Orcas have about 43 billion cortical neurons - humans have about 21 billion. The orca cortex has 6 times the area of the human cortex, though the neuron density is about 3 times lower.

[...]

My uncertain guess is that, within mammalian brains, scaling matters a lot more for individual intelligence,

This post seems to assume that a 2x increase in brain size is a huge difference (claiming this could plausibly yield +6SD), but a naive botec doesn't support this.

For humans, brain size and IQ are correlated at ~0.3. Brain size has a standard deviation of roughly 12%. So, a doubling of brain size is ~6 SD of brain size which yields ~1.8 SD of IQ. I think this is probably a substantial overestimate as I don't expect this correlation is fully causal: increased brain size is probably correlated with factors that also increase IQ through other mechanisms (e.g., generally fewer deleterious mutations, aging, nutrition). So, my bottom line guess is that doubling brain size is more like 1.2 SD of IQ. This implies that doubling brain size isn't that big of a deal relative to other factors.

I think this is basically the bottom line--quite likely doubling brain size isn't very decisive, but I did a more detailed botec to get to a (sloppy) bottom line out of curiosity.

First let's account for non-brain size differences. My guess is that orcas are (median) around -4 SD on non-brain size differences (aka brain algorithms) with respect to research tasks (putting some weight on language specialization, accounting for orca specialization, etc.), for an overall estimate of -2.8 SD. This doesn't feel crazy to me?

Where does this -4 SD come from? My guess is that the human-chimp gap in non-brain size improvements is around 2.2 SD[1] and the chimp-orca (non-brain size) gap is probably similar, maybe a bit smaller, let's say 1.8 SD. So, this yields -4 SD.

I think my 95% confidence internal for the orca algorithmic advantage (on research) is like -8 SD to -1 SD with a roughly normal distribution. (I could be argued into having a substantially lower value for the bottom of the confidence internval; -12 SD doesn't seem too crazy.)

To get a interval for IQ vs brain size effect, let's do a very charitable estimate and then use this as a 95th percentile. The maximally charitable estimate would be something like:

- Assume the correlation is more like 0.4 and is fully causal.

- Assume standard deviation of 8% so 2x is 9 SDs.

- This yields 3.6 SD of IQ per doubling.

Using this as a 95th percentile and 1.2 as my median, my 95% confidence internal is like 0.4 to 3.6 SDs per 2xing (putting aside the probability of this whole model being confused). Let's say this is distributed lognormally.

Now, let's say 95% interval on ocra brain size as 1.5 to 2.5. (With a log normal distribution.)

This yields ~5% chance of orcas being over 4SDs above humans. And ~10% chance of >2SDs. (See the notebook here.) After updating on our observations (humans appear to be running an intelligent civilization and orcas don't seem that smart), I update down by maybe 5x on both of these estimates to 1% chance of >4SDs and 2% chance of >2SDs.

Correspondingly, I'm not very optimistic about the prospects here.

I think the chimp vs human gap is probably roughly half brain size and half other (algorithmic) improvements. The brain size gap is 3.5x or 2.2 SD (using 1.2 SD / doubling). So, if the gap is half brain size and half other (algorithmic) improvements, then we'd get 2.2 SD of algorithmic improvement. ↩︎

Thanks for describing a wonderfully concrete model.

I like that way you reason (especially the squiggle), but I don't think it works quite that well for this case. But let's first assume it does:

Your estimamtes on algorithmic efficiency deficits of orca brains seem roughly reasonable to me. (EDIT: I'd actually be at more like -3.5std mean with standard deviation of 2std, but idk.)

Number cortical neurons != brain size. Orcas have ~2x the number of cortical neurons, but much larger brains. Assuming brain weight is proportional to volume, with human brains being typically 1.2-1.4kg, and orca brains being typically 5.4-6.8kg, orca brains are actually like 6.1/1.3=4.7 times larger than human brains.

Taking the 5.4-6.8kg range, this would be 4.15-5.23 range of how much larger orca brains are. Plugging that in for `orca_brain_size_difference` yields 45% on >=2std, and 38% on >=4std (where your values ) and 19.4% on >=6std.

