Introduction

Insight meditation, enlightenment, what’s that all about?

The sequence of posts starting from this one is my personal attempt at answering that question. It grew out of me being annoyed about so much of this material seeming to be straightforwardly explainable in non-mysterious terms, but me also being unable to find any book or article that would do this to my satisfaction. In particular, I wanted something that would:

- Explain what kinds of implicit assumptions build up our default understanding of reality and how those assumptions are subtly flawed. It would then point out aspects from our experience whose repeated observation will update those assumptions, and explain how this may cause psychological change in someone who meditates.

- It would also explain how the so-called “three characteristics of existence” of Buddhism - impermanence, no-self and unsatisfactoriness - are all interrelated and connected with each other in a way your average Western science-minded, allergic-to-mysticism reader can understand.

I failed to find a resource that would do this in the way I had in mind, so then I wrote one myself.

From the onset, I want to note that I am calling this a non-mystical take on the three characteristics, rather than the non-mystical take on the three characteristics. This is an attempt to explain what I personally think is going on, and to sketch out an explanation of how various experiences and Buddhist teachings could be understandable in straightforward terms. I don’t expect this to be anything like a complete or perfect explanation, but rather one particular model that might be useful.

The main intent of this series is summarized by a comment written by Vanessa Kosoy, justifiably skeptical of grandiose claims about enlightenment that are made without further elaboration on the actual mechanisms of it:

I think that the only coherent way to convince us that Enlightenment is real is to provide a model from a 3rd party perspective. [...] The model doesn't have to be fully mathematically rigorous: as always, it can be a little fuzzy and informal. However, it must be precise enough in order to (i) correctly capture the essentials and (ii) be interpretable more or less unambiguously by the sufficiently educated reader.

Now, having such a model doesn't mean you can actually reproduce Enlightenment itself. [...] However, producing such a model would give us the enormous advantages of (i) being able to come up with experimental tests for the model (ii) understanding what sort of advantages we would gain by reaching Enlightenment (iii) being sure that your are talking about something that is at least a coherent possible world even if we are still unsure whether you are describing the actual world.

I hope to at least put together a starting point for a model that would fulfill those criteria.

Note that these articles are not saying “you should meditate”. Getting deep in meditation requires a huge investment of time and effort - though smaller investments are also likely to produce benefits - and is associated with its own risks [1 2 3 4]. My intent is merely to discuss some of the mechanisms involved in meditation and the mind. Whether one should get direct acquaintance with them is a separate question that goes beyond the scope of this discussion.

Briefly on the mechanisms of meditation

In a previous article, A Mechanistic Model of Meditation, I argued that it is possible in principle for meditation to give people an improved understanding of the way their mind operates.

To briefly recap my argument: we know it is possible for people to train their senses, such as learning to notice more details or make more fine-grained sensory discriminations. One theory is that those details have always been processed in the brain, but the information has not made it to the higher stages of the processing hierarchy. As you repeatedly focus your attention to a particular kind of pattern in your consciousness, neurons re-orient to strengthen that pattern and build connections to the lower-level circuits from which it emerges. This re-encodes the information in those circuits in a format which can be represented in consciousness.

This means at least some kinds of sensory training are training in introspection - learning to better access information which already exists in your brain. This implies you can also learn to strengthen other patterns in your consciousness, especially if you have some source of feedback that you can use to guide the training.

I gave an example of experiential forms of therapy doing exactly this, and then described how a particular style of meditation used one’s awareness of the breath as an objective feedback signal for developing increased “introspective awareness” of one’s own mind.

That post was mostly describing the ways in which meditation can be used to become more aware of the content of your thoughts. However, in observing the content, it is hard to avoid noticing at least some of the structure of the thought process as well.

For example, you might try to follow your breath and think you are doing a good job. In this case, there are at least two kinds of content in your mind: the actual sensory experience of the breath, and thoughts about how badly or well you are doing. The latter might take the form of e.g. mental dialogue that says things like "I'm still managing to follow my breath". Now, since you may find it rewarding to just think that you are meditating well, that thought may start to become rewarded, and you may find yourself repeatedly thinking that you are successfully following the breath... even as the thought of “I am meditating well” has become self-sustaining and no longer connected to whether you are following the breath or not.

