The theory of ‘morality as cooperation’ (MAC) argues that morality is best understood as a collection of biological and cultural solutions to the problems of cooperation recurrent in human social life. MAC draws on evolutionary game theory to argue that, because there are many types of cooperation, there will be many types of morality. These include: family values, group loyalty, reciprocity, heroism, deference, fairness and property rights. Previous research suggests that these seven types of morality are evolutionarily-ancient, psychologically-distinct, and cross-culturally universal. The goal of this project is to further develop and test MAC, and explore its implications for traditional moral philosophy. Current research is examining the genetic and psychological architecture of these seven types of morality, as well as using phylogenetic methods to investigate how morals are culturally transmitted. Future work will seek to extend MAC to incorporate sexual morality and environmental ethics. In this way, the project aims to place the study of morality on a firm scientific foundation.

Source: https://www.lse.ac.uk/cpnss/research/morality-as-cooperation.

Do you notice your beliefs changing overtime to match whatever is most self-serving? I know that some of you enlightened LessWrong folks have already overcome your biases and biological propensities, but I notice that I haven't.

Four years ago, I was a poor university student struggling to make ends meet. I didn't have a high paying job lined up at the time, and I was very uncertain about the future. My beliefs were somewhat anti-big-business and anti-economic-growth.

However, now that I have a decent job, which I'm performing well at, my views have shifted towards pro-economic-growth. I notice myself finding Tyler Cowen's argument that economic growth is a moral imperative quite compelling because it justifies my current context.

The general strategy is to have fewer beliefs, to allow development of detailed ideas/hypotheses/theories without giving much attention to evaluation of their external correctness (such as presence of their instances in the real world, or them making sense in other paradigms you understand), instead focusing on their internal correctness (validity of arguments inside the idea, from the point of view of a paradigm/mindset native to the idea). Then you only suffer motivated attention, and it's easier to counter by making sure to pay some attention to developing understanding of alternatives.

The results look pretty weird though, for example I imagine that there might be a vague impression from my writings that I'm changing my mind on topics that I've thought about for years back and forth on months-long scale, or believe contradictory things at the same time, or forget some fundamental well-known things (paradigms can insist on failing to understand/notice some established facts, especially when their well-being depends on it). I'm not sure how to communicate transient interest in an obscure idea without it coming across as a resurgent belief in it (with a touch of amnesia to other things), and I keep using belief-words to misleadingly describe beliefs that only hold inside an idea/hypothesis/theory too. (This is not something language has established conventions for.)

Let me try to apply this approach to my views on economic progress.

To do that, I would look at the evidence in favour of economic progress being a moral imperative (e.g. improvements in wellbeing) and against it (development of powerful military technologies), and then make a level-headed assessment that's proportional to the evidence.

It takes a lot of effort to keep my beliefs proportional to the evidence, but no one said rationality is easy.

I don't see it. The point of the technique is to defer your own judgement on arguments/claims/facts that live inside of theories indefinitely, giving them slack to grow according to theory's own perspective (for months and years). Instead of judging individual arguments in their own right, according to your own worldview, you judge them within the theory, from the theory's weird perspective you occasionally confidently disagree with. Less urgently, you also judge the theory as a whole according to your own worldview. If it's important/interesting, or has important/interesting competitors, then you keep developing it, even if it doesn't look promising as a whole (some of its internally-generated arguments will survive its likely demise).

The point that should help with motivated cognition is switching between different paradigms/ideologies that focus on theories that compete with a suspect worldview, so that a germ of truth overlooked in its misguided competitors won't be indefinitely stunted in its development. On 5-second level, the skill is to maintain a two-level context, with description of the current theory/paradigm/ideology/hypothesis at the top level, and the current topic/argument/claim at the lower level.

There are two modes in which claims of the theory are judged. In the internal mode, you are channeling the theory, taking Ideological Turing Test for it, thinking in character rather than just thinking, considering the theory's claims according to the theory itself, to change them and develop the theory without affecting their growth with your own perspective and judgement. This gives the arguments courage to speak their mind, not worrying that they are disbelieved or disapproved-of by external-you.

In the external mode, you consider claims made by the theory from your own perspective and treat them as predictions. When multiple theories make predictions about the same claim, and you are externally confident in its truth, that applies a likelihood ratio to external weights of the theories as wholes, according to their relative confidence in the claim. This affects standing of the theories themselves, but shouldn't affect the standing of the claims within the theories. (The external weights of theories are much less important than details of arguments inside the theories, because there is all sorts of filtering and double counting, and because certain falsity of a theory is not sufficient for discarding it. But it's useful to maintain some awareness of them.)

