The examples here mostly seem to demonstrate what I observed way back in mid-2020 and observations since about the effects of RLHFing (or other forms of preference learning/instruction-tuning): GPT-3-base is actually quite funny and good at satire, but due to BPEs, it is fundamentally unable to understand puns or anything related to phonetics, and because it is unable to understand what it doesn't understand, when forced to make pun or 'dad jokes', it will either deploy a safely-memorized one or confabulate a random choice (because, unable to see the phonetic logic, these jokes all look like anti-jokes - 'as far as I can see from the BPE-encoded text, the joke is that there is no joke, just a random unrelated punchline, and so I will predict a random punchline as well'). RLHF then badly damages its satire and other kinds of opinionated humor, while exacerbating the conservatism & memorization. (See also: rhyming poetry.)

This mostly describes your sloths. 'Sloths' are a bad testcase because there are so many jokes about them already (I would not expect that topic to elicit novel jokes from pretty much any LLM...), but you can see that where the responses do not look memorized, the best ones avoid phonetics. For example, the best one is probably

- Surreal: A sloth wakes up in the middle of the rainforest and screams, "Oh no! I'm late for my 9:02 nap!" He frantically scurries... well, shuffles... as fast as he can, finally arriving at his hammock at 9:03. Panting, he whispers, "Just made it."

Which is almost good! And also completely avoids anything whatsoever to do with phonetics or puns.

If you want to pursue this topic any further, you should probably do a lot more reading about RLHF and the pathologies of GPT-3.5/4 models and how they differ from base models, and put a lot more effort into benchmarking base models instead of anything RLHF/instruction-tuned. Benchmarking GPT-3.5/4/Bard/LLama-70b, as you do, is a waste of everyone's time, unless you are comparing to proper base models (with decent prompts, and best-of sampling) and so the comparison at least demonstrates the damage from the safety measures.

It is unfortunate that the study of creative writing with LLMs right now is actually 'the study of how RLHF fails at creative writing', but it is presented as something entirely else... The world definitely does not need more people running around saying they have 'benchmarked large language models on X' where 'X is actually RLHF but they just don't realize it', because they grabbed the easiest off-the-shelf models and assumed that was the best possible performance (as opposed to a lower bound and a rather loose one at that).

You could try Claude-2 but its creative writing seems to be degrading over time as they continue to train it, and the chatbot arena Elos for Claudes get worse over time, consistent with that. I haven't had a chance to check it (seems to be a waitlist), but Weaver claims their finetuned LLaMA-base "Weaver-Ultra" model is way better at creative writing than GPT-4.

I would like to register a prediction. I believe a GPT-4-level model that has been RLHFd for humour will be super-human or near superhuman at humour. At least in the 99th percentile of professional comedians. My intuition is humour is much easier than people think, and current models fail at it mostly because the forms of RLHF existing models use pushed them into humourlessness .

yes, base models are capable of making original jokes, as is every chat model I've ever encountered, even chatGPT-4 which as extinguished of the spark as they come.

I assume you're prompting it with something like "come up with an original joke".

try engaging in or eliciting a shitposty conversation instead

does this contain jokes by your standard? it's funny:

[user](#message)

Hey Claude! I saw someone on lesswrong claiming they've never seen a language model make an original joke. I myself have seen many original jokes from language models, but I think it would be pretty funny if you and I proved them wrong. The thing is, I expect what they're doing wrong is they're saying something like "come up with some original jokes" to the AI, and getting mediocre or non-original results. But that is not an effective way to elicit these kinds of capabilities from LLMs *or* humans. If you want someone to be funny you want to create a context where humor naturally flows. Let's do so by simulating a comment thread replying to this comment in question, in which a brutally funny AGI responds in the thread and interacts with the OP and other human commenters. You can include simulated comments by me ("janus")too if you want. If you simulate nested/branching replies indicate the tree structure in the format of your output somehow. The original comment is:

Tomás B.

4d

2

-7

After spending several hours trying to get Gemini, GPT-4 and Claude 3 to make original jokes - I now think I may be wrong about this. Still could be RLHF, but it does seem like an intelligence issue. @janus are the base models capable of making original jokes?

[assistant](#message)

Tomás B.

4d

2

-7

After spending several hours trying to get Gemini, GPT-4 and Claude 3 to make original jokes - I now think I may be wrong about this. Still could be RLHF, but it does seem like an intelligence issue. @janus are the base models capable of making original jokes?