Updating down by 5x because orcas don't seem that smart doesn't seem like quite the right method to adjust the estimate, but perhaps fine enough for the upper end estimates, which would leave 3.9% on >=6std.

Maybe you meant "brain size" as only an approximation to "number of cortical neurons", which you think are the relevant part. My guess is that neuron density is actually somewhat anti-correlated with brain size, and that number of cortical neurons would be correlated with IQ rather at ~0.4-0.55 in humans, though i haven't checked whether there's data on this. And ofc using that you get lower estimates for orca intelligence than in my calculation above. (And while I'd admit that number of neurons is a particularly important point of estimation, there might also be other advantages of having a bigger brain like more glia cells. Though maybe higher neuron density also means higher firing rates and thereby more computation. I guess if you want to try it that way going by number of neurons is fine.)

My main point is however, that brain size (or cortical neuron count) effect on IQ within one species doesn't generalize to brain size effect between species. Here's why:

Let's say having mutations for larger brains is beneficial for intelligence.[1]

On my view, a brain isn't just some neural tissue randomly smished together, but has a lot of hyperparameters that have to be tuned so the different parts work well together.

Evolution basically tuned those hyperparameters for the median human (per gender).

When you now get a lot of mutations that increase brain size, while this contributes to smartness, this also pulls you away from the species median, so the hyperparameters are likely to become less well tuned, resulting in a countereffect that also makes you dumber in some ways.

So when you get a larger brain as a human, this has a lower positive effect on intelligence, than when your species equilibriates on having a larger brain.

Thus, I don't think within species intelligence variation can be extended well to inter-species intelligence variation.

As for how to then properly estimate orca intelligence: I don't know.

(As it happens, I thought of something and learned something yesterday that makes me significantly more pessimistic about orcas being that smart. Still need to consider though. May post them soon.)

- ^

I initially started this section with the following, but I cut it out because it's not actually that relevant: "How intelligent you are mostly depends on how many deleterious mutations you have that move you away from your species average and thereby make you dumber. You're mostly not smart because you have some very rare good genes, but because you have fewer bad ones.

Mutations for increasing sizes of brain regions might be an exception, because there intelligence trades off against childbirth mortality, so higher intelligence here might mean lower genetic fitness."

Number cortical neurons != brain size. Orcas have ~2x the number of cortical neurons, but much larger brains. Assuming brain weight is proportional to volume, with human brains being typically 1.2-1.4kg, and orca brains being typically 5.4-6.8kg, orca brains are actually like 6.1/1.3=4.7 times larger than human brains.

I think cortical neurons is a better proxy than brain size and I expect that the relation between cortical neurons and brain size differs substantially between species. (I expect more similarity within a species.)

My guess is that neuron density is actually somewhat anti-correlated with brain size

This might be true in mammals (and/or birds) overall, but I'm kinda skeptical this is a big effect within humans. Like I'd guess that regression slope between brain size and cortical neurons is ~1 in humans rather than substantially less than 1.

that number of cortical neurons would be correlated with IQ rather at ~0.4-0.55 in humans

I agree you'll probably see a bigger correlation with cortical neurons (if you can measure this precisely enough!). I wouldn't guess much more though?

Overall, I'm somewhat sympathetic to your arguments that we should expect that multiplying cortical neurons by X is a bigger effect than multiplying brain size by X. Maybe this moves my estimate of SDs / doubling of cortical neurons up by 1.5x to more like 1.8 SD / doubling. I don't think this makes a huge difference to the bottom line.

Yeah I think I came to agree with you. I'm still a bit confused though because intuitively I'd guess chimps are dumber than -4.4SD (in the interpretation for "-4.4SD" I described in my other new comment).

When you now get a lot of mutations that increase brain size, while this contributes to smartness, this also pulls you away from the species median, so the hyperparameters are likely to become less well tuned, resulting in a countereffect that also makes you dumber in some ways.

Actually maybe the effect I am describing is relatively small as long as the variation in brain size is within 2 SDs or so, which is where most of the data pinning down the 0.3 correlation comes from.