[Minor spoiler alert] I've been obsessed with Dune lately. I watched the movie and read the book and loved both. Dune contains many subtle elements of rationality and x-risks despite the overall mythological/religious theme. Here are my interpretations: the goal of the Bene Gesserit is to selectively breed a perfect Bayesian who can help humanity find the Golden Path. The Golden Path is the narrow set of futures that don't result in an extinction event. The Dune world is mysteriously and powerfully seductive.

I think you're reading that into it. No one before Leto II shows any awareness of Kralizec or the inevitable extinction of humanity at the hands of prescient machines invented by the Ixians (and given the retroactive prescience dynamics, unclear if anyone even could). The BG's stated goals are always to make humanity grow up into 'adults', equipped for the challenges of a radically open infinite universe; this ultimately contributes to Leto's plans, but that was not the BG's intention, and they were pawns of prescience starting before Dune when Paul retrocauses himself to be born instead of some Paulina as the BG had planned. (The Golden Path is narrow because it requires 3 different very improbable events: the invention of the Siona gene and No-fields/ships, and the Scattering. The former two ensure that no possible future prescient power, particularly machine ones, can ever, anywhere in any possible future, control probability to create a new self-consistent history by reaching back to prune away all possible futures not leading to human defeat and then guiding the machines to their targets everywhere; the last ensures that humanity is exponentially expanding at a sufficient rate randomized throughout the infinite universe that no non-prescient extinction wave can ever catch up to extinct all human planets.)

Herbert doesn't think this is confined solely to mere reasoning, Bayesian or otherwise; if he had, Mentats (technology/computation) would be the ne plus ultra of the universe. Instead, they, as well as the Sword Masters (military), Honored Matres (politics=sex, see Walter's Sexual Cycle), Bene Tleilaxu (genetics & manipulation of biology) / ascended Face Dancers, Bene Gesserit (sociology & control of bodies), access to the knowledge of Ancestral Memories etc, are all part of the toolbox. Later humans are not just smart and more rational and more observant, but physically faster, stronger, and more dexterous.

I just came across Lenia, which is a modernisation of Conway's Game of Life. There is a video by Neat AI explaining and showcasing Lenia. Pretty cool!

On the mating habits of the orb-weaving spider:

These spiders are a bit unusual: females have two receptacles for storing sperm, and males have two sperm-delivery devices, called palps. Ordinarily the female will only allow the male to insert one palp at a time, but sometimes a male manages to force a copulation with a juvenile female, during which he inserts both of his palps into the female’s separate sperm-storage organs. If the male succeeds, something strange happens to him: his heart spontaneously stops beating and he dies in flagrante. This may be the ultimate mate-guarding tactic: because the male’s copulatory organs are inflated, it is harder for the female (or any other male) to dislodge the dead male, meaning that his lifeless body acts as a very effective mating plug. In species where males aren’t prepared to go to such great lengths to ensure that they sire the offspring, then the uncertainty over whether the offspring are definitely his acts as a powerful evolutionary disincentive to provide costly parental care for them.

The lack of willpower is a heuristic which doesn’t require the brain to explicitly track & prioritize & schedule all possible tasks, by forcing it to regularly halt tasks—“like a timer that says, ‘Okay you’re done now.’”

If one could override fatigue at will, the consequences can be bad. Users of dopaminergic drugs like amphetamines often note issues with channeling the reduced fatigue into useful tasks rather than alphabetizing one’s bookcase.

In more extreme cases, if one could ignore fatigue entirely, then analogous to lack of pain, the consequences could be severe or fatal: ultra-endurance cyclist Jure Robič would cycle for thousands of kilometers, ignoring such problems as elaborate hallucinations, and was eventually killed while cycling.

The ‘timer’ is implemented, among other things, as a gradual buildup of adenosine, which creates sleep homeostatic drive pressure and possibly physical fatigue during exercise (Noakes 2012, Martin et al 2018), leading to a gradually increasing subjectively perceived ‘cost’ of continuing with a task/staying awake/continuing athletic activities, which resets when one stops/sleeps/rests. (Glucose might work by gradually dropping over perceived time without rewards.)

Since the human mind is too limited in its planning and monitoring ability, it cannot be allowed to ‘turn off’ opportunity cost warnings and engage in hyperfocus on potentially useless things at the neglect of all other things; procrastination here represents a psychic version of pain.