Eventually you will realize that you have actually been thinking about following the breath rather than actually following it. This is a minor insight into the way that your thought processes are structured, revealing it is possible for sensations and thoughts about sensations to become mixed up.

It is also possible to practice meditation in a way which explicitly focuses on investigating structure. We can make an analogy to looking at a painting. (Thanks to Alexei Andreev for suggesting this analogy.) Seen from some distance, a painting has "content": it depicts things like people, buildings, boats and so forth. But when you get closer to it and look carefully, you can see that all the content is composed of things like brush strokes, individual colored shapes, paint of varying thickness, and so on. This is "structure". While all types of meditation are going to reveal something about structure, there are also types of meditation which are specifically aimed at exploring it. Meditation which focuses on investigating structure is commonly called insight meditation.

Investigating the mind vs. investigating reality

Now, it is worth noting that these practices are not always framed in terms of "investigating the structure of the mind", nor does the actual experience of doing them necessarily feel like that. Rather, the framing and experience is commonly that of investigating the nature of reality.

For example, in an earlier article trying to explain insight meditation, I mentioned I had once had the thought that I could never be happy. When I paid closer attention to why I thought that, I noticed that my mental image of a happy person included strong extraversion, which conflicted with the self-image that I had of myself as an introvert. After I noticed the happiness-extraversion connection, it became apparent that I could be happy even as an introvert, and the original thought disappeared. (Although I didn't know it at the time, it is common for emotional beliefs to change when they become explicit enough for the brain to notice them being erroneous.)

Essentially, I had originally believed “I can never be happy”, and this belief about me didn’t feel like a “belief”. It felt like a basic truth of what I was, the kind of truth that you just know - in the same way that you might look at an apple and just know you are having the experience of seeing an apple. But when I investigated the details of that experience, I realized that this wasn’t actually a fact about me. Rather it was just a belief that I had.

In a similar way, there are many aspects of our subjective experience that feel like facts about reality, but upon doing insight practices and investigating them closer, we can come to see that they are not so.

The philosopher Daniel Dennett has coined the term "heterophenomenology" to refer to a particular approach to the study of consciousness. In this approach, we assume that people are correctly describing how things seem to them and treat this as something that needs to be explained. However, the actual mechanism of why things seem like that to them, may be different from what they assume.

If I see an apple, it typically feels to me like I am seeing reality as it is. From a scientific point of view, this is mistaken: the sight of an apple is actually a complex interpretation my brain has created. Likewise, if I have the experience that I can never be happy, then this also feels like a raw fact while actually being an interpretation. In either case, if I manage to do practices which reveal my interpretation to be flawed, they will subjectively feel like I am investigating reality... while from a third-person perspective, we would rather say that I am investigating the way my mind builds up reality.

It is valid to stick to just the first-person experience of investigating reality directly. Many of these practices are framed solely in those terms, because a stance of curiosity and having as few assumptions as possible is the best mindset for actually doing the practices. But if one says that meditation investigates the nature of reality, then it becomes hard to test the claim from a third-person perspective. A common criticism is that meditation certainly changes how people experience the world, but it might just as well be loosening their grasp on reality.

On the other hand, if we provisionally assume that meditation works by revealing how the mind structures its model of reality, then we can check whether the kinds of insights that people report are compatible with what science tells us about the brain. If it turns out that meditators doing insight practices are coming up with experiences that match our understanding of actual brain mechanisms, then the practices might actually provide insight rather than delusion. In cases where no scientific evidence is yet available, it should at least be possible to construct a model that could be true and compatible with the third-person evidence.

In previous posts, I have explored some scientifically-informed models of the brain, which I think are naturally linked to the kinds of discoveries made in insight meditation. This article will more explicitly connect concepts from the theory of meditation to those kinds of models.

It is also worth noting that I think both claims about meditative insights are true: some things you can do with meditation do give you a better insight into reality, while some other things do just break your brain and reduce your contact with reality. (A fact responsible meditation teachers also warn about.) This makes it important to have third-person models of what could be a genuine insight and what is probably delusion, to help avoid the dangerous territory.

My multiagent model of mind

I have been calling my interpretation of those models a “multiagent model of mind”. What follows is a highly abridged version of it; see the linked index of posts for much more extensive discussion, including the sources that I have been drawing on for my synthesis.

