When is Goodhart catastrophic?

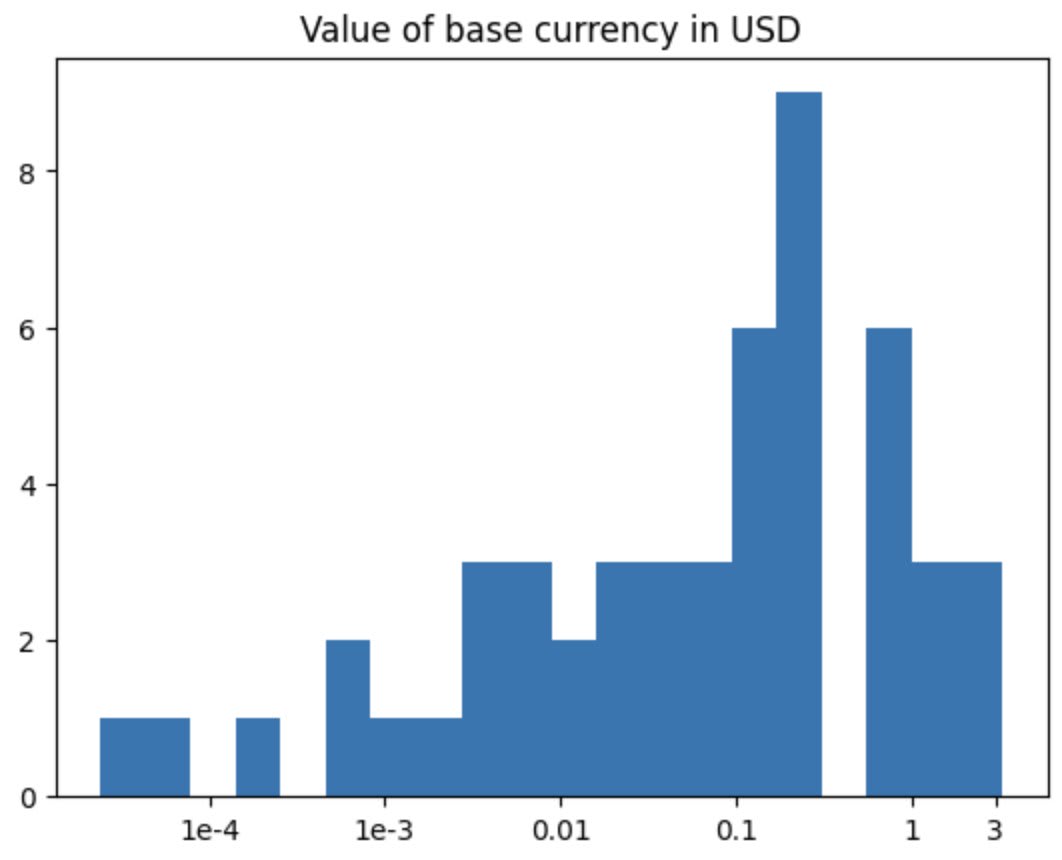

Thanks to Aryan Bhatt, Eric Neyman, and Vivek Hebbar for feedback. This post gets more math-heavy over time; we convey some intuitions and overall takeaways first, and then get more detailed. Read for as long as you're getting value out of things! TLDR How much should you optimize for a flawed measurement? If you model optimization as selecting for high values of your goal V plus an independent error X, then the answer ends up being very sensitive to the distribution of the error X: if it’s heavy-tailed you shouldn't optimize too hard, but if it’s light-tailed you can go full speed ahead. Related work Why the tails come apart by Thrasymachus discusses a sort of "weak Goodhart" effect, where extremal proxy measurements won't have extremal values of your goal (even if they're still pretty good). It implicitly looks at cases similar to a normal distribution. Scott Garrabrant's taxonomy of Goodhart's Law discusses several ways that the law can manifest. This post is about the "Regressional Goodhart" case. Scaling Laws for Reward Model Overoptimization (Gao et al., 2022) considers very similar conditioning dynamics in real-world RLHF reward models. In their Appendix A, they show a special case of this phenomenon for light-tailed error, which we'll prove a generalization of in the next post. Defining and Characterizing Reward Hacking (Skalse et al., 2022) shows that under certain conditions, leaving any terms out of a reward function makes it possible to increase expected proxy return while decreasing expected true return. How much do you believe your results? by Eric Neyman tackles very similar phenomena to the ones discussed here, particularly in section IV; in this post we're interested in characterizing that sort of behavior and when it occurs. We strongly recommend reading it first if you'd like better intuitions behind some of the math presented here - though our post was written independently, it's something of a sequel to Eric's. An Arbital page defines

As someone currently at an AI lab (though certainly disproportionately LW-leaning from within that cluster), my stance respectively would be

- "AI development should stop entirely" oh man depends exactly how you operationalize it. I'd likely push a button that magically stopped it for 10 years, maybe for 100, probably not for all time though I don't think the latter would be totally crazy. None of said buttons would be my ideal policy proposal. In all cases the decisionmaking is motivated by downstream effects on the long-run quality of the future, not on mundane benefits or company revenue or whatever.

- "risks are so severe that no level of benefit justifies them" nah, I like my

... (read 413 more words →)