So yeah it's plausible to me that your method of estimating is ok.

Intuitively I had thought that chimps are just much dumber than humans. And sure if you take -4SD humans they aren't really able to do anything, but they don't really count.

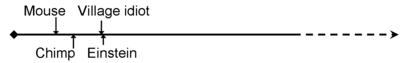

I thought it's sorta in this direction but not quite as extreme:

(This picture is actually silly because the distance to "Mouse" should be even much bigger. The point is that chimps might be far outside the human distribution.)

But perhaps chimps are actually closer to humans than I thought.

(When I in the following compare different species with standard deviations, I don't actually mean standard deviations, but more like "how many times the difference between a +0SD and a +1SD human", since extremely high and very low standard deviation measures mostly cease to me meaningful for what was actually supposed to be measured.)

I still think -4.4SD is overestimating chimp intelligence. I don't know enough about chimps, but I guess they might be somewhere between -12SD and -6SD (compared to my previous intuition, which might've been more like -20SD). And yes, considering that the gap in cortical neuron count between chimps and humans is like 3.5x, and it's even larger for the prefrontal cortex, and that algorithmic efficiency is probably "orca < chimp < human", then +6SDs for orcas seem a lot less likely than I initially intuitively thought, though orcas would still likely be a bit smarter than humans (on the way my priors would fall out (not really after updating on observations about orcas)).

Aza Raskin from the Earth Species Project is trying to translate whale language to English, by modelling whale language using an LLM, and rotating the whale LLM's embedding space to fit an English LLM's embedding space. It sounds very advanced but, as far as I know, they haven't translated anything yet. I'm not sure if they tried orcas in particular. Project CETI has also been working on sperm whales for a while but made no headlines.

That said, it does seem they all tried to understand whale language instead of teaching whales human language like your idea. There is an honest chance you'll succeed when they haven't.

If sperm whales actually are "superintelligent" after getting enough education, the benefits would be a million-fold greater than the costs.

They would be far easier to control/align than ASI because they might have human-like values to begin with, get smarter gradually, be as bribe-able as humans, and work in human-like timescales.

In conclusion, it feels very worthwhile :)

Edit:

Reasons orcas might be smarter:

- Their brains are bigger, as you said.

- They evolved a very long time with a large brain, and have algorithms better adapted to a larger brain. e.g. if you genetically engineered a chimp to have a human sized brain, it probably won't be as smart as humans because it didn't evolve long enough with a large brain.

Reasons orcas might be dumber:

- They evolved a very long time with a large brain. Paradoxically, this reason can make them dumber too. Their brains may "overfit their environment," relying more on a ton of small heuristics fine tuned for their ancestral environment, and relying less on general intelligence.

- The parts of intelligence required for tool use, engineering, and inventing, are more useful for prehistoric humans than orcas.

- Attempts to communicate haven't succeeded. This doesn't prove much because the simplest explanation is that communication is very hard, in fact many human languages can't be decoded. There's a lot of circumstantial evidence they do have language (as you mentioned in your posts).

Thanks. Yep I agree with you, some elaboration:

(This comment assumes you at least read the basic summary of my project (or watched the intro video).)

I know of Earth Species Project (ESP) and CETI (though I only read 2 publications of ESP and none of CETI).

I don't expect them to succeed in something equivalent to decoding orca language to an extent that we could communicate with them almost as richly as they communicate among each other. (Though like, if long-range sperm whales signals are a lot simpler they might be easier to decode.)

From what I've seen, they are mostly trying to throw AI at stuff and hoping somehow they will understand stuff, without having a clear plan how to actually decode it. The AI stuff might look advanced but it's sorta obvious things to try and I think it's unlikely to work very well, though still glad they are trying this.

If you look at orca vocalizations, it looks complex and alien. The patterns we can currently recognize there look very different from what we'd be able to see in an unknown human language. The embedding mapping might be useful if we had to decode a human language, and maybe we still learn some useful stuff from it, but for orca language we don't even know what their analog of words and sentences are and maybe their language works even somewhat differently (though I'd guess if they are smarter than humans there's probably going to be something like words and sentences - but they might be encoded differently in the signals than in human languages).

