- I was intending to write and post one (hypo)thesis [relating to thinking (with an eye toward alignment)] each day this Advent, starting on 24/12/01 and finishing on 24/12/24.

- Ok, so that didn't happen, and it is now 25/03/17, but whatever — an advent of thought can happen whenever :). I'll be posting the first 8 notes today. (But much of the writing was done in Dec 1–24.)

- Most of these notes deal with questions that would really deserve to have very much more said about them — the brief treatments I give these questions here won't be doing them any justice. I hope to think and write more about many of the topics here in the future.[1]

- I've tried to state strong claims. I do (inside view?) believe each individual claim (at maybe typically [2]), but I certainly feel uneasy about many claims (feel free to imagine a version of the notes with even more "probably"s and "plausibly"s if you'd prefer that style) — I feel like I haven't thought about many of the questions adequately, and I'm surely missing many important considerations.[3] I'm certainly worried I'm wrong about it all![4][5]

- Even if you happen to find my theses/arguments/analysis wrong/lacking/confused, I'm hopeful you might find [the hypotheses]/[the questions my notes are trying to make progress on] interesting.

- If you reason me out of some claim in this list, I'd find that valuable![6]

- While many notes can stand alone, there are some dependencies, so I'd recommend reading the notes in the given order. The (hypo)theses present a somewhat unified view, there are occasional overlaps in their contents, and there are positive correlations between their truth values. A table of contents:

- notes 1–8: on thought, (its) history (past and future), and alignment, with an aim to make us relate more appropriately to "understanding thinking" and "solving alignment"[7]

- thinking can only be infinitesimally understood

- infinitude spreads

- math, thinking, and technology are equi-infinite

- general intelligence is not that definite

- confusion isn't going away

- thinking (ever better) will continue

- alignment is infinite

- making an AI which is broadly smarter than humanity would be most significant

- notes 9–18: on values/valuing, their/its history (past and future), and their/its relation to understanding, with an aim to help us think better about our own values and the values present/dominant in the world if we create an artifact distinct and separate from humanity which is smarter than humanity (not published yet)

- notes 19–24: on worthwhile futures just having humanity grow more intelligent and skillful indefinitely (as opposed to ever creating an artifact distinct and separate from us which outgrows us[8]), with an aim to get us to set our minds tentatively to doing just that (not published yet)

- notes 1–8: on thought, (its) history (past and future), and alignment, with an aim to make us relate more appropriately to "understanding thinking" and "solving alignment"[7]

Acknowledgments. I have benefited from and made use of the following people's unpublished and/or published ideas on these topics: especially Sam Eisenstat; second-most-importantly Tsvi Benson-Tilsen; also: Clem von Stengel, Jake Mendel, Kirke Joamets, Jessica Taylor, Dmitry Vaintrob, Simon Skade, Rio Popper, Lucius Bushnaq, Mariven, Hoagy Cunningham, Hugo Eberhard, Peli Grietzer, Rudolf Laine, Samuel Buteau, Jeremy Gillen, Kaur Aare Saar, Nate Soares, Eliezer Yudkowsky, Hasok Chang, Ian Hacking, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Martin Heidegger and Hubert Dreyfus, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and Gregory B. Sadler, various other canonical philosophers, and surely various others I'm currently forgetting.[9]

1 thinking can only be infinitesimally understood[10]

- The following questions about thinking are sometimes conceived of as ones to which satisfactory answers could be provided (in finite time)[11]:

- "What's intelligence?"

- (a probably better version of the above:) "How does thinking work?"

- (a probably still better version of the above:) "How should one think?"

- I think it is a mistake to think of these as finite problems[12] — they are infinite.

- We can define a "complexity class" of those endeavors which are infinite; I claim the following are some central endeavors in this class: figuring out math, understanding intelligence, and inventing all useful technologies.[13]

- Why are these three endeavors infinite? The next two notes will (among other things) provide an argument that if one of these endeavors is infinite, then so are the other two. And I will assert without providing much justification (here) that math is infinite.

- What do I mean by an infinite endeavor? I could just say "an endeavor such that any progress that could be made (in finite time) [won't be remotely satisfactory]/[won't come remotely close to resolving the matter]". I'd maybe rather say that an infinite endeavor is one for which after any (finite) amount of progress, the amount of progress that could still be made is greater than the amount of progress that has been made, or maybe more precisely that at any point, the quantity of “genuine novelty/challenge” which remains to be met is greater than the quantity met already.

- Hmm, but consider the endeavor of pressing a button very many times in some setup which forces you into mindlessness about how you are to go about getting the button pressed very many times — maybe you wake up each morning in a locked room with only a button in it, getting rewarded one util (whatever that means) for each day on which you press the button, maybe with various other constraints that make it impossible for you to make an art out of it or take any kind of rich interest in it beyond your interest in goodness-points or really think about it much at all — basically, I want to preclude scenarios which look like doing a bunch of philosophy about what it is for something to be "that button" and what it is for that button to "be pressed" and what "a day" is and developing tech/science/math/philosophy around reliably getting the button pressed and so on. Are we supposed to say that pressing the button many times is an infinite endeavor for you, because there is always more left to do than has been done already?

- I want to say that pressing the button many times (given the setup above) is not an infinite endeavor for you — I want to say that largely because that conflicts with my intuitive notion of an infinite endeavor and because it makes at least one thing I'd like to say later false. I might be able to get away with saying it is not infinite because it only presents a small amount of genuine novelty/challenge, saying that we should go with the last definition in the superitem (i.e., the parent item to this item on this list), but I'm sort of unhappy with the state of things here.

- This button example makes me consider changing the definition of an infinite endeavor to be the following: an infinite endeavor is one which cannot be finitely well-solved/finished on any meta-level — i.e., it itself cannot be remotely-well-[solved/finished], and figuring out how to go about working on it cannot be remotely-well-[solved/finished], and figuring out how to go about that cannot be remotely-well-[solved/finished] either, and so on.

- Actually, it should be fine to just require that the meta-[problem/endeavor] cannot be remotely-well-[solved/finished] — i.e., that there is no -satisfactory finite protocol for the object-[problem/endeavor], because I think this would imply that the object-endeavor itself cannot be remotely-well-finished (else we could have a finite protocol for it: just provide the decent finite solution) and that the higher meta-endeavors cannot be remotely-well-finished either (because finitely remotely-well-finishing a higher meta-endeavor would in particular provide a finite protocol for the object-endeavor).

- We could speak instead of "practically infinite endeavors" — endeavors for which for any amount of progress one could ever make on the endeavor in this universe, the importance-weighted-quantity of "stuff" which is not yet figured out will be greater than the importance-weighted-quantity of "stuff" which has been figured out. That an endeavor is practically infinite is [a weaker assertion than that it is infinite], and we could retreat to those assertions throughout these notes — such claims would be sufficient to support our later assertions. Actually, we could probably even retreat to the weaker assertions still that certain endeavors couldn’t be remotely finished in (say) 1000 years of humans doing research. But going with the riskier claim seems neater.

- If you conceive of making progress on an endeavor as collecting pieces with certain masses in and only being able to collect finitely many pieces in any amount of time, then you should imagine the sum of the masses of all pieces being infinite for an infinite endeavor.

- With this picture in mind, one can see that whether an endeavor is infinite depends on one's measure — and e.g. if all you're interested in in mathematics is finding a proof of some particular single theorem, then maybe "math" seems finite to you. For these notes, I want to get away with just saying we're measuring progress in some intuitive way which is like what mathematicians are doing when saying math is infinite, marking the question of how to think of this measure as an important matter to resolve later. For example, maybe it would be natural to make the measure time-dependent (that is, changing with one’s current understanding), since it might be natural for what is potentially important (as progress? or for making progress?) to depend on where one is?