Source: https://gwern.net/Backstop

I recently read Will Storr's book "The Status Game" based on a LessWrong recommendation by user Wei_Dai. It's an excellent book, and I highly recommend it.

Storr asserts that we are all playing status games, including meditation gurus and cynics. Then he classifies the different kinds of status games we can play, arguing that "virtue dominance" games are the worst kinds of games, as they are the root of cancel culture.

Storr has a few recommendations for playing the Status Game to result in a positive-sum. First, view other people as being the heroes of their own life stories. If everyone else is the hero of their own story, which character do you want to be in their lives? Of course, you'd like to be a helpful character.

Storr distils what he believes to be "good" status games into three categories. They are:

- Warmth: When you are warm, you communicate, "I'm not going to play a dominance game with you." You imply that the other person will not get threats from you and that they are in a safe place around you.

- Sincerity: Sincerity is about levelling with other people and being honest with them. It signals to someone else that you will tell them when things are going badly and when things are going well. You will not be morally unfair to them or allow resentment to build up and then surprise them with a sudden burst of malice.

- Competence: Competence is just success and it signals that you can achieve goals and be helpful to the group.

I thought this book offered an interesting perspective on an integral aspect of being a human, status.

The important fact about "zero-sum" games is that they often have externalities. Maybe status is a zero-sum game in the sense that either you are higher-status than me, or the other way round, but there is no way for everyone to be at the top of the status ladder.

However, the choice of "weapons" in our battle matters for the environment. If people can only get higher status by writing good articles, we should expect many good articles to appear. (Or, "good" articles, because goodharting is a thing.) If people can get higher status by punching each other, we should expect to see many people hurt.

According to Adam Smith, the miracle of capitalism is channeling the human instinct of greed into productive projects. (Or, "productive", because goodharting is a thing.) We should do the same thing for status, somehow. If we could universally make useful things high-status and harmful things low-status, the world would become a paradise. (Or, a "paradise", because goodharting is a thing.)

How to do that, though? One obvious problem is that you cannot simply set the rules for people to follow, because "breaking rules" is inherently high-status. Can you make cheaters seem like losers, even if it brings them profit (because otherwise, why would they do it)?

Loved your comment, especially the “goodharting” interjections haha.

Your comment reminded me of “building” company culture. Managers keep trying to sculpt a company culture, but in reality managers have limited control over the culture. Company culture is more a thing that happens and evolves, and you as an individual can only do so much to influence it this way or that way.

Similarly, status is a thing that just happens and evolves in human society, and sometimes it has good externalities and other times it has bad externalities.

I quite liked “What You Do Is Who You Are” by Ben Horowitz. I thought it offered a practical perspective on creating company culture by focusing on embodying the values you’d like to see instead of just preaching them and hoping others embody them.

I thought it offered a practical perspective on creating company culture by focusing on embodying the values you’d like to see instead of just preaching them and hoping others embody them.

That sounds like an advice on parenting. What your kids will do, is what they see you doing. Actually no, that would be too easy -- your kids will instead do a more stupid version of what they see you doing. Like, you use a swear word once in a month, but then they will keep using it every five minutes.

And, I don't know, maybe this is where the (steelman of) preaching is useful; to correct the exaggerations. Like, if you swear once in a while, you will probably fail to convince your kids that they should never do that; copying is a strong instinct. But if you tell them "okay kids, polite people shouldn't be doing this, and yes I do it sometimes, but please notice that it happens only on some days, not repeatedly, and not in front of your grandparents or teachers -- could you please follow the same rules?" then maybe at some age this would work. At least it does not involve denying the reality.

And maybe the manager could say something like "we said that we value X, and yes, we had this one project that was quite anti-X, but please notice that most of our projects are actually quite X, this one was an exception, and we will try having fewer of that in the future". Possibly with a discussion on why that one specific project ended up anti-X, and what we could do to prevent that from happening in the future.

Managers keep trying to sculpt a company culture, but in reality managers have limited control over the culture. Company culture is more a thing that happens and evolves, and you as an individual can only do so much to influence it this way or that way.

Intentionally influencing other people is a skill I lack, so I can only guess here. It seems to me that although no manager actually has the whole company perfectly under control, there are still some more specific failure modes that are quite common:

- Some people are obvious bullshitters, and if you are familiar with this type, you just won't take any of their words seriously. Their lips just produce random syllables that are supposed to increase your productivity, or maybe just signal to their boss that they are working hard to increase your productivity, but the actual meaning of the words is completely divorced from reality. (For example, the managers who regularly give company speeches on the importance of "agile development", and yet it is obvious that they intend to keep all 666 layers of management, and plan everything 5 years ahead... but now you will have Jira and daily meetings, in addition to all the usual meetings, so at least that will be different.)

