucky, while Donald Trump was trading around 0.3% in safe blue states like Massachusetts. On election day, these prices skyrocketed to about 1.5%, because "No" bettors desperately needed cash to place other bets on the election. Traders who bought "Yes" for 0.3% in late October and sold at 1.5% on election day made a 5x profit! This means that even though Harris only had a 0.1% chance[2] of winning Kentucky, the "correct" price for the Kentucky market to trade at was more like 1.5%.

This means that the Jesus Christ market is quite interesting! You could make it even more interesting by replacing it with "This Market Will Resolve No At The End Of 2025": then it would be purely a market on how much Polymarket traders will want money later in the year.[3] As long as there is disagreement about the future time value of Polymarket cash, there will be trades, and then trading price will be above zero. The more that traders expect to want cash later in the year, the higher the market will trade.

(If Polymarket cash were completely fungible with regular cash, you'd expect the Jesus market to reflect the overall interest rate of the economy. In practice, though, getting money into Polymarket is kind of annoying (you need crypto) and illegal for Americans. Plus, it takes a few days, and trade opportunities often evaporate in a matter of minutes or hours! And that's not to mention the regulatory uncertainty: maybe the US government will freeze Polymarket's assets and traders won't be able to get their money out?)

What kinds of years see a high time value of Polymarket cash? Election years. As late as June, Polymarket had Democrats with a 6.5% chance of winning Kentucky (and this was typical of the safe states), even though the actual probability was more like 1%.[4] This means that traders were forgoing a relatively safe 16% annualized return, just so that they could have cash now to make other bets with! If there had been a "will Christ return in 2024" market, I bet it would have traded higher than 3% around this time last year: maybe more like 5%.

And so, you heard it here first: Jesus Christ will probably return in an election year (at least if you believe the prediction markets)!

- ^

I’ve seen some pretty mispriced markets. At one point in 2019, PredictIt had Andrew Yang at 16% to win the Democratic presidential primary. And in 2020, Donald Trump was about 16% to become president even after he had lost the election. But the sorts of people who bet on prediction markets are not the sorts of fundamentalist Christians who think that Jesus Christ has a high chance of returning this year.

- ^

So says Nate Silver’s model in late October, and I agree.

- ^

Jesse points out that “the Jesus market should trade really low” is potentially a really good metric for evaluating the efficiency of prediction markets, and that prediction markets should aim to structure their mechanisms in a way that makes markets like this one trade really low. Manifold Markets has experimented with giving out loans for basically this purpose, although this seems much safer to do with fake money than real money.

- ^

After the election, Polymarket changed the labels from “Democrat” and “Republican” to “Harris” and “Trump”, but the labels said “Democrat” and “Republican” at the time.

It's unclear how this market would resolve. I think you meant something more like a market on "2+2=5"?

I don't think there's a way to resolve it? It will basically always be a prediction on the reliability of the statement.