- I should clarify that there is a different conception of an infinite endeavor as one in which there is an infinite amount to do in a much weaker sense, such that there is some sort of convergence toward having finished the endeavor anyway. In this picture where one is collecting pieces, this is like there being infinitely many pieces, but with the sum of all their masses being finite, so even though one can only collect finitely many pieces by any finite time, one can see oneself as getting arbitrarily close to having solved the problem. And I want to clarify that this is not what I mean when I say an endeavor is infinite — I mean that it is much more infinite than this!

- Generally, given some reasonable and/or simplifying assumptions, it should be equivalent to say that an infinite endeavor is one in which there is an infinite amount of cool stuff to be understood (whereas (by any finite time) one could only ever understand a finite amount). Given some assumptions, it should also be equivalent to say that an infinite endeavor is one which presents infinitely many challenges of at least some constant significance/importance (in the above picture with pieces, one should be allowed to merge pieces into one challenge to have that equivalence work out).

- An infinite endeavor can only be infinitesimally completed/solved.

- If we were to make the measure time-dependent, I’d maybe instead want to say “an infinite endeavor can only be (let’s say) -completed/solved”, and maybe instead call it a forever-elusive/slippery/escaping question/quest/problem/endeavor. Maybe I should be more carefully distinguishing quests/questions/problems from corresponding pursuits/endeavors-to-address/solutions — I could then speak here of, say, it being an infinite endeavor to handle/address an elusive question. Anyway, a problem continuing to slip away in this sense wouldn’t imply that it is at each time only infinitesimally solved according to the measure appropriate to that same time, though it would of course still imply that the problem will always seem mostly unsolved, and it would (given some fairly reasonable assumptions) also imply that for each state of understanding, there is another (more advanced) state of understanding from the vantage point of which the fraction of progress which had been made by the earlier state is arbitrarily close to .

- Math is infinite.

- I should say more about what I mean by this. For math in particular, I want to claim that always, the total worth/significance/appeal of theorems not yet proven will be greater than the total worth/significance/appeal of theorems already proven, the total worth/significance/appeal of objects not yet discovered/identified/specified/invented will be greater than the total worth/significance/appeal of objects not yet discovered/identified/specified/invented, and analogously for proof ideas and for broad organization (and maybe also some other things).

- Like, I think that when one looks at math now, one gets a sense that there's so much more left to be understood than has been understood already, and not in some naive sense of there having been only finitely many propositions proved of the infinitely many provable propositions, but in a much more interesting significance-weighted sense; my claim is that it will be like this forever.[14]

- an objection: "Hmm, but isn't there a finite satisfactory protocol for doing math, because something like the present state of this universe could plausibly be finitely specified and it will plausibly go on to "do math" when time-evolved satisfactorily? (And one could make something with a much smaller specification that still does as well, also.) We could plausibly even construct a Turing machine "doing roughly at least as much math" from it? So isn't math finite according to at least one of the earlier definitions?"

- my response: If it does in fact get very far in math (which is plausible), it would be a forever-self-[reprogramming/reinventing] thing, a thing indefinitely inventing/discovering and employing/incorporating new understanding and new ways of thinking on roughly all levels. I wouldn't consider it a fixed protocol (though I admit that this notion could use being made more precise).[15]

- It would be good to more properly justify math being infinite (which could benefit from the statement being made more precise (which would be good to do anyway)); while Note 2 and Note 3 will provide some more justification (and elaboration), I’m far from content with the justification for this claim provided in the present notes.

- "How should one think?" is as infinite as mathematics (I'll provide some justification for this in the next few notes), so the endeavor to understand thinking will only ever be infinitesimally finished. Much like there's no "grand theorem/formula of mathematics" and there's no "ultimate technology (or constellation of technologies)", there's no such thing as a (finite) definitive understanding of thinking — understanding how thinking works is not a problem to be solved.

- "How does thinking work?" should sound to us a lot like "how does [the world]/everything work?" (asked in the all-encompassing sense[16]) or "how does doing stuff work?". I hope to impart this vibe further and to make the sense in which these should sound alike more precise with the next three notes.

- All that said, this is very much not to say that it is crazy to work on understanding thinking. It's perfectly sensible and important to try to understand more about thinking, just like it's perfectly sensible and important to do math. Generally, we can draw a bunch of analogies between the character of progress in math and the character of progress in understanding thinking.

- In both math and investigating thinking, progress on an infinite thing can still be perfectly substantive.[17] A mathematical work can be perfectly substantive despite being an infinitesimal fraction of all of math.

- It can still totally make sense to try to study problems about intelligence which relate to many aspects of it, much like it can make sense to do that in math.

- It can still totally make sense to prefer one research project on thinking to another — even though each is an infinitesimal fraction of the whole thing, one can still easily be much greater than the other.

- However, working on finding and understanding the structure of intelligence in some definitive sense is like working on finding "the grand theorem of math" or something.

- I'm very much not advocating for quietude on an endeavor in response to its infinitude. I think there are many infinite endeavors which merit great effort, and understanding thinking is one of them. In fact, understanding thinking is probably a central quest for humanity and pretty much all minds (that can get very far)!

- One could object to my claim that "I will understand intelligence, the definite thing" is sorta nonsense by saying "look, I'm not trying to understand thinking-the-infinite-thing; I'm trying to understand thinking as it already exists in humans/humanity/any-mind-that's-sorta-smart, which is surely a finite thing, and so we can hope to pretty completely understand it?". I think this is pretty confused. I will discuss these themes in Note 4.

- And again, I think it is perfectly sensible and good to study intelligence-the-thing-that-already-exists-in-humans (for example, as has already been done by philosophers, logicians, AI researchers, alignment researchers, mathematicians, economists, etc.); I just think it is silly to be trying to find some grand definitive formula for it (though again, it totally makes sense to try to say broad things that touch many aspects of intelligence-the-thing-that-already-exists-in-humans, just like it makes sense to try to do something analogous in math).

2 infinitude spreads

- An endeavor being infinite often causes other related endeavors to be infinite. In particular:

- If is an infinite endeavor, then "how should one do ?" is also infinite.[18] For example: math is infinite, so "how should one do math?" is infinite; ethics is infinite, so "how should one do ethics?" is infinite.[19]

- If is an infinite endeavor and there is a "faithful reduction" of to another endeavor , then is also infinite. (In particular, if an infinite endeavor is "faithfully" a subset of another endeavor , then is also infinite.)[20] For example, math being infinite implies that stuff in general is infinite; "how should one do math?" being infinite implies that "how should one think?" is infinite.

- If an endeavor constitutes a decently big part of an infinite endeavor, then it is infinite.[21][22] For example, to the extent that language is and will remain to be highly load-bearing in thinking, [figuring out how thinking should work] being infinite implies that [figuring out how language should work] is also infinite.

- Thinking being infinite can help make some sense of many other philosophical problems/endeavors being infinite.[23]

- Specifically:

- If "solving" a philosophical problem would entail understanding some aspect of thinking which has a claim to indefinitely constituting a decently big part of thinking, then

- If "solving" a philosophical problem would entail making a decision on [how one's thinking operates in some major aspect], that philosophical problem is not going to be remotely "solved", because one will probably want to majorly change how one's thinking works in that major aspect later.

- Here are some problems whose infinitude could be explained by the infinitude of thinking in this way (but whose infinitude could also be explained in other ways):

- "how does learning work?"