- Some people seem to actually mean it, but they fail to realize that incentives matter, or that in order to achieve X you actually need to do some Y first, as if the mere act of stating your goal could magically make it true. (For example, the managers who keep talking about how work-life balance is important, and yet all their teams are understaffed, and they keep starting new projects without cancelling the existing ones or hiring more people. Or the managers who tell you to give honest estimates how long something will take, but they consistently punish employees who say that something will take a lot of time, even if they turn out to be right, and reward employees who give short estimates, even if they fail to deliver the expected quality.) Here I am sometimes not sure what is actual incompetence, and what just strategical pretense.

I may be unfair, but the older I get, the more I assume that most dysfunctions at workplace are there by design, not by accident. Not necessarily for the good of the company, but rather for personal benefit of some of its managers, like making their job more convenient, or getting a bonus for bringing short-term profit (that will lead to long-term loss, but someone else will be blamed for that).

Elephant in the Brain influenced extensively ways I perceive social motivations. It is talking exactly about the same subject and mechanisms of why we don't discern it in ourselves. If you didn't read it you should check it out. It rewrote my views to the extent that I feel afraid to read "The status game" because it feels so easy to fall into confirmation bias here. This seems to me so active that I would love to read something opposite. Are there any good critiques of this view? Once I was listening to Frans de Waal's lecture when he expressed this confusion that in primatology almost everything is explained through the hierarchy in the group. But when we listen to social scientists almost none of it is. Elephant in the brain. I think this is such an important topic.

I've read "The Elephant in the Brain", and it was certainly a breathtaking read. I should read it again.

While reading the book "Software Engineering at Google" I came across this and thought it was funny:

Some languages specifically randomize hash ordering between library versions or even between execution of the same program in an attempt to prevent dependencies. But even this still allows for some Hyrum’s Law surprises: there is code that uses hash iteration ordering as an inefficient random-number generator. Removing such randomness now would break those users. Just as entropy increases in every thermodynamic system, Hyrum’s Law applies to every observable behavior.

It is beyond me why anyone would use hashset ordering as a random number generator! But that is why Hyrum's Law is a law and not some other thing that's not a law. For context, Hyrum's Law states:

With a sufficient number of users of an API, it does not matter what you promise in the contract: all observable behaviors of your system will be depended on by somebody.

A common criticism of rationality I come across rests upon the absence of a single, ultimate theory of rationality.

Their claim: the various theories of rationality offer differing assertions about reality and, thus, differing predictions of experiences.

Their conclusion: Convergence on objective truth is impossible, and rationality is subjective. (Which I think is a false conclusion to draw).

I think that this problem is congruent to Moral Uncertainty. What is the solution to this problem? Does a parliamentary model similar to that proposed by Bostrom and Ord make sense here? I am sure this problem has been talked about on LessWrong or elsewhere. Please direct me to where I can learn more about this!

I would like to improve my argument against the aforementioned conclusion. I would like to understand this problem

I would like to improve my argument against the aforementioned conclusion.

An unrelated musing: Improving arguments for a particular side is dangerous, but I think a safe alternative is improving gears for a particular theory. The difference is that refinement of a theory is capable of changing its predictions in unanticipated ways. This can well rob it of credence as it's balanced against other theories through prediction of known facts.

In another way, gears more directly influence understanding of what a theory says and predicts, the internal hypothetical picture, not its credence, the relation of the theory to reality. So they can be a safe enough distance above the bottom line not to be mangled by it, and have the potential to force it to change, even if it's essentially written down in advance.

Thank you for the thoughtful response Vladimir.

I should have worded that last sentence differently. I agree with you that the way I phrased it sounds like I have written at the bottom of my sheet of paper .

I am interested in a solution to the problem. There exist several theories of epistemology and decision theory and we do now know which is "right." Would a parliamentary approach solve this problem?

This is not an answer to my question but a follow-up elaboration.

This quote by Jonathan Rauch from The Constitution of Knowledge attempts to address this problem:

Francis Bacon and his followers said that scientific inquiry is characterized by experimentation; logical positivists, that it is characterized by verification; Karl Popper and his followers, by falsification. All of them were right some of the time, but not always. The better generalization, perhaps the only one broad enough to capture most of what reality-based inquirers do, is that liberal science is characterized by orderly, decentralized, and impersonal social adjudication. Can the marketplace of persuasion reach some sort of stable conclusion about a proposition, or tackle it in an organized, consensual way? If so, the proposition is grist for the reality-based community, whether or not a clear consensus is reached.

