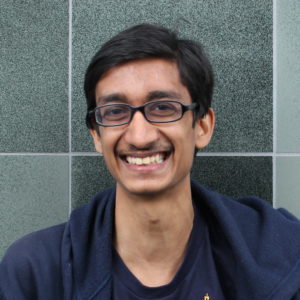

I along with several AI Impacts researchers recently talked to talked to Rohin Shah about why he is relatively optimistic about AI systems being developed safely. Rohin Shah is a 5th year PhD student at the Center for Human-Compatible AI (CHAI) at Berkeley, and a prominent member of the Effective Altruism community.

Rohin reported an unusually large (90%) chance that AI systems will be safe without additional intervention. His optimism was largely based on his belief that AI development will be relatively gradual and AI researchers will correct safety issues that come up.

He reported two other beliefs that I found unusual: He thinks that as AI systems get more powerful, they will actually become more interpretable because they will use features that humans also tend to use. He also said that intuitions from AI/ML make him skeptical of claims that evolution baked a lot into the human brain, and he thinks there’s a ~50% chance that we will get AGI within two decades via a broad training process that mimics the way human babies learn.

A full transcript of our conversation, lightly edited for concision and clarity, can be found here.

By Asya Bergal

I was already interpreting your comment as "if you deploy a dangerous AI system, that affects you too". I guess I'm just not sure your condition 2 is actually a key ingredient for the MAD doctrine. From the name, the start of Wikipedia's description, my prior impressions of MAD, and my general model of how it works, it seems like the key idea is that neither side wants to do the thing, because if they do the thing they get destroyed to.

The US doesn't want to nuke Russia, because then Russian nukes the US. This seems the same phenomena as some AI lab not wanting to develop and release a misaligned superintelligence (or whatever), because then the misaligned superintelligence would destroy them too. So in the key way, the analogy seems to me to hold. Which would then suggest that, however incautious or cautious society was about nuclear weapons, this analogy alone (if we ignore all other evidence) suggests we may do similar with AI. So it seems to me to suggest that there's not an important disanalogy that should update us towards expecting safety (i.e., the history of MAD for nukes should only make us expect AI safety to the extent we think MAD for nukes was handled safely).

Condition 2 does seem important for the initial step of the US developing the first nuclear weapon, and other countries trying to do so. Because it did mean that the first country who got it would get an advantage, since it could use it without being destroyed itself, at that point. And that doesn't apply for extreme AI accidents.

So would your argument instead be something like the following? "The initial development of nuclear weapons did not involve MAD. The first country who got them could use them without being itself harmed. However, the initial development of extremely unsafe, extremely powerful AI would substantially risk the destruction of its creator. So the fact we developed nuclear weapons in the first place may not serve as evidence that we'll develop extremely unsafe, extremely powerful AI in the first place."

If so, that's an interesting argument, and at least at first glance it seems to me to hold up.