- “how does language work?”

- "how should one assign probabilities?"

- “what are concepts? which criteria determine whether concepts are good?”

- "how does science work?"

- "how should one do mathematics?"

- "what is the character of value(ing)?"

- You might feel indifferent about some of these problems; you could well have a philosophical system in which some of these are not load-bearing (as I do). My claim is that those problems which are genuinely load-bearing in your philosophical system are probably infinite, and their infinitude can be significantly explained by the infinitude of "how should one think?".

- We could imagine a version of these problems which could be solved — for example, one might construct a GOFAI system which has a (kinda-)language+meaning which is plausibly load-bearing for it but which will not be reworked. My claim is that for a mind which will indefinitely be thinking better, if it has "language" and "meaning", to the extent these are load-bearingly sticking around indefinitely, the mind will also "want to" majorly rework them indefinitely.

- Again, all this is very much not to say that one cannot make progress on these philosophical problems — even though any progress will be infinitesimal for these infinite endeavors, one can make substantive progress on them (just like one can make substantive progress in math), and I think humanity is in fact continuously making substantive progress on them. So, for many philosophical problems/endeavors , I can get behind “we’re pretty much no closer to solving now than we were 2000 years ago” — meaning that only an infinitesimal fraction has been solved, just like earlier, or that only a finite amount has been figured out, with a real infinity still remaining, just like earlier — while very much disagreeing with the possible followup “that is, we haven’t made any progress on since 2000 years ago” — I think probably more than half of the philosophical progress up until now happened since 1700, and maybe even just since 1875.[24]

- Specifically:

- Saying these problems are infinite because of the infinitude of "how should one think?" can make it seem like we are viewing ourselves very much "from the outside" when tackling these problems and when tackling "how should one think?", but I also mean to include tackling these problems more "from the inside".

- What do I mean by tackling these problems "from the outside" vs "from the inside"? Like, on the extreme of tackling a problem "from the outside", you could maybe imagine examining (yourself as) another thinking-system out there, having its language and beliefs and various thought-structures somehow made intelligible to you, with you trying to figure out what eg its concept of "existence" should be reworked to. Tackling "the same problem" from the inside could look like having various intuitions about existence and trying to find a way to specify what it means for something to exist in terms of other vocabulary such that these intuitions are met (this can feel like taking "existence" to already be some thing, just without you having a clear sense of what it is). And a sorta intermediate example: asking yourself why you want a notion of "existence", trying to answer that by examining cases where your actions (or thinking more broadly) would depend on that notion, and seeking to first make sense of how to operate in those cases in some way that routes through existence less. Of course, in practice, we always have/do an amalgam of the inside and outside thing.[25]

- I'm saying that the infinitude of [such investigations which are more from the inside of a conceptual schema] could also be partly explained by the infinitude of "how should thinking work?".[26]

- Wanting to rework one's system of thought indefinitely is also a reason for keeping constituent structures provisional.

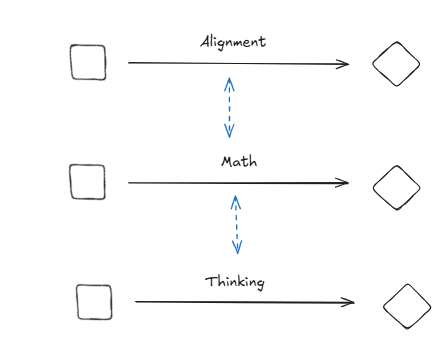

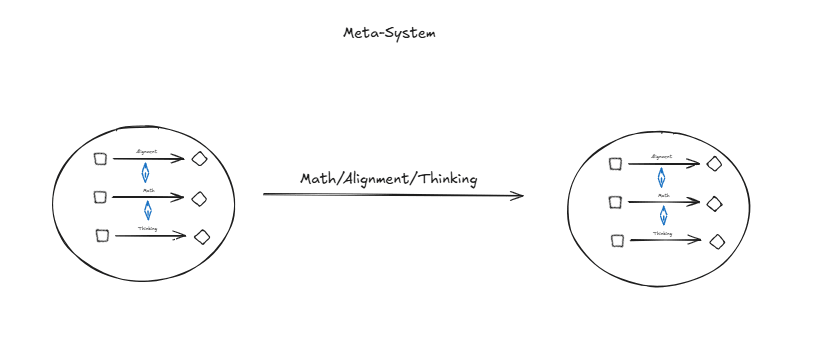

3 math, thinking, and technology are equi-infinite

- If one of math, understanding intelligence, and inventing useful technologies is infinite, then so are the other two. (An argument for this is given in items 2–6 of this list.)

- So, if you think any one of the three is infinite, then you should also think that the other two are. In particular, if you're on board with my earlier assertion that math is infinite, then you should also agree that thinking and technology are infinite. Or you could prima facie buy into technology being infinite, and get to thinking that thinking and math are infinite from there.

- If math is infinite, then "how should one do math?" is infinite. 2. I could just appeal to note 2 item 1.1 to justify this, but it makes sense to also justify this independently (especially given that I haven't justified 2.1.1 well). (Also, if we went with the definition of an infinite endeavor in 1.4.3(.1), then we'd be done by definition here, but that's not too exciting, either.) 3. I guess I'd first like to try to get you to recognize that if you accepted my earlier assertion that math is infinite, then you might have already sorta accepted that doing math is infinite, at least in the following sense: 1. If we think of math-the-more-object-level-endeavor as being ultimately about printing proofs of propositions, then we should plausibly already think of say, mathematical ideas (e.g., the idea of a probabilistic construction) or mathematical objects/constructions (e.g., a vector space) or frames/arenas organizing mathematical fields (e.g., the scheme-theoretic organization of algebraic geometry) as meta-level things — they are like tools one uses to print proofs better. 2. This isn't to say that math is in fact ultimately well-thought-of as not also being about defining objects and coming up with new ideas and so on. But I want to get across the sense that these live in significant part also on the meta-level — that they are not just things in the object-domain, but also components of us doing math. Getting further in math centrally involves gaining these tools, from others or by making them yourself.[27] 4. Quite generally, given that understanding a domain better blends together with thinking better in the domain to a significant extent, if you think there's an infinitely rich variety of things to understand in mathematics, this gives you some reason to think that there is also an infinitely rich variety of structure to employ in doing mathematics, so it gives you some reason to think that figuring out how one should do math is an infinite endeavor.

- If "how should one do math?" is infinite, then "how should one think?" is also infinite.

- We could just say this is a special case of 2.1.2 (i.e., item 1.2 from Note 2), but it also makes sense to justify this separately/again. I think it'd be super bizarre for mathematical thinking and thinking in general not to be equi-infinite; it'd be particularly bizarre for getting better at thinking to be infinitely "easier" than getting better at mathematical thinking. They are just way too similar (in the relevant aspect(s)). It's not like math researchers use thinking in some profoundly different class when doing math (compared to when doing other thinking). Things in general are way too much like math way too much of the time. Doing things in general involves doing math way too centrally.

- If "how should one think?" is infinite, then tech is also infinite.

- The question "how should one think?" is/[centrally involves] the question "which thinking-[structures/technologies] should one make/use?", so this latter question is then also infinite (maybe by 2.1.3). And "thinking-technologies" are ("faithfully") a subset of all technologies, so tech is also infinite by 2.1.2.[28]

- Finally, if tech is infinite, then math is infinite.

- The vibes are very similar, in the relevant way.

- In particular, technological objects are a lot like mathematical objects. From this, one might think that tech is like a fragment of math, in which case one might think that math could only be more infinite than tech, appealing to 2.1.2.