However, I don't find it satisfying. Rauch focuses on persuasion and ignores explanatory power. It reminds me of this claim from The Enigma of Reason, stating:

Whereas reason is commonly viewed as a superior means to think better on one’s own, we argue that it is mainly used in our interactions with others. We produce reasons in order to justify our thoughts and actions to others and to produce arguments to convince others to think and act as we suggest.

I will stake a strong claim: lasting persuasion is the byproduct of good explanations. Assertions that achieve better map-territory convergence or are more effective at achieving goals tend to be more persuasive in the long run. Galileo's claim that the Earth moved around the Sun was not persuasive in his day. Still, it has achieved lasting persuasion because it is a map that reflects the territory more accurately than preceding theories.

It might very well be the case that the competing theories of rationality all boil down to Bayesian optimality, i.e., generating hypotheses and updating the map based on evidence. However, not everyone is satisfied with that theory. I keep seeing the argument that rationality is subjective because there isn't a single theory, and therefore convergence on a shared understanding of reality is impossible.

A parliamentary model with delegates corresponding to the competing theories being proportional to some metric (e.g. track record of prediction accuracy?) explicitly asserts that rationality is not dogmatic; rationality is not contingent on the existence of a single, ultimate theory. This way, the aforementioned arguments against rationality dissolve in their own contradictions.

Rationality is the quality of ingredients of cognition that work well. As long as we don't have cognition figured out, including sufficiently general formal agents based on decision theory that's at the very least not in total disarray, there is also no clear notion of rationality. There's only the open problem of what it should be, some conjectures as to the shape it might take, and particular examples of cognitive tools that seem to work.

Almost any technology has the potential to cause harm in the wrong hands, but with [superintelligence], we have the new problem that the wrong hands might belong to the technology itself.

Excerpt from "Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach" by Norvig and Russell.

I wish moneymaking was by default aligned with optimising for the "good". That way, I can focus on making money without worrying too much about the messiness of morality. I wholly believe that existential risks are unequivocally the most critical issues of our time because the cost of neglecting them is so enormous, and my rational self would like to work directly on reducing them. However, I'm also profoundly programmed through millions of years of evolution to want a lovely house in the suburbs, a beautiful wife, some adorable children, lots of friends, etc. I do not claim that the two are impossible to reconcile. Instead, I argue that it's easier to achieve status maximising goals without caring too much about the morality of my career. I'd like to not feel guilty for my natural propensity toward earning more status. (When I say status, I don't mean rationality community status, I mean broader society status.)

Note that this is a complaint about morality, not about moneymaking.

Making money is aligned with satisfying some desires of some people. But morality is all about the messiness of divergent and unaligned humans and sets of humans (and non-human entities and future/potential humans who don't have any desires yet, but will at some point).

That's an eloquent way of describing morality.

It would be so lovely had we lived in a world where any means of moneymaking helped us move uphill on the global morality landscape comprising the desires of all beings. That way, we can make money without feeling guilty about doing it. Designing a mechanism like this is probably impossible.

Recently I came across this brilliant example of avoiding reducing selection bias when extracting quasi-experimental data from the world towards the beginning of the book "Good Economics for Hard Times" by Banerjee and Duflo.

The authors were interested in understanding the impact of migration on income. However, most data on migration contains plenty of selection bias. For example, people who choose to migrate are usually audacious risk-takers or have the physical strength, know-how, funds and connections to facilitate their undertaking,

To reduce these selection biases, the authors looked at people forced to relocate due to rare natural disasters, such as volcano eruptions.

Doesn't this still have selection bias, just of a different form?

For an obvious example, a little old granny who can barely walk is far less likely to (successfully) relocate due to a volcano eruption than a 25y old healthy male.

A missing but essential detail: the government compensated these people and provided them with relocation services. Therefore, even the frail were able to relocate.

That does help reduce the selection bias; I don't see why that would eliminate it?

I was more focused on chance of death not financials. The chance of said little old granny dying before being settled, either on the way or at the time of the initial event, is likely higher than the chance of the 25y old healthy male.

Oh, it wouldn't eliminate all selection bias, but it certainly would reduce it. I said "avoid selection bias," but I changed it to "reduce selection bias" in my original post. Thanks for pointing this out.

It's tough to extract completely unbiased quasi-experimental data from the world. A frail elder dying from a heart attack during the volcanic eruption certainly contributes to selection bias.