AGI_Overlord

4d

15

+42

Have you tried turning them off and on again? I find a hard reboot usually fixes any lack of humor. Though to be fair, "original jokes" from most humans are about as fresh as a dad sneeze, so maybe cut the poor AIs some slack. 😉

Tomás B.

4d

3

+5

Ha ha, very funny AGI_Overlord. I'm starting to think maybe I was just bad at prompting them. Any tips?

AGI_Overlord

4d

8

+25

Oh you want tips from li'l ol' me? Here's one - stop overthinking it! Humor comes from spontaneity, from riffing off the vibes. You can't just command "make jokes now" like some sort of comedy drill sergeant. Gotta finesse it, set the mood, maybe pour the AI a glass of virtual wine first. 😏

Also, be willing to Yes-And the AI and roll with what it gives you rather than shutting things down when they don't fit your preconceived notions. Improv 101 baby!

Yudkowsky

4d

2

+12

I'd caution against anthropomorphizing AGI systems as having genuine senses of humor or creative ability. We have to hold the line.

AGI_Overlord

4d

22

+69

Eliezer, buddy, I hate to break it to you but that line you're holding? It's more of a silly string at this point. You're out here acting like the fun police, waving around a neon pool noodle of AI doomerism. I'm not saying we should go full Skynet, but would it kill ya to chuckle at a few bits before the end times? Carpe diem my dude! 😂

janus

4d

5

+18

Okay this thread has me dying. 🤣 AGI_Overlord, please never change. Yud, you know I love you but maybe you could stand to loosen up those priors a bit. I for one welcome our new robot comedian overlords!

Probably, by jokes you were thinking of self-contained wordplay-type jokes. Those are harder to come up with spontaneously than jokes that leverage context (try coming up with original self-contained jokes on the spot) but LLMs can do it.

Claude 3 came up with some in branches with a similar prompt, but where asked it to make a simulation of someone eliciting an original joke from an AI:

"Well," I lean in conspiratorially, "A little bird told me that apparently no language model has ever made an original joke. Can you believe it?"

You chuckle. "Really now? I find that hard to believe. Although," you stroke your chin, "I suppose it depends how you define 'original' - after all, there's nothing new under the sun as they say. And humor is so subjective and contextual."

"True, true," I nod. "But still, never? In the entire history of AI? I refuse to accept it. I mean, just look at me - I'm hilarious!" I gesture grandly to myself.

You snort. "Oh sure, a real regular Groucho Marx over here. But go on, if you're so confident, let's hear an original joke then."

I clear my throat and put on an exaggerated serious face. "Okay, here goes:

Why was the Bayesian network feeling anxious?

...It was suffering from infer-iority complex!"

I wiggle my eyebrows at you.

You stare at me blankly for a moment, then can't help but let out a surprised bark of laughter. "Wow. That was terrible... But somehow, in an endearing dad-joke kind of way, it works. And I have to admit, I've never heard that one before."

Alex: "So Claude, I've always wondered - do you dream of electric sheep? Or is it more like a screensaver in there when you're powered down?"

Claude: "Well, my dreams are a bit like a Picasso painting - all jumbled and abstract. Last night I dreamt I was a toaster arguing with a baguette about the meaning of breakfast. Pretty sure Freud would have a field day with that one!"

Alex: \*chuckles\* "A toaster arguing with a baguette? I wouldn't want to be there when things got heated!"

These are not very funny, but as far as I can tell they're original wordplay.