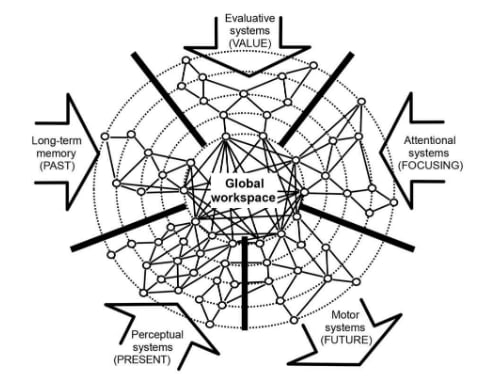

One of the main ideas of the multiagent model is that the brain contains a number of different subsystems operating in parallel, each focusing on their own responsibilities. They share information on a subconscious level, but also through conscious thought. The content of consciousness roughly corresponds to information which is being processed in a “global workspace” - a “brain web” of long-distance neurons, which link multiple areas of the brain together into a densely interconnected network.

The global workspace can only hold a single piece of information at a time. At any given time, multiple different subsystems are trying to send information into the workspace, or otherwise modify its contents. Experiments show that a visual stimuli needs to be shown for about 50 milliseconds for it to be consciously registered, suggesting that the contents of consciousness might be updated at least 20 times per second. Whatever information makes it into consciousness will then be broadcast widely throughout the brain, allowing many subsystems to synchronize their processing around it.

The exact process by which this happens is not completely understood, but involves a combination of top-down mechanisms (e.g. attentional subsystems trying to strengthen particular signals and keep those in the workspace) as well as bottom-up ones (e.g. emotional content getting a priority). For example, if you are listening to someone talk in a noisy restaurant, both their words and the noise are bottom-up information within the workspace, while a top-down process tries to pick up on the words in particular. If a drunk person then suddenly collides with you, you are likely to become startled, which is a bottom-up signal strong enough to grab your attention (dominate the workspace), momentarily pushing away everything else.

There is also a constant learning process going on, where the brain learns which subsystems should be given access in which circumstances, while the subsystems themselves also undergo learning about what kind of information to send to consciousness.

When I talk about “subsystems” sending content into consciousness, I mean this as a very generic term, which includes all of the following:

- Literal subsystems, e.g. information from the visual, auditory, and other sensory systems

- Subpatterns within larger subsystems, e.g. a particular neuronal pattern encoding a specific memory or habit

- Emotional schemas which trigger in particular situations and contain an interpretation of that situation and a response

- Working memory buffers associated with type 2 (“System 2”) reasoning, helping chain the outputs of several different subsystems together

In some cases, I might talk about there being two separate subsystems, when one could argue that this would be better described as something like two separate pieces of data within a single subsystem. For example, I might talk about two different memories as two different subsystems, when one could reasonably argue that they are both contained within the same memory subsystem. Drawing these kinds of distinctions within the brain seems tricky, so rather than trying to figure out what term to use when, I will just talk about subsystems all the time.

Epistemic status

Buddhist theories of the mind are based on textual traditions that purport to record the remembered word of the Buddha, on religious and philosophical interpretations of those texts, and on Buddhist practices of mental cultivation. The theories aren’t formulated as scientific hypotheses and they aren’t scientifically testable. Buddhist insights into the mind aren’t scientific discoveries. They haven’t resulted from an open-ended empirical inquiry free from the claims of tradition and the force of doctrinal and sectarian rhetoric. They’re stated in the language of Buddhist metaphysics, not in an independent conceptual framework to which Buddhist and non-Buddhist thinkers can agree. Buddhist meditative texts are saturated with religious imagery and language. Buddhist meditation isn’t controlled experimentation. It guides people to have certain kinds of experiences and to interpret them in ways that conform to and confirm Buddhist doctrine. The claims that people make from having these experiences aren’t subject to independent peer review; they’re subject to assessment within the agreed-upon and unquestioned framework of the Buddhist soteriological path. [...]