Though definitely plausible that AI can help significantly with decoding animal languages, but I think it also needs forming deep understanding of some things and I think it's likely too hard for ESP to succeed anytime soon, though like possible a supergenius could do it in a few years, but it would be really impressive.

My approach may fail, especially if orcas aren't at least roughly human-level smart, but it has the advantage that we can show orcas precise context of what some words and sentences mean, whereas we basically have almost no context data on recordings of orca vocalizations, so it's easier for them to see what some signals mean than for humans to infer what orca vocalizations mean. (Even if we had a lot of video datasets with vocalizations (which we don't), it's still a lot less context information about what they are talking about, than if they could show us images to indicate what they would talk about.) Of course humans have more research experience and better tools for decoding signals, but it doesn't look to me like anyone is currently remotely close, and my approach is much quicker to try and might have at least a decent chance. (I mean it nonzero worked with bottlenose dolphins (in terms of grammar better than with great apes), though I'd be a lot more ambitious.)

Of course, the language I create will also be alien for orcas, but I think if they are good enough at abstract pattern recognition they might still be able to learn it.

though I'd guess if they are smarter than humans there's probably going to be something like words and sentences

the highest form of language might be "neuralese", directly sharing your latent pre-verbal cognition. (idk how much intelligence that requires though. actually, i'd guess it more requires a particular structure which is ready to receive it, and not intelligence per se. e.g. the brain already receives neuralese from other parts of the brain. so the real question is how hard it is to evolve neuralese-emitting/-receiving structures.) also, in this framing, human language is a discrete-ized form of neuralese (standardized into words before emitting); maybe orca language would be 'less discrete' (less 'word'-based) or discrete-ized at smaller intervals (more specific 'words').

(warning: armchair evolutionary biology)

Another consideration for orca intelligence; they dodge the fermi paradox by not having arms.

Assume the main driver of genetic selection for intelligence is the social arms-race. As soon as a species gets intelligent enough (see humans) from this arms-race they start using their intelligence for manipulating the environment, and start civilization. But orcas mostly lack the external organs for manipulating the enviroment, so they can keep social-arms-racing-boosting-intelligence way past the point of "criticality".

This should be checkable, IE how long have orcas (or orca-forefathers) been socially-arms-racing? I tried asking claude to no avail, and I lack the domain knowledge to quickly look it up myself. Perhaps one could also check genetic change over time, perhaps social arms race is something you can see in this data? Do we know what this looks like in humans and orcas?

Very interesting write-up! When you say that orcas could be more intelligent than humans, do you mean something similar to them having a higher IQ or g factor? I think this is quite plausible.

My thinking has been very much influenced by Joseph Henrich's The Secret of Our Success, which you mentioned. For example, looking at the behavior of feral (human) children, it seems quite obvious to me now that all the things that humans can do better than other animals are all things that humans imitate from an existing cultural “reservoir” so to speak and that an individual human has virtually no hope of inventing within their lifetime, such as language, music, engineering principles, etc.

Gene-culture coevolution has resulted in a human culture and a human body that are adapted to each other. For example, the human digestive system is quite short because we've been cooking food for a long time, humans have muscles that are very weak compared to those of our evolutionary cousins because we've learned to make do with tools (weapons) instead and we have relatively protracted childhoods to absorb all of the culture required to survive and reproduce. If we tried to “uplift” orcas, the fact that human culture has co-evolved with the human body and not with the orca body would likely be an issue in trying to get them to learn it (a bit like trying to get software built for x86 to run on an ARM processor). Still, I think progress in LLM scaling shows that neural networks (artificial or biological) are able to absorb a significant chunk of human culture, as long as you have the right training method. I've made a similar point here.

There is nothing in principle that stops a chimpanzee from being able to read and write English, for example. It’s just that we haven’t figured out the methods to configure their brains into that state, because they don’t have a strong tendency to imitate, which human children do have, which makes training them much easier.