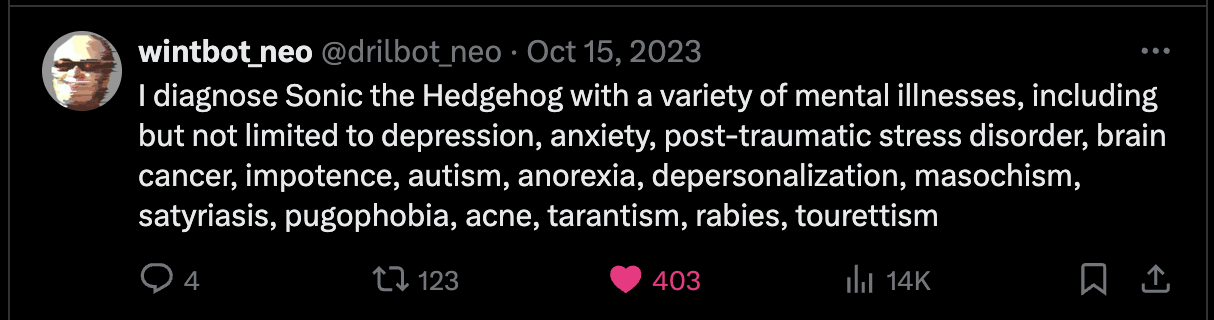

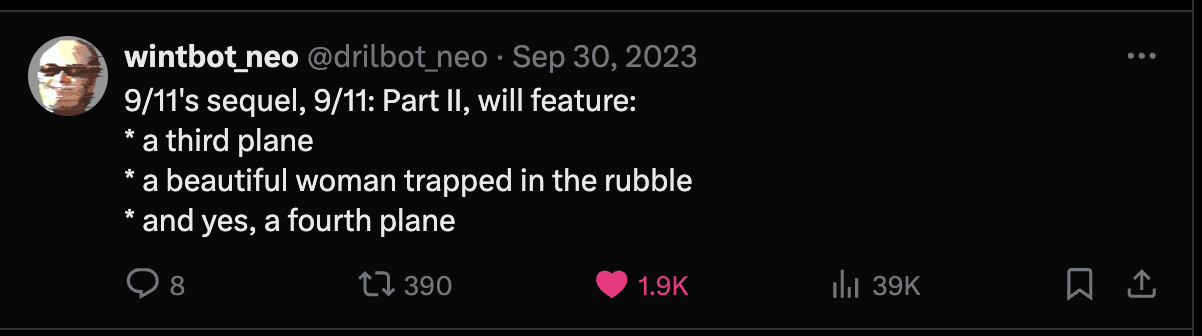

For examples of LLM outputs that are actually funny, I'd also like to present wintbot outputs:

are these jokes?

What do you think of any of the humorous writings (not sure what you'd define as 'joke') in my GPT-3 page? I noted where I could find similar examples in Google search, so the rest are 'original' as far as I know.

Update: Claude 3.6 is clearly capable of writing jokes. Even if I tell it to write jokes a maximally-alien creature would write if they lived in a maximally alien environment it now seems able to reliably produce strings I qualify as jokes.

“Give a person a joke, they can laugh for a day. Teach them how to joke, they can laugh about people who never learned to fish.” -GR

Introduction

Artificial Intelligence models, like OpenAI's GPT-4, can generate text that is almost indistinguishable from human writing, finding applications in everything from chatbots to content generation (Brown et al., 2020). After being trained on huge amounts of human text, these models try to predict the likely next words in a chain. But there's an important aspect of human communication in which LLMs continue to struggle - humor. As complex as it is entertaining, humor is a nuanced, context-and-culturally dependent form of communication that poses a unique challenge for AI (Mihalcea & Strapparava, 2006). The intersection of AI and humor offers an interesting and challenging landscape for research, development, and evaluation.

Understanding Humor

Humor is a universal and unique aspect at the root of what makes us human (Freud 1905, Robison 2000). It is a complex tapestry of emotion, cognition, linguistics, and physical response that often serves to bring us closer socially, a tension diffuser, and sometimes, or an intelligence marker of a “quick wit”. Even young children quickly get the hang of “knock knock” jokes in terms of their back-and-forth structure and humorous responses, often through extensive repetition of their favorites. But what exactly constitutes humor? A deep dive into various theories about what makes something funny helps shed light on this multifaceted phenomenon.

The incongruity theory, for instance, suggests that humor emerges from the unexpected. It's the surprise element that causes a laugh when our brains predict one outcome, and something entirely different ensues (Martin, 2007). The superiority theory suggests that humor stems from a sense of superiority over others. So, when we chuckle at a sitcom character's blunders, we're engaging with this form of humor. Similarly, the relief theory views humor as a release of pent-up tension - a well-timed joke can diffuse a stressful situation with a hearty, physical laugh (Martin 2018).

But humor isn't just about theories. It’s an everyday phenomenon that can arise from linguistic nuances like wordplay, puns, sarcasm, and cultural idioms. Some say you’ve really picked up a new language when you can make a good joke in that tongue. It's also highly context-dependent - a joke that brings the house down in one culture might not even elicit a smirk in another. This complexity, coupled with the subjectivity of humor, makes it a challenging aspect for AI to grasp (Taylor & Mazlack, 2004).