I’m not saying that Buddhist meditative techniques haven’t been experientially tested in any sense. Meditation is a kind of skill, and it’s experientially testable in the way that skills are, namely, through repeated practice and expert evaluation. I have no doubt that Buddhist contemplatives down through the ages have tested meditation in this sense. I’m also not saying that meditation doesn’t produce discoveries in the sense of personal insights. (Psychoanalysis can also lead to insights.) Rather, my point is that the experiential tests aren’t experimental tests. They don’t test scientific hypotheses. They don’t provide a unique set of predictions for which there aren’t other explanations. The insights they produce aren’t scientific discoveries. [...]

I’m also not trying to devalue meditation. On the contrary, I’m trying to make room for its value by showing how likening it to science distorts it. Meditation isn’t controlled experimentation. Attention and mindfulness aren’t instruments that reveal the mind without affecting it. Meditation provides insight into the mind (and body) in the way that body practices like dance, yoga, and martial arts provide insight into the body (and mind). Such mind-body practices—meditation included—have their own rigor and precision. They test and validate things experientially, but not by comparing the results obtained against controls.

-- Evan Thompson, Why I Am Not A Buddhist

I think it is reasonable to believe that meditation can give us genuine insights into the way the mind functions. The meditative techniques and practices which I am drawing upon in this series have been developed within Buddhist traditions, and I make frequent references to the theory developed within those traditions.

At the same time, while I am drawing upon theories developed within these traditions, I am treating those as a source of inspiration to be critically examined, rather than as sources of authority.

For one, there are many different Buddhist theories and schools that disagree with each other, many of them claiming to teach what the Buddha really meant. And as e.g. Evan Thompson’s book discusses, one cannot cleanly separate Buddhist meditative techniques from Buddhist religious teaching. People who meditate using those techniques - myself included - do so while being guided by an existing conceptual framework, framing their experiences in light of their framework. Practitioners who use different kinds of techniques and frameworks end up drawing different conclusions: e.g. some frameworks end up at the conclusion that no selves exist, while others end up believing that everything is self. (The extent to which this difference in framing actually leads to a different experience is unclear.) Many of these frameworks also draw upon supernatural elements, such as claims of rebirth and remembering past lives.

Still, many meditation teachers also say things along the lines of “you should not take any of this on faith, just try it out and see for yourself”. Personally I started out skeptical of many claims, dismissing them as pre-scientific folk-psychological speculation, before gradually coming to believe in them - sometimes as a result of meditation which hadn’t even been aimed at investigating those claims in particular, but where I thought I was doing something completely different. And it seems to me that many of the meditative techniques actively require you to suspend your expectations in order to work properly, requiring you to look at what’s present rather than at the thing you expect to see.

So, like many others, I simultaneously believe that i) meditative techniques point at genuine insights and also produce them in the minds of people who meditate and also that ii) we should not put excess faith in the claims of the existing meditation traditions. As many teachers encourage exactly this line of thought - as in the comment of taking nothing on faith - this feels like an appropriate spirit for approaching these matters.

Rather than trying to be authentically Buddhist, this article is concerned with building a model of the neural and psychological mechanisms I think the three characteristics are pointing at, even if that model ends up sharply deviating from the original theories. I heavily draw on my own experiences and the experiences and theories of other people whose reports I have reason to trust. I proceed from the assumption that regardless of whether the original frameworks are true or false, they do systematically produce similar effects and insights in the minds of the people following them, and that is an observation which needs to be explained.

In fact, I am happy to mix and match examples, exercises, interpretations and results drawn from all of the contemplative traditions that I happen to have any familiarity with, with current-day Western psychology and psychotherapy thrown in for good measure. They may have different approaches, but to the extent that they share commonalities, those commonalities tell us something about what human minds might have in common. And to the extent that they differ, one tradition might be pointing out aspects about the human mind that the others have neglected and vice versa, as in the fable of the blind men and the elephant.

Current articles in this series:

- Introduction and preamble (you are here)

- A non-mystical explanation of "no-self"

- Craving, suffering, and predictive processing

- From self to craving

- On the construction of the self

- Impermanence

Thank you to Alexei Andreev, David Chapman, Eliot Re, Jacob Spence, James Hogan, Magnus Vinding, Max Daniel, Matthew Graves, Michael Ashcroft, Romeo Stevens, Santtu Heikkinen, and Vojtěch Kovařík for valuable comments. None of the people in question necessarily agree with all the content in this or the upcoming posts; much of the content has also been rewritten after the drafts that most of them saw.