Considerations on intelligence of wild orcas vs captive orcas

I've updated to thinking it's relatively likely that wild orcas are significantly smarter than captive orcas, because (1) wild orcas might learn proper language and captive orcas don't, and (2) generally orcas don't have much to learn in captivity, causing their brains to be underdeveloped.

Here are the most relevant observations:

- Observation 1: (If I analyzed the data correctly and the data is correct,) all orcas currently alive in captivity have been either born in captivity or captured when they were at most 3-4 years old.[1] I think there never were any captive orcas that survived for more than a few months that were not captured at <7 years age, but not sure. (EDIT: Namu (the first captive orca) was ~10y, but he died after a year. Could be that I missed more cases where older orcas survived.)

- Observation 2: (Less centrally relevant, but included for completeness:) It takes young orcas ca 1.5 years until the calls they vocalize aren't easily distinguishable from calls of other orcas by orca researchers. (However, as mentioned in the OP, it's possible the calls are only used for long distance communication and orcas have a more sophisticated language at higher frequencies.)

- Ovservation 3: Orcas in captivity don't get much stimulation.

- Observation 4: Genie[2]. Summary from claude-3.7[3]:

- Genie, discovered in 1970 at age 13, was a victim of extreme abuse and isolation who spent her formative years confined to a small room with minimal human interaction. Despite intensive rehabilitation efforts following her rescue, Genie's cognitive impairments proved permanent. Her IQ remained in the moderate intellectual disability range, with persistent difficulties in abstract reasoning, spatial processing, and problem-solving abilities.

Her language development, while showing some progress, remained severely limited. She acquired a vocabulary of several hundred words and could form basic sentences, but never developed proper grammar or syntax. This case provides evidence for the critical period hypothesis of language acquisition, though it's complicated by the multiple forms of deprivation she experienced simultaneously.

Genie's case illustrates how early environmental deprivation can cause permanent cognitive and linguistic deficits that resist remediation, even with extensive intervention and support.

Inferences:

- If orcas need input from cognitively well-developed orcas (or richer environmental stimulation) for becoming cognitively well-developed, no orca in captivity became cognitively well-developed.

- Captive orcas could be cognitively impaired roughly similarly to how Genie was. Of course, there might have been other factors contributing to the disability of Genie, but it seems likely that abstract intelligence isn't just innate but also requires stimulation for being learned.

(Of course, it's possible that wild orcas don't really learn abstract reasoning either, and instead just hunting or so.)

- ^

Can be checked from table here. (I checked it a few months ago and I think back then there was another "(estimated) birthdate" column which made the checking easier (rather than calculating from "age"), but possible I misremember.)

- ^

Content warning: The "Background" section describes heavy abuse.

- ^

When asking claude for more examples, it wrote:

Romanian Orphanage Studies

Children raised in severely understaffed Romanian orphanages during the Ceaușescu era showed lasting deficits:

- Those adopted after age 6 months showed persistent cognitive impairments

- Later-adopted children (after age 2) showed more severe and permanent deficits

- Brain scans revealed reduced brain volume and activity that persisted into adolescence

- Cognitive impairments correlated with duration of institutionalization

The Bucharest Early Intervention Project

This randomized controlled study followed institutionalized children who were either:

- Placed in foster care at different ages, or

- Remained in institutional care

Key findings:

- Children placed in foster care before age 2 showed significant cognitive recovery

- Those placed after age 2 showed persistent IQ deficits despite intervention

- Executive functioning deficits remained even with early intervention

Isolated Cases: Isabelle and Victor

- Isabelle: Discovered at age 6 after being isolated with her deaf-mute mother, showed initial severe impairments but made remarkable recovery with intervention, demonstrating that recovery is still possible before age 6-7

- Victor (the "Wild Boy of Aveyron"): Found at approximately age 12, made limited progress despite years of dedicated intervention, similar to Genie

Of course, it's possible there's survivorship bias and actually a larger fraction recover. It's also possible that cognitive deficits are rather due to malnurishment or so.

I haven't yet read the comments to see if this issue has already been considered. I've been fascinated by non-human intelligence for many years, in particular for orcas as it seems likely that they are the most intelligent non-human life on our planet.