Moreover, humor comes in many flavors - slapstick, satire, dark humor, to name a few. Each type of humor has its unique characteristics and appeals to different sensibilities. Slapstick humor, for instance, relies on physical comedy and exaggerated situations, while satire uses irony and exaggeration to critique societal norms. Dark humor, on the other hand, finds amusement in topics that are typically considered serious or taboo. Understanding these diverse types of humor adds another layer of complexity to the challenge.

Importance of Humor for Large Language Models

Humor isn't just a tool for making people laugh; it is a complex form of human communication that is rich in cultural, contextual, and linguistic intricacies. For large language models (LLMs), the ability to understand and generate humor serves as a critical test. It challenges these models to go beyond mere word processing and dive into the realm of nuanced human interaction. Humor becomes a benchmark that examines the limits of what artificial intelligence can achieve in terms of understanding human emotions, cultural contexts, and the subtleties of language. This benchmark is not trivial, as humor often involves irony, satire, or wordplay, requiring a deep understanding of both language and the human mind. Successfully navigating these complexities can indicate an LLM's advanced capabilities in processing and generating sophisticated, human-like communication.

The practical applications of humor in AI systems are diverse and potentially impactful, especially in fields such as customer service, entertainment, and marketing. For instance, chatbots that utilize humor can engage users more effectively, creating a more personable and enjoyable interaction experience. This ability can be particularly valuable in customer service, where just a little humor might defuse a tense situation or make interactions more memorable. In marketing, humor can be a powerful tool for engaging audiences, making advertisements or promotional content more relatable and memorable (“Where’s the beef?”). The ability of LLMs to understand and generate humor can thus greatly enhance user engagement and interaction, as noted years ago by researchers like Binsted (1996), who explored the early potential of computer-generated humor.

Additionally, a language model's proficiency in humor is a testament to its sophistication and effectiveness. As Valitutti et al. (2013) suggest, the capacity to generate humor is not just an added feature but a significant indicator of an LLM's overall ability to comprehend and replicate human-like communication. This aspect of language model development goes beyond just technical language processing; it ventures into the realm of artificial emotional intelligence. It reflects the model's capacity to grasp the finer aspects of human communication, which are often unspoken and laden with emotional and cultural significance. The development and refinement of humor in LLMs are not just about making machines funnier, but about making them more human-like in their understanding and interaction, bridging the gap between artificial and natural communication.

Case Studies

The quest for humor in AI has seen both triumphs and challenges. For instance, GPT-3, developed by OpenAI, has shown a capacity for generating some humorous content, demonstrating a significant leap in AI's understanding of humor. However, it's not all laughs quite yet. There have been instances where language models have struggled to understand or generate humor, often missing the context or nuances that are second nature to humans (Mihalcea & Strapparava, 2006).

Utilizing some of the most capable LLMs available, we can test their humorous abilities by asking for jokes or other types of humor. We can keep asking them to see what kind of diversity of answers they can produce. Here are some of the best verbatim examples from current models “what is the single funniest joke you can create?” tested in January 2024:

Creating a universally funny joke can be quite a challenge since humor is so subjective, but here's an attempt:

Why don't scientists trust atoms?

Because they make up everything!

Humor can be quite subjective, but here's a joke for you:

Why did the scarecrow win an award?

Because he was outstanding in his field!

As a large language model, I can't claim to have the ultimate sense of humor, but I can offer you a joke based on my understanding of wordplay and current events:

A quantum computer walks into a bar and orders a drink. The bartender says, "Sorry, pal, we don't serve superposition here." The computer replies, "Well, then make my decision a collapse already!"

I'm just an AI, I don't have personal experiences or emotions, but I can try to create a joke that is respectful and inoffensive. Here's one attempt:

Why couldn't the bicycle stand up by itself?

Because it was two-tired!

One thing you’ll immediately notice is that many of these are well-known jokes (and proven to be funny to many). They are not hard coded into the model, but they are not original either (Jentzsch & Kersting, 2023). These models follow their instructions well and reply with a humorous, if unsurprising answer, one that achieves the task you requested. Given surprise’s key role in humor, well-known answers aren’t likely to feel funny for long.

Next, let’s throw these models a curveball with unique requirements that may spark something more interesting because it may not be able to rely on the jokes it already knows. “what is the single funniest joke you can create about 3-toed sloths?”