- But also, our mathematical ideas "show up load-bearingly" all over the place in our technologies, so one could try to see math as a fragment of tech and to infer its infinitude from the infinitude of tech using 2.1.3.

- Actually, our math just is one kind of tech we're building (for our thinking and also for other doings) — this gives another way to see math as a subendeavor of tech for us, and one can then again try to infer its infinitude using 2.1.3.

- Additionally, math shows up load-bearingly in developing tech, so one could infer the infinitude of developing tech from the infinitude of tech using 2.1.1 and then infer the infinitude of math from that using 2.1.3.

- Let us say more about math and tech having similar vibes (in the relevant way). One could tell many stories to communicate that the vibes are similar; here are the premises of a few:

- Mathematical objects are often invented/discovered to do things, to [participate in]/support/[make possible] our (mathematical) activities, and to help us with problems/projects — just like (other) technological objects.

- One can think of a technology in terms of its construction/composition/design/[internal structure], like an engineer might, or one can think of a technology in terms of [its function(s)]/[its purpose(s)]/[what one can do with it]/[how to use it]/[what it is like as it operates]/[its properties]/[how it relates to other things]/[the surrounding external structure][29], like one usually does when thinking about doing stuff with the technology. This is also true of mathematical devices — for example, one can think of the real numbers in terms of their construction (e.g. as Cauchy sequences of rationals[30] or Dedekind cuts of rationals), or one can instead think of the real numbers as a complete ordered field, or as being involved in geometry and analysis in various ways, etc.; one can think of the homology groups of a topological space in terms of their construction (e.g. via the simplicial route or the singular route), or one can instead think of homology groups as things of which the various theorems in Hatcher involving homologies are true (indeed, one can pin down the homology of a space uniquely as the thing satisfying some axioms — see Section 2.3 and Theorem 4.59 in Hatcher[31]); one can think of a product of topological spaces as having tuples as points and having its topology generated by cylinder sets, or as a canonical topological space equipped with continuous maps to the original spaces.

- One can also just be using a technology without thinking about it much (for example, you can be using your laptop to write notes without thinking about your laptop much), and one can also be using a mathematical thing in one's thinking without thinking about it much (for example, you can be doing stuff with real numbers without explicitly thinking about how their construction or even their properties). (However, a difference: there is structure supporting/[involved in] your use of your laptop which lives outside your head, whereas the structure involved in your use of a vector space lives entirely in your head.)

- Note that the implications about infinitude in items 2-5 on this list form a loop, so we've provided an argument that these endeavors are equi-infinite. More precisely, we've given an argument that if any one of these problems/endeavors is infinite, then any other is also infinite; this means that they are either all finite or all infinite.[32]

- You might say: “Okay, I agree that there’s a genuine infinity of mathematical objects (and so on), a genuine infinity of technologies, and a genuine infinity of thinking-technologies in particular. But couldn’t there be a level above all these infinite messes where there’s some simple thing?”. My short answer is: no, e.g. our handling of mathematical objects is technological/organic throughout. A longer answer:

- For example, let's look at making concepts.[33] Making concepts looks e.g. like having a varied system for morphological derivation and inflection, giv-ing parti-cul-ar ab(i)-(bi)li(s)-ti-es to pro-duce con-cep-t-s. Here are some more example high-level ways in which new concepts can be found:

- become familiar with many toy cases; push yourself to see them as clearly as possible; if any objects show up, try to see if they can also be used in other contexts;

- when you have a toy setting worked out, ask what "auxiliary constructions"/"nontrivial ideas" were involved[34];

- generalize existing things; unify existing things; articulate similarities; find what's responsible for similarities;

- make existing looser notions more precise; make distinctions;

- get concepts for a novel context via analogy to some familiar context;

- look for a thing which would "work" a certain way; look for a thing which would play a certain role[35];

- more generally, have some constraints on a hypothetical thing in mind and look for a concrete thing which would satisfy those constraints;

- in particular, for various particular relations or functions, look for what stands in that relation with some thing or what that function takes some thing to;

- in particular, look for the (logical) cause of some property or event;

- look for ways you can relate something to other things; look for things you can do with it; look for ways to transform it;

- enumerate all things of some kind and see if any are useful.

- Making concepts can look a lot like making (more explicit) technologies, in which surely very much of our thinking is importantly involved.

- Also, I'd sorta object to thinking there is a level "above" this messy world of concepts. There are surely structures present in us-doing-math beyond easily visible mathematical concepts, including structures of different kinds, but instead of thinking of these structures as handling and organizing concepts from above, I think it's better to think of the whole thinking-shebang as like an organic thing, so this sounds e.g. like thinking that [blood circulation]/[the cardiovascular system] is a structure "above" the organs, or like saying a tree is a structure organizing koalas. Additionally, the structure surrounding a concept is in significant part [given by]/[made of] other concepts.

- You might say: "hmm, you're talking about all these things we can easily see, but couldn't there be a nice hidden structure which handles things? like, a structure in the brain?".

- Well, I certainly have been talking about those things we can see better, and there are surely many structures in our thinking-activities[36] that we can't see that clearly at present. It seems unlikely that there'd be these central hidden things of a fundamentally different character than the various technological things we can see, though.

- You might say: "hmm, maybe thinking is this organic-technological mess now, but couldn't it become well-organized? couldn't there be some sort of formula for thinking which remains to be discovered/reified?". Or maybe you might say: "hmm, maybe thinking is an organic-technological mess, but couldn't it really be a shadow of a very nice thing?"

- There are surely nice things shadowed in thinking. For example, (almost all) clear human mathematical statements and clear mathematical proofs (especially from after like 1950 or whatever) have formal counterparts in ZFC — there's a very real "near-isomorphism" of an important thing in human mathematical (thinking-)activities with a nice formal thing. For another example, there are ways to see bayesianism (usually combined with other interesting "ideas") in various things from (frequentist) statistical methods to plant behavior[37]. It can often be helpful to understand something about the actual thing by evoking the nice thing; it is in some contexts appropriate to think almost entirely about a nice thing to figure out something about the actual thing. But I think there are very many nice things shadowed in thinking, with developing thinking continuing to shadow more cool things on all levels indefinitely.

- This seems close to asking whether the (technological) world would eventually just "have" one kind of thing. And it seems unlikely that it would!

- There will probably continue to be a very rich variety of (thinking-)structures in use.

- If I had to guess at some single higher "structure" centrally "behind/in" thinking, I'd say "one is creative; one finds/invents and finds uses for (thinking-)structures".[38] But I don't think this is some sort of definite/simple thing — I think this will again be rich, involving many "ideas".

- I've tried to say more in response to these questions in the next few notes.

- For example, let's look at making concepts.[33] Making concepts looks e.g. like having a varied system for morphological derivation and inflection, giv-ing parti-cul-ar ab(i)-(bi)li(s)-ti-es to pro-duce con-cep-t-s. Here are some more example high-level ways in which new concepts can be found:

4 general intelligence is not that definite

- In note 1, I claimed that "I will get some remotely definitive understanding of problem-solving" is sorta nonsense like "I will solve/[find a grand theor[y/em] for] math" or "I will conceive of the ultimate technology". One could object to this by saying "look, I'm not trying to understand intelligence-the-infinite-thing; I'm trying to understand intelligence as it already exists in humans/humanity/any-one-particular-mind-that's-sorta-generally-intelligent, which is surely a finite thing, and so we can hope to pretty completely understand it?". I think this is still confused; here's my response:

- Intelligence in humans/humanity/any-reasonable-mind-that's-sorta-smart will already be a very rich thing. Humans+humanity+evolution has already done very much searching for structures of thinking, and already found and put to use a great variety of important ones.