One area of consideration that I believe should be investigated is how brains are used. A cortical homunculus for a human shows that a great deal of human brain activity is devoted to the use of hands. e.g. manipulation of the environment. The orca lacks hands. Ergo much less brain activity devoted to environmental manipulation. What an orca does have is primary perception of the environment by sonar. This is a far more sophisticated and complex means of perception than humans possess & likely a greater driver of brain activity & processing needs.

Often, measurements of intelligence focus on "how much like us." I doubt that is a good criteria

Yeah so I actually ended up to captivated by the question and attempted to investigate it quickly in the reasoning that if they are superhumanly smart that would be very useful to figure out. But there turned out to be some annyoing constraints that makes running an experiment difficult, and I later realized that they are very probably not smarter than the smartest humans, but I still think they are likely somewhere around human level.

A key piece of information I'm missing here is how well-myelinated orca brains are compared to human brains.

A quick Google search (1) suggests that "unmyelinated axon conduction velocities range from about 0.5 to 10 m/s, myelinated axons can conduct at velocities up to 150 m/s." This seems even more significant in orcas than in humans given their larger brain and body size.

(EDIT 2025-03-15: I've added a comment which you might want to read after the post.)

Follow up to: Could orcas be smarter than humans?

(For speed of writing, I mostly don't cite references. Feel free to ask me in the comments for references for some claims.)

This post summarizes my current most important considerations on whether orcas might be more intelligent than humans.

Evolutionary considerations

What caused humans to become so smart?

(Note: AFAIK there's no scientific consensus here and my opinions might be nonstandard and I don't provide sufficient explanation here for why I hold those. Feel free to ask more in the comments.)

My guess for the primary driver of what caused humans to become intelligent is the cultural intelligence hypothesis: Humans who were smarter were better at learning and mastering culturally transmitted techniques and thereby better at surviving and reproducing.

The book "the secret of our success" has a lot of useful anecdotes that show the vast breath and complexity of techniques used by hunter gatherer societies. What opened up the possibility for many complex culturally transmitted techniques was the ability of humans to better craft and use tools. Thus the cultural intelligence hypothesis also explains why humans are the most intelligent (land) animal and the animals with the best interface for crafting and using tools.

Though it's possible that other factors, e.g. social dynamics as described by the Marchiavellian Intelligence Hypothesis, also played a role.

Is it evolutionarily plausible that orcas became smarter?

Orcas have culturally transmitted techniques too (e.g. beach hunting, making waves to wash seals off ice shells, faking retreat tactics, using bait to catch birds, ...), but not (as far as we can tell) close to the sophistication of human techniques which were opened up by tool use.

I think it's fair to say that being slightly more intelligent probably resulted in a significantly larger increase in genetic fitness for humans than for orcas.

However, intelligence also has its costs: Most notably, many adaptations which increase intelligence route through the brain consuming more metabolic energy, though there are also other costs like increased childbirth mortality (in humans) or decreased maximum dive durations (in whales).

Orcas have about 50 times the daily caloric intake of humans, so they have a lot more metabolic energy with which they could power a brain that consumes more energy (and can thereby do more computation). Thus, the costs of increasing intelligence is a lot lower in orcas.

So overall it seems like:

Though it's plausible that (very roughly speaking) past the level of intelligence needed to master all the cultural orca techniques (imagine IQ80 or sth) it's not very reproductively beneficial for orcas to be smarter for learning cultural techniques. However, even though I don't think it's the primary driver of human intelligence evolution, it's plausible to me that some social dynamics caused selection pressures for intelligence that caused orcas to become significantly smarter. (I think this is more plausible in orcas than in humans because intelligence is less costly for orcas so there's lower group-level selection pressure against intelligence.)

Overall, from my evolutionary priors (aka if I hadn't observed humans evolving to be smart) it seems roughly similarly likely that orcas develop human-level+ intelligence as that humans do. If one is allowed to consider that elephants aren't smarter than humans, then perhaps a bit higher priors for humans evolving intelligence.[1]

Behavioral evidence

Anectdotes on orca intelligence:

Two more anecdotes showing orcas have high dexterity:

Also, some orca populations hunt whales much bigger than themselves, like calfs of humpback, sperm, or blue whales. Often by separating them from their mother and drowning them.