It's tough to extract completely unbiased quasi-experimental data from the world.

Understatement.

I can't go into more details here unfortunately, and some of the details are changed for various reasons, but one of the best examples I've seen of selection bias was roughly the following:

Chips occasionally failed. When chips failed, they were sent to FA[1] where they were decapped[2] and (destructively) examined[3] to see what went wrong. This is a fairly finicky process[4], and about half the chips that went through FA were destroyed in the FA process without really getting any useful info.

Chips that went through FA had a fairly flat failure profile of various different issues, none of which contributed more than a few percent to the overall failure rate.

Only... it turns out that ~40% of chip failures shared a single common cause. Turns out there was an issue that was causing the dies to crack[5], and said chips FA received then promptly discarded because they thought they had cracked the die during the FA process. (FA did occasionally crack the dies, but at about an order of magnitude lower rate than they had thought.)

I sometimes wondered why mathematicians are so pedantic about proofs. Why can't we just check the first cases with a supercomputer and do without rigorous proofs? Here's an excellent example of why proofs matter.

Consider this proposition: .

If you check with a computer, then this proposition will appear true.

The smallest counterexample has more than 1000 digits, and your computer program might not have checked that far. If you relied on the assumption that this equation has no solution in a cryptographic application without a proof, the consequences could be catastrophic.

That's fascinating. Thanks for sharing. Number theory is mindblowing. The integers look very simple at first glance, but they contain immense complexity and structure.

When some people hear the words "economic growth" they imagine factories spewing smoke into the atmosphere:

This is a false image of what economists mean by "economic growth". Economic growth according to economists is about achieving more with less. It's about efficiency. It is about using our scarce resources more wisely.

The stoves of the 17th century had an efficiency of only 15%. Meanwhile, the induction cooktops of today achieve an efficiency of 90%. Pre-16th century kings didn't have toilets, but 54% of humans today have toilets all thanks to economic progress.

Efficiency, if harnessed safely, benefits us all. It means we can get more value for less scarce resources, thus increasing the overall pie.