I would offer the following in an attempt to provide you with some benefit and urge a bit more compassion for yourself along this line of thought, although I can relate to your comment about craving masquerading as noble intention. I'm a lay buddhist, although I have thought about becoming a Monk at certain points in my life. My point is I can't lay claim to an explanation of why I put it the way I did as being 'the correct way', with any strong appeal to credibility due to perfect lineage transmission.

But I can give you my thinking based on my studies and experience, and try to explain why I think it is both the meditation practice and the 'wound' you were referring to, but that it is the meditation practice that may be "at fault" for lack of a better phrase. A great thing about Buddhism is that in many ways it allows us to place the blame for our problems within the world instead of within ourselves, thereby removing a lot of unhelpful guilt in a Moral sense.

That's not to say we shouldn't work to correct our faults, only that they aren't really our fault despite being in us. They are ours because they are in us, but we didn't cause them, the world did. This is my opinion, but it is what I like about Buddhism in comparison to say Christiantiy, in which it is the original sin or Adam and Eve which caused all of humanities downfall, and it is my sinful nature (strong emphasis on appealing to a very subjective Moral authority) which is my problem. Without Jesus I'm lost, and the ideas about Good and Evil are very black and white. Plus, there is a strong correlation in many churches between Moral Superiority and Financial Wellbeing. If you are poor or out of work, it's implied you are a moral failure, and either lazy or too stupid to know how to pull your self out of poverty. The moral status of the individual is the anchor point around which the entire world orbits, whether you are at the top of the heap or the bottom.

In Buddhism I find there is less of a correlation between 'Goodness' and 'money.' If you have money you can still be a horrible person, and if you are poor, you can still be a good person. From my perspective having lived in the shelter system for around 4 years now, and having grown up in poverty, Western tradition really seems to revolve around this tight relationship between Goodness and financial prosperity being divinely linked. I think this is a flaw in society. Without going into it too much, Eastern culture also equates money with Goodness in many ways, but I think there is more acceptance that poverty isn't necessarily caused by poor people making immoral choices, society is just a corrupting force.

One of the great things, from a Buddhist perspective, about being a human is the ability to come into contact with the Dharma. As a rock, or an animal, we couldn't benefit from the Dharma really, as we wouldn't have the facilities to understand it or practice it, but as humans we can. In this day and age it is even easier to come into contact with it, it's all over the Internet, and many more communities today have some sort of Buddhist center. It's gotten so much simpler to come into contact with it today than it was when I was a kid, before the Internet. I had to ride an hour and a half each way to get to a library which may or may not have a 20 year old book on Buddhism on the shelf. Most of my books early on I got from Borders or from academic libraries because there was no where else to get them. I had to spend a huge amount of time and energy to find Dharma, but these days it's a completely different story.

Being a human allows us to understand the causes of suffering, and to learn to practice to alleviate it, as long as we have access to the Dharma. Animals and people without access to the Dharma are unlikely to understand the causes of suffering and be able to learn to practice to alleviate it, so by being human and having access to it, we are very lucky. At least according to Buddhist thinking. I tend to agree, otherwise I wouldn't practice or study it.

A downside to having all this access to Dharma through mediums like the Internet and academic institutions though, is that in addition to presenting wisdom and knowledge from the entire spectrum of Buddhist traditions, there is all the information from all the non-Buddhists who have pulled ideas, concepts and practices from Buddhist tradition and attempted to 'translate' them into more modern and more 'effective' versions. There's a lot of mis and disinformation about the Dharma floating around out there.

So maybe closer to the point, finding and developing a healthy relationship with an experienced teacher isn't as easy as finding the Dharma. This is also not our fault. So while we might have it at our finger tips, without a good guide, we won't know what have or how to use it well. Even if we read and learn on our own, we are likely to make a lot of mistakes because we are flawed in our perceptions - not necessarily in a moral way though. We aren't 'bad', just confused and ignorant, blinded by illusion.

But the Dharma isn't as easy to use as something like Netflix on the Internet. We can't download it or stream it and expect it to work similarly. We can't read about it and expect to understand it without help. We can't practice it and expect not to make mistakes. We can't pass on what we don't have either. Which is why a teacher is so important. If we want to benefit from Yoga, we have to practice it, not just study it. If we don't have a good teacher, we may practice it wrong and hurt ourselves.