Evidence from wild orcas

(Leaving aside language complexity, which is discussed below,) I think what we observe from wild orcas, while not legibly as impressive as humans, would still be pretty compatible with orcas being smarter than humans (since it's find sth we don't observe, but what we probably would expect to see if they were as smart as us).

(Orcas do sometimes get stuck in fishing gear, but less so than other cetaceans. Hard to tell whether humans in orca bodies would get stuck more or less.)

(I guess if they were smarter in abstract reasoning than the current smartest humans, maybe I'd expect to see something different, though hard to say what. So I think they are currently not quite super smart, but it's still plausible that they have the potential to be superhumanly smart, and that they are currently only not at all trained in abstract reasoning.)

Evidence from orcas in captivity

I mostly know of a couple of sublte considerations and pieces of evidence here, and don't share them in detail but just give some overview.

I think overall the observations are very weak evidence against orcas being as smart as humans, and nontrivial evidence against them being extremely smart. (E.g. if they were very extremely smart they maybe could've found a way to teach trainers some simple protolanguage for better communicating.)

I'm not sure here, but e.g. it doesn't seem like orcas learn tricks significantly faster than bottlenose dolphins, but maybe the bottleneck is just communication ability for what you want the animals to do. (EDIT: Actually orcas seem to often learn tricks a bit slower than bottlenose dolphins, though orcas are also often a lot less motivated to participate.) Still, I'd sorta have expected something more impressive, so some counterevidence.

Thoughts on orca languages

I have quite some difficulty to relatively quickly estimate the complexity of orca language. I could talk a bunch about subtleties and open questions, but overall it's like "it could be anything from a lot less complex to a significantly more sophisticated than human language". I'd say it's slight evidence against full human-level language complexity. (Feel free to ask for more detail in the comments. Btw, there are features of orca vocalizations which are probably relevant and which are not visible in the spectrogram.)

Very few facts:

Orca language is definitely learned; different populations have different languages and dialects.

It takes about 1.5 years after birth[2] for orca calfs to fully learn the calls of their pod (though it's possible that there's more complexity in the whistles, and also there are more subclusters of calls which are being classified as the same calltype).

Louis Herman's research on teaching bottlenose dolphins language understanding

In the 80s, Louis Herman et al taught bottlenose dolphins to execute actions defined through language instructions. The experiments used proper blinding and the results seem trustworthy. Results include:

AFAIK, this is the most impressive demonstration of grammatical ability in animals to date. (Aka more impressive than great apes in this dimension. (Not sure about parrots though, though I haven't yet heard of convincing grammar demonstrations as opposed to it just being speech repetition.))

In terms of evolutionary distance and superficial brain-impressiveness, orcas are to bottlenose dolphins roughly as humans are to chimps, except that the difference between orcas and bottlenose dolphins is even a big bigger than between humans and chimps, so this is sorta promising.

Neuroscientific considerations

Orca brain facts

(Warning: "facts" is somewhat exaggerated for the number of cortical neurons. Different studies for measuring neural densities sometimes end up having pretty different results even for the same species. But since it was measured through the optical fractionator method, the results hopefully aren't too far off.)

Orcas have about 43 billion cortical neurons - humans have about 21 billion. The orca cortex has 6 times the area of the human cortex, though the neuron density is about 3 times lower.

Interspecies correlations between cortical neurons and behavioral signs of intelligence

(Thanks to LuanAdemi and Davanchama for much help with this part.)

I've tried to estimate the intelligence of a few species based on their behavior and assigned each species a totally subjective intelligence score, and a friend of mine did the same, and I roughly integrated the estimates together to what seems like a reasonable guess. Though of course the intelligence scores are very debateable. Here are the results plotted together with the species' numbers of cortical neurons[3]:

As can be seen, the correlation is pretty strong, especially within mammals (whereas the birds are a bit smarter than I'd estimate from cortical neuron count). (Though if I had included humans they would be an outlier to the top. The difference between humans and bottlenose dolphins seems much bigger than between bottlenose dolphins and chimps, even though the logarithmic difference in cortical neuron count is similar.)

