You may be inspired by, or have independently invented, a certain ad for English-language courses.

My take on this stuff is that, when a person's words are ambiguous in a way that matters, then what should happen is you ask them for clarification (often by asking them to define or taboo a word), and they give it to you, and (possibly after multiple cycles of this) you end up knowing what they meant. (It's also possible that their idea was incoherent and the clarification process makes them realize this.)

What they said was an approximation to the idea in their mind. Don't concern yourself with the truth of an ambiguous statement. Concern yourself with the truth of the idea. It makes little sense to talk of the truth of statements where the last word is missing, or other errors inserted, or where important words are replaced with "thing" and "whatever"; and I would say the same about ambiguous statements in general.

If the person is unavailable and you're stuck having to make a decision based on their ambiguous words, then you make the best guess you can. As you, say, you have a probability distribution over the ideas they could have meant. Perhaps combine that with your prior probabilities of the truth values to help compute the expected value of each of your possible choices.

I claim that there's just always a distribution over meanings, and it can be sharp or fuzzy or bimodal or any sort of shape.

The issue is you cannot prove this. If you're considering any possible meaning, you will run into recursive meanings (e.g. "he wrote this") which are non-terminating. So, the truthfulness of any sentence, including your claim here is not defined.

You might try limiting the number of steps in your interpretation: only meanings that terminate to a probability within steps count; however, you still have to define or believe in the machine that runs your programs.

Now, I'm generally of the opinion that this is fine. Your brain is one such machine, and being able to assign probabilities is useful for letting your brain (and its associated genes) proliferate into the future. In fact, science is really just picking more refined machines to help us predict the future better. However, keep in mind that (1) this eventually boils down to "trust, don't verify", and (2) you've committed suicide in a number of worlds that don't operate in the way you've limited yourself. I recently had an argument with a Buddhist whose point was essentially, "that's the vast majority of worlds, so stop limiting yourself to logic and reason!"

Yeah, I definitely oversimplified somewhere. I'm definitely tripped up by "this statement is false" or statements that don't terminate. Worse, thinking in that direction, I appear to have claimed that the utterance "What color is your t-shirt" is associated with a probability of being true.

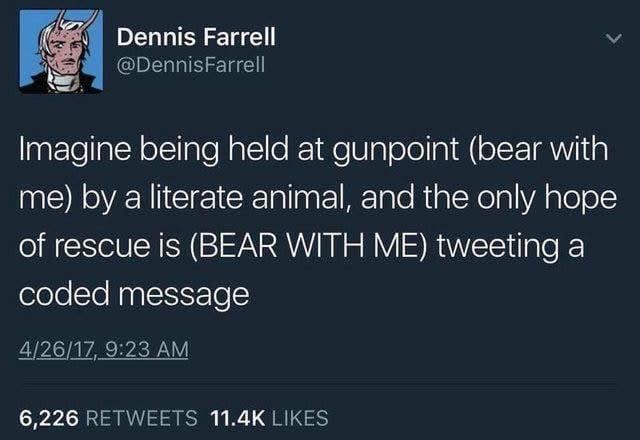

If I say "the store is 500 meters away," is this strictly true? Strictly false? Either strictly true or strictly false, with probabilies of true or false summing to one? Fuzzily true, because the store is 500.1 meters away? My thesis is that it's strictly true or strictly false, with associated probabilities. Bear with me.

The 500 meter example is pretty hard to reason about numerically. I am hopeful that I can communicate my thoughts by starting with an example that is in some sense simpler.

Is our conversational partner making a true statement or a false statement? What we're used to is starting with a prior over worlds, and then updating our belief based on observations- the man is underwater, the man is currently moving downwards. So our belief that the man is sinking should be pretty high.

However, what we are unsure of is the language of the sentence. If it's German¹, then it means¹ "the man is pensive." Then, evaluating the truth value of the sentence is going to involve a different prior- Does the man look deep in thought? He seems to have a calm expression, and is sitting cross legged, which is weak evidence. More consideration is needed.

To come out to an actual probability of the original sentence being true, we need a distribution of possible intended meanings for the sentence, and then likelyhoods of the truthfulness of each meaning. If you buy my framing of the situation, then in this case it's simply P(Sentence is English) x P(Man is sinking) + P(Sentence of is German) x P(Man is thoughtful).

In the monolingual case, it's easy to get caught up in lingual proscriptivism. If someone uses a word wrong, and their sentence is only true when it's interpreted using the incorrect definition, then a common claim is that their sentence is untrue. A classic example of this is "He's literally the best cook ever." I hope that the multilingual case illustrates that ambiguity in the meaning of phrases doesn't have to come from uncareful sentence construction or "wrong" word use.

I claim that there's just always a distribution over meanings, and it can be sharp or fuzzy or bimodal or any sort of shape. Of course, as a listener you can update this distribution based on evidence just like anything else. As a speaker, you can work to keep this distribution sharp as an aid to those you speak with, though total success is impossible.

To directly engage with the examples from the post: The statement "the store is 500 meters away" has a pretty broad and intractable distribution of meanings, but the case where

* The meaning was "The store is 500 meter away, to exact platonic accuracy"

* The store was actually a different distance, such as a value between 510.1 and 510.2 meters.

contributes only a vanishingly small amount to the odds that the statement was false.

Another case where

* The meaning was "The store is 500 meters away to a precision of 1 meter"

* The store is actually 503 meters away

contributes little to the odds that the statement was false, but contributes more if for example the speaker is holding a laser rangefinder. Odds of meanings update just like odds of world states.

For another example,

A: Is there any water in the refrigerator?

B: Yes.

A: Where? I don’t see it.

B: In the cells of the eggplant.

There is a real distribution of meanings for the statement "Yes." Our prior that A and B are effectively communicating starts low, but it is happy to rapidly increase if we recieve information like "A is deciding whether to store this calcium carbide in the refrigerator."

In my view, and assuming some sort of natural abstraction hypothesis, statements like "Every point on a sphere is equally distant from the center" are special because a significant part of their meaning is concentrated in little dirac deltas in meaning space. They are still allowed to be ambiguous or even fuzzy with some probability, but they also have a real chance of being precise.

¹ Admittedly broken German, with apologies. I possibly could come up with a better example, but I already had a great deal of time sunk into the illustration.