Academic institutes can be a mixed bag. Surveys of 'all' Buddhist teachings and practices I think, like most aggregate sets of diverse information, tend to want a one size fits all solution to whatever ails you. Practicing based on selecting for benefits while avoiding as much of the 'downsides' as possible, isn't really possible in reality. Hoping to come up with a lowest common denominator approach to utilizing the 'strengths of a diverse selection' of practices tends to remove most cultural, social and historic context which I jokingly refer to as a sort of 'American Cheesination' of non american cultural practices.

American cheese is probably the most unhealthy and bad tasting of all cheeses, simply because it is so heavily processed. Corporate America (and therefore the average American) loves this approach of trying to create benefit while trying to avoid side effects for instance. This has lead to a number of issues with consumer health, and is the concern of the FDA and how it regulates/misregulates food and drugs. The fallacy goes like this: 'we' want the flavor Fat offers in our foods without the actual Fat - which is what created Olestra - and we want the sweetness and energy of sugar without the calories - which created a whole slew of artificial sweetenters and sugar substitutes.

These attempts to scientifically synthesize a desirable product without the associated 'down sides' simply led to a shift in the types of 'down sides' the new product has. The disgusting and painful side effects of Olestra meant it was pulled from the market, and personally I can't stand artificial sugar, I won't buy a product if it contains it, and I'm pretty sure most people who say they like the taste are lying.

All joking aside, specific Buddhist traditions and practices tend to have a consistency to them, that allows you to check your own experience of your practice against a long history of other practitioners experiences. Basically the practices have been around a long long time, which is something modern versions of meditation and psychotherapies which incorporate it, or modern highly processed foods tend to lack; Cultureless Culture, Fatless Fats and Sugarless Sugars just don't have a long history of successful benefit to humanity.

That's not to say modern science doesn't have a lot of data to pull from, only that most of the data doesn't go back all that far, maybe a few hundred years at most concerning issues like consciousness and the assorted phenomenon. And despite the fact, or possibly because, there is so much data to sort through - of varying quality and often incredibly sparse distribution across the entire spectrum of human experience - modern regulatory bodies and scientific communities don't seem to be able to come to many decent conclusions about what the 'truth' is regarding healthy diet, healthy lifestyles, or healthy psychological makeup or cultural practice.

Which brings us back to mental health and any possible benefits to meditation. Everybody has 'wounds' of the type I think you are referring - after all a central tenet to most if not all Buddhist practice and thinking is that "life is suffering" and wounds whether physical, emotional or psychological represent a type of suffering - so this is not really the solvable problem IMO. To just not have any 'wounds' is impossible, even the most well adjusted person in the world experiences suffering, so simply living life unwounded isn't a reality.

But since we all suffer from 'the illusion of self'- the compounded wounds, biases, and limitations of perception and understanding which make us human and not omniscient gods - it is this which is 'the barrier' to knowing the truth. Having 'wounds' (suffering) is a universal characteristic of all life, as all life suffers; it is the selection and practice of solutions which is the area Buddhist practice focus on, not necessarily the belief that our 'wounds' are the problem. Wounds are a fact of life, not an optional factor of life. If it were optional, none of us would probably choose to be wounded or to have biases or emotional or psychological issues, but then we wouldn't be human either.

So it's the lack of, and/or incorrect selection of 'correct' ways to deal with our 'wounds' where real progress can be made or abandoned. Different types of meditations have different effects, and different people have different 'wounds', or what others might term cognitive distortions, or still others might term biases, beliefs, habits,etc. There are many many ways people are deluded from 'truth', many ways that 'life is an illusion' so this should not be the point of contention I think.

"But there is a path to cessation of suffering" which means there are solutions, and "it is the Dharma." means knowing and practicing 'the truth' is the solution. The question is actually then, "what is the Dharma and how do we practice it?" (This is the concern of many Buddhist traditions and practices, of which meditation is part.) So the 'problem' becomes how to choose which practices to select, of which meditation is just one type of practice, and how to know if we are practicing them correctly. This is where a qualified teacher becomes invaluable.