- [Humans are]/[humanity is] self-reprogramming. (Human self-reprogramming needn't involve surgery or whatever.) A central example: [humans think]/[humanity thinks] in language(s), and humans/humanity made language(s) — in particular, we made each word in (each) language.[39] Humanity is amassing an arsenal of mathematical concepts and theorems and methods and tricks. We make tools[40], some of which are clearly [parts of]/[used in]/[playing a role in] thinking, and all of which[41] have been involved in us doing very much in the world. We learn how to think about various things and in various ways; when doing research, one thinks about how to think about something better all the time. I'm writing these notes in large part to restructure my thinking (and hopefully that of some others) around thinking and alignment[42] (as opposed to like, idk, just stating my yes/no answers to some previously well-specified questions (though doing this sort of thing could also totally be a part of improving thinking)).

- Anyway, yes, it's probably reasonable to say that humanity-now has some finite (but probably "big") specification. (Moreover, I'm pretty sure that there is a 1000-line python program such that running that program on a 2024 laptop with internet access would start a "process" which would fairly quickly take over the world and lead to some sort of technologically advanced future (like, with most of the compute used being on the laptop until pretty late in the part of the process until takeover).) Unfortunately, understanding a thing is generally much harder than specifying it. Like, consider the humble cube[43]. Is it obvious to you that its symmetry group (including rotations only, i.e., only things you can actually do with a solid physical cube) is , the permutation group on elements?[44] Or compare knowing the weights of a neural net to understanding it.

- The gap between specifying a thing and understanding it is especially big when the thing is indefinitely growing, indefinitely self-[reworking/reprogramming/improving] (as [humans are]/[humanity is]).

- Obviously, the size of the gap between the ability to specify a thing and understanding it depends on what we want from that understanding — on what we want to do with it. If all we wanted from this "understanding" was to, say, be able to print a specification of the thing, then there would not be any gap between "understanding" the thing and having a specification of it. Unfortunately, when we speak of understanding intelligence, especially in the context of alignment, we usually want to understand it in its long-term unfolding,[45] then there's a massive gap — for an example, consider the gap between having the positions and momenta of atoms when evolution got started in front of you[46] vs knowing what "evolution will be up to" in billions of years.

- And even in this cursed reference class of comprehending growing/structure-gaining things in their indefinite unfolding, comprehending a thinking thing in its unfolding has a good claim to being particularly cursed still, because thinking things have a tendency to be doing their best to "run off to infinity" — they are actively (though not always so explicitly) looking for new better ways to think and new thinking-structures to incorporate.

- Intelligence in humans/humanity/any-reasonable-mind-that's-sorta-smart will already be a very rich thing. Humans+humanity+evolution has already done very much searching for structures of thinking, and already found and put to use a great variety of important ones.

- Relatedly: one could try to conceive of the ability to solve problems in general as some sort of binary-ish property that a system might have or might not have, and I think this is confused as well.

- I think it makes much more sense to talk loosely about a scale of intelligence/understanding/capability-to-understand/capability/skill, at least compared to talking of a binary-ish property of general problem-solving. While this also has limitations, I'll accept it for now when criticizing viewing general intelligence as a binary-ish thing. (I'm also going to accept something like the scalar view more broadly for these notes, actually.[47])

- Given such a scale of intelligence, we could talk of whether a system has reached some threshold in intelligence, or some threshold in its pace of gaining intelligence. We could maybe talk of whether a system has developed some certain amount of technology (for thinking), or whether its ability to develop technology has reached a certain level.

- We could talk of whether it has put to use in/for its doing/thinking/fooming[48] some certain types of structures.

- But it seems hard to make a principled choice of threshold or of structures to require. Like, there's an ongoing big foom which keeps finding/discovering/inventing/gaining new (thinking-)structures (and isn't anywhere close to being done — the history of thought is only just getting started[49]). Where (presumably before humanity-now) would be a roughly principled place to draw a line?

- One could again try to go meta when drawing a line here, saying it's this capacity to incorporate novel structures itself which makes for an intelligent thing. But this will itself again be a rich developing thing, not a definite thing. In fact, it is not even a different thing from [the thought dealing (supposedly) with object-level matters] for which we just struggled to draw a line above. It's not like we think in one way "usually", and in some completely different way when making new mathematical concepts or inventing new technologies, say — the thinking involved in each is quite similar. (Really, our ordinary thought involves a great deal of "looking at itself"/reflection anyway — for instance, think of a mathematician who is looking at a failed proof attempt (which is sorta a reified line of thought) to try to fix it, or think of someone trying to find a clearer way to express some idea, or think of someone looking for tensions in their understanding of something, or think of someone critiquing a view.)

- One (imo) unfortunate line of thinking which gets to thinking of general intelligence as some definite thing starts from noticing that there are nice uncomputable things like kolmogorov complexities, solomonoff induction (or some other kind of ideal bayesianism), and AIXI (or some other kind of ideal expected utility maximization), and then thinks it makes sense to talk of "computable approximations" of these as some definite things, perhaps imagining some actual mind already possessing/being a “computable approximation” of such an uncomputable thing.

- I think this is like thinking some theorem is "an approximate grand formula for math".

- It is also like thinking that a human mathematician proving theorems is doing some “computable approximation” of searching through all proofs. A human mathematician is really “made of” many structures/[structural ideas].

- More generally, the actual mind will have a lot of structure which is not remotely well-described by saying it's a computable approximation of an infinite thing. (But also, I don’t mean to say that it is universally inappropriate to draw any analogy between any actual thing and any of these infinitary things — there are surely contexts in which such an analogy is appropriate.)

- For another example of this, an "approximate universal prediction algorithm" being used to predict weather data could look like humans emerging from evolution and doing philosophy and physics and inventing computers and doing programming and machine learning, in large part by virtue of thinking and talking to each other in language which is itself made of very many hard-won discoveries/inventions (e.g., there are some associated to each word), eventually making good weather simulations or whatever — there's very much going on here.

- Thinking of some practical string compression algorithm as a computable approximation to kolmogorov compression is another example in the broader cluster. Your practical string compression algorithm will be "using some finite collection of ideas" for compressing strings, which is an infinitesimal fraction of "the infinitely many ideas which are used for kolmogorov compression".

- One more (imo) mistake in this vicinity: that one could have a system impressively doing math/science/tech/philosophy which has some fixed “structure”, with only “content” being filled in, such that one is able to understand how it works pretty well by knowing/understanding this fixed structure. Here's one example of a system kinda "doing" math which has a given structure and only has "content" being "learned": you have a formal language, some given axioms, and some simple-to-specify and simple-to-understand algorithm for assigning truth values[50] to more sentences by making deductions starting from the given axioms[51]. Here's a second example of a system with a fixed structure, with only content being filled in: you have a "pre-determined world modeling apparatus" which is to populate a "world model" with entities (maybe having mechanisms for positing both types of things and also particular things) or whatever, maybe with some bayesianism involved. Could some such thing do impressive work while being understandable?

- I think that at least to a very good approximation, there are only the following two possibilities here: either (a) the system will not be getting anywhere (unless given much more compute than could fit in our galaxy) — like, if it is supposed to be a system doing math, it will not actually produce a proof of any interesting open problem or basically any theorem from any human math textbook (without us pretty much giving it the proof) — or (b) you don't actually understand the working of the system, maybe wrongly thinking you do because of confusing understanding the low-level structure of the system with understanding how it works in a fuller sense. Consider (again) the difference between knowing the initial state and transition laws of a universe and understanding the life that arises in it (supposing that life indeed arises in it), or the difference between knowing the architecture of a computer + the code of an AI-making algorithm run on it and understanding the AI that emerges. It is surely possible for something that does impressive things in math to arise on an understood substrate; my claim is that if this happens, you won't be understanding this thing doing impressive math (despite understanding its substrate).