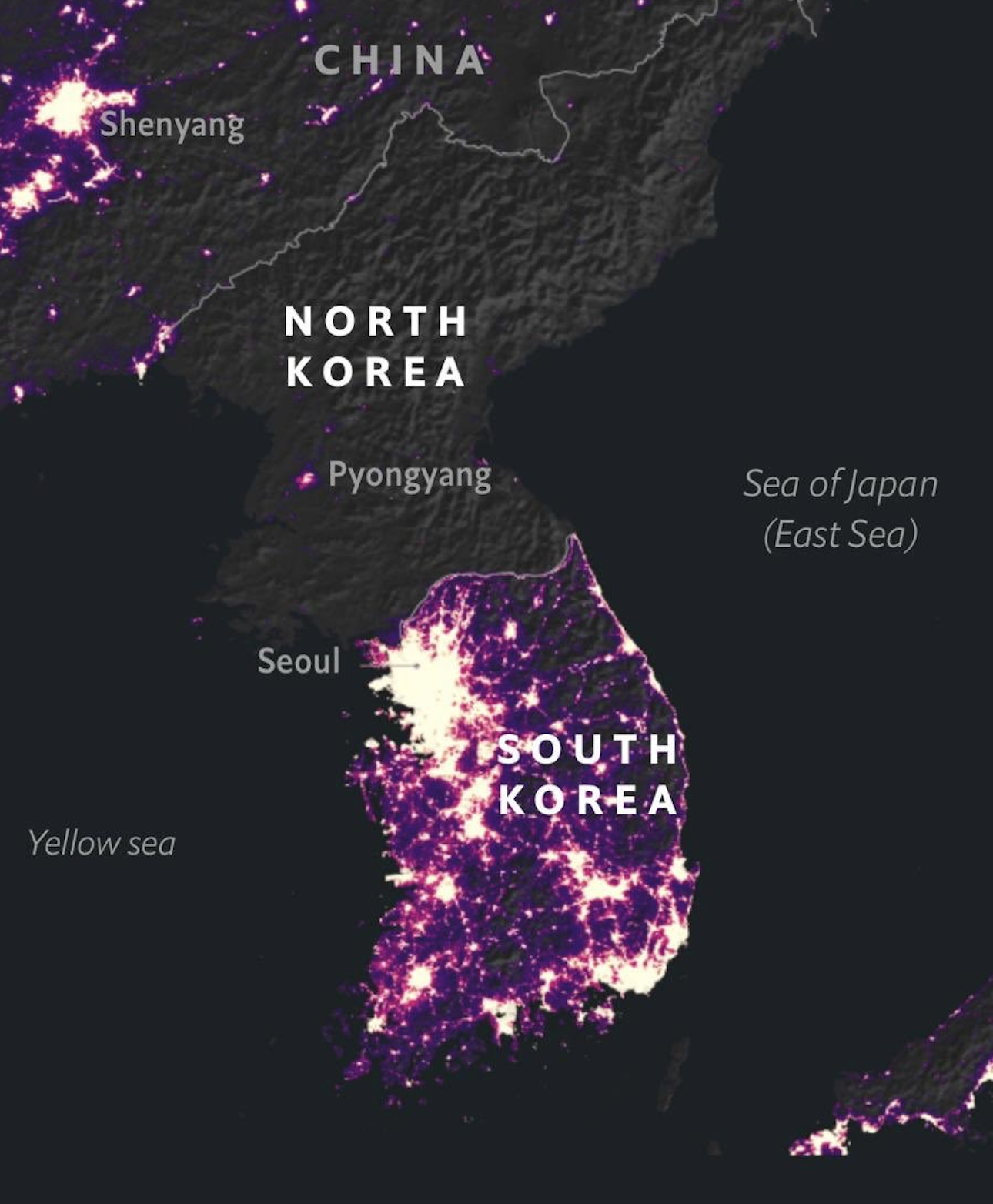

Will economic growth create more inequality due to rent seeking and wealth concentration? The evidence suggests that as GDP (not a perfect measure, but a decent one) grows, per capita incomes also grow. I’d rather be a peasant in South Korea than an average government employee in North Korea.

This is a list of the top 100 most cited scientific papers. Reading all of them would be a fun exercise.

I bet that most of them would replicate flawlessly. Boring lab techniques and protein structure dominate the list, nothing fancy or outlandish. Interestingly, the famous papers like relativity, expansion of the universe, the discovery of DNA etc. don't rank anywhere near the top 100. There is also a math paper on fuzzy sets among the top 100. Now that's a paper that definitely replicates!

That link didn't work for me somehow but I managed to find the spreadsheet with the 100 articles: https://www.nature.com/news/polopoly_fs/7.21247!/file/WebofSciencetop100.xlsx

According to Wikipedia, the most significant known prime number at this moment in time is . This is a nice illustration of two phenomena:

- The profound unpredictability of the growth of knowledge. If we can predict the next prime, then we should know what it is, but we don't.

- It tells us something profound about the reality of (Platonic) abstractions. We know that a more significant prime number must exist (there are infinitely many primes), but we just haven't found it yet. But we know it's out there in reality.

Is bias within academia ever actually avoidable?

Let us take the example of Daniel Dennett vs David Chalmers. Dennett calls philosophical zombies an "embarrassment," while Chalmers continues to double-down on his conclusion that consciousness cannot be explained in purely physical terms. If Chalmers conceded and switched teams, then he is going to be "just another philosopher," while Dennett achieves an academic victory.

As an aspiring world-class philosopher, you have little incentive to adopt the dominant view because if you do you will become just another ordinary philosopher. By adopting a radically different stance, you establish an entirely new "school" and become at its helm. Meanwhile, it would be considerably more effortful to become at the helm of the more well-established schools, e.g. physicalism and compatibilism.

Thus, motivated skepticism and motivated reasoning seem to me to be completely unavoidable in academia.

Are you sure that's an argument for it being completely unavoidable, or just an argument that our current incentive structures are not very good?

It surely is an incentive structure problem. However, I am uncertain about to what extend incentive structures can be "designed". They seem to come about as a result of thousands of years of culture gene coevolution.

Peer reviews have a similar incentive structure misalignment. Why would you spend a month reviewing someone else's paper when you can write your own instead? This point was made by Scott Aaronson during one of his AMAs but he didn't attempt at offering a solution.

Do we need more academics that agree with the status quo? If you reframe your point as "academia selects for originality," it wouldn't seem such a bad thing. Research requires applied creativity: creating new ideas that are practically useful. A researcher who concludes that the existing solution to a problem is the best is only marginally useful.

The debate between Chalmers and Dennett is practically useful, because it lays out the boundaries of the dispute and explores both sides of the argument. Chalmers is naturally more of a contrarian and Dennett more of a small c conservative; people fit into these natural categories without too much motivation from institution incentives.

The creative process can be split into idea generation and idea evaluation. Some people are good at generating wacky, out-there ideas, and others are better at judging the quality of said ideas. As De Bono has argued, it's best for there to be some hygiene between the two due to the different kinds of processing required. I think there's a family resemblence here with exploration-explotation trade-offs in ML.