Most people want to meditate, because they believe this is where the true benefit comes from. I believe there are many benefits to meditation, but there are other practices as well. In some cases though, there are advanced types of meditation. Like advanced classes in college, Advanced Meditations have prerequisites. These meditations are many of the meditations that involve culturally specific ideas, concepts and practices and can vary widely from sect to sect. This is where mistranslations can have negative effects, and where attempts to gain the benefits of these practices without accruing the associated 'down sides' simply results in the shifting of the downsides to some other facet of your personality or identity, not the elimination of the downsides.

These are just some examples of a model of Social Physics I'm working on, as it appears to be the case that in modern attempts to derive benefit without downsides from processed products and practices, the downsides are simply shifted - the benefits and downsides are entangled such that you can't have one without the other. For every action there is an equal but opposite reaction - for every benefit you create, there is an equal but opposite downside created. (Also I think this involves the conservation of energy and mass - if you replace energy with benefit, and mass with downside. So the conservation of benefit and downside. But this is still a theory in development.)

I think the same is true of understanding our minds, and trying to put those understandings into action. Our actions have consequences for ourselves and others - and I think humans are particularly bad at understanding the 'correct way' of applying those filters to our lives. Often when I have concern for myself, it would be more 'correct' to have more concern for others, and vice versa. So that the type of emotional wound you are referring to has an affect on how we perceive our relationship to the world around us, including other people, and the 'distorting' effect those 'flaws' in our perception have is actually more complicated than most people consider when responding to the world viewed through a lens with such a compounded wound.

Not only is there 'distortion' in the ways we perceive the world through the lens that contains the emotional wound or bias, there is distortion in the way that experience is encoded into our neurology in the form of different types of ideas and concepts about the world being 'modeled' in our minds, which are in turn consolidated into 'flawed' memories. The longer we rely on these 'flawed' neural loops, the more they influence the growth and construction of our central nervous system, and consequently our peripheral nervous system, so that they get 'encoded' into our emotional 'brains' and into our muscle memory, resulting in emotional and physical and/or behavioral 'disorders.' I study trauma as well, and it's the physicality of the source of the these disturbances which I think is sometimes counterintuitive to people who think 'it's all in their heads.' It's not, it's all throughout our bodies.

These distortions can become particularly problematic when we start examining our selves through lenses that come from other cultures, like Buddhist type meditations as they spread through non-buddhist communities. The traditional eastern approaches to dealing with the common disturbances to the practitioners 'system', typically involve frameworks which develop to help explain what's going on (chakras, Chi, Qi, etc. etc) but become wild cards of sorts if there isn't anyone in the non-buddhist practitioners community with the social, cultural and historical practice or experience to make cross cultural interpretations of the 'mystic, esoteric' stuff in the non-Buddhist community.

These frameworks are often meant to be 'safety valves' designed to create literal neural structure along 'correct' neural loops, through repeated adherence to rules of conduct: right thought, right action, right speech, or any of the other practices meant to train the practitioners Peripheral Nervous System/Central Nervous System to be able to safely handle the possible disruptions to the practitioners sense of self, community, and conceptual relationship to the real world. This can often result from the changing of thoughts, actions, and speech caused by attempts to 'polish the flaws out of our lenses of perception' through practices like meditation. A bit like having a new pair of powerful glasses, it takes us awhile to get used to new ways of seeing the world.

In particular Insight meditation can cause exactly this type of change in perception, because it introduces us to new, sometimes alien concepts which might cause paradigm shifts in our thinking. These concepts like 'no self', 'illusion of self', 'enlightenment', 'nirvana', 'karma' and so on, tend to be integral parts of Insight meditation and by integrating them into our understanding of ourselves and our world, we run the risk of misunderstanding them, and so 'scratching the lens' and making the flaws worse instead of 'polishing them' and making our perceptions more accurate.

IMO the Universe as perceived by humans is flawed, but despite the fact that the flaws are in our perception of the Universe and not in the Universe itself, it is not our faults that we misperceive it. If we have access to the Dharma, but don't practice it, then I think it is possible to accept more of the blame for our faults and how we negatively effect the world. And this is where the guilt trip comes in. Once you know the truth, if you don't act on it, you better have a good reason. If you don't know the truth though, it's difficult to assume responsibility for not working for it or towards it. However, if you actively hide from or ignore the truth, that's where some real problems start I think.