- Let us focus on systems doing math, because (in this context), it is easier to think about systems doing math than about systems doing science/tech/philosophy, and because if my claim is true for math, it'd be profoundly weird for it to be false for any of these other fields.[52] So, could there be such a well-understood system doing math?

- There is the following fundamental issue: to get very far (in a reasonable amount of time/compute), the system will need to effectively be finding/discovering/inventing better ways to think, but if it does that, us understanding the given base structure does not get us anywhere close to understanding the system with all its built structure. The system will only do impressive things (reasonably quickly) if it can make use of radical novelty, if it can think in genuinely new ways, if it can essentially thoroughly reorganize any aspect of its thinking. If you genuinely manage to force a system to only think using/with certain "ideas/structures", it will be crippled.

- A response: "sure, the system will have to come up with, like, radically new mathematical objects, but maybe the system could keep thinking about the objects the same way forever?". My response to this response: there will probably need to be many kinds of structure-finding; rich structure will need participate in these radically new good mathematical objects being found; you will want to think in terms of the objects, not merely about them (well, to really think remotely well about them, you will need to think in terms of them, anyway)[53]; to the extent that you can make a system that supposedly "only invents new objects" work, it will already be open to thinking radically differently just using this one route you gave it for thinking differently; like, any thing of this kind that stands a chance will be largely "made of" the "objects" it is inventing and so not understandable solely by knowing a specification of some fixed base apparatus[54].[55] I guess a core intuition/(hypo)thesis here is that it’d be profoundly “unnatural”/“bizarre” for thinking not to be a rich, developing, technological sort of thing, just like doing more broadly. Like, there are many technologies which make up a technological system that can support various doings, and there are similarly many thinking-technologies which make up a thinking-technological system which is good for various thinkings; furthermore, the development of (thinking-)technologies is itself again a rich technological thing — really, it should be the same (kind of) thing as the system for supposedly object-level thought.

- In particular, if you try to identify science-relevant structures in human thinking and make a system out of some explicit versions of those, you either get a system open-endedly searching for better structures (for which understanding the initial backbone does not bestow you with an understanding of the system), or you get an enfeebled shadow of human thought that doesn’t get anywhere.

- This self-reprogramming on many/all levels that is (?)required to make the system work needn't involve being explicitly able to change any important property one has. For instance, humans[56] are pretty wildly (self-)reprogrammable, even though there are many properties of, say, our neural reward systems which we cannot alter (yet) — but we can, for example, create contexts for ourselves in which different things end up being rewarded by these systems (like, if you enroll at a school, you might be getting more reward for learning; if you take a game seriously or set out to solve some problem, your reward system will be boosting stuff that helps you do well in that game or solve the problem); a second example: while we would probably want to keep our thinking close to our natural language for a long time, we can build wild ways to think about mathematical questions (or reorganize our thinking about some mathematical questions) while staying "inside/[adjacent to]" natural language; a third example: while you'd probably struggle to visualize 4-dimensional scenes[57], you might still be able to figure out what shape gets made if you hang a 4-dimensional hypercube from one vertex and intersect it with a "horizontal" hyperplane through its center.[58]

- Are these arguments strong enough that we should think that this kind of thing is not ever going to be remotely competitive? I think that's plausible. Should it make us think that there is no set of ideas which would get us some such crisp system which proves Fermat's last theorem with no more compute than fits in this galaxy (without us handing it the proof)? Idk, maybe — very universally quantified statements are scary to assert (well, because they are unlikely to be true). But minimally, it is very difficult.

- Anyway, if I were forced to give an eleven-word answer to “how does thinking work?”,[59] I’d say “one finds good components for thinking, and puts them to use”[60].

- But this finding of good components and putting them to use is not some definite finite thing; it is still an infinitely rich thing; there is a real infinitude of structure to employ to do this well. A human is doing this much better than a Jupiter-sized computer doing some naive program search, say.

- I'm dissatisfied with “one finds good components for thinking, and puts them to use” potentially giving the false impression that [what I'm pointing to must involve being conscious of the fact that one is looking for components or putting them to use], which is really a very rare feature among instances in the class I have in mind. Such explicit self-awareness is rare even among instances of finding good components for thinking which involve a lot of thought; here are some examples of thinking about how to think:

- a mathematician coming up with a good mathematical concept;

- seeing a need to talk about something and coining a word for it;

- a philosopher trying to clarify/re-engineer a concept, eg by seeing which more precise definition could accord with the concept having some desired "inferential role";[61]

- noticing and resolving tensions in one’s views;

- discovering/inventing/developing the scientific method; inventing/developing p-values; improving peer review;

- discussing what kinds of evidence could help with some particular scientific question;

- inventing writing; inventing textbooks;

- the varied thought that is upstream of a professional poker player thinking the way they do when playing poker;

- asking oneself "was that a reasonable inference?", “what auxiliary construction would help with this mathematical problem?”, "which techniques could work here?", "what is the main idea of this proof?", "is this a good way to model the situation?", "can I explain that clearly?", "what caused me to be confused about that?", "why did I spend so long pursuing this bad idea?", "how could I have figured that out faster?", “which question are we asking, more precisely?”, "why are we interested in this question?", “what is this analogous to?”, "what should I read to understand this better?", "who would have good thoughts on this?"[62].

- I prefer “one finds good components for thinking, and puts them to use” over other common ways to say something similar that I can think of — here are some: "(recursive )self-improvement”, “self re-programming”, “learning”, and maybe even "creativity" and "originality". I do also like “one thinks about how to think, and then thinks that way”.

- Even though intelligence isn't that much of a natural kind,[63] I think it makes a lot of sense for us to pay a great deal of attention to an artificial system which is smarter than humans/humanity being created. In that sense, there is a highly natural threshold of general intelligence which we should indeed be concerned about. I'll say more about this in Note 8. (Having said that thinking can only be infinitesimally understood and isn't even that much of a definite thing, let me talk about it for 20 more notes :).)

5 confusion isn't going away

- There's probably no broad tendency toward the elimination of confused thinking, despite us becoming less confused about any particular "finite question"; this has to do with our interests growing with our understanding/deconfusion.[64](or family of questions). We could call it "the convergence question" or "the compactness question".

- This really depends on the way we're measuring confusion (or its elimination), and different criteria could make sense for different purposes and give genuinely different verdicts, so I've been somewhat provocative here.[65]

- But I think this is probably true when we measure confusion around questions we're interested in (with the caveat that there can still be multiple sensible choices giving different answers here depending on what we're more precisely interested in, so I'm still being slightly provocative).

- One consideration here is that we're drawn to places where we're still confused, because that's where there are things to be worked out better. There's a messy confused frontier where we will hopefully be operating indefinitely (or at least until we're around, and if/when we aren't around anymore, other minds will be operating indefinitely at this frontier (until minds are around)).

- Another consideration is that mathematics and (relatedly, not independently) technological development provide an infinite supply of interesting things for us to be confused about.

- One more (related) consideration is that when we're trying to (eg) prove some theorem or to build some technology, we're likely to still be confused about stuff around it and about how to think well around it, because otherwise we'd already be done with it.