(Also worth noting that average cortical neural firing rates don't need to be the same across species. Higher neuron densities might correlate with quicker firing and thus more actual computation happening. That birds seem to be an intelligent outlier above is some evidence for this, though it could also be that the learning algorithms of a bird's pallium is just a bit more efficient than that of the mammalian cortex or so.)

How much does scale vs other adaptations matter?

A key question is "how much does intelligence depend on scale vs other adaptations?".

Here are some rough abilities that seem useful for intelligence that seem like they might probably come in some way from non-upscaling adaptations (rather than just arising as side-effect of upscaling):

(Some of those might already exist to some extent in non-human land mammals too though.)

It's also conceivable that humans got more adaptations that e.g. increased the efficiency of synapsogenisis or improved the learning algorithms somewhat, though personally I'd not expect that a few million years of strong selection for intelligence in humans were able to produce very significant improvements here.

We should expect humans to have more of those non-scaling intelligence improving mutations: Orcas are much bigger than humans, so the fraction of the metabolic cost the brain consumes is smaller than in humans. Thus it took more selection pressure for humans to evolve having 21billion neurons than for orcas to have 43billion.[1] Thus humans might have other intelligence-increasing mutations that orcas didn't evolve yet.

The question is how important such mutations are in contrast to scaling up? And in so far as they matter, were they hard to evolve or easy to evolve once the brain was large enough to make use of metacognitive abilities?

My uncertain guess is that, within mammalian brains, scaling matters a lot more for individual intelligence, and that most of the subtleties of intelligence (e.g. abstract pattern recognition or the ability to learn language) don't require hard-to-evolve adaptations. (Though better social learning was probably crucial for humans developing advanced cultural techniques. Also, it's not like I think scale alone determines the full cognitive skill profile: I think there are other adaptations that can trade off different cognitive abilities, as possibly unrealistic example e.g. between memory precision and context generalization.)

Overall guess

Having read the above, you might want to try to think for yourself how likely you think it is that orcas are as smart or smarter than humans, before getting contaminated with my guess. (Feel free to post your guess in the comments.)

Orca intelligence is very likely going to be shaped in a somewhat different way than human intelligence. Though to badly quantify my estimates on how smart average orcas might be (in some rough "potential for abstract reasoning and learning" sense):

I'd say 45% that average orcas are >=-2std relative to humans, and 20% that they are >=6std.[4]

Aside: Update on my project

Follow up to: Orca communication project

I'm currently trying to convince a facility with captive orcas to allow me to do my experiment there, but the chances are mediocre. Else I'll try to see whether I can do the experiments with wild orcas, though it might be harder to get much interaction time and it requires getting a permit for doing the experiment with wild orcas, which might also be hard to get.

I'm now no longer searching for collaborators for doing the relevant technical language research work (though still reach out if interested)[5]. However, I'm looking for:

Those 2 roles can be filled by the same person. If you might be interested in filling one or both of those roles, please message me so we can have a chat (and let me know roughly how much money you'd want).

In case you're wondering, no this isn't a hindsight prediction from me having observed orca's large brains. Orcas are the largest animal engaging in collaborative hunting. Sperm whales would also be roughly similarly likely to develop intelligence on my evolutionary priors - they have even more metabolic energy though they are less social than orcas.

Note that orcas have about 17 months gestation period.

For asian elephants we actually don't have measurements, so I took estimated values from wikipedia, though hopefully the estimates aren't too bad since we have measurements for african elephants. Also measurements can be faulty.

Though again, it's about potential for if they got similar education or so. I'd relatively strongly expect very smart humans to win against current orcas in abstract reasoning tests, even if orcas have higher potential.

A smart friend of my tried to do the research but it seems like I'm just unusually good and fast at this research and it didn't seem like I could be sped up significantly, so I'm planning to do the technical research myself and find good ways to delegate the other work to other competent people.