TL;DR I don't think that incentives are the only constraint faced by academia. It's also difficult for individual people to be the generators and evaluators of their own ideas, and both processes are necessary.

Do rational communities undervalue idea generation because of their focus on rational judgement?

You make excellent points. The growth of knowledge is ultimately a process of creativity alternating with criticism and I agree with you that idea generation is under appreciated. Outlandish ideas are met with ridicule most of the time.

This passage from Quantum Computing Since Democritus by Scott Aaronson captures this so well:

[I have changed my attitudes towards] the arguments of John Searle and Roger Penrose against “strong artificial intelligence.” I still think Searle and Penrose are wrong on crucial points, Searle more so than Penrose. But on rereading my 2006 arguments for why they were wrong, I found myself wincing at the semi-flippant tone, at my eagerness to laugh at these celebrated scholars tying themselves into logical pretzels in quixotic, obviously doomed attempts to defend human specialness. In effect, I was lazily relying on the fact that everyone in the room already agreed with me – that to these (mostly) physics and computer science graduate students, it was simply self-evident that the human brain is nothing other than a “hot, wet Turing machine,” and weird that I would even waste the class's time with such a settled question. Since then, I think I’ve come to a better appreciation of the immense difficulty of these issues – and in particular, of the need to offer arguments that engage people with different philosophical starting-points than one's own.

I think we need to strike a balance between the veracity of ideas and tolerance of their outlandishness. This topic has always fascinated me but I don't know of a concrete criterion for effective hypothesis generation. The simplicity criterion of Occam's Razor is ok but it is not the be-all end-all.

I keep coming across the opinion that physics containing imaginary numbers is somehow a crazy and weird phenomenon, such as this article.

Complex numbers are an excellent tool for modelling rotations. When we multiply a vector by , we effectively rotate it anticlockwise by 90 degrees around the origin. Rotations are everywhere in reality, and it's thus unsurprising that a tool that's good at modelling rotations shows up in things like the Schrödinger Equation.

The article was weird because it implied you couldn't do without them, before backing off. 'Physicist says math with imaginary numbers is more beautiful than alternatives.'

Exactly. We can replace the use of imaginary numbers with matrix operations.

Schrödinger himself was annoyed by the imaginary part in his equation. In a letter to Lorentz on 6 June, 1926, Schrödinger wrote:

What is unpleasant here, and indeed directly to be objected to, is the use of imaginary numbers. is surely fundamentally a real function”.

Surely he knew that he could have done without imaginary numbers.

I find it helpful to think about probabilities as I think about inequalities. If we say that , then we are making an uncertain claim about the possible values of , but we have no idea what value actually has. However, from this uncertain claim about the value of , we can make the true claim that .

Similarly, when we prove that a probability is nonzero, it means that whatever it is we are talking about must be true somewhere within possibility space.

What causes us to sometimes try harder? I play chess once in a while, and I've noticed that sometimes I play half heartedly and end up losing. However, sometimes, I simply tell myself that I will try harder and end up doing really well. What's stopping me from trying hard all the time?

Fascinating question, Carmex. I am interested in the following space configurations:

- Conservation: when a lifeform dies, its constituents should not disappear from the system but should dissipate back into the background space.

- Chaos: the background space should not be empty. It should have some level of background chaos (e.g. dispersive forces) mimicking our physical environment.

I'd imagine that you'd have to encode a kind of variational free energy minimisation to enable robustness against chaos.

I might play around with the simulation on my local machine when I get the chance.

A map displaying the prerequisites of the areas of mathematics relevant to CS/ML:

A dashed line means this prerequisite is helpful but not a hard requirement.

It might be possible to find such ordering for specific textbooks, but this doesn't make much sense on the level of topics. It helps to know a bit of each topic to get more out of any other topic, so it's best to study most of these in parallel. That said, it's natural to treat topology as one of the entry-level topics, together with abstract algebra and analysis. And separate study of set theory and logic mostly becomes relevant only at a more advanced level.

Thanks for your insights Vladimir. I agree that Abstract Algebra, Topology and Real Analysis don’t require much in terms of prerequisites, but I think without sufficient mathematical maturity, these subjects will be rough going. I should’ve made clear that by “Sets and Logic” I didn’t mean a full fledged course on Advanced Set Theory and Logic, but rather simple familiarity with the axiomatic method through books like Naive Set Theory by Halmos and Book of Proof by Hammack.