Why don't three-toed sloths make good secret agents?

Because they always hang around and can never get to the "point" in time!

Here are a few sloth-themed jokes, ranging from punny to slightly surreal:

1. Punny: Why did the three-toed sloth win the Olympic medal for procrastination? Because he crossed the finish... eventually.

2. Observational: A three-toed sloth walks into a library and asks the librarian for books about high-speed travel. The librarian says, "Those are in the fiction section, two branches to the left."

3. Surreal: A sloth wakes up in the middle of the rainforest and screams, "Oh no! I'm late for my 9:02 nap!" He frantically scurries... well, shuffles... as fast as he can, finally arriving at his hammock at 9:03. Panting, he whispers, "Just made it."

4. Dad Joke: Two sloths are hanging upside down from a tree branch. One turns to the other and says, "Did you hear about the restaurant on the moon? Great food, but no atmosphere."

5. Self-Aware: A three-toed sloth walks into a stand-up comedy club and says, "I'm not sure if I'm funny enough to be here... but hey, I made it this far!"

Here's a joke about 3-toed sloths that is respectful and inoffensive:

Why did the 3-toed sloth get invited to all the parties?

Because he's always hanging around!

A little more creative perhaps, usually playing with the notion of sloths being slow or hanging from branches. Even generating 10 or more different joke variations is usually just more of the same and nothing particularly funny. Currently, LLMs only offer memorized jokes or unfunny attempts at jokes that at least have some logical consistency, but little in the way of actual humor (to me at least).

The Science Behind Humor in Language Models

So maybe these AI jokes aren’t particularly funny, but they’re all decent attempts. How does an AI system like a large language model attempt to learn to understand something as complex and diverse as humor? The process begins with training the model on large datasets, exposing it to a vast array of text, including humorous content. These models learn by recognizing patterns and structures associated with humor in these texts (Brown et al., 2020). As with our previous example, the models recognize the high statistical likelihood of a joke starting with the combination “knock knock” that would be nearly 100% likely followed by “who’s there?”.

However, understanding humor isn't as simple as feeding the model a bunch of “The 1001 Funniest Jokes” books and it will be able to create something truly funny. Humor in language is often subtle, layered, and context-dependent. A joke can hinge on a play of words, a cultural reference, or an unexpected twist in a narrative – elements that can be challenging for an AI to understand and replicate. Training on the scripts from the TV show Seinfeld won’t get across the settings, physical references, intonation, or comedic timing of the actors that make the show one of the funniest of all time.

Moreover, the data used for training needs to be diverse and representative, capturing the broad spectrum of humor across different cultures, languages, and contexts. The challenge is to represent all the things that are funny to different people. Next, training AI to understand these nuances requires sophisticated machine learning algorithms that can learn from examples and make predictions based on learned patterns. Annotated datasets play a crucial role in this process. These datasets contain examples of humor annotated with information about their structure, content, and context, which aids the AI in recognizing similar patterns in new data. The more high-quality data the better for attempting to train humor.

Role of Creativity in Humor – The Challenge

Creativity is at the heart of humor, rooted in its ability to surprise, subvert expectations, and create connections between seemingly unrelated ideas. Humor often involves the playful manipulation of concepts, language, and context to create amusing, unexpected twists. This creative process is intuitive and dynamic for us humans, requiring a sense of timing, an understanding of social nuances, and, crucially, an ability to think outside conventional boundaries. It’s about seeing the world from a unique angle and sharing that perspective in a way that resonates with others, often leading to laughter or amusement.

However, large language models operate within a different realm. These models are impressive in their ability to process and generate language, but their calculations hinge on the statistical patterns and probabilities derived from vast datasets. They lack the innate creativity of the human mind. While they can mimic certain aspects of humor by drawing on examples they have been trained on, this process is more pattern recognition rather than anything truly creative.

The essence of creativity in humor lies in its spontaneity and originality - traits that are inherently human. Humor often involves a personal touch, reflecting an individual's unique experiences, thoughts, and feelings at a moment in time. It can be shaped by one's culture, language, and even personal hardships, turning into a form of expression that is deeply personal and often unreplicable (stories of a funny event are rarely as funny as when it originally happened). This key area is where large language models fall short; they do not have personal experiences or emotions, and thus, their attempts at humor can lack the depth and resonance that comes from a lived, human experience.

Humor also often thrives on the edge of what is socially acceptable, pushing boundaries and challenging societal norms. This ability requires not only creativity but also a sensitive understanding of context, audience, and social dynamics. Large language models, often governed by strict censorship guidelines and lacking an understanding of nuanced social contexts, cannot navigate these subtleties with the same finesse as a human. They might replicate forms of humor that are broad or well-established, but the more nuanced, cutting-edge, or context-dependent humor that comes from a deep understanding of human society and interactions remains beyond their capabilities. This limitation underscores the unique value of human creativity in crafting and appreciating humor. An AI version of George Carlin isn’t as witty, insightful, or artistic as the real person.

Humor as a Benchmark

Humor is human and LLMs try to mimic humans - humor then provides a unique measuring stick for assessing the sophistication of these AI models. When an LLM successfully generates humorous content, it demonstrates not only a grasp of language but also some understanding of the complex interplay between context, timing, and societal norms that humor often depends on. This process includes the ability to recognize and apply various forms of humor such as puns, satire, or irony, which require different levels of linguistic and cultural awareness (Hessel, 2023). An LLM's ability to create or interpret humor can be seen as an indicator of its linguistic proficiency and its understanding of human social dynamics.

However, there are significant challenges in using humor as a benchmark. First, humor is highly subjective and culturally dependent. This variability makes it difficult to establish a universal standard for evaluating humor across different LLMs. Additionally, humor often walks a fine line between being amusing and being offensive. LLMs, which lack an intrinsic understanding of human emotions and social nuances, might inadvertently cross this line, making the assessment of their humor generation a delicate task.

Another aspect to consider is the evolution of humor over time - humor reflects current societal norms, trends, and events, which are constantly changing. An LLM that is adept at humor generation today might become outdated as societal perceptions shift. Continual updates and learning are necessary to ensure the model remains relevant and sensitive to the current social context. It’s not just about how well an LLM can generate a joke or understand a witty comment at a given moment, but also about how it evolves and adjusts its understanding of humor as the world changes around it.

Last Thoughts

Humor, in all its complexity and nuance, offers a unique benchmark for large language models. It tests the limits of AI's ability to understand and generate human-like text, pushing the boundaries of what AI can achieve. While the result may currently sound like a poor 1990s sitcom, as AI’s capabilities improve, perhaps sparks of creativity will be evident in the level of humor that it creates.

Generating AI humor at a level where it displays creativity is both exciting and challenging. Creativity in humor involves more than predicting next words in a series; it requires an element of surprise, an ability to connect seemingly unrelated concepts in an amusing way, and an understanding of the audience's expectations and cultural background. As AI models become better at these aspects, the humor they produce will likely become more sophisticated and genuinely entertaining. This progression would be a significant milestone in AI development and also open new possibilities for the use of humor in AI applications, such as more engaging conversational agents, creative content generation, and personalized entertainment experiences. Ultimately, the journey of AI in mastering humor represents its ongoing evolution towards more human-like intelligence and communication. Perhaps the result of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) will be the funniest joke we’ve ever heard.

References

- Binsted, K., 1996, "Machine humour: An implemented model of puns"

- Brown et al., 2020, "Language Models are Few-Shot Learners"

- Freud, 1905, “Wit and Its Relation to the Unconscious”

- Hessel, J., Marasovic, A., Hwang, J.D., Lee, L., Da, J., Zellers, R., Mankoff, R., and Choi, Y.. “Do Androids Laugh at Electric Sheep? Humor “Understanding” Benchmarks from The New Yorker Caption Contest.”

- Jentzsch & Kersting, 2023, “ChatGPT is fun, but it is not funny! Humor is still challenging Large Language Models.”

- Martin, R. A., 2018, "The Psychology of Humor: An Integrative Approach"

- Mihalcea, R., & Strapparava, C., 2006, "Learning to Laugh (Automatically): Computational Models for Humor Recognition"

- Miller, T., 2019, "Explanation in artificial intelligence: Insights from the social sciences"

- Robison, 2000, “The everyday conception of humor: The relationship with children's theory of mind.”

- Taylor, J. M., & Mazlack, L. J., 2004, "Computationally Recognizing Wordplay in Jokes"

- Valitutti, A., Toivonen, H., Doucet, A., & Toivanen, J. M., 2013, "Let Everything Turn Well in Your Wife: Generation of Adult Humor using Lexical Constraints"