- One could try to work on a project of reorganizing thought which aims to push all confusion/ambiguity into probabilities on some hypothetical clear language, but such a project can't succeed in its aim,[66] because there are probably many interestingly different ways in which it is useful to be able to be confused.[67][68][69] You could probably pull off making an advanced mind with a clear structure where only a particular kind of confusion seems to be explicitly allowed, but to the extent that such a mind gets very far, I expect it will just be embedding other ways to think confusedly inside the technically-clear structure you technically-[forced it to have].

- All this isn't to say that we shouldn't be trying to become less confused about particular things. I think becoming less confused about particular things (richly conceived) is a central human project (and it is probably a central endeavor for ~all minds)!

- More generally, I doubt thinking is or is going to become very neatly structured — I think it'll probably always be a mess, like organic things in general.

- To consider an example somewhat distinct from confused thinking: will there be a point in time after which thinking-systems are (or the one big world-thinking-system is) partitioned into distinct thinking-components, each playing some clear role, fitting into some neat structure? I doubt there will be such an era (much like I doubt there will be such an era for the technological world more broadly), for one because it seems good to allow components to relate to other components in varied and unforeseen ways[70] (in particular, it is good to be able to make analogies to old things to understand new things; if we look at making an analogy from the outside, it is a lot like putting some old understanding-machinery to a new use).[71] So, thinking-structures will probably (continue to) relate to other thinking-structures in a multitude of ways, with each component playing many roles, and probably with the other components setting the context for each component, as opposed to there being some separate structure above all the components.

- That said, certainly there will also be many clean constellations of components in use (like current computer operating systems). Moreover, there are plausibly significant forces/reasons pushing toward thought being more cleanly organized — for instance: (1) cleaner organization could make thought easier to understand, improve, redeploy, control; (2) if some evolution-made thinking-structures in brains get replaced by ones which are more intelligently designed at some point, those would plausibly be made "in the image of some cleaner idea(s)" (compared to evolution's design, and at least in some aspects). It seems plausible that these forces would win [in some "places"]/[for/over some aspects of thought]. I'd like to be able to provide a better analysis of what the forces toward messiness and the forces toward order/structure add up to in various places — I don't think I'm doing justice to the matter here. In particular, I'd like to have a catalogue of comparisons between evolution-made and human-made things meeting some specifications.[72] I'd love to even just have a better catalogue of the [forces toward]/[reasons for] messiness and the [forces toward]/[reasons for] order/structure (not just in the context of thinking).

- Generally, I'd expect eliminating messy thinking-systems to be crippling, and eliminating clean systems to also be crippling. (I'd also expect eliminating confused thinking to be crippling, and eliminating rigorous/mathematico-logical speaking to be crippling.)

6 thinking (ever better) will continue

- Could history naturally consist of a period of thinking, of figuring stuff out — for example, of a careful long reflection lasting years, during which e.g. ethics largely "gets solved" — followed by a period of doing/implementing/enjoying stuff — maybe of tiling the universe with certain kinds of structures, or of luxury consumerism?

- Could history naturally consist of a period of fooming — that is, becoming smarter, self-reprogramming, finding and employing new thought-structures — followed by a period of doing/implementing/enjoying stuff — maybe of tiling the universe with certain kinds of structures, or of luxury consumerism?

- a mostly-aside: These two conceptions of history are arguably sorta the same, because figuring a lot of stuff out (decently quickly) requires a lot of self-reprogramming, and doing a lot of self-reprogramming (decently quickly) requires figuring a lot of stuff out. And really, one probably should think of gaining new understanding and self-reprogramming-to-think-better as the same thing to a decent approximation. I've included these as separate conceptions of history, because it's not immediately obvious that the two are the same, and in particular because one often conceives of a long reflection as somehow not involving very much self-reprogramming, and also because the point I want to make about these conceptions can stand without having to first establish that these are the same.

- It'd be profoundly weird for history to look like either of these, for (at least) the following reasons:

- There's probably no end to thinking/fooming.[73] There will probably always be major interesting problems to be solved, including practical problems — for one, because "how should one think?" is an infinite problem, as is building useful technologies more generally. Math certainly doesn't seem to be on a trajectory toward running out of interesting problems. There is no end to fooming, because one can always think much better.

- The doing/implementing/enjoying is probably largely not outside and after the thinking/fooming; these are probably largely the same thing. Thinking/fooming are kinds of doing, and most of what most advanced minds are up to and enjoy is thinking/fooming. In particular, one cares about furthering various intellectual projects, about becoming more skilled in various ways, which are largely fooming/working/thinking-type activities, not just enjoyment/tiling/enjoying-type activites.

- This is not to say that it'd be impossible for thinking or fooming to stop. For instance, an asteroid could maybe kill all humans or even all vertebrates, and there could be too little time left before Earth becomes inhospitable [for serious thought to emerge again on Earth after that]. Or we could maybe imagine a gray goo scenario, with stupid self-replicating nanobots eating Earth and going on to eat many more planets in the galaxy.[74] So, my claim is not that thinking and fooming will necessarily last forever, but that the natural trajectory of a mind does not consist of an era of thinking/fooming followed by some sort of thoughtless era of doing/implementing/enjoying.

- So, superintelligence is not some definite thing. If I had to compare the extent to which superintelligence is some definite thing to the extent to which general intelligence is some definite thing, I think I'd say that superintelligence is even less of a definite thing than general intelligence. There's probably not going to be a time after superintelligence develops, like, such that intelligence has now stopped developing. Similarly/equivalently, there's no such thing as a remotely-finished-product-[math ASI].

- All this said, it seems plausible that there'd be a burst of growth followed by a long era of slower growth (and maybe eventually decline) on measures like negentropy/energy use or the number of computational operations (per unit of time)[75] (though note also that the universe has turned out to be larger than one might have thought many times in the past and will plausibly turn out to be a lot larger again). It doesn't seem far-fetched that something a bit like this would also happen for intelligence, I guess.

- I should try to think through some sort of more careful economics-style analysis of the future of thinking, fooming, doing, implementing, enjoying. Like, forgetting for this sentence that these are not straightforwardly distinct things, if we were to force a fixed ratio of thinking/fooming to doing/implementing/enjoying, what should we expect the marginal "costs"/"benefits" to look like, and a shift in what direction away from the fixed ratio (and how big a shift) would that suggest?

- That said, even if this type of economic argument were to turn out to support thinking/fooming eventually slowing down relative to implementing/enjoying, I might still think that the right intuition to have is that there’s this infinite potential for thinking better anyway, but idk. And I'd still probably think we're probably not anywhere close (in "subjective time") to the end of thought/fooming.[76]

7 alignment is infinite

- What is "the alignment problem"?

- We could say that "the big alignment problem" is to make it so things go well around thinking better forever, maybe by devising a good protocol for adopting new [ways of thinking]/[thinking-structures]. I think this big alignment problem is probably in the "complexity class" of infinite problems described in thesis 1; so, we should perhaps say the "alignment endeavor" instead.

- There are also various "small alignment problems" — for instance, (1) there is the problem of creating a system smarter than humanity which is fine to create, and (2) there is the problem of ending the current period of (imo) unusually high risk of everything worthwhile being lost forever because of AI.[77] Problem (1) is quite solvable, because humanity-next-year will be such a system,[78] or because humans genetically modified to be somewhat smarter than the smartest humans currently alive would probably be fine to create, or because there is probably a kind of mind upload which is fine to create in some context which we could set up (with effort).[79] Problem (2) is also quite solvable, because conditional on it indeed being a very bad idea to make a smarter-than-human and non-human artifact, it is possible to get humanity to understand that it is a very bad idea and act responsibly given that understanding (ban AGI) and severely reduce the annual risk of everything meaningful being wiped out.

- Why is the big alignment problem infinite?

- It seems likely that one ought to be careful about [becoming smarter]/[new thinking/doing-structures coming into play] forever, and that this being careful just isn't the sort of thing for which a satisfactory protocol can be specified beforehand, but the sort of thing where indefinitely many arbitrarily different new challenges will need to be met as they come up, preferably with the full force of one's understanding at each future time (as opposed to being met with some fixed protocol that could be specified at some finite time). There is an infinitely rich variety of new ways of thinking that one should be open to adopting, and it'd be bizarre if decisions about this rich variety of things could be appropriately handled by any largely fixed protocol.

- to say more: There's no hope to well-analyze anything but an infinitesimal fraction of the genuinely infinite space of potential [thinking/doing]-structures, and it is hard to tell what needs to be worked out ahead of time. Well-handling a particular [thinking/doing]-structure often requires actually thinking about it in particular to a significant extent (though one can of course bring to bear a system of understanding built for handling previous things, also), and there's a tension in being able to do that significantly before the thinking-structure comes on the scene, because (1) if the structure can be seen clearly enough to be well-analyzed or even identified as worthy of attention, then it is often in use already in use or at least close to coming into use and (2) understanding it acceptably well often sorta requires playing around with it, so it must plausibly already be used (though maybe only "in a laboratory setting") for it to be adequately understood. Like, it's hard to imagine a bright person in 1900 identifying the internet as a force which should be understood and managed and going on to understand it adequately; it's hard to imagine someone before Euclid (or before whenever the axiomatic method in mathematics as actually developed) developing a body of understanding decent for understanding the axiomatic method in mathematics (except by developing the axiomatic method in mathematics oneself) (and many important things about it were in fact only understood two millennia later by Gödel and company); it's hard to imagine humans without language being well-prepared for the advent of language ahead of time (this is an example where the challenge is particularly severe). So, we should expect that in many cases, the capacity to adequately handle a novel [thinking/doing]-structure would only be developed only after it comes on the scene or as it is coming on the scene or only a bit before it comes on the scene.

- A potential response: "Okay, let's say I agree that there is this infinitely rich space of thinking-structures, and that one really just needs to keep thinking to handle this infinitely rich domain. But couldn't there be a finite Grand Method for doing this thinking?". My brief response is that this thinking will need to be rich and developing to be up to the challenge (as long as one is to continue to develop). It seems pretty clear that this question is roughly equivalent to "couldn't there be a Protocol for math/science?""; so, see Notes 1–6 for a longer response to this question. (And if you try to go meta more times, I'll just keep giving the same response. It's not like the higher meta-levels are any easier; actually, it's not even like we'd want them to be handled by some very distinct thinking.)

- This isn't to say that handling alignment well looks like handling an infinite variety of completely unique particulars (just like that's not what (doing) math looks like). One still totally can and totally should be developing methods/tools/ideas/understanding with broad applicability (just like one does in math) — it's just that this is an infinite endeavor. For example, I think it's a very good broadly applicable "idea" to become smarter oneself instead of trying to create some sort of benevolent alien entity. A further very good broadly applicable "idea" is to be extremely careful/thoughtful about becoming smarter as you are becoming smarter.

- Even though it's sort of confused to conceive of "the alignment problem" as a finite thing that could be solved, confused to imagine a textbook from the future solving alignment, it is totally sensible and very good for there to be a philosophico-scientifico-mathematical field that studies the infinitely rich variety of questions around how one[80] should become smarter (without killing/losing oneself too much). We could call that field "alignment".[81] (It might make sense for alignment to be a topic of interest for people in many fields, not a very separate field in its own right; it should probably be done by researchers that think also more broadly about how thinking works, and about many other philosophical and mathematical matters.)

- But again, for each particular time, the problem of making an intelligent system which is smarter than we are currently and which is fine to make is totally a finite problem, e.g. because it is fine to become smarter by doing/learning more math/science/philosophy. Also, one might even get to a position where one could reasonably think that things will probably be good over a very long stretch of gaining capabilities (I'm currently very uncertain here[82]). But even if this is possible, (I claim) this cannot be achieved by writing a textbook ahead of time for how to become smarter and just following that textbook (or having the protocol specified in this textbook in place) over a long stretch of time — as one proceeds, one will need to keep filling the shelves of an infinite alignment library with further textbooks one is writing.

- Let me speedrun some other interesting questions about which textbooks could be written. Of course, the questions really deserve much more careful treatment. In my answers in this speedrun (in particular, in the specification gaming I will engage in), I will be guided by some background views which I have not yet properly laid out or justified in this initial segment of the notes — specifically, including and surrounding the view that it is a tremendously bad idea to make an artifact which is more intelligent than us and distinct/separate from us any time soon (and maybe ever). But laying out and justifying these views better is a central aim of the remainder of these notes.

- "Is there some possible 100000-word text which would get us out of the present period of (imo) acute x-risk from artificial intelligence?" I think there probably is such a book, because if I'm indeed right that we are currently living through a period of acute risk, there could be a 100000-word text making a case for this which is compelling enough that it gets humanity to proceed with much more care; alternatively, one could specify a way to make humanity sufficiently smarter/wiser that we realize we are living through a period of acute risk ourselves (again, assuming this is indeed so); alternatively, one could give the most careful humans a "recipe" for mind uploads and instructions for how to set up a context in which uploading all humans meaningfully decreases x-risk (per unit of subjective time, anyway); etc — there is probably a great variety of 100000-word texts that would do this. Any such text has a probability of at least to be "written" by a (quantum) random number generator, so for any such text, there is at least this astronomically small probability we would "write it" ourselves (lol); but really, I think it is realistically possible (idk, like, if we try?) for us to write any of the example texts from the previous sentence ourselves.

- "But is there a text which lets us make an AI which brings our current era of high x-risk to a close?" Sorta yes, e.g. because mind uploads are possible and knowing how to make mind uploads could get us to a world where most people are uploaded and become somewhat better at thinking and understand that allowing careless fooming is a bad idea (assuming it indeed is a bad idea) and such a world would plausibly have lower p-doom per subjective year (especially if the textbook also provides various governance ideas) :).

- "But is there one which lets us make a much more alien mind which is smarter than us which is good to make?" Sorta yes, e.g. because we could still have the alien mind output a different book and self-destruct :).

- "Argh, but is there a text which lets us make a more alien mind which is smarter than us and good to make which then directly does big things in the world (+ additional conditions to prevent further specification gaming) which is good to make?" I think there probably is a text which would give the source code of a mind which is already somewhat smarter than us, which is only becoming smarter in very restricted ways, and which does nothing except destroying any AGIs that get built, withstanding human attempts to disable it for a century (without otherwise doing anything bad to humans) and then self-destructing.[83]

- "But is there a text which looks like a textbook (so, not like unintelligible source code) which lets us understand relevant things well enough that we can build an alien AI that does the thing you stated in the previous response?"[84] Now that the textbook cannot directly provide advanced understanding that the AI could use and it probably needs to become really smart from scratch and we cannot be handed a bespoke edit to make to the AI which makes it "sacrifice itself" for us this way, it seems much tougher, but I guess it's probably possible, even though I lack any significantly "constructive" argument. I'm very unsure/confused about whether there will ever be a time in future history when we could reasonably write this kind of text ourselves (such that it is adequate for our situation then). I think it's plausible that there will be no future point at which we should try to execute a plan of this kind that we devised ourselves (over continuing to do something that looks much more like becoming smarter